Dec 7, 2020

The Emergency Medical Service (EMS) has its roots in battlefield medical care, dating back as far as ancient Greece. American emergency medical services began to take the form we recognize today during the Civil War, when plans for medical care of battlefield injuries was organized in an intentional fashion under General George B. McClellan.

The first American civilian ambulance corps formed in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1865. New York City soon followed with its first ambulance service at Bellevue and Allied Hospital, a public hospital, in 1869, under the direction of the newly appointed NYC Sanitary Superintendent, Edward Dalton, MD, a former Union Army surgeon. Private hospitals soon followed suit.

It was common when Roosevelt Hospital opened in 1871 for patients to arrive by themselves, if mobile, or to come in aided by family or friends. However, Hospital Superintendent Horatio Paine, MD, was worried and informed the Board of Trustees that

…persons injured accidentally or overcome by heat in the immediate neighborhood of the Hospital are carried by the police almost invariably, first to the police station in 47th street, and thence by ambulance, … to the Reception Hospital in 99th street … a distance of over 2 and a half miles. Persons injured or sun-struck on the very block on which this Hospital stands, have thus been carried past its doors.

Dr. Paine feared that Roosevelt Hospital would incorrectly appear as unwilling to receive or care for emergency cases at any hour. He collaborated with other hospitals and City authorities to establish ‘casualty districts’ in the City, and in September of 1877, Roosevelt Hospital established an ambulance service for emergency care and, along with St. Luke’s, New York, and Bellevue Hospitals, provided coverage over one of the casualty districts mapped out by the City.

Horse-drawn carts were the norm from the start of Roosevelt’s service until 1900. Equipment for each of the two ambulance carts may have included tourniquets, sponges, bandages, splints, blankets, and if called for, a straitjacket. This kit was stored under the driver’s seat, along with a quart of whiskey or brandy, which was used as pain relief at that time. At first, the ambulance deployed with only a driver, but it soon became clear that an on-board physician to assess a patient’s condition and perhaps administer treatment while on route to the hospital was necessary. House staff were the first assigned to this service, in rotation. Later on a team of ‘ambulance surgeons’ was formed as a regular unit under the surgical service.

Horse-drawn carts were the norm from the start of Roosevelt’s service until 1900. Equipment for each of the two ambulance carts may have included tourniquets, sponges, bandages, splints, blankets, and if called for, a straitjacket. This kit was stored under the driver’s seat, along with a quart of whiskey or brandy, which was used as pain relief at that time. At first, the ambulance deployed with only a driver, but it soon became clear that an on-board physician to assess a patient’s condition and perhaps administer treatment while on route to the hospital was necessary. House staff were the first assigned to this service, in rotation. Later on a team of ‘ambulance surgeons’ was formed as a regular unit under the surgical service.

Ambulance service gained acceptance over time, as hospitals began to be seen as a safe place to go, a place for healing. For the year 1883, the hospital answered over 734 calls and spent $1,714.11 on feed, straw, repairs, harnesses, horseshoeing, telegraph service, purchase of horses, and also for legal expenses for accidents. That year the service also spent $1,310.92 on whiskey, wine, ale, porter, beer, and mineral waters! By its tenth year of service, ambulance calls rose to 1,122. By its twentieth year of service in 1897, total calls more than doubled the number at 3,300.

The Hospital annual report for 1899 notes that a new accident building opened with a ground floor emergency room and an ambulance court, placing more emphasis on emergency services overall. Accordingly, the service expanded to three ambulances and drivers, answering 4,041 calls.

By 1900 the horse-drawn ambulance was replaced by electric cars, which weigh 4,800 pounds and traveled at up to sixteen miles an hour. Costing $3,000.00 each, the Hospital received two as gifts – one of which was from a prominent physician of the city. The vehicles were seven feet, six inches long on the inside, eighteen inches longer than most ambulances, and had room for three reclining patients, or eight patients if they sat up. The cars were battery powered. The batteries were in a box suspended from the body of the vehicle, to be recharged each time the car returned to the Hospital. In an emergency, an extra set of batteries came with the car and could be put into place in two minutes. The batteries ran 25 miles on one charge.

Service costs ran between $3,000 and $4,000 for each vehicle in 1901 and 1902, in addition to the cost of re-fitting the necessary mechanical arrangements to store them in the old horse stables on the hospital grounds. Costs to run the service rose to $6,000 in 1903, when Hospital administrators decided to discontinue the electric cars, and return to the cheaper and more dependable horse-drawn carts.

On March 1, 1909 the ambulance service was completely discontinued, again, citing the high operational costs, partly due to the legal costs of frequent accidents. New York, Flower, and J. Hood Wright Hospitals stepped in to cover the area left without service.

That same year the State Charities Aid Association published a bill to create a Board of Ambulances – a central control agency over ambulance service in the City. Called The Newcomb-Hoey Bill, it suggested that such a Board consist of the Commissioner of Police, the Commissioner of Public Charities, and the President of the Trustees of Bellevue and Allied Hospitals. Such a Board would cover service over Manhattan and the Bronx. A sister agency, run by the Commissioner of Public Charities, would have control over Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island.

Each Board would have general control over and establish the rules and regulations governing all ambulance service in their districts, except those maintained by the Board of Health. It would establish casualty districts, and be the central clearinghouse to receive and distribute ambulance calls to the various hospital units.

The late 1930s was a time of self-assessment and re-evaluation for Roosevelt Hospital. The Hospital was nearly 70 years old and the facilities needed renovation, updating, and expansion to meet the growth of the neighborhood it served. Part of this renewal was the reintroduction of the ambulance service.

On July 5, 1939, at noon, Roosevelt Hospital resumed its ambulance service with modern motor vehicles. Two new ambulances, painted dark gray and white, cost $3,000 each. The Department of Hospitals and the Hospital shared the cost of the service’s operation. Ambulance drivers received extensive training in first aid, especially in dealing with fractures, because World War I had depleted the medical staff and a physician couldn’t be spared. The 1939 Hospital annual report lists five doctors appointed as ambulance surgeons, but they did not ride with the car unless requested by the police officer calling for it.

Prior to its discontinuation in 1909, Roosevelt Hospital’s ambulance answered calls from West 27th Street to West 86st Street and from the Hudson River to Sixth Avenue, including Central Park below 86th Street. When the service resumed in July of 1939, its area covered West 39th to West 72nd Streets between Fifth Avenue and the Hudson, including all of Central Park south of 86th Street.

In the mid-1940s the eastern border of its service was moved to the west side of Park Avenue, except for the area around Grand Central Station, which was served by Grand Central Hospital, and then again to the west side of Lexington Avenue. At this point, Roosevelt Hospital covered the largest casualty district in the City.

Emergency Department renovations in 1961, along with the closing of Grand Central Hospital that same year, forced the expansion of the ambulance district by 130 additional city blocks. The Hospital now covered midtown Manhattan from the Hudson to the East River between East 42nd Street and East 79th Street. Lenox Hill Hospital resumed its ambulance service in 1965, allowing Roosevelt Hospital to reduce its northern border from East 79th Street to East 59th Street and its eastern border returned to the west side of Fifth Avenue.

By 1946 World War II was over and New York City’s population was growing again. The ambulance service was in high demand with 9,166 calls for the year, causing the Hospital to add two additional ambulance cars to the service. The increase in demand put stress on the Accident Ward facilities, which opened in 1899. The following year, demand was even higher with 10,685 calls and 39,329 emergency cases.

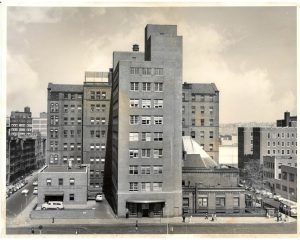

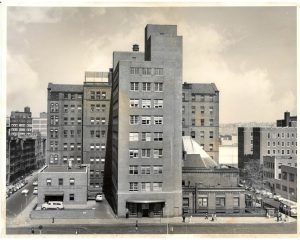

In 1947 friends of Dr. James I. Russell, a beloved and distinguished Roosevelt surgeon who had died in 1944, together with other friends of the Hospital, raised funds to construct a building to house modern accident and emergency facilities and a new surgical ward. Named the James I. Russell Memorial Building, the building featured a new, enlarged ambulance bay off 9th Avenue. The first floor handled emergency cases and the second floor was devoted to operating and treatment rooms for 46 surgical patients, and included X-Ray facilities, a plaster room, and eight observation rooms. The Hospital broke ground for the new building in August of 1948 and it opened in June of 1949.

The 1950s saw a continued expansion of the ambulance service and the upgrading and specializing of ambulance car models. In September 1956, three ambulances of a new design, made especially for metropolitan service by the Hospital Ambulance and Purchasing Department personnel, went into service. Their uniquely designed square bodies afforded room to carry four patients on stretchers, in double-decker fashion, or eight persons seated. Peter B. Terenzio, President and Director of the Hospital said the new design provided a ”functionally safe mobile unit which will permit more efficient patient care.” The new two-tone light gray ambulances were the gift of the J.P. Stevens Company, a textile concern, and the Theodore Luce Foundation.

In 1968 the Chief of Ambulance Services designed a new ambulance, for the Hospital. This ambulance, paid for with funds raised by the Hospital’s volunteer corps through the Generosity Thrift Shop, contained many life-saving devices, including an apparatus that provides vital anti-shock treatment while the vehicle is enroute from accident to Hospital.

By the 1960s automobiles were the standard mode of transportation, utilizing a growing system of roadways around the city as well as across the country. The increase in traffic provided an additional challenge to public health and safety. This problem was brought to national attention when President John F. Kennedy noted that, “Traffic accidents constitute one of the greatest, perhaps the greatest, of the nation’s public health problems.” In 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared that traffic accidents were, “…the neglected disease of modern society.”

In 1970 the National Highway Traffic Safety Act was adopted. Amongst several things, the Act standardized EMS training and urged the adoption of a single emergency number countrywide. Use of the 911 emergency number began in 1968, but was slow in gaining acceptance by every state. In 1973 the Federal EMS Systems Act was established, forming 300 EMS systems across the country, including NYC EMS, and the beginning of sweeping changes in EMS care and development across the country.

In the 1970s to 1990s, NYC’s EMS operated under the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, which dispatched both its own ambulances and hospital-owned ambulances. On March 17, 1996, NYC EMS merged with the Fire Department of New York (FDNY), forming the Bureau of Emergency Medical Services. FDNY EMS now controls the operation of all ambulances in the NYC 911 system, 70% of which are FDNY-based and 30% hospital-based, supplemented by private ambulance services.

Nov 24, 2020

Whenever you look back to the past, it is easy to find it all very strange, but a longer look allows us to see the threads that connect that time to this. Some of those threads are strong and enduring and others fray and end.

One of those strong threads that tie the Mount Sinai of 100 years ago to the Mount Sinai of 2020 is research and discovery. In 1920, Mount Sinai was dealing with the last wave of a deadly worldwide pandemic that had started in 1918 but still lingered. Some Mount Sinai physicians spent a great deal of time working on a “peculiar disease” that followed the epidemic. This was popularly called the ‘sleeping sickness,’ but doctors termed it epidemic encephalitis. Another Mount Sinai physician was lending his expertise as a member of a national commission that was established to deal with the ravages of empyema, which too often followed post-influenzal pneumonia. Other physicians were doing research on gastric diseases, leukemia, surgical innovations and cardiac problems – all topics that Sinai doctors continue to pursue.

Taken from 5th Ave. and 99th St. looking east over the new buildings. The building facing with the flag pole is the 1904 main building.

