Apr 6, 2018

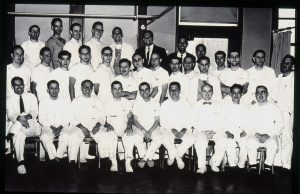

The photograph above shows the house staff of the Beth Israel Hospital in 1913. By that year, Beth Israel had been active for 24 years, and since 1902 it had been located on Jefferson & Cherry Streets, where this photograph was taken. (The hospital moved to its current location on Stuyvesant Square in 1929.) Although Beth Israel was still a relatively young hospital, it was already a state-of-the-art medical facility, with modern operating rooms, a radiology department, and laboratories for pathology and physiological chemistry. The hospital had a house staff, the precursor of the modern residency system, on which recent medical school graduates would spend two years living at the hospital and acquiring clinical experience.

When the Aufses Archives first acquired this photograph, the identity of the woman standing in the back row was unknown. There were two prints of the photograph in the collection, and they were labeled with conflicting dates, neither of which seemed correct. One print was labeled 1929, but this could not be right, since the clothing appeared wrong for that date and the photograph was clearly taken at the Jefferson Street location. Another was labeled 1908, but in this case, who could the woman have been? The earliest known female doctor associated with Beth Israel was Nettie Shapiro, MD, who served a one-year term as a non-resident extern in 1909, but a comparison with other photographs of Dr. Shapiro showed that it wasn’t her.

The identity of the woman in the photograph remained a mystery until recently, when we discovered a newspaper article in a collection of clippings that provided the answer. The woman in the photograph is Sophie Rabinoff, MD, who was the first female member of the Beth Israel house staff. Born in Russia in 1889, the same year Beth Israel was founded, Dr. Rabinoff came to the United States as a baby with her immigrant parents. She grew up in New York City, where she attended Hunter College before receiving her MD degree from the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia.

Like other female medical students of her time, in addition to the challenge of mastering the med school curriculum, Dr. Rabinoff had to overcome prejudice against women to continue pursuing a medical career. As the article describes, before taking the competitive examination for the Beth Israel house staff, she had to persuade the hospital management to allow her to sit for the exam. It was only after she came in first out of 31 candidates, ahead of 30 men who also took that year’s examination, that she was admitted. Unlike her predecessor Dr. Shapiro, who as an extern did not live in the hospital or serve the full two-year term, Dr. Rabinoff became a full member of the house staff, with all the accompanying responsibilities and privileges. Unfortunately, 1913 is one of the few years for which the Aufses Archives does not have the minutes of Beth Israel’s trustees or medical board, so we have no record of the debates that might have accompanied her admission.

The photograph in the newspaper article was clearly the same person as the woman in the photograph, confirming that this was an image of Dr. Rabinoff and the rest of the 1913 house staff. A search for additional information on Dr. Rabinoff revealed that she went on to a distinguished career in public health, as documented by her entry in the Jewish Women’s Archive Encyclopedia. After her time at Beth Israel, Dr. Rabinoff served with a Hadassah medical mission in Palestine before returning to New York and becoming a public health officer. She worked for two decades for the Department of Health, where she was responsible for overseeing public health programs in various parts of Manhattan and the Bronx, before joining the faculty of the New York Medical College in 1939. At her passing in 1957, she had recently retired as Director of the College’s Department of Public Health and Industrial Medicine.

Mar 23, 2018

A new finding aid for The Col. Henry H. M. Lyle Collection of World War I Photographs and Documents, 1916-1943, was recently published and made available to researchers on-line (http://icahn.mssm.edu/about/ait/archives/collection/henry-lyle). The collection includes 200 photographs from World War I, maps and documents used during the war, some correspondence, and reprints of articles by Lyle.

A new finding aid for The Col. Henry H. M. Lyle Collection of World War I Photographs and Documents, 1916-1943, was recently published and made available to researchers on-line (http://icahn.mssm.edu/about/ait/archives/collection/henry-lyle). The collection includes 200 photographs from World War I, maps and documents used during the war, some correspondence, and reprints of articles by Lyle.

The heart of the collection is the photographs taken in France during World War I, which depict often dramatic or surprising images of the war. There are views of hospital stations, barracks, and outdoor equipment (some include large defensive weapons), transportation of wounded soldiers, field dressing stations, supply trains, and troops on the battlefields. Interior views document soldiers, patients, operating rooms and special treatment rooms. A number of the images display the effects of mustard gas and other brutal wounds sustained by soldiers, while others capture the unit compound against the French countryside in an oddly artistic fashion. Still others provide a view of everyday life in the compound – washing clothes, unloading shipments of supplies and such, but which brings to life the challenges of a large group of people living in one spot at that point in time. Laundry meant picking lice off of clothes; unloading supplies meant huge piles of boxes; transporting wounded soldiers sometimes meant walking through ankle-deep mud. The collection also captures images of foreign soldiers in national uniforms, some riding horseback, a lifestyle that is very different from the standard U.S. soldier’s, which adds an interesting, and occasionally humorous, side to the war.

