Apr 27, 2021

The Mount Sinai Hospital created its Dispensary/Out Patient Department in 1875 when it established four clinics: the Gynecology Clinic, the Children’s Clinic, as well as ones for Medicine and Surgery. Then as now, these clinics were designed to treat people with health needs that did not require a hospital stay. The Hospital traditionally had a long waiting list for admission, and this was seen as a way to help those they could before their conditions worsened. (In addition, in 1884, Mount Sinai Hospital created what it called the “Outdoor Visiting Physicians” to actually go to people’s homes to care for them there. Medicines were provided from the Hospital pharmacy.)

The Hospital was a charity organization and highly dependent on keeping costs down and maximizing donations to support its work. While there were a few patients willing and able to pay something for their care, the vast majority were treated free of charge both on the in-patient side as well as in the Dispensary. Since funds were so limited, Mount Sinai tried to take steps to ensure that their efforts were helping those most in need. One of those steps was to post a sign in the Dispensary that said, “Poor People Only Treated Here”. It eventually became clear that this sign was disrespectful to the people who used the clinic, and 140 years ago, on May 8, 1881, the Board of Directors of the Hospital decided to look into having the sign removed. Unfortunately, the Board minutes do not tell us if it was actually taken down.

The need to closely watch expenditures and try to reserve their services for the most needy continued to plague the Hospital leaders for decades. The beginnings of health insurance in the early decades of the 20th century helped, but it was really the implementation of Medicare and Medicaid in the mid-1960s that relieved hospitals of much of the burden of the costs of charity care.

The entrance to the MSH Dispensary, 1890

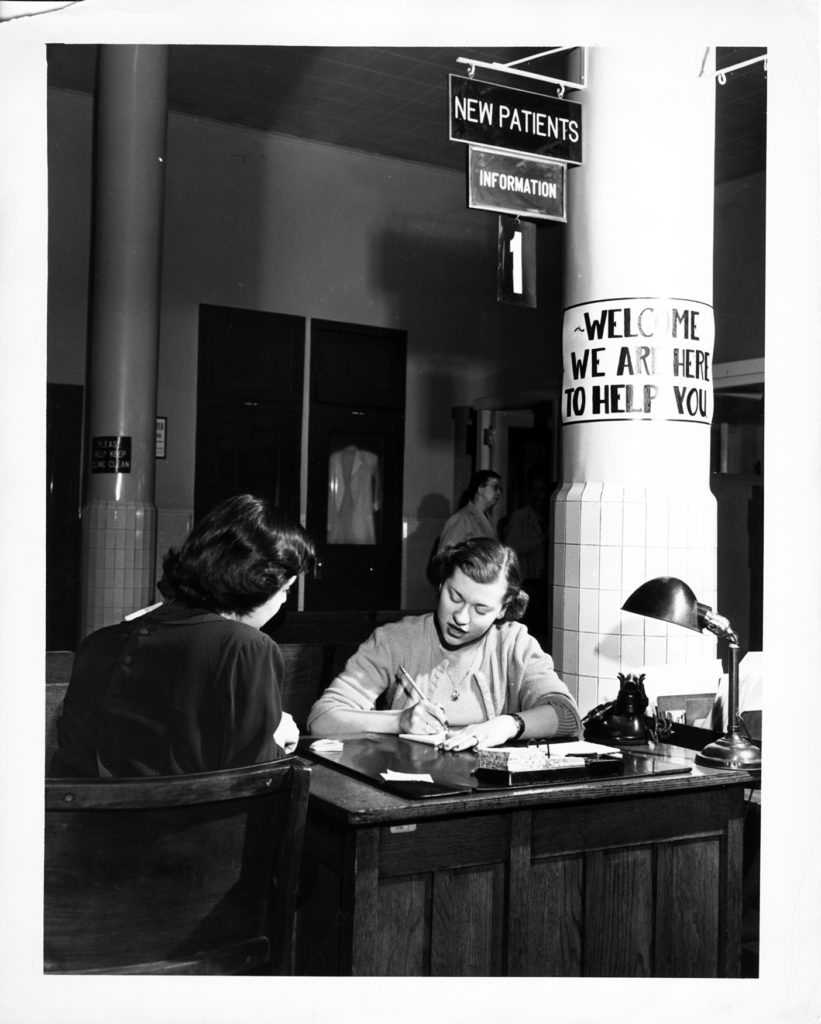

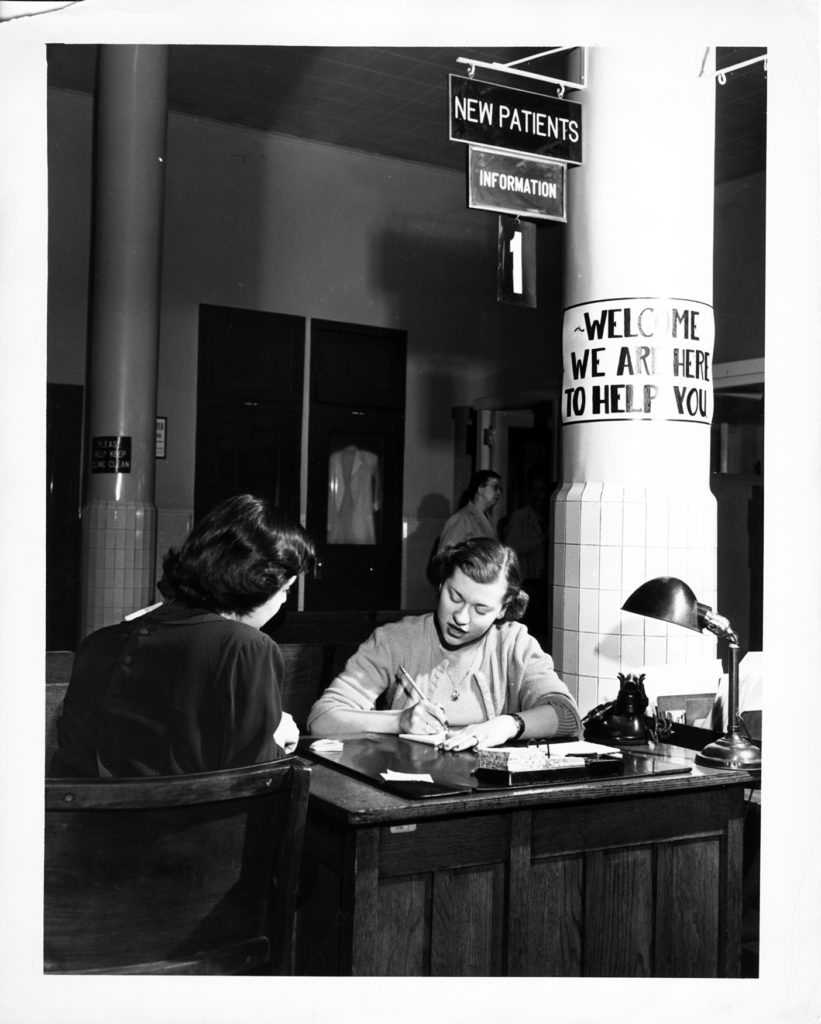

The Mount Sinai Hospital OPD Admissions desk in 1951

Apr 12, 2021

In today’s world, the only way to check into a hospital, without an emergency, is for a doctor to arrange for some kind of test or surgical procedure. But in the 19th century, hospitals functioned a bit like today’s walk-in clinics, at least in regards to admission. A person could come to the Hospital, speak with the Admitting Physician and request treatment for ‘X’ problem. But there were rules governing who would be accepted or refused.

By 1859, St. Luke’s published the first of their annual reports, which included reports from the Board President, The Pastor/Superintendent and the House Staff, along with lists of donations, occupations and diseases of those treated, and the publication of rules – for staff for patients and for visitors, and for Admission. Admission rules separated out patients with certain diseases. Those with contagious diseases were refused admission – this was a common practice for private hospitals at this time. The 1904 annual report is the first year the Hospital reported which applications were declined under the Rules of Admission, and their numbers. Ten persons were declined admission due to contagions like Erysipelas, scarlet fever and scabies.

Another group – the chronic or incurable – included paralytics, rheumatics, the mentally ill, incurable cancer patients, and those with an opium habit or delirium tremens, where also refused admission. Chronic cases in acute attack might be accepted, but were discharged once they returned to the ordinary health of one in that condition. Incurable cases might be admitted, but “only at the discretion of the Executive Committee of the Hospital.” These were also probably discharged as soon as they regained what was ordinary health for that condition. In 1904, 128 cases were refused admission to St. Luke’s for one of these reasons.

One exception to the rules was pulmonary consumptives (tuberculosis). In the 19th century, consumption was considered a hereditary disease, rather than a contagious one. The 1859 report of the Board of Managers, explains, “To provide for the incurably ill, particularly of this class, was one of the objects of the Hospital, and therein to supply an urgent want in the community… there was no resort for consumptives, so numerous in our climate, that St. Luke’s, as a church institution, felt bound to open to them her doors.“

The woman’s tuberculosis ward at St. Luke’s Hospital, circa 1900

The Pastor’s report often notes the comfort, and at times cure, these patients received, and their expressions of gratitude. In 1891, nine years after the discovery of the tubercle bacillus by Dr. Robert Koch, St. Luke’s accepted control over the House of Rest for Consumptives in the Tremont section of the Bronx, eventually moving all its patients to the main hospital and selling the property to support their care. Throughout the years annual reports note that consumptives made up to a quarter of the total census of patients in any given year.

These rules on admission disappeared early in the 20th century as hospitals’ ability to recognize and control germs was established, and as out-patient clinics opened to treat patients that might not have been admitted to the Hospital’s care in prior years.