New Exhibit – Pediatric Developments

The Aufses Archives staff has installed our latest exhibit in the lobby of the Annenberg Building. This season’s exhibit, Pediatric Developments, showcases the evolution of children’s medical care over the last two centuries in the histories of our Health System’s hospitals. This blog post focuses only on the Mount Sinai Hospital histories presented in the exhibit.

While the prevailing narrative is that the field of pediatrics slowly grew into a medical specialty in the early 20th century, the care provided at our hospitals was ahead of the curve with early establishment of wards and services tailored specifically to children. Our doctors and health care workers sought to treat not only the serious and often fatal childhood ailments (many now preventable through routine vaccination), but worked to improve living conditions, nutrition, education, psychology, and convalescence while contributing to the development of Pediatrics as a specialty.

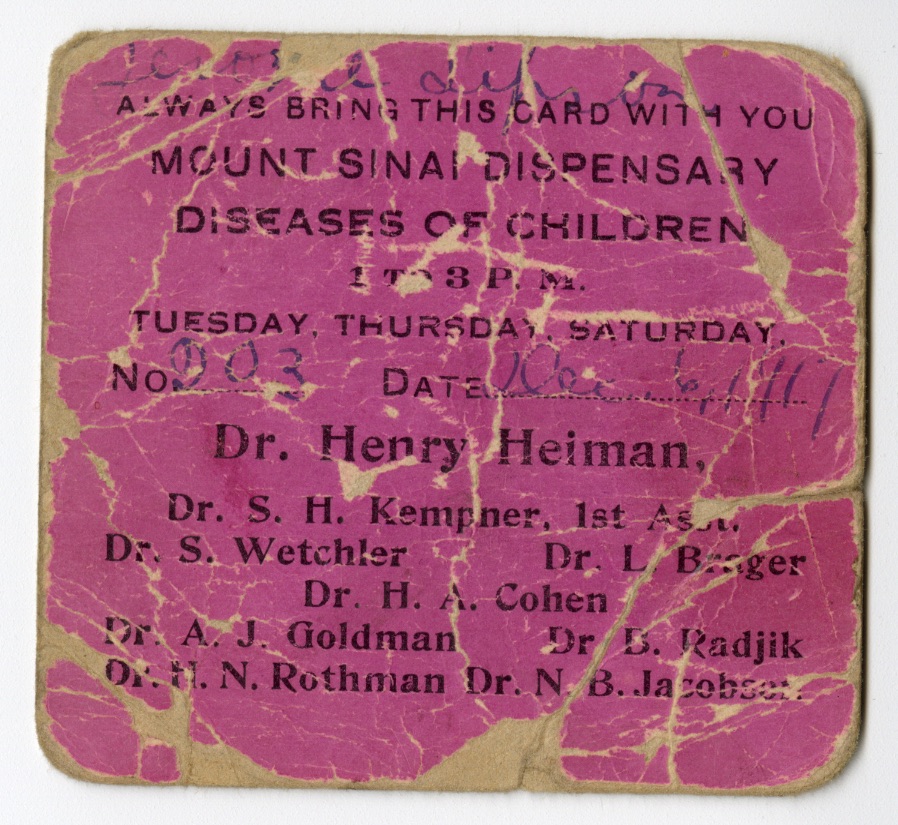

150 years ago, Mount Sinai Hospital established an “Outdoor Dispensary” for patients who did not need to be admitted overnight. This was due to the advocacy of Dr. Abraham Jacobi, the progenitor of Pediatrics, who was a foundational force from his appointment in 1860 to the Jews’ Hospital as Attending Physician, until his death in 1919. Children had always been admitted to the Hospital, but they were placed on adult wards.

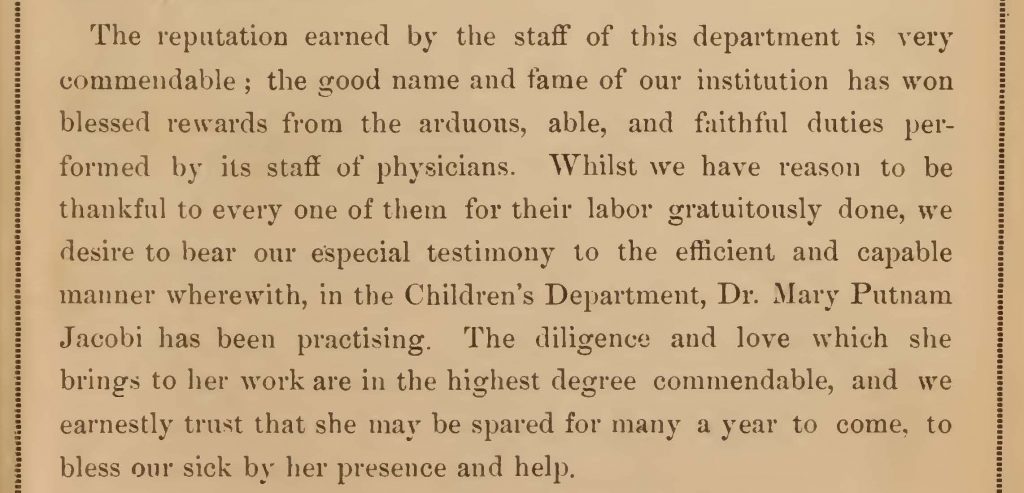

In 1875, a Children’s Department in the Mount Sinai Hospital Dispensary was organized with Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi serving as head of the service. Together, the Drs. Jacobi had published Infant Diet in 1874 and married several months later. Because the facilities for children in the Dispensary were not sufficient to care for the great number referred to the Hospital, an inpatient Pediatric ward was opened in 1879 with Dr. Abraham Jacobi as Chief. Remarkably this was the first inpatient pediatric department in New York City.

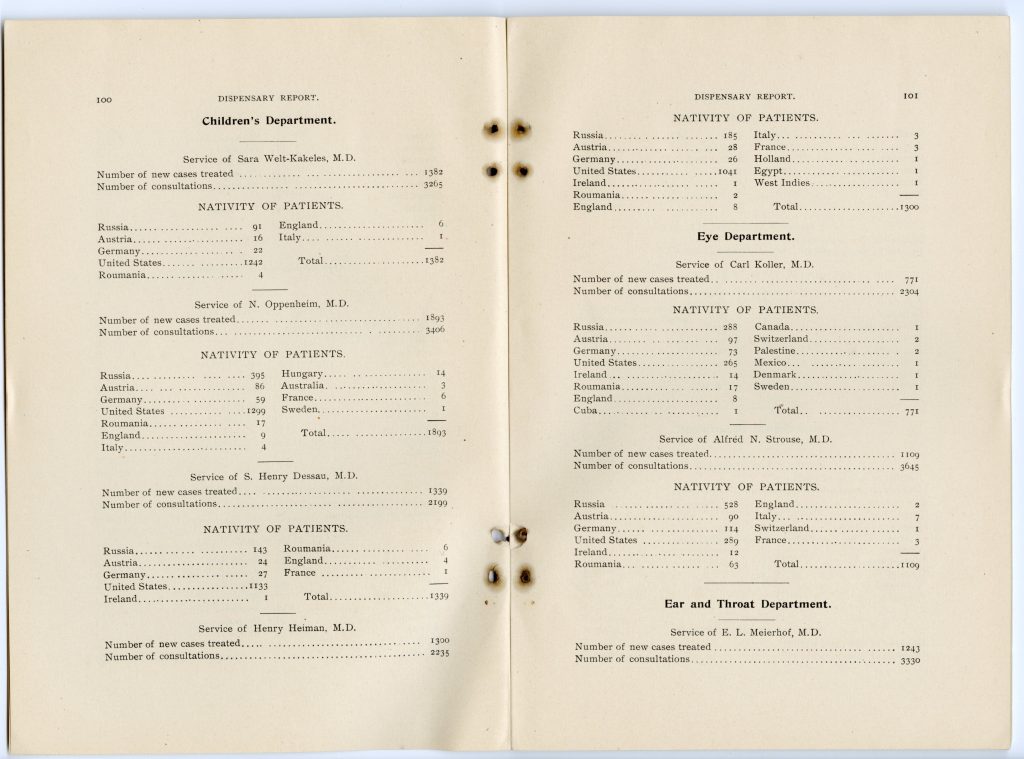

135 years ago in 1887, Dr. Sara Welt was the first woman to be appointed an Adjunct Pediatrician. She spent her whole career at Mount Sinai Hospital and remained closely affiliated until her death in 1943, at which time she bequeathed nearly $1 million to support the Pediatric Clinic and establish the Sara Welt Fellowship in Research Medicine, a loan fund for young physicians who needed financial assistance.

Dr. Ira Wile, who joined the Mount Sinai Hospital Pediatric staff in 1904, developed an early interest in child psychiatry, behavioral and social problems of children, and child education. In 1919, he opened the first child guidance clinic in the United States. Named the Children’s Health Class, it became the first vehicle through which preventive medicine was integrated on an equal footing with the rest of the pediatric activities of the Hospital. He stated, prophetically, that “the attention of the clinic is directed chiefly to the periodic examination of children between infancy and school age. This is a period during which the health of poorer children is commonly neglected, and when physical and psychological mismanagement may readily implant the seeds of disease against which the Department of Health and other agencies subsequently struggle in vain.”

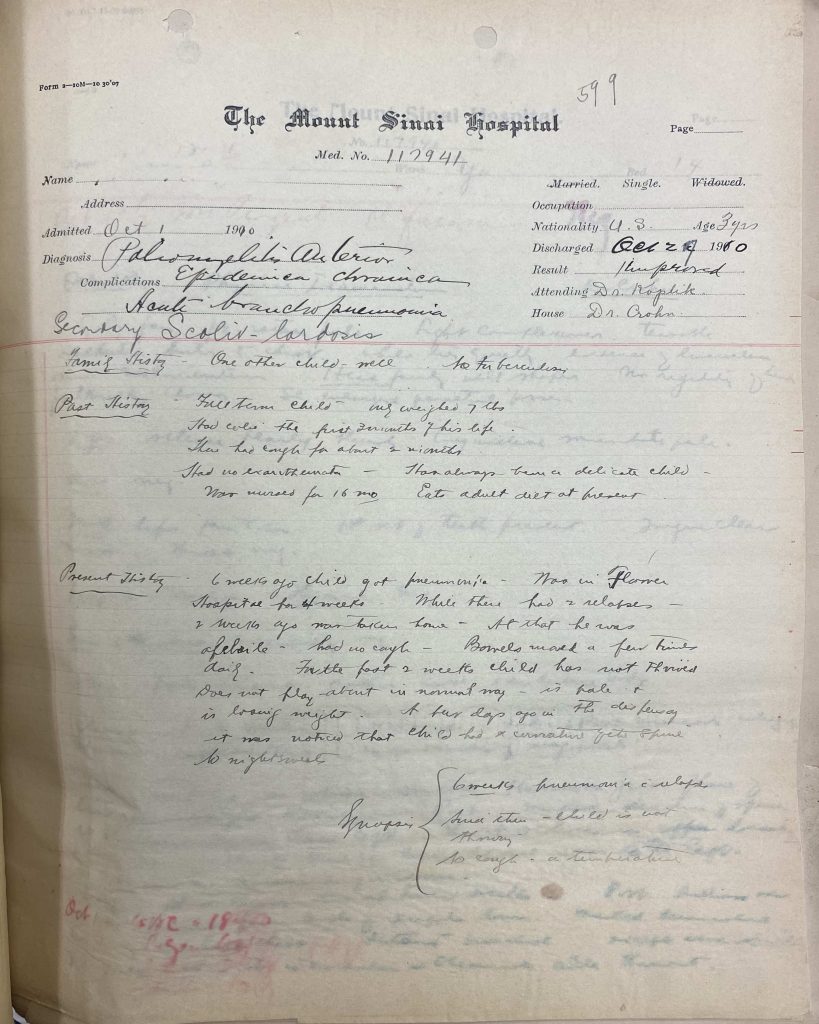

In 1889, Dr. Henry Koplik founded the first station for the distribution of sterilized milk in New York City at the Good Samaritan Dispensary in lower Manhattan. In 1896, Koplik described the diagnostic spots of measles in the buccal mucous membranes, which to this day bear the name “Koplik spots.” He was one of the first pediatricians to take an interest in bacteriology and conducted fundamental studies on diphtheria and pertussis organisms. In 1902, he assumed the coveted role of Attending Pediatrician at Mount Sinai Hospital. For the next 25 years, he served on the Medical Board, taught at the School of Nursing, and was a consulting expert on Pediatrics.

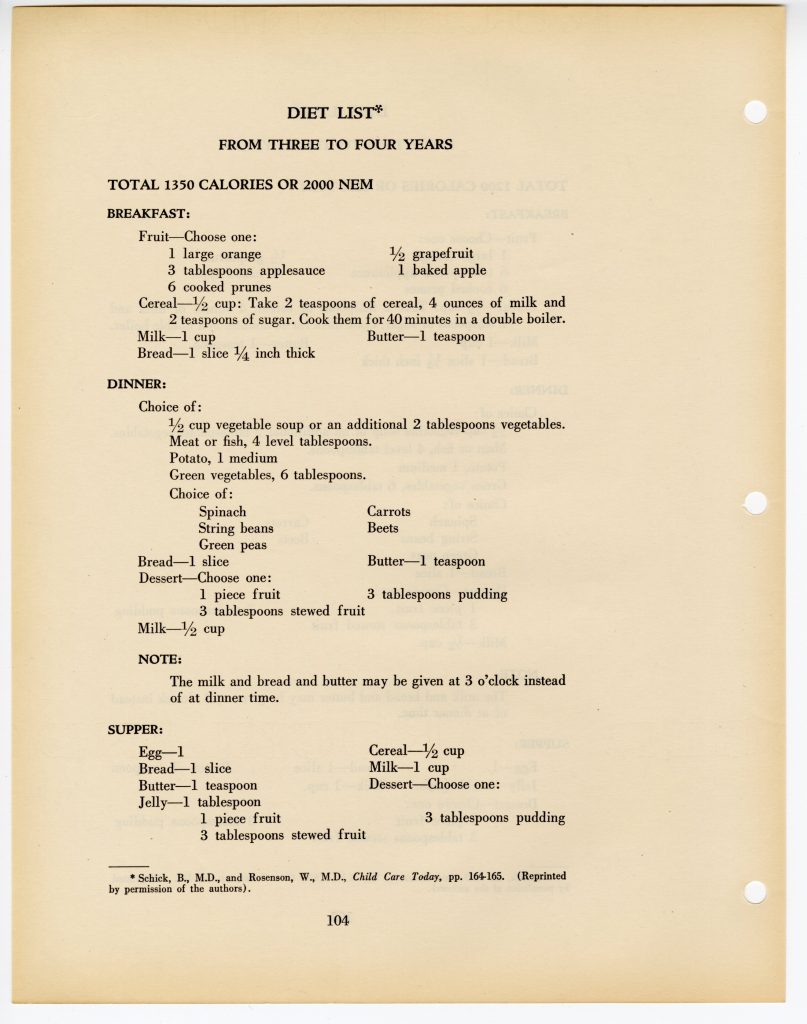

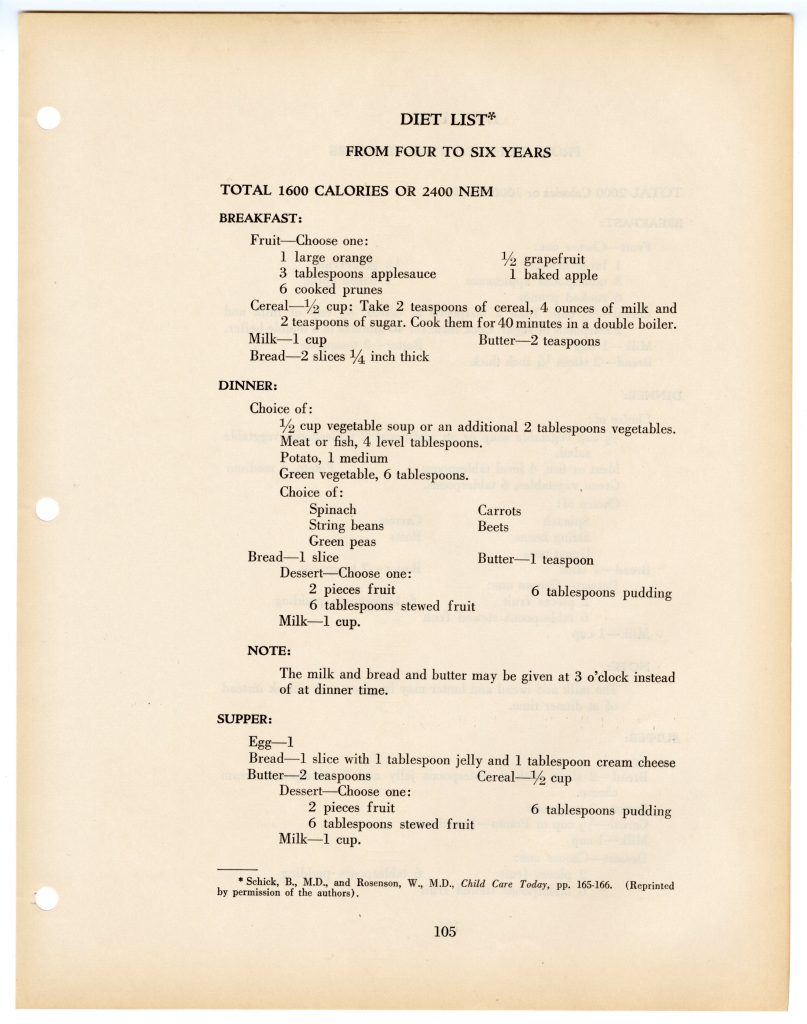

In 1923, Mount Sinai Hospital invited Dr. Béla Schick, a pediatrician of renown in Europe, to come to Mount Sinai and serve as Pediatrician to the Hospital. In collaboration with Dr. Clemens von Pirquet, Schick had already conducted his groundbreaking work on antigen/antibody reactions, which laid the foundation for immunity and hypersensitivity. They introduced the term “allergy.” Schick also had done his pioneering studies on diphtheria, developing a skin test with toxin from diphtheria organisms. The “Schick Test” was the first of many skin tests used to determine whether a child was immune or susceptible. In his later years Dr. Schick also focused on infant and child nutrition, as evidenced by this Diet Manual from 1939.

Dr. Jean Pakter, pictured, spent five years at Mount Sinai Hospital, finishing her residency in 1939. An advocate for maternal and child health, she devoted her life to serving not only the City of New York, as Director of the Department of Health’s Bureau of Maternity Services and Family Planning from 1960 to 1982, but the nation as well. Her discipline for gathering and sharing statistics led to many noteworthy studies on prematurity, maternal and fetal mortality, abortion, sudden infant death syndrome, and promotion of breast feeding. Her Mount Sinai training of using scientific study and clinical expertise as a means of enacting social change led deservedly to numerous honors, awards, and citations, most notably in the Roe v. Wade decision.

Polio, measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis… many of the serious and often fatal childhood ailments that were common in the nascent years of the field of Pediatrics are today prophylactically addressed through routine childhood vaccinations. One of the most notable vaccines was for polio, released in 1955. Developed by Dr. Jonas Salk, who interned at Mount Sinai Hospital from 1940-1942, the evaluation of the vaccine was conducted by pioneering Black scientists, Russell W. Brown and James H.M. Henderson at Tuskegee Institute, by creating the first HeLa cell factory.

This casebook entry from 1910 shows a child being treated for poliomyelitis, bronchopneumonia, and scoliosis. While this child was discharged with their conditions improved, the case book is filled with patients seen by Dr. Henry Koplik and Dr. Burrill Crohn (listed as Attending and House Staff above) who succumbed to illnesses that are preventable today.

We welcome you to visit the exhibit in person to read about the histories of Mount Sinai Morningside, Mount Sinai West, and Mount Sinai Beth Israel.

Authored by J.E. Molly Seegers

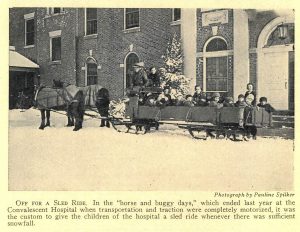

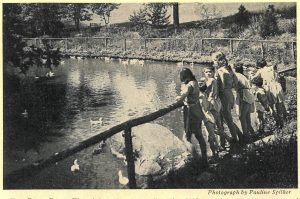

Since 1919, St. Luke’s had been looking for just such a donation to relieve the Hospital of the many patients that were recuperating or rehabilitating at the Hospital, taking up beds needed for more acute care cases. In fact, from the early years of the Hospital, the Managers frequently sought convalescent space for those patients who no longer needed acute care, but still needed to recuperate or rehabilitate under medical and, at times, surgical supervision. If possible, the ideal spot would be within a twenty-five mile radius of the city, in a rural area where patients, especially children, could benefit from space, sunshine, and fresh air. Most of the early locations, on Long Island and in New Jersey, were second homes, loaned to St. Luke’s for a period of time, or were independent convalescent hospitals that took in St. Luke’s patients. For a while, St. Luke’s had an exclusive relationship for convalescent care with St. Johnland Hospital, in King’s Park, Long Island, but only for about 30 children. Over time, the Board of Managers realized they need a larger and more permanent facility. Indeed, soon after the new building was opened, plans for its expansion began, so great was the demand.

Since 1919, St. Luke’s had been looking for just such a donation to relieve the Hospital of the many patients that were recuperating or rehabilitating at the Hospital, taking up beds needed for more acute care cases. In fact, from the early years of the Hospital, the Managers frequently sought convalescent space for those patients who no longer needed acute care, but still needed to recuperate or rehabilitate under medical and, at times, surgical supervision. If possible, the ideal spot would be within a twenty-five mile radius of the city, in a rural area where patients, especially children, could benefit from space, sunshine, and fresh air. Most of the early locations, on Long Island and in New Jersey, were second homes, loaned to St. Luke’s for a period of time, or were independent convalescent hospitals that took in St. Luke’s patients. For a while, St. Luke’s had an exclusive relationship for convalescent care with St. Johnland Hospital, in King’s Park, Long Island, but only for about 30 children. Over time, the Board of Managers realized they need a larger and more permanent facility. Indeed, soon after the new building was opened, plans for its expansion began, so great was the demand.

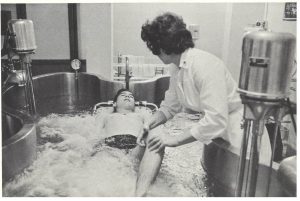

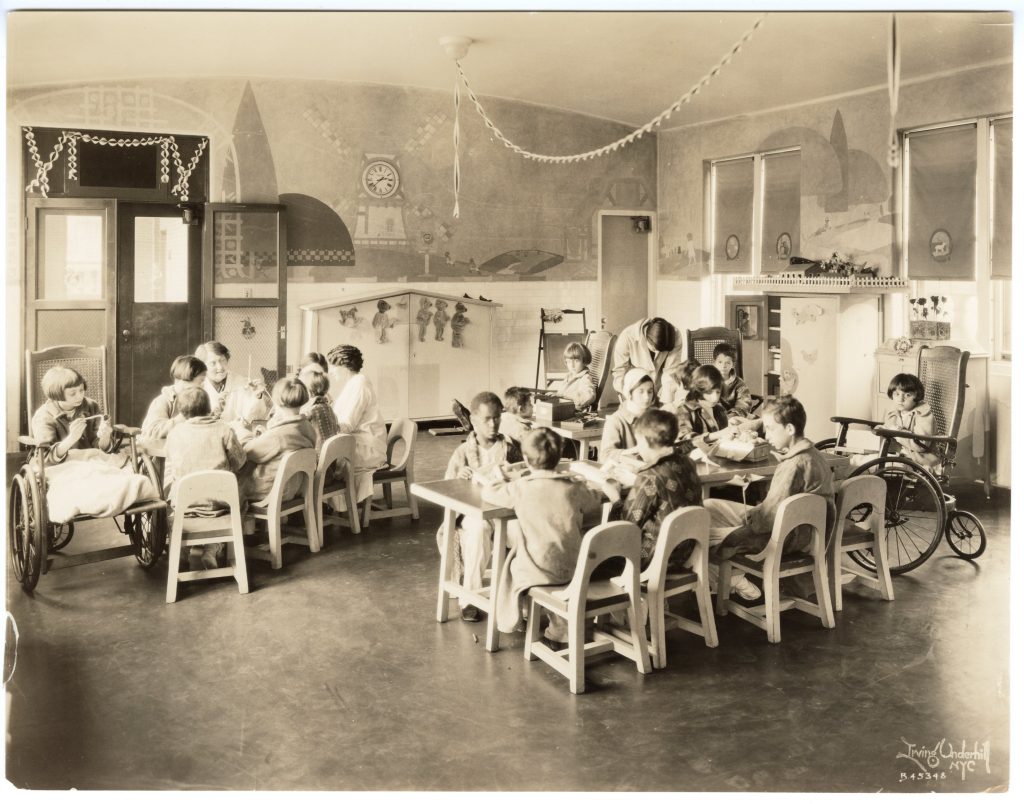

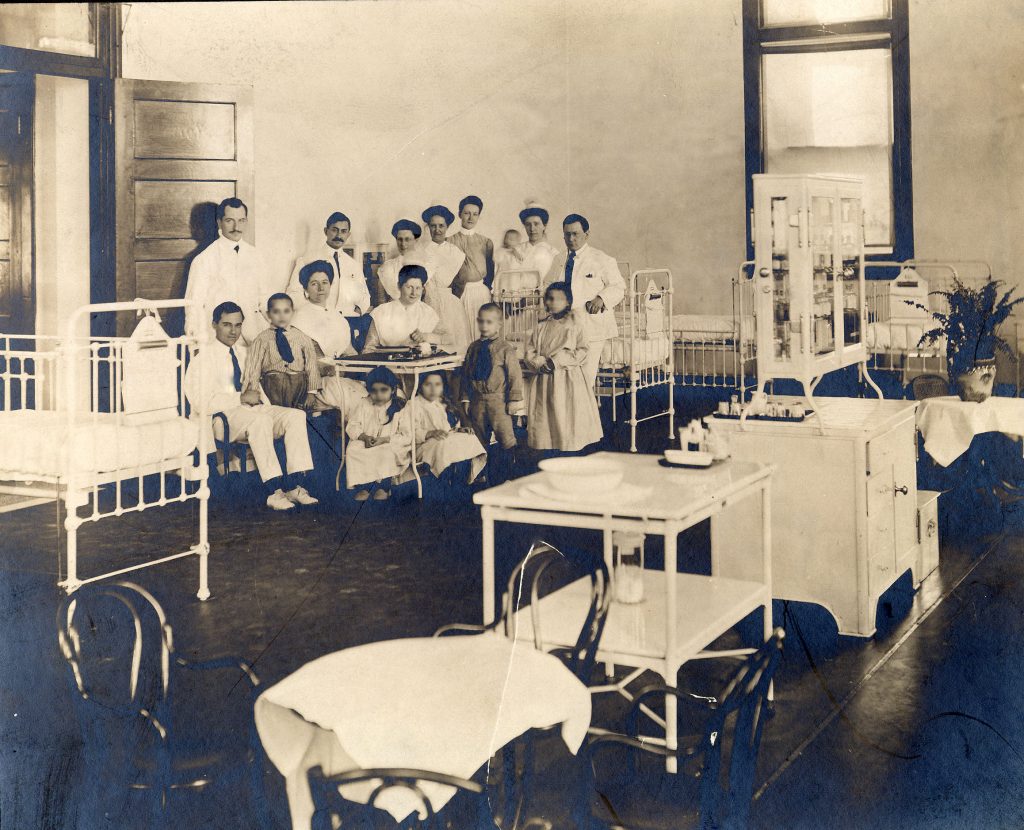

Attending and Consulting staff of physicians and a Resident physician living on-site, other specialists included physical therapists, social workers, occupational therapists, dietitians, nurses, recreation leaders, laboratory technologist, and pediatrics specialists.

Attending and Consulting staff of physicians and a Resident physician living on-site, other specialists included physical therapists, social workers, occupational therapists, dietitians, nurses, recreation leaders, laboratory technologist, and pediatrics specialists.