Another main theme from 100 years ago, as in every decade of Mount Sinai’s existence, was the physical changes being made on campus. The world war and epidemic had delayed the progress of the largest expansion plan ever envisioned by The Mount Sinai Hospital. First suggested in 1913, it was only in 1922 that all of the new buildings were completed and the renovations of older spaces finished. This resulted in a new Private Pavilion (our current Kravis Children’s Hospital), a new pediatric pavilion and pediatric clinic building, a larger employee dormitory, a larger laboratory building, and a new auditorium to accommodate Mount Sinai’s increasing educational efforts. The growth in the number of beds called for a larger house staff than before and allowed for the growth of new specialty services.

W hile these themes have echoes with our current year, as does the perennial nursing shortage of that era (among many others), there was much that was unique to Mount Sinai in 1920. In February of that year, Mount Sinai leaders held an event to celebrate the staff that had served in the World War I Mount Sinai affiliated unit, Base Hospital No. 3. Special commemorative medals were given to each veteran.

hile these themes have echoes with our current year, as does the perennial nursing shortage of that era (among many others), there was much that was unique to Mount Sinai in 1920. In February of that year, Mount Sinai leaders held an event to celebrate the staff that had served in the World War I Mount Sinai affiliated unit, Base Hospital No. 3. Special commemorative medals were given to each veteran.

The other topic of great interest in 1920 was the re-structuring of the medical staff to combine the in-patient and out-patient services under the in-patient chief of service. The Dispensary and the ward service had been two separate entities with limited overlap. The change allowed the clinic physicians to follow their patients when admitted to the hospital wards, and the ability to round and work with the in-patient staff made it more appealing to community physicians to take on clinic work. In the 1920 Annual Report, it was noted that the combined medical staff now numbered 250 physicians.

Certainly, times change. Institutions changes. Medicine changes. But even 100 years later, at Mount Sinai, some things never change.