Henry Hamilton Moore Lyle, MD, was a noted surgeon and decorated soldier. He was born in Northern Ireland in 1874. His family immigrated to Ontario, Canada when Lyle was a boy. He graduated Cornell in 1896, and went on to Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, graduating in 1900. He took an internship at St. Mary’s Hospital for Children and at New York Hospital and a year’s surgical internship at St. Luke’s Hospital (1901-1902) before joining St. Luke’s surgical staff in 1904 and where he remained on staff until his death.

It appears that Lyle spent the year between his internship and surgical appointment traveling abroad, visiting clinics in Great Britain, France and the German-speaking countries. This familiarity with Europe may have led to his voluntary enlistment in World War I two years before the U.S. was formally involved in the conflict. In 1915 he took leave from his private practice and hospital positions in New York and spent six months as Chief Medical Officer of American Ambulance Hospital B, Juilly, France.

In 1916 he again took a leave and returned to France to serve for several months as Chief Surgeon of Ambulance d’Annel (Longueil, France). In April 1917 when the US entered the conflict, he joined the U.S. Army Reserve and in May was ordered to active service. In June he organized the United States Army Evacuation Hospital No. 2 at Camp Benjamin Harrison, and was appointed its commander when it left for France in January 1918.

In September 1918, Lyle was made Director of Ambulances and Evacuation of the Wounded for the First Army. During the ensuing Meuse-Argonne offensive, over 125,000 sick and wounded were brought to the railhead hospitals under his supervision. In recognition of his outstanding service, particularly during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, where the Evacuation Hospital No. 2 played a major role as one of two front line hospitals established in the Zone of Combat, he was decorated with the Distinguished Service Medal (U.S.). Lyle was also awarded the British War Medal and the British Victory Medal.

When the war ended Lyle returned to New York and medical practice at St. Luke’s Hospital, where his reputation as an outstanding surgeon followed his successes in battle. Lyle retired from medical practice in 1938, though remained a Consulting Surgeon at St. Luke’s until his death from coronary thrombosis on March 11, 1947.

Feb 21, 2018

Soon the Match will be upon the fourth year class and after months of deciding on a field, debating on various institutions, filling out paperwork and then smiling bravely through interviews, the new doctors will be on the resident staff of a hospital. This complex system of ‘matchmaking’ began in 1952 and replaced the practice of individuals applying to various residency programs, perhaps being measured against changeable and very subjective criteria.

In the early years of the 20th century, The Mount Sinai Hospital had in place a rigorous testing program to help winnow the number of applicants, leaving the ‘best and the brightest’ to face additional testing. Each year several hundred medical students would sit for the examinations that would lead to the selection of the twelve newest members of the house staff. The first day’s written examination was number coded, with the individuals’ names hidden so favoritism could not occur. The next day, the top scores were posted, and the 60 highest scorers would return for oral exams given by the medical staff. The questions were broad and usually designed to show a wide knowledge in the basic sciences and clinical medicine, as well as critical thinking skills. Questions on art or literature were not unknown, depending on the faculty member’s interests. The exam evolved over time to be more rigorous, and eventually recommendations from medical schools deans were also sought.

In 1930, these were some of the written questions the applicants were posed. How would you do?

1. In what stages of the following diseases would you terminate early pregnancy? a. Tuberculosis of the lungs b. Nephritisc. Diabetes d. Valvular heart disease

2. Under what conditions would you select for anesthesia? a. Chloroform b. Ether c. Nitrous oxide d. Spinal e. Local f. What special contra-indication for each?

3. In what illnesses may the joints be involved?

4. In what extra abdominal conditions may abdominal symptoms appear?

5. A patient has been operated upon for an acute gangrenous appendicitis with abscess. He had one chill prior to operation. Post-operative course is marked by fever of 102 to 104; high leucocytosis; polynucleosis. X-ray examination of the chest and right hypochondrium shows moderate elevation of right diaphragm. Discuss possible causes of the high temperature.

Jan 16, 2018

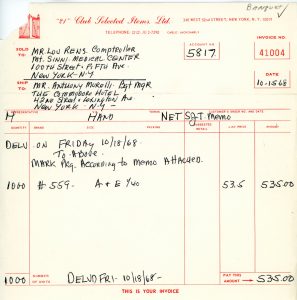

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Classes began on September 9th, and on October 20, 1968 there was a day-long celebration to dedicate the School and inaugurate Dean George James, MD as the first President of The Mount Sinai Medical Center. As part of this special day, there was a colloquium in the morning with four Nobel Prize laureates speaking about the future of medicine. (The papers presented by the speakers were later published in the Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. They are available here.) In the afternoon there was the dedication of the School and the inauguration of Dr. James. In the evening there was a banquet held at the Grand Ballroom at the Hotel Commodore.

