Oct 14, 2019

Thirty-five years ago, on October 3, 1984, the Beth Israel Hospital School of Nursing was renamed and dedicated as the Phillips Beth Israel School of Nursing, in honor of Seymour Phillips. Mr. Phillips (1903-1987) served as chairman of the School of Nursing Board for almost 40 years. He watched over the School through a myriad of changes, in nursing, in Beth Israel, and the world. He also was a tremendous supporter of the Hospital itself, in particular supporting cardiac care and surgery. Mr. Phillips was the grandson of the founder of Phillips-Van Heusen Corporation and actively worked at the company from 1924-1967.

Seymour Phillips greeting members of the Beth Israel Class of 1968

Serving Beth Israel was a Phillips family tradition that stretched before Seymour Phillips and after him as well. Their name continues to be associated through the Phillips Ambulatory Care Center, the Phillips Family Practice, the Phillips Health Sciences Library and, of course, the Phillips Beth Israel School of Nursing.

As noted in the centennial history of the School of Nursing:

At every school of nursing graduation, Seymour Phillips stood at the podium and gave a rousing, inspiring speech for the graduates. He would turn his back to the audience and directly address the new nurses seated on the stage, as if no one else was in the auditorium. The students did not need to be told how much Phillips cared for them. His actions spoke louder than his eloquent words.

When Seymour Phillips died on 1987, Rose Muscatine Hauer, [then] Dean Emeritus…was one of the speakers at the service at Temple Emmanuel…. Hauer stepped to the podium to address the audience. As she looked up to speak, 200 nursing students in uniform – their starched white caps at attention – rose from their seats to honor their dear friend and long-time patron.

Apr 30, 2019

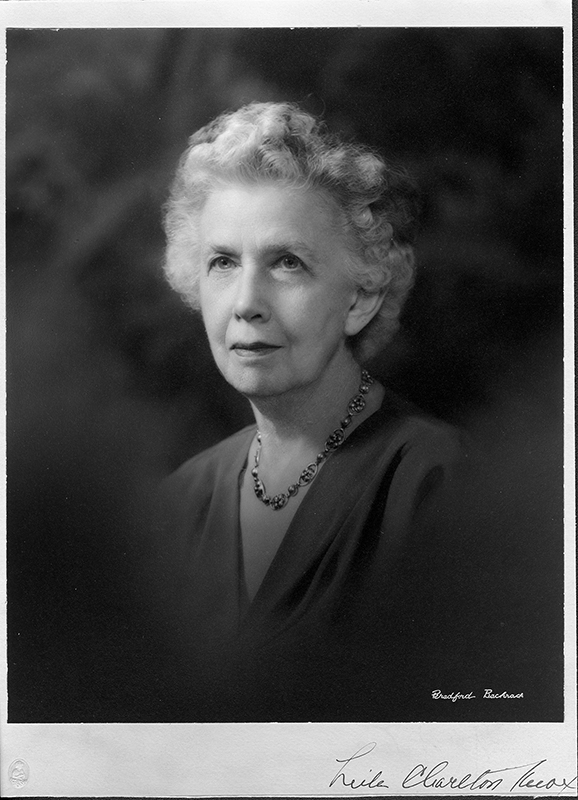

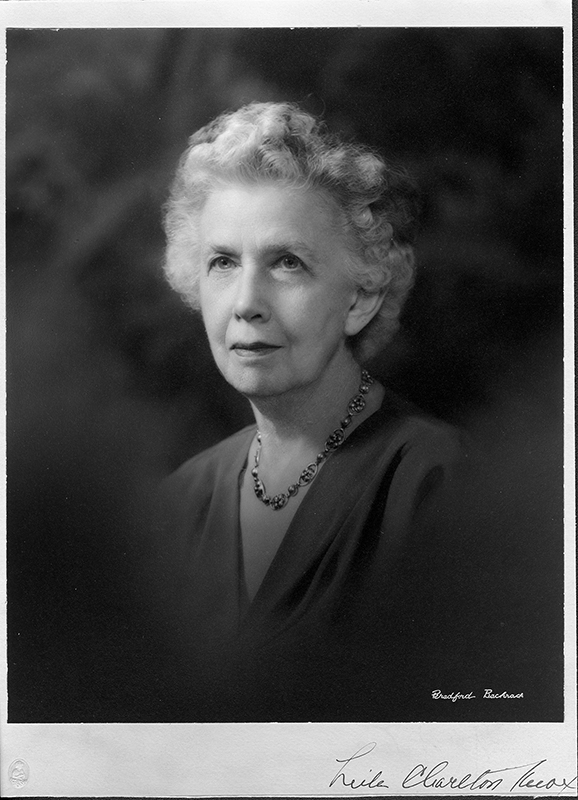

March is Woman’s History month and there are many notable women from within the MSSL fold to honor, but Dr. Leila C. Knox is the first notable woman I would like to highlight for Women’s History Month. Dr. Knox was the first woman to be hired as an Attending Physician on any level at St. Luke’s Hospital. Leila Knox, BA started at St. Luke’s in 1913 as an assistant and bacteriologist to Resident Pathologist Dr. J. Gardiner Hopkins. At that time, it wasn’t uncommon for educated women to work in the Pathology Labs. But long-time Director of Pathology, Dr. Francis C. Wood knew Knox wanted more out of her work and encouraged her to attend medical school. She enrolled in Cornell University Medical College. She became the Resident Pathologist at St. Luke’s in 1917, and in 1918 she added ‘MD’ to that title. Working together, she and Dr. Wood developed a surgical pathology lab of importance and value, and one which was notable in its field. She was appointed Assistant Attending Physician in 1923, a title which was unique at that time. Knox wasn’t restricted to laboratory work, but trained technicians and members of the House Staff, conducted autopsies, and made rounds as an Attending to observe patients. She published many papers generated by her efforts both as an Attending and a Pathologist, and was Assistant Editor of the American Journal of Cancer from 1930-1938, writing abstracts and original articles for the publication. She was recognized abroad and at home for her work as a tissue diagnostician. She retired in 1948 after thirty years of service, holding the title of Pathologist, Director of Laboratories and Associate Attending Physician.

March is Woman’s History month and there are many notable women from within the MSSL fold to honor, but Dr. Leila C. Knox is the first notable woman I would like to highlight for Women’s History Month. Dr. Knox was the first woman to be hired as an Attending Physician on any level at St. Luke’s Hospital. Leila Knox, BA started at St. Luke’s in 1913 as an assistant and bacteriologist to Resident Pathologist Dr. J. Gardiner Hopkins. At that time, it wasn’t uncommon for educated women to work in the Pathology Labs. But long-time Director of Pathology, Dr. Francis C. Wood knew Knox wanted more out of her work and encouraged her to attend medical school. She enrolled in Cornell University Medical College. She became the Resident Pathologist at St. Luke’s in 1917, and in 1918 she added ‘MD’ to that title. Working together, she and Dr. Wood developed a surgical pathology lab of importance and value, and one which was notable in its field. She was appointed Assistant Attending Physician in 1923, a title which was unique at that time. Knox wasn’t restricted to laboratory work, but trained technicians and members of the House Staff, conducted autopsies, and made rounds as an Attending to observe patients. She published many papers generated by her efforts both as an Attending and a Pathologist, and was Assistant Editor of the American Journal of Cancer from 1930-1938, writing abstracts and original articles for the publication. She was recognized abroad and at home for her work as a tissue diagnostician. She retired in 1948 after thirty years of service, holding the title of Pathologist, Director of Laboratories and Associate Attending Physician.

Apr 30, 2019

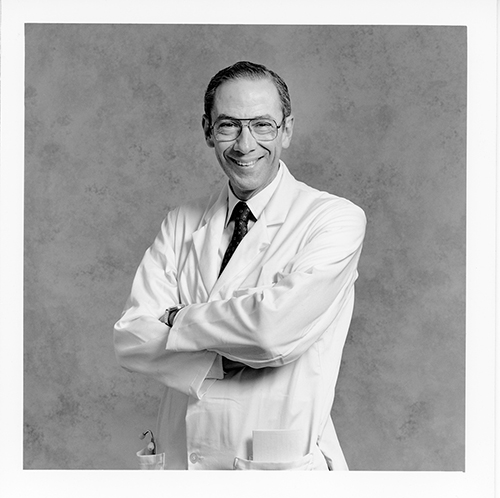

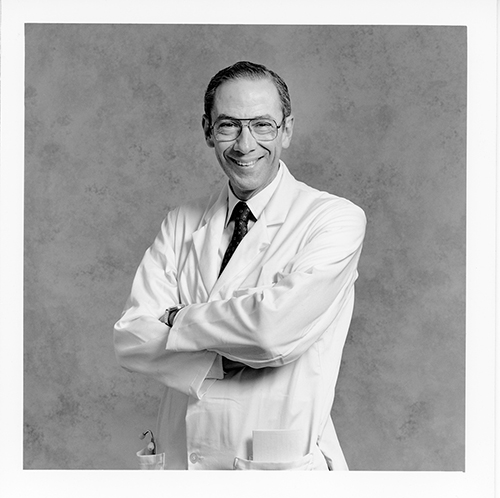

It is with great sadness that we share news of the passing of our dear friend and supporter Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD (1926-2019), one of the Mount Sinai Health System’s most respected physicians and Chairman Emeritus of The Ruth J. & Maxwell Hauser and Harriet & Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Department of Surgery at The Mount Sinai Hospital, and Professor in Surgery as well as the Department of Population Health Science and Policy.

Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD, 1926-2019

An innovative leader who served as Chair of the Department of Surgery from 1974-1996, Dr. Aufses ushered in Mount Sinai’s adoption of laparoscopic surgery and oversaw the expansion of ambulatory surgery and the hospital’s transplant program. He organized the surgical team that performed the first liver transplant in New York State in 1988.

Within Mount Sinai, Dr. Aufses served as a mentor to many residents and fellows and helped to break down barriers for women and minority surgeons. Over the years, he received many Excellence in Teaching awards from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, as well as institutional honors, including the Alumni Association’s Jacobi Medallion, and the Alexander Richman Award for Humanism in Medicine. He was the holder of Mount Sinai’s Gold Headed Cane from 1982 to 1997. On 17 occasions, medical students selected Dr. Aufses to administer the Oath of Maimonides or the Oath of Hippocrates at commencement, and on three occasions he was chosen to serve as Commencement Grand Marshal. In May 2003, Dr. Aufses delivered the medical school’s commencement address and was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters.

In addition to publishing more than 235 research papers and book chapters—many on the topics of surgical education and inflammatory bowel disease—he held leadership roles in many professional organizations. These include the New York Academy of Medicine, the American College of Gastroenterology, the New York Surgical Society, the American College of Surgeons, and the American Surgical Association.

Dr. Aufses also had a keen interest in Mount Sinai’s long and storied history, and published two books on the subject with institutional archivist Barbara Niss. This House of Noble Deeds: The Mount Sinai Hospital, 1852-2002 (New York University Press, 2002), chronicled the 150-year history of The Mount Sinai Hospital, focusing on the accomplishments of the staff since its origin as The Jews’ Hospital in the City of New York. Teaching Tomorrow’s Medicine Today: The Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 1963-2003 (New York University Press, 2005), detailed the first forty years of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

In April 2017, Dr. Aufses’ support of the Archives was made clear when the Mount Sinai Archives was formally dedicated as the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives.

The staff of the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives will miss Dr. Aufses’ kindness, sense of humor, and selfless service to Mount Sinai. Dr. Aufses was calm and steady in the operating room and in life. He delighted in his trainees’ achievements, and set an example of honesty, integrity, and loyalty for those who followed him. He was a true Mount Sinai Giant.

Feb 27, 2019

To celebrate Black History Month, we would like to bring William Johnson Trent, Jr. (1910-1993), to your attention. Trent was the first African-American elected to the Board of Trustees of St. Luke’s Hospital. He was an active member of the Board from 1965 to 1977 and served four years as the Board’s President from 1970 – 1974. He remained a concerned Honorary Trustee from the time of his resignation until his death from cardiac arrest in November, 1993.

Trent was born in North Carolina and raised in Atlanta, Georgia. He attended a private high school and graduated from Livingstone College in 1930. He went on to earn an MBA from the Wharton School, followed by graduate work in economics at the University of Chicago. Afterwards, he returned to North Carolina and taught for two years at Livingstone College and later at Bennet College, where he was also an Acting Dean for a year.

He was the son of an early organizer of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Trent, Sr.’s civil rights activism seems to have been passed down to Trent, Jr., who served as Adviser on Negro Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes between 1939 and 1946, and played a part in desegregating national park facilities. Later he held the position of Race Relations Officer in the Federal Works Agency. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt invited Trent to be a part of an informal group of African-Americans, casually called the “Black Cabinet,” who served as public policy advisers to Roosevelt and his wife during Roosevelt’s administration.

Joining with Tuskegee Institute president Frederick D. Patterson, and educator and civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune, Trent was co-founder and Executive Director of the United Negro College Fund from its, start in 1944 until he left 1964, raising $78 million to support private black colleges and universities.

During the time Mr. Trent was on the St. Luke’s Board he was an Assistant Personnel Director, involved in training and personnel development at Time, Inc., retiring in 1975. He was also on the boards of the National Social Welfare Assembly of New York City, the African-American Institute, the New Rochelle Council for Unity, the Child Study Association of American, and Livingstone College. He served on the College Housing Advisory Committee, Housing and Home Finance Agency, the Advisory Committee on Governmental Operations for the City of New Rochelle and was on the Steering Committee of the African Scholarship Program of American Universities, Cambridge, Mass., and the Personnel Committee of International House, a Morningside Heights neighbor.

While Trent was a strong advocate for African-American causes, he had the ability to bring people of all color together to work for a worthy cause, which may have been what drew his nomination to the Board of Trustees at St. Luke’s Hospital and made him a beloved, and honored member of it.

Jan 11, 2019

On January 11, 1919, the Mount Sinai Hospital affiliated unit, U.S. Army Base Hospital No. 3 was officially relieved of duty. The war was over for them. All told, they had treated 9,127 patients with 172 deaths (54 surgical and 118 medical, the latter due mainly to pneumonia related to the influenza epidemic that swept the world in 1918). On March 5th, the doctors and nurses returned to New York City. The enlisted men returned two and a half weeks later.

A ward at Base Hospital No. 3

Jul 31, 2018

The Aufses Archives recently announced the opening of a new digital collection of letters to and from Abraham Jacobi, MD, the “father of American pediatrics” and a towering figure in the history both of Mount Sinai and of nineteenth-century American medicine. The letters, most of which deal with the staffing and administration of Mount Sinai’s outpatient clinics, contain the historical traces of many other physicians and surgeons who passed through Mount Sinai in the late nineteenth century. Some went on to quiet careers in private practice; others were famous in their time but have since been forgotten.

One letter in the collection, dated March 1st, 1879, contains an update from Rudolf Tauszky, MD, Secretary of the Medical Staff of the Out-Door Department (that is, the outpatient clinics), informing Dr. Jacobi of changing staff assignments. Among other changes to the roster, Doctors M.J. and E.J. Messemer had been appointed to the internal medicine clinic.

These forgotten names piqued our curiosity. Who were they? How were they related? Research confirmed that the Messemers were brothers and had graduated from Bellevue Hospital Medical College (predecessor of today’s NYU School of Medicine) a few years previously. At a time when the modern system of clinical instruction was still in its infancy, positions in the charity outpatient clinics of a prestigious hospital were a valuable way for recent graduates to gain practical experience on the way to establishing a private practice.

Further research revealed the subsequent career of Michael Jean Baptiste (M.J.B.) Messemer, MD. He turned out to have been a colorful figure who was a minor celebrity in old New York.

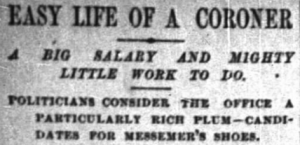

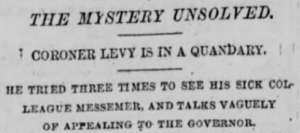

New York Times, July 21, 1890

New York Times, July 21, 1890

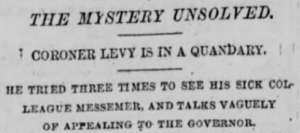

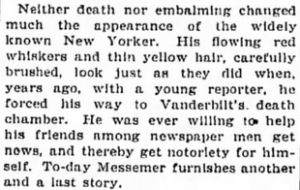

New York Tribune, May 27, 1891

New York Tribune, May 27, 1891

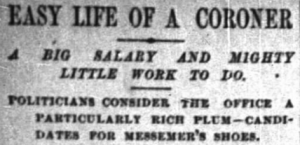

New York City in the late nineteenth century was limited to Manhattan and a portion of what is now the South Bronx, and city politics were firmly under the control of Tammany Hall, of which Dr. Messemer was a loyal member. Today, the Chief Medical Examiner of New York City is a highly regarded professional, but in the 1880s the position of City Coroner was considered a “plum” job for Tammany loyalists whose incumbents could draw a high salary with relatively little work. Dr. Messemer became one of the city’s four coroners in 1883. One colleague, Coroner Levy, charged Messemer with spending much of his time in recreational travel, pleading sickness rather than attending to his public duties. Levy remarked sarcastically to a New York Tribune reporter that “I am afraid that the public is skeptical about him.”

New York Times, December 10, 1885

New York Times, December 10, 1885

Dr. Messemer did investigate cases, however. Many of these were widely reported in the popular press, leading to accusations that Dr. Messemer was publicity-hungry and using the office of coroner to promote himself. In 1885, on the death of railroad magnate William Henry Vanderbilt, Messemer rushed to Vanderbilt’s mansion in the company of a reporter to inspect the body for foul play. A colleague accused him of “looking for notoriety,” adding that such an uninvited inspection was “wrong and uncalled for” under the Police Department rules governing suspicious deaths.

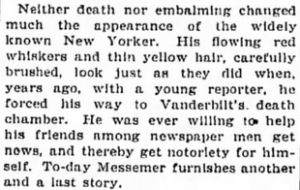

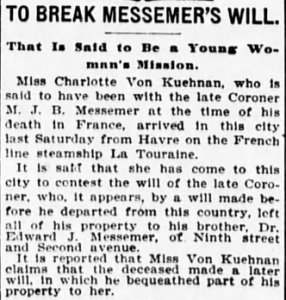

New York World, March 3, 1894

New York World, March 3, 1894

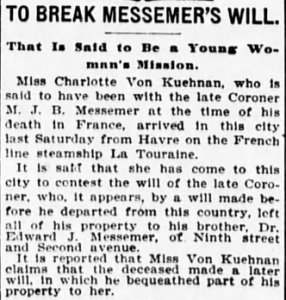

Dr. Messemer passed away in 1894 while traveling in Europe. The “widely known New Yorker,” wrote the obituary columnist of the New York World, “was ever willing to help his friends among newspaper men get news, and thereby get notoriety for himself. To-day Messemer furnishes another and a last story.” The will that Dr. Messemer had placed on file in New York left his entire estate to his brother, but his European mistress claimed he had written her into his will on his deathbed. Although she traveled to New York to contest the will in person, the suit was eventually settled in favor of his brother.

New York Evening World, April 23, 1894

New York Evening World, April 23, 1894

March is Woman’s History month and there are many notable women from within the MSSL fold to honor, but Dr. Leila C. Knox is the first notable woman I would like to highlight for Women’s History Month. Dr. Knox was the first woman to be hired as an Attending Physician on any level at St. Luke’s Hospital. Leila Knox, BA started at St. Luke’s in 1913 as an assistant and bacteriologist to Resident Pathologist Dr. J. Gardiner Hopkins. At that time, it wasn’t uncommon for educated women to work in the Pathology Labs. But long-time Director of Pathology, Dr. Francis C. Wood knew Knox wanted more out of her work and encouraged her to attend medical school. She enrolled in Cornell University Medical College. She became the Resident Pathologist at St. Luke’s in 1917, and in 1918 she added ‘MD’ to that title. Working together, she and Dr. Wood developed a surgical pathology lab of importance and value, and one which was notable in its field. She was appointed Assistant Attending Physician in 1923, a title which was unique at that time. Knox wasn’t restricted to laboratory work, but trained technicians and members of the House Staff, conducted autopsies, and made rounds as an Attending to observe patients. She published many papers generated by her efforts both as an Attending and a Pathologist, and was Assistant Editor of the American Journal of Cancer from 1930-1938, writing abstracts and original articles for the publication. She was recognized abroad and at home for her work as a tissue diagnostician. She retired in 1948 after thirty years of service, holding the title of Pathologist, Director of Laboratories and Associate Attending Physician.

March is Woman’s History month and there are many notable women from within the MSSL fold to honor, but Dr. Leila C. Knox is the first notable woman I would like to highlight for Women’s History Month. Dr. Knox was the first woman to be hired as an Attending Physician on any level at St. Luke’s Hospital. Leila Knox, BA started at St. Luke’s in 1913 as an assistant and bacteriologist to Resident Pathologist Dr. J. Gardiner Hopkins. At that time, it wasn’t uncommon for educated women to work in the Pathology Labs. But long-time Director of Pathology, Dr. Francis C. Wood knew Knox wanted more out of her work and encouraged her to attend medical school. She enrolled in Cornell University Medical College. She became the Resident Pathologist at St. Luke’s in 1917, and in 1918 she added ‘MD’ to that title. Working together, she and Dr. Wood developed a surgical pathology lab of importance and value, and one which was notable in its field. She was appointed Assistant Attending Physician in 1923, a title which was unique at that time. Knox wasn’t restricted to laboratory work, but trained technicians and members of the House Staff, conducted autopsies, and made rounds as an Attending to observe patients. She published many papers generated by her efforts both as an Attending and a Pathologist, and was Assistant Editor of the American Journal of Cancer from 1930-1938, writing abstracts and original articles for the publication. She was recognized abroad and at home for her work as a tissue diagnostician. She retired in 1948 after thirty years of service, holding the title of Pathologist, Director of Laboratories and Associate Attending Physician.