“He is looking for notoriety”: Dr. M.J.B. Messemer, Celebrity Coroner

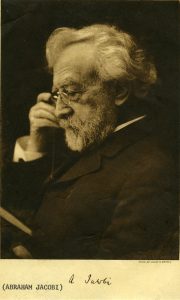

The Aufses Archives recently announced the opening of a new digital collection of letters to and from Abraham Jacobi, MD, the “father of American pediatrics” and a towering figure in the history both of Mount Sinai and of nineteenth-century American medicine. The letters, most of which deal with the staffing and administration of Mount Sinai’s outpatient clinics, contain the historical traces of many other physicians and surgeons who passed through Mount Sinai in the late nineteenth century. Some went on to quiet careers in private practice; others were famous in their time but have since been forgotten.

One letter in the collection, dated March 1st, 1879, contains an update from Rudolf Tauszky, MD, Secretary of the Medical Staff of the Out-Door Department (that is, the outpatient clinics), informing Dr. Jacobi of changing staff assignments. Among other changes to the roster, Doctors M.J. and E.J. Messemer had been appointed to the internal medicine clinic.

These forgotten names piqued our curiosity. Who were they? How were they related? Research confirmed that the Messemers were brothers and had graduated from Bellevue Hospital Medical College (predecessor of today’s NYU School of Medicine) a few years previously. At a time when the modern system of clinical instruction was still in its infancy, positions in the charity outpatient clinics of a prestigious hospital were a valuable way for recent graduates to gain practical experience on the way to establishing a private practice.

Further research revealed the subsequent career of Michael Jean Baptiste (M.J.B.) Messemer, MD. He turned out to have been a colorful figure who was a minor celebrity in old New York.

New York Tribune, May 27, 1891

New York Tribune, May 27, 1891

New York City in the late nineteenth century was limited to Manhattan and a portion of what is now the South Bronx, and city politics were firmly under the control of Tammany Hall, of which Dr. Messemer was a loyal member. Today, the Chief Medical Examiner of New York City is a highly regarded professional, but in the 1880s the position of City Coroner was considered a “plum” job for Tammany loyalists whose incumbents could draw a high salary with relatively little work. Dr. Messemer became one of the city’s four coroners in 1883. One colleague, Coroner Levy, charged Messemer with spending much of his time in recreational travel, pleading sickness rather than attending to his public duties. Levy remarked sarcastically to a New York Tribune reporter that “I am afraid that the public is skeptical about him.”

New York Times, December 10, 1885

New York Times, December 10, 1885

Dr. Messemer did investigate cases, however. Many of these were widely reported in the popular press, leading to accusations that Dr. Messemer was publicity-hungry and using the office of coroner to promote himself. In 1885, on the death of railroad magnate William Henry Vanderbilt, Messemer rushed to Vanderbilt’s mansion in the company of a reporter to inspect the body for foul play. A colleague accused him of “looking for notoriety,” adding that such an uninvited inspection was “wrong and uncalled for” under the Police Department rules governing suspicious deaths.

Dr. Messemer passed away in 1894 while traveling in Europe. The “widely known New Yorker,” wrote the obituary columnist of the New York World, “was ever willing to help his friends among newspaper men get news, and thereby get notoriety for himself. To-day Messemer furnishes another and a last story.” The will that Dr. Messemer had placed on file in New York left his entire estate to his brother, but his European mistress claimed he had written her into his will on his deathbed. Although she traveled to New York to contest the will in person, the suit was eventually settled in favor of his brother.