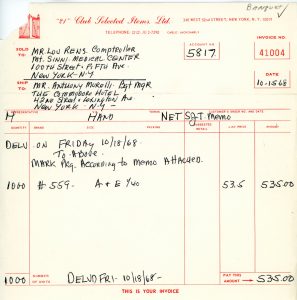

Cigar order for the Dedication Day banquet

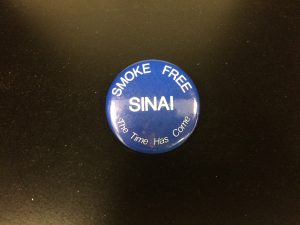

The Aufses Archives has several files about the planning and creation of this big event and how it all came together over a few short months. No detail was too small for the organizers to organize, as evidenced by an invoice for 1,000 cigars to be sent to the hotel from the 21 Club (founded by the brother of Mount Sinai Trustee I. Robert Kriendler). Today we would be shocked if a hospital passed out tobacco products but the 1960s were a different time. Still, already the tide was turning. In March of 1968, the Trustees’ Executive Committee had voted 8 to 5 to ban the sale of cigarettes at Mount Sinai, but it was not until 1989 that areas of the Hospital started to be designated as smoke free. This was the result of action by the Student Council of the School, with the support of the Dean’s Office, and then working with the Hospital administration and the Medical Board. What was seen by some at the time as difficult to implement is now viewed as a simple idea whose ‘time had come.’

A button created by Mount Sinai students to encourage the institution to go smoke free, 1989

Dec 8, 2017

In October of this year, The Mount Sinai Hospital announced the opening of the new cardiac unit, the former Cardiac Care Unit (CCU), now located on KCC 6 in the Klingenstein Clinical Center. There are 20 beds, ten of which are the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (CICU) and ten are step-down beds, the Cardiac Step Down Unit (CSDU). Unlike the other ICU units, the ten ICU beds are all private rooms. The entire unit is beautiful, with a receptionist desk as you get off the elevator.

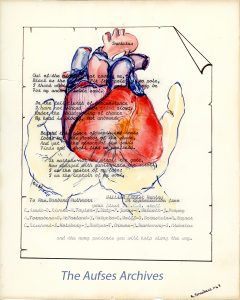

It just so happens that last year, the Aufses Archives received a small set of papers from Barbara McPeek Mulhearn, RN, Class of 1962 of The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing. Among those items was information about Mulhearn’s role in creating the first Cardiac Care ICU at the Hospital, which opened in 1968. Her title was Assistant Nursing Supervisor in charge of the Ames Coronary ICU, an eight bed unit on the 4th floor of KCC. The Unit opened February 19, 1968.

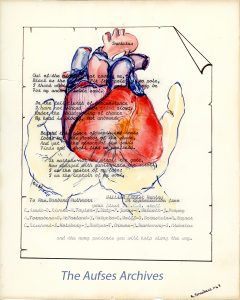

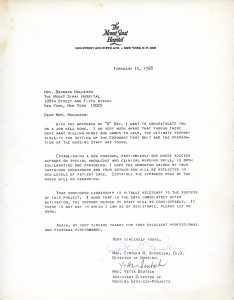

Shown below are two pieces from the collection: a drawing of a heart held in a person’s hands with the poem “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley typed over it. This was sent to Mulhearn from “her first I.C.C.U. staff,” in appreciation from them “and the many patients you will help along the way.” Also shown here is a letter from Dr. Cynthia Kinsella, the Director of Nursing at The Mount Sinai Hospital at the time, thanking Mulhearn for her efforts and encouraging her as they neared the Unit opening.

Fifty years on, the caring legacy continues.

Sep 29, 2017

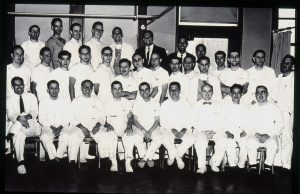

As the repository for the historical records of the seven Mount Sinai Health System hospitals, the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives has an extensive collection of historical photographs, many of which are available to view in our Image Database. Sometimes, however, the photographs in our collection have no information that would give them context. These photographs of the Beth Israel Medical Center house staff in the 1950s and 1960s arrived at the Archives as part of an unorganized collection of slides that we have been hard at work arranging and cataloging. While we can tell that they are photographs of the house staff, and can recognize that most of them were taken on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion, we don’t know the names of any of the doctors. Do you? If so, contact the Archives and let us know!

The 1958 Beth Israel house staff on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion

The 1958 Beth Israel house staff on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion

The Beth Israel house staff of an unidentified year (early 1960s?) on a hospital ward

The Beth Israel house staff of an unidentified year (early 1960s?) on a hospital ward

The Beth Israel house staff of an unidentified year (late 1950s?) on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion

The Beth Israel house staff of an unidentified year (late 1950s?) on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion

The Beth Israel house staff of an unidentified year (early 1960s?) and other Beth Israel doctors/administrators on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion

The Beth Israel house staff of an unidentified year (early 1960s?) and other Beth Israel doctors/administrators on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion