Sep 25, 2020

Some of you may have read the sad story about the murder of a woman in the Justice Story column of the Daily News on Sunday. It is about how Irma Pradier thought she was going to run off with her boyfriend to California, but instead she was found murdered the next day along the Harlem Speedway, today known as the Harlem River Drive. I was particularly interested in this because it noted that she had been a maid at The Mount Sinai Hospital, and had even lived at the Hospital. I also realized that she had been hired before 1937, which meant there was a good chance the Aufses Archives had some record about her in our one existing employee logbook, which dates from 1882-1937. This lists all persons hired to work at Mount Sinai, which would exclude the medical staff who were generally not paid anything, or worked under a contract model.

And I was right!

Below is a portion of the page from our logbook that includes Irma Pradier. You can see from this she was hired February 13, 1934 and she lived ‘In,’ which would have meant the Employee Dormitory that faced 99th St., near Madison Ave. (across from today’s Atran and Berg buildings.) She was hired to be a Maid in the OPD (Out-Patient Department) for $35/month. (She would have also received a free meal as part of her compensation.) When she resigned on July 19, 1937, she had advanced to $47/month. As the News‘ article says, her reason for leaving is listed as “Going to Calif.” And the rest is history, or at least, an article in the Sunday Daily News.

The Irma Pradier entry from The Mount Sinai Hospital Employee Logbook

*The book is organized chronologically under each letter of the alphabet. Every entry was done by hand by an employee of the Personnel Office. This was THE official employment history of each worker. The blue bottom edge is from a long ago ink spill that saturated the pages. Note the other reasons for leaving employment. Some are fascinating!

Aug 27, 2020

This is a guest blog post by summer intern, Lily Stowe-Alekman. Lily is a junior at Smith College where she studies History, Archives, and the Study of Women and Gender.

Even before given access to traditional pathways of change, women at The Mount Sinai Hospital have worked to make change in the institution. From the opening of The Mount Sinai Hospital in 1855, the wives and daughters of the Board of Trustees worked to provide services in order to provide comfort to patients and to address their social and emotional well-being. By 1917, the first year that women were allowed on the Board, the role of women, and their expectations of that role, had substantially changed. The growing power of women was expressed by the creation of their own organization to exert influence over the life of the Hospital, the Social Service Auxiliary. And according to Helen Rehr, DSW, the second Edith J. Baerwald Professor of Community Medicine (Social Work), they were a force to be reckoned with.1 When prompted in an interview about the Auxiliary, “…they weren’t social butterflies having their tea. That’s not an image you would draw,” Rehr responded “Not these women, never. In the 28 years that I’ve known them I don’t recall having tea with them. No, they were women who came with a commitment to the social organization.” Hortense Hirsch, who served on the Auxiliary Board and Board of Trustees as one of the first woman able to be a Trustee, is a powerful example of the trailblazing women of the Auxiliary Board.

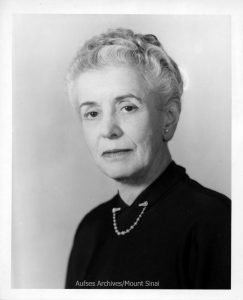

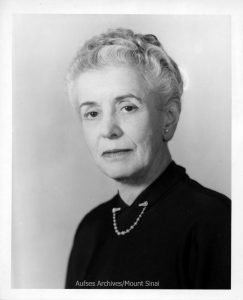

A portrait of Hortense Hirsch, circa 1960.

In 1923, Mrs. Hortense Hirsch (1887-1990) began her work with the Social Services Auxiliary (today’s Auxiliary Board), of which she would continue to be a member for sixty-five years, including a tenure as president from 1951-1956. From there, she was elected to the Board of Trustees in 1932, where she remained until becoming an honorary trustee in 1986. She sat on several committees of the Board, including as a member of the Committee on Building Maintenance and Equipment, Vice-Chairman of the Committee on Social Service, Chairman of the Committee on Convalescent Care, and as a member of the Committee on Ladies’ Auxiliary. Hirsch was president of the Neustadter Home for Convalescents beginning in 1937 when the Home affiliated with Mount Sinai, until she stepped down from the post in 1953.

A photograph of (from left to right) Helen Benjamin, member of the Women’s Auxiliary Board; Mrs. Edith Lehman, the first President of the Auxiliary Board from 1916-1917, Mrs. Ruth Cook, President from 1917-51; and Mrs. Hortense Hirsch, the presiding President of the Board at the fiftieth anniversary of the Auxiliary Board in 1956. Helen Benjamin holds a picture of the first social work volunteer from 1907.

Hortense Hirsch lived to be 103 years old, and by all accounts she remained steadfast in her dedication to social work and volunteerism for her whole life. After she graduated from Smith College in 1907 at the age of 19, she married Walter Hirsch and then moved to New York City in 1909. She began her work as a volunteer at Mount Sinai in 1917. The Federation of Jewish Philanthropies later referred to her as the “honorary ‘Dean of Social Work Volunteers.’” As a thoroughly involved volunteer and then Auxiliary Board member, Hirsch dedicated many hours to the hospital. Dr. Helen Rehr remarked in 1982, “The demands on her were great, but she always rose to it. There was no question on that score.”

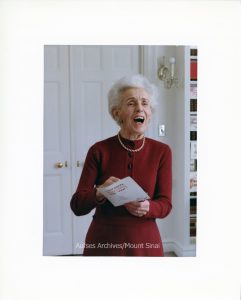

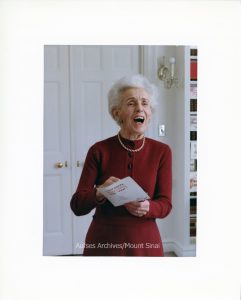

Portrait of Hortense Hirsch, circa 1976.

Hortense Hirsch’s personality leaps off the pages of archival materials. When at Smith College, she maintained her own horse and buggy, which was against the rules, by paying a farmer for boarding, effectively evading the administration. In a New York Times article documenting her 100th birthday celebration, her daughter Carol Kridel told them, that while Hirsch was too ill to attend and she had to stay in bed, she was still “wearing a pink bedjacket and a pink bow in her silver hair.” The article also includes a story of Hirsch “[coming] to her 85th birthday and [tossing] her skirts high to show she approved of the latest rage—hotpants.”

Hortense Hirsch’s work on the Social Service and Women’s Auxiliary Board helped to transform the hospital. She worked tirelessly as a volunteer and board member. Hirsch’s work and legacy came from and continued those of the women who originally found pathways to affect changes at The Mount Sinai Hospital in the late 1800s. Hirsch served on the Board of Trustees, an opportunity that was not available to the women of previous generations. As Dr. Helen Rehr stated, “the Mrs. Hirsches are an outgrowth of that group of women who were the wives of the board of trustees” and ultimately transformed the hospital in the process.

Aug 21, 2020

This is a guest blog post by summer intern, Lily Stowe-Alekman. Lily is a junior at Smith College where she studies History, Archives, and the Study of Women and Gender.

As a summer intern with the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives, I have become acquainted with Mount Sinai’s history and the efforts that go into preserving its legacy. One of the projects I have worked on is cataloging The Mount Sinai Hospital News, an in-house tabloid-style newsletter for Mount Sinai employees. Colleen Stapleton, Patient Navigator for the Liver Education & Action Program at Mount Sinai, volunteered with the Archives this spring and digitized the newsletters from 1958-71. In my work cataloging, I read some really entertaining stories that offered a glimpse into the personal lives of people who worked in The Mount Sinai Hospital (later Medical Center), whether that be birth announcements of their children, quirky stories about the things employees did outside of the hospital, or articles about celebratory dinners and ceremonies. One can also not forget the hospital’s bowling team.

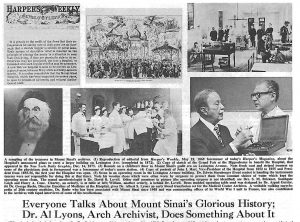

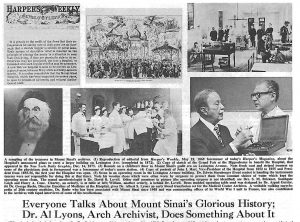

While cataloging in July, I came across a story that made me pause because it felt like a full circle moment. The October 1971 issue of The Mount Sinai Medical Center News featured an article called “Everyone Talks about Mount Sinai’s Glorious History; Dr. Al Lyons, Arch Archivist, Does Something About It.” This article has history of the Aufses Archives and is within the archive. While the Aufses Archives is a site of historical preservation, it has its own history as well.

Caption: The objects featured in the article header are still in the Arthur H. Aufses Jr. MD Archives today!

The creation of what is now the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives is due to the work and advocacy of Dr. Albert S. Lyons in the 1960s to 1980s. Over this time, Dr. Lyons advocated for the need of creating the archive and in 1986, secured its future with the hiring of a full-time archivist, Barbara Niss, who remains the Director today. Dr. Lyons (1912-2006) spent over sixty years of his life working at Mount Sinai. He began as a surgical resident at Mount Sinai Hospital in 1938. He went on to become the founder and Chief of the Intestinal Rehabilitation Clinic and worked to help support patient needs post-surgery. He was also a Clinical Professor of Surgery at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. He wrote a well-known book, Medicine: An Illustrated History, a volume of over six hundred pages, charting medicine from the prehistoric era to the twentieth century.

Beyond his clinical work, Dr. Lyons was committed to Mount Sinai’s institutional history and to history of medicine in general. He taught the History of Medicine elective courses in the medical school. In the 1960s, he convinced the hospital board to collect the institutional history of the hospital. In 1966, he was made Hospital Archivist by Mr. Gustave L. Levy, the Chairman of the Board of Trustees. Dr. Lyons’ passion for preserving the history of The Mount Sinai Hospital overlapped with the discussions and planning of Mount Sinai School of Medicine, which welcomed its first students in the fall of 1968. In 1970, he was given the official title of Medical Center Archivist. Dr. Lyons also contributed a broad range of valuable materials to the Archives, including over eighty-five oral history interviews dating to 1965, a formative time for the field of oral history as well as for the Medical Center, as the School planned for and welcomed its first students.

In October of 1971, The Mount Sinai Medical Center News wrote about Dr. Lyons’ archival work. The article highlights the work and efforts of Dr. Lyons and serves as a call to action of sorts for the archive. Dr. Lyons is quoted in the first line as saying, “When in doubt, don’t throw it out.” He goes on to say that “too much of Mount Sinai’s past has already gone up in smoke,” due to people throwing out items without realizing their significance. He stresses as well that ordinary everyday materials are archival. He stresses that history is not necessarily in the distant past, that the events of the previous day are history. In this sense, Dr. Lyons de-mystifies the archives by showing that it should be in connection with the present moment and is not a disconnected abstract institution. The closing paragraph of the article instructs readers, “If you’ve uncovered some papers or objects you think may be worth saving, are planning some event to make current Medical History, etc. Drop Dr. Lyons a note.” In turn, “He and the Future will thank you!”

SOURCES

Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives and Records Management. “Lyons, Albert S., MD, Papers, 1932-2000.” Collection Guides. https://icahn.mssm.edu/about/ait/archives/collection/albert-lyons.

Aufses, Arthur H., Jr., and Barbara Niss. This House of Noble Deeds: The Mount Sinai Hospital, 1852-2002, New York University Press, 2002. ProQuest Ebook Central, xi.

“Everyone Talks About Mount Sinai’s Glorious History; Dr. Al Lyons, Arch Archivist, Does Something About It.” Mount Sinai Medical Center News. October 1971. 5, 10.

Aug 12, 2020

George Nicholas Papanicolaou was born in the seaport town of Kymi, on the Greek island of Euboea, on May 13, 1883. He entered medical school to please his father, Nicholas, who was a physician, and the mayor of their town. He graduated medical school in 1904. In 1906, after completing military service obligations, he joined the family practice, but was more inclined to scientific research.

George Nicholas Papanicolaou was born in the seaport town of Kymi, on the Greek island of Euboea, on May 13, 1883. He entered medical school to please his father, Nicholas, who was a physician, and the mayor of their town. He graduated medical school in 1904. In 1906, after completing military service obligations, he joined the family practice, but was more inclined to scientific research.

[photo: George Nicholas Papanicolaou (1883–1962) (obtained by public domain at http://www.hmsny.org/en/archivesgallery/news-bulletins/hms-ny-news-April-2012.html). ]

In 1907, he moved to Germany to study zoology, earning a PhD in 1910. Afterwards, Papanicolaou worked as a physiologist. In 1913, he and his wife immigrated to New York. He worked in various odd jobs for a time until he was able to find part-time employment in the Department of Pathology and Bacteriology of the New York Hospital. A year later he moved to the Department of Anatomy at Cornell Medical School and worked as an assistant; his wife was hired there as his technician.

His assignments included studying sex determination in guinea pigs. Part of this testing required harvesting the animals’ eggs just before ovulation, a guessing game that usually meant killing many of them before finding an animal at the right stage to be useful to the study. Instead, Papanicolaou developed a method to chart a guinea pig’s menstrual cycle by using a nasal speculum to take vaginal swabs and preparing a smear slide, which, under a microscope displayed distinctive cytologic patterns that helped him predict ovarian status. Eventually he broaden this method to human subjects to study similar smears in women. (Some have speculated that his wife was his first subject in this study.) He was surprised to find malignant cells present in some of these smears, which led to further study. In 1928, he presented a paper on the smear procedure as a method to detect cervical cancer in women. Unfortunately, this report was not well received by the general field.

He began on a clinical study collaboration with Herbert F. Traut, MD, a gynecologic pathologist at Cornell, in 1939. During this study, Papanicolaou detected many asymptomatic cancer cases, some in such an early stage that they were undetectable on biopsy. Traut and Papanicolaou published a paper titled, “Diagnosis of uterine cancer by the vaginal smear,” in 1943, which was a step forward in accepting the ‘Pap smear’ a standard procedure for detecting and preventing cervical cancers.

Why am I telling you this? Dr. Papanicolaou served as consulting OB-GYN staff for St. Luke’s – Woman’s Hospital Division from the 1956 to the early 1960s.

Jul 6, 2020

This started out as a story about Althea Gibson, the first African American to win at Wimbledon, which she did on July 6, 1957. It was also about a summer sport, and being outside – two things people today find important and hopeful. But, as often happens in the Archives, those stories reminded us of other stories, which are, of course, about Mount Sinai.

In 1950, Harlem-born Althea Gibson made her U.S. Open debut at a time when tennis was largely segregated. On July 6, 1957, when she claimed the women’s singles tennis title, she became the first African American to win a championship at London’s All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, aka Wimbledon. (Arthur Ashe was the first African American to win the men’s singles crown at Wimbledon in 1975. Ashe later had quadruple bypass surgery at St. Luke’s Hospital in 1979.) The Associated Press named Althea Gibson Female Athlete of the Year in 1957 and 1958. During the 1950’s, Gibson won 56 singles and doubles titles, including 11 major titles. Gibson retired from tennis and later became a professional golfer. She was voted into the National Lawn Tennis Association Hall of Fame in 1971 and died in 2003.

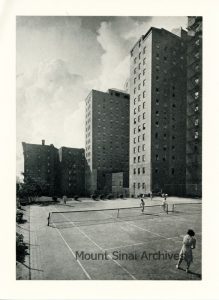

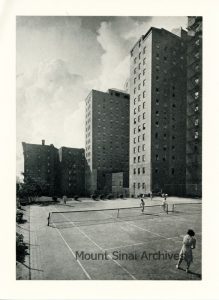

The Mount Sinai Hospital tennis courts on 5th Ave and 99th St, behind 5 E. 98th St., where KP is today.

Tennis has a long, up-and-down history at Mount Sinai. The first tennis court was built at the Hospital in the late 1800’s, back when the Hospital was still located at Lexington Avenue and 67th St. Space was tight, so the court was built between buildings, and the only way to get to it was to climb through a window on one of the wards. (Fortunately, a gong would sound whenever an Attending arrived at the Hospital, so the players were warned to get back inside.) In 1904, Mount Sinai moved uptown to 100th St., and it took 20 years before tennis returned. The growing House Staff asked the Trustees to build tennis courts that they could use for exercise. The Trustees

A small pewter trophy belonging to Noreen McGuire, School of Nursing Class of 1932. The trophy was for winning the tennis tournament in 1929.

eventually agreed in June 1923 and two courts were built on the southeast corner of 99th St and 5th Ave. Mount Sinai had purchased the land for future expansion needs, but had recently completed major additions to the campus and had no immediate plans to build. The courts were used by the Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing for gym classes, and nurses and doctors could sign up to play when a court was free.

The Aufses Archives has a wonderful interview with Gus Burton from 1988. Mr. Burton joined Mount Sinai’s staff in 1948, first as an x-ray file clerk, and then later trained as a technician in the Dept. of Radiology. What initially attracted him to work at Mount Sinai was because there was a tennis court. Here is how he described it:

Burton: …Back in those days the buses that ran along Fifth Avenue were owned by a company called the Fifth Avenue Bus Company. They had double deckers. The top deck was so that you could ride the bus for a nickel. At the time I was a student at NYU and sometimes I would take the bus down because the classes were at Washington Square. It was almost like a bus tour going down Fifth Avenue, seeing all the different places, and I saw the Hospital. I wasn’t impressed with the hospital so much, but where Klingenstein is there used to be tennis courts. At that time I was an avid tennis player, and I could see these people playing tennis. I thought it was very, very interesting, because I had found that there weren’t many places to play tennis in New York and here these people were running around playing tennis. Eventually, one day I was coming back home and I got off the bus. It was approaching the end of the semester and I said I need to find some kind of work for the summer. It was raining pretty hard, so I ran under the canopy that they had by the [Guggenheim] Pavilion. So I said, let me just check in here and see what’s going on. In those days, they didn’t really have what you call a personnel office. I guess they called it an employment office. They had about one or two clerks and the person who ran it, a Mr. Kerr (?). I just walked in and asked them if they had any jobs available. Said Mr. Kerr, “we may have some available in the radiology department. We’ll refer you to the person there who is looking for somebody and see what happens.”

So I went over and I was interviewed by a Dr. Joan Lipsay. She was the second in command in the radiology department. She was just really impressed that I came along and, sure, we’ll take you and they hired me as an X-ray file clerk. So I have always said in the years since then, that I had enough sense to come in out of the rain.

Interviewer: Did you ever get to play tennis?

Burton: Well, I found out after I started working here that those tennis courts were for the professional staff, the doctors and the nurses, and they were the ones I had seen playing on them. It so happened that one of the radiologists on our staff was an avid tennis player, he used to play out there frequently so I was able to get with him and I did get a chance to play on those tennis courts.

Unfortunately for Mr. Burton, the tennis courts were closed later in 1948, when Mount Sinai began the process of building the Klingenstein Pavilion along 5th Ave. It would be 65 years before tennis came back to Mount Sinai, but this time it was in a much different form. In 2013, it was announced that The Mount Sinai Medical Center was now the official medical services provider for the United States Tennis Association (USTA) and the U.S. Open. In addition, Alexis C. Colvin, MD, from the Leni and Peter W. May Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, would serve as the USTA’s Chief Medical Officer. In 2020, this continues to be the case. Every now and then, a mini-tennis court is built in the Guggenheim Pavilion lobby to showcase the Hospital’s role with the USTA, and for a brief moment, tennis is played again at Mount Sinai.

George Nicholas Papanicolaou was born in the seaport town of Kymi, on the Greek island of Euboea, on May 13, 1883. He entered medical school to please his father, Nicholas, who was a physician, and the mayor of their town. He graduated medical school in 1904. In 1906, after completing military service obligations, he joined the family practice, but was more inclined to scientific research.

George Nicholas Papanicolaou was born in the seaport town of Kymi, on the Greek island of Euboea, on May 13, 1883. He entered medical school to please his father, Nicholas, who was a physician, and the mayor of their town. He graduated medical school in 1904. In 1906, after completing military service obligations, he joined the family practice, but was more inclined to scientific research.