Nov 9, 2020

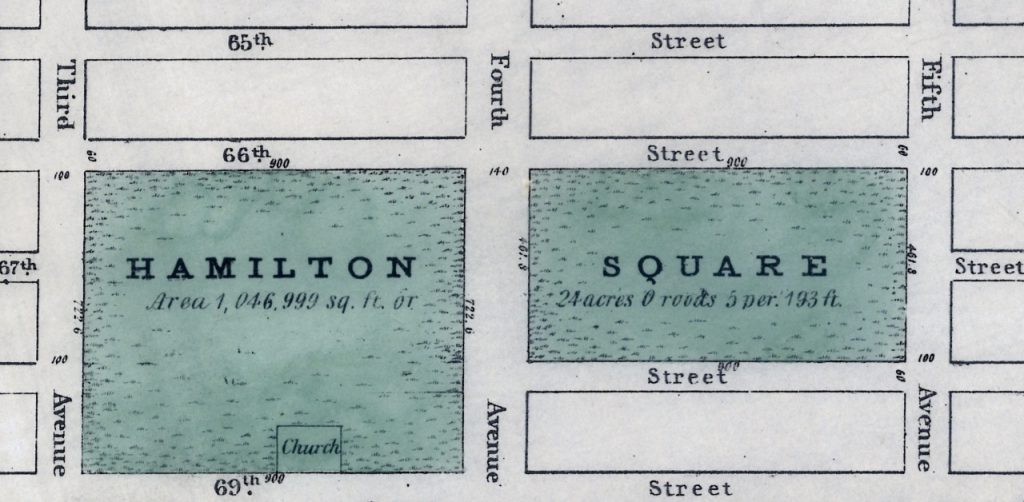

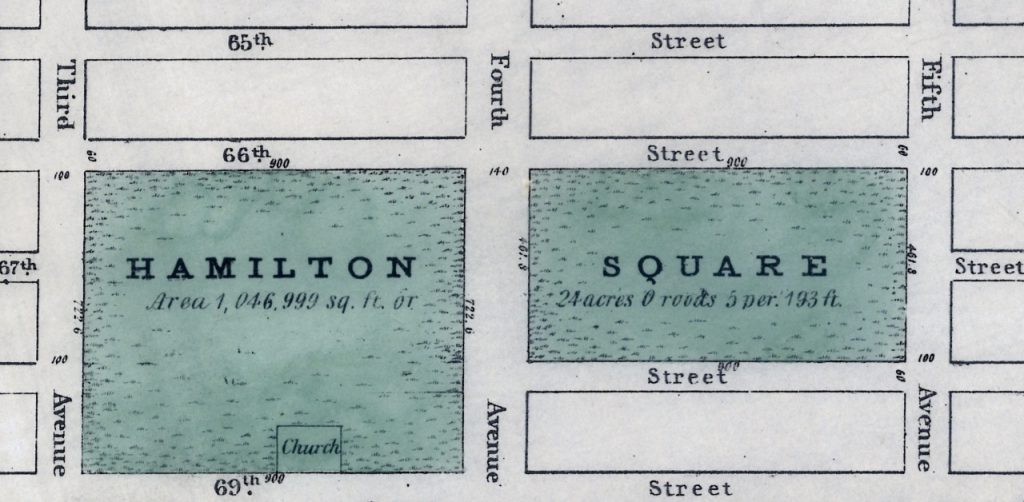

I recently read a piece about Hamilton Square in the Roosevelt Island Historical Society’s From the Archives email. This park, which was named for Alexander Hamilton, existed on the Upper East Side of Manhattan from around 1807-1869. I found this fascinating since The Mount Sinai Hospital moved to Lexington Ave. and 66th St. in 1872. I knew that the City had ‘seeded’ this area with non-profit entities: Hunter College, many hospitals and schools, but I had never heard about the Square itself, which ran from 66th to 69th Streets between 3rd and 5th Avenues. Finally, Mount Sinai had a Hamilton connection, even though he died in 1804, 48 years before the Hospital was created!

Map of Hamilton Square from the New-York Historical Society

When the Square was broken up, The Mount Sinai Hospital (MSH) was located on W. 28th Street, between 7th & 8th Avenues. It had been founded in 1852 as the Jews’ Hospital in the City of New York (the name was changed in 1866) and had opened its first building in 1855. After the Civil War, the leadership realized that the facility was inadequate and the location less than ideal due to the growth of the City. On November 2, 1867 the Directors authorized the purchase of ten lots of land from 65th to 66th Street on the west side of Park (then 4th) Ave. and later added eight more lots there. But then on October 6, 1868, the City leased Mount Sinai twelve lots of land between 66th and 67th on Lexington Ave. for $1 a year for 99 years. Somehow, over the interim, the City and Mount Sinai had reached an agreement on the Hospital taking over part of the former Hamilton Square. The earlier lots were later sold, saving Mount Sinai thousands of dollars. On May 25, 1870, the cornerstone for the second MSH was laid. The President of the Hospital, Benjamin Nathan, and Mayor Oakley Hall were there. (Within two months, Nathan was murdered in his bed on a ‘dark and stormy night.’)

On May 29, 1872, a dedication ceremony was held for the new Mount Sinai Hospital. When the building opened, it had a greatly expanded capacity of 110 beds. The building was designed by the well-known architect, Griffeth Thomas, and cost $335,000 to complete. It had an operating room in the basement of the north wards, rooms for our newly created House Staff to live in, a meeting room for the Directors, and a synagogue. Lexington Ave. remained unpaved for two more years, and the Hospital never wired the facility for electricity. A telephone was installed in 1882; the number was “Thirty-Ninth St., 257”. It was at this site that Mount Sinai transformed into what we would recognize as a modern hospital, with medical education and research joining its core mission of providing patient care.

In typical Mount Sinai fashion, this facility quickly became too small. Additional buildings were built and major renovations were begun in 1882. In 1890, Mount Sinai added a building across from the Hospital on the north side of 67th St. for our nursing school and Out Patient Department. This building is the only remnant of Mount Sinai that remains there today. It later served as the home of the Neurological Institute, the Polish legation, and finally became a school for the Archdiocese of NY. The Mount Sinai Hospital moved from Lexington Ave. in 1904 to its current East Side location on 100th St., between Madison and 5th Avenues. The name of Hamilton continues on various buildings and neighborhoods of the City, making its most recent appearance on Broadway.

Oct 29, 2020

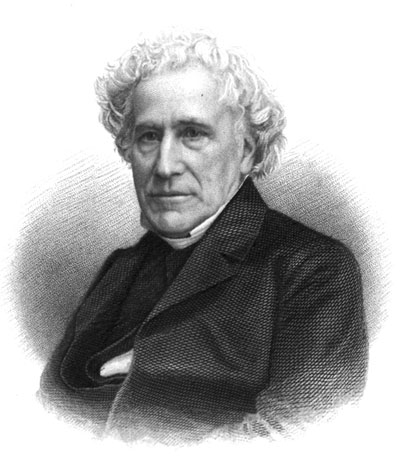

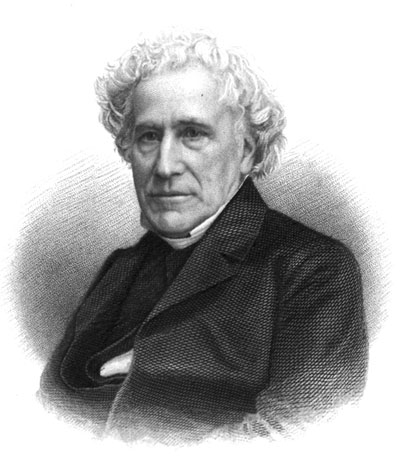

Mount Sinai Morningside, originally the St. Luke’s Hospital, celebrated the 174th anniversary of its founding on October 16th this year. The true founding date for the hospital is October 18th, the feast of St. Luke on the liturgical calendar. On that day in 1846, Rev. William A. Muhlenberg announced to his Church of the Holy Communion congregation his intention to found a hospital to ease the suffering of the sick poor of the city. It would be a “Hôtel Dieu” (hotel of God), that would treat its patients as guests, with care and compassion, as all the guests are ill. Founder’s Day honors that spirit of care and compassion as the staff continues to put patients first, keeping our values of empathy, optimism, safety, transparency, creativity, agility, and teamwork in the forefront.

Mount Sinai Morningside, originally the St. Luke’s Hospital, celebrated the 174th anniversary of its founding on October 16th this year. The true founding date for the hospital is October 18th, the feast of St. Luke on the liturgical calendar. On that day in 1846, Rev. William A. Muhlenberg announced to his Church of the Holy Communion congregation his intention to found a hospital to ease the suffering of the sick poor of the city. It would be a “Hôtel Dieu” (hotel of God), that would treat its patients as guests, with care and compassion, as all the guests are ill. Founder’s Day honors that spirit of care and compassion as the staff continues to put patients first, keeping our values of empathy, optimism, safety, transparency, creativity, agility, and teamwork in the forefront.

This year’s celebration included posters and balloons decorating the lobby of the Main Hospital where volunteers and staff distributed delicious anniversary cookies, bearing the image of Rev. Muhlenberg himself, to staff. The cookies were provided through a gracious private donation. St. Luke’s Café offered a special 1850s-era meal of pot roast, mashed potatoes and green beans, courtesy of Café manager, Michael Shapiro.

A virtual program began with a message from Chaplin, Meredith Lisagor, who spoke about the founding values of the Hospital, which continue to be upheld by the staff today, followed by an encouraging message by President Arthur Gianelli, who also announced the upcoming 175th anniversary of the founding of the Hospital in 2021. Segments from the video, For the Common Good, relating the history of St. Luke’s Hospital through the late 1970s merger with Roosevelt Hospital were shown. Originally made to celebrate the 150th/125th anniversaries of the former St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospitals, the film features images of New York City in the early 20th century as well as many historical images of St. Luke’s Hospital from the Hospital’s archival collections. The complete version of this film is available for viewing on the Icahn School of Medicine YouTube channel at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HtrMsIh4STI.

The main segment of the Zoomcast featured Dr. Erna Kojic, Chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases, Mount Sinai Morningside and Mount Sinai West speaking about, “Global Pandemics 1918 and 2020: What Have We Learned?” This enlightening talk compared and contrasted the Spanish Flu and Covid-19 pandemics, drawing the conclusion that there are many similarities to the two events, but the public response to them has not changed much despite the one hundred two years between them.

The event ended with a surprise when Dr. Carl Braun presented the Spirit of Compassion award to wife Dr. Norma Braun while on Zoom. The award honors those who brings commitment and compassion to their caregiving at Mount Sinai Morningside and exemplifies the MSM and MSHS Values. Congratulations and well-done, Dr. Norma Braun.

Oct 16, 2020

Our web archives are available online here.

In March 2020, the world began witnessing history in real-time, and archivists scrambled to ensure that the story of COVID-19 would be well-preserved. But with so much happening at a distance, much of the communication and ephemera created in the last six months is online, meaning that archivists have had to eschew traditional practices in collecting physical material and focus increasingly on the enormous amount of material now online. For example, at the peak of the crisis, healthcare institutions like Mount Sinai were updating their websites multiple times a day so that staff and the public had the best and most recent information on policies and procedures regarding things like new treatments and personal protective equipment. This type of information will be valuable moving forward as historians try to understand a rapidly evolving crisis.

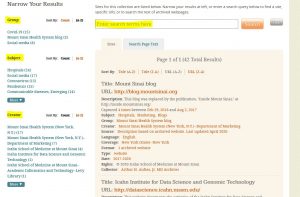

Fortunately, technology exists to capture every version of these websites as they appear online. Web archiving has been a practice since the late-1990s, and since 2015 the Aufses Archives has used Archive-It, a web archiving service provided by the Internet Archive, to regularly capture information related to the Mount Sinai Health System. We also use this tool to capture web content related to the response to COVID-19, as well as day-to-day changes to the website.

Screenshot of the Aufses Archives page on Archive-It.

The easiest way to access our web archives is to browse the list of websites on the main screen. These results can be filtered using the groups, subjects, or creators on the left side of the screen. You can also use the search bar at the top of the screen to search the metadata created by the archivist. (We expect our COVID-19 group to be the most used group for the foreseeable future.) Information on COVID-19, as well as a wide range of subjects, has been collected by a number other academic institutions, and you can also browse their collections here.

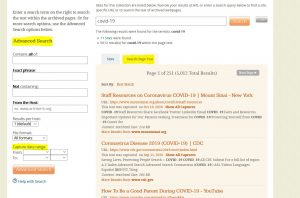

If you’re searching for a particular webpage instead of a whole website, or if you’re trying to search the original text of a website, the “Search Page Text” option may be of use. This feature supports keyword searching of individual web pages, much like Google. However, you can also filter by “Capture date range” which means you can search not just across subjects, but also across time.

Screenshot of the “Search Page Text” functionality in Archive-It, after searching “COVID-19.”

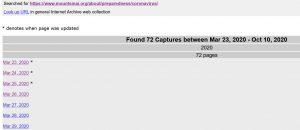

With either searching method, once you’ve selected a link, you’ll be taken to a page of dates, each corresponding to a particular date of capture. While there’s no guarantee that every version of the website was captured, it will at least give you a sense of how the site has progressed over time.

This page, related to the COVID-19 pandemic, had 72 captures at the time of writing, starting every day from March 23, 2020, to May 12, 2020. The crawl now occurs monthly, due to fewer updates of the website.

Once you’ve selected a date, you’re taken to a version of the website captured on that date. Shown below is our earliest Archive-It capture of the Mount Sinai Hospital homepage, as it appeared in February 2015. The website should play back in the same was as it originally appeared.

Of course, the Mount Sinai Health System only represents a very small corner of the internet, and archivists are working to capture as much as possible. All the websites captured by the Aufses Archives contribute directly to the Internet Archives’ Wayback Machine, which at the time of writing has 477 billion website captures, including a limited number of Mount Sinai webpages dating back to the 1990s, captured on an ad hoc basis. You can also contribute by adding URLs via the link on the Wayback homepage.

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Horse-drawn carts were the norm from the start of Roosevelt’s service until 1900. Equipment for each of the two ambulance carts may have included tourniquets, sponges, bandages, splints, blankets, and if called for, a straitjacket. This kit was stored under the driver’s seat, along with a quart of whiskey or brandy, which was used as pain relief at that time. At first, the ambulance deployed with only a driver, but it soon became clear that an on-board physician to assess a patient’s condition and perhaps administer treatment while on route to the hospital was necessary. House staff were the first assigned to this service, in rotation. Later on a team of ‘ambulance surgeons’ was formed as a regular unit under the surgical service.

Horse-drawn carts were the norm from the start of Roosevelt’s service until 1900. Equipment for each of the two ambulance carts may have included tourniquets, sponges, bandages, splints, blankets, and if called for, a straitjacket. This kit was stored under the driver’s seat, along with a quart of whiskey or brandy, which was used as pain relief at that time. At first, the ambulance deployed with only a driver, but it soon became clear that an on-board physician to assess a patient’s condition and perhaps administer treatment while on route to the hospital was necessary. House staff were the first assigned to this service, in rotation. Later on a team of ‘ambulance surgeons’ was formed as a regular unit under the surgical service.

hile these themes have echoes with our current year, as does the perennial nursing shortage of that era (among many others), there was much that was unique to Mount Sinai in 1920. In February of that year, Mount Sinai leaders held an event to celebrate the staff that had served in the World War I Mount Sinai affiliated unit, Base Hospital No. 3. Special commemorative medals were given to each veteran.

hile these themes have echoes with our current year, as does the perennial nursing shortage of that era (among many others), there was much that was unique to Mount Sinai in 1920. In February of that year, Mount Sinai leaders held an event to celebrate the staff that had served in the World War I Mount Sinai affiliated unit, Base Hospital No. 3. Special commemorative medals were given to each veteran.

Mount Sinai Morningside, originally the St. Luke’s Hospital, celebrated the 174th anniversary of its founding on October 16th this year. The true founding date for the hospital is October 18th, the feast of St. Luke on the liturgical calendar. On that day in 1846, Rev. William A. Muhlenberg announced to his Church of the Holy Communion congregation his intention to found a hospital to ease the suffering of the sick poor of the city. It would be a “Hôtel Dieu” (hotel of God), that would treat its patients as guests, with care and compassion, as all the guests are ill. Founder’s Day honors that spirit of care and compassion as the staff continues to put patients first, keeping our values of empathy, optimism, safety, transparency, creativity, agility, and teamwork in the forefront.

Mount Sinai Morningside, originally the St. Luke’s Hospital, celebrated the 174th anniversary of its founding on October 16th this year. The true founding date for the hospital is October 18th, the feast of St. Luke on the liturgical calendar. On that day in 1846, Rev. William A. Muhlenberg announced to his Church of the Holy Communion congregation his intention to found a hospital to ease the suffering of the sick poor of the city. It would be a “Hôtel Dieu” (hotel of God), that would treat its patients as guests, with care and compassion, as all the guests are ill. Founder’s Day honors that spirit of care and compassion as the staff continues to put patients first, keeping our values of empathy, optimism, safety, transparency, creativity, agility, and teamwork in the forefront.