Aug 31, 2021

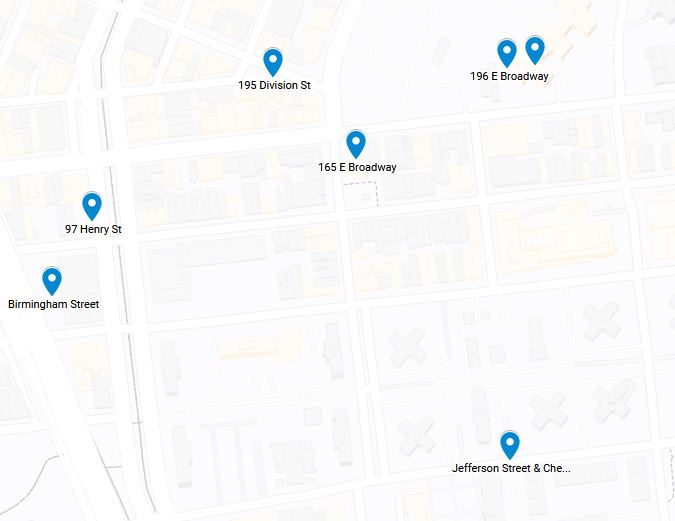

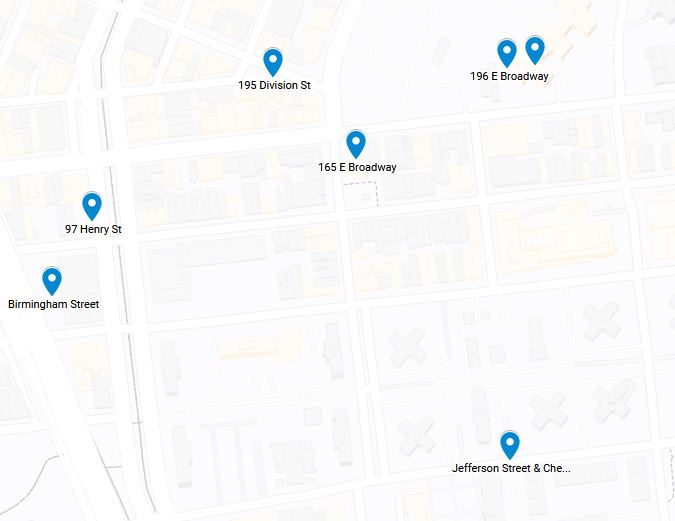

The first meeting related to the founding of Beth Israel Hospital was held on December 1, 1889 at 165 East Broadway. Healthcare was greatly needed in New York’s Lower East Side, whose residents, largely recent Jewish immigrants, were affected by poverty, close living quarters, and dangerous working conditions. From a 1901 essay on early Beth Israel history:

“The origin of the idea of this institution sprang from the poor themselves. So urgent was the need for such a local hospital, that in spite of the lack of support, and even of the discouragement of those in position to assume such a task, the poor themselves, by taxing their hard earned [sic] wages, gained by the sweat of their brows, established the association and undertook to support the Hospital…It serves to demonstrate the noble Jewish heart. These workingmen when they could earn their bread and butter were willing to contribute their 25 cents a month to help their neighbors in distress.”

In the face of “meagre [sic] and uncertain support,” the founders first endeavored to begin a dispensary, rather than a full-scale hospital, and in May 1890, rented a loft in a factory on Birmingham Street. (This street no longer exists, but today would be between Henry Street and Madison Street, just underneath the Manhattan Bridge.) The building was described as “most unsuitable and the accommodations about as poor as can be imagined” but still attracted more patients than could be treated, speaking to the great need for medical care in this neighborhood at the time.

Click here for an interactive map of Beth Israel historical locations

After two months at the Birmingham Street location, the Beth Israel outpatient dispensary moved to 97 Henry Street in July 1890. Described as an “old-fashioned parlor floor,” it was “much better situated” and the dispensary remained there for ten months.

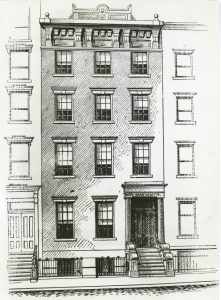

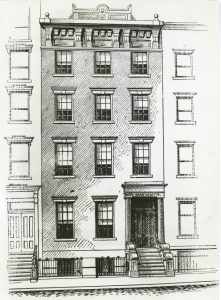

Sketch of the 206 E Broadway location of Beth Israel Hospital, circa 1892-1902.

In May 1891, Beth Israel moved to 196 East Broadway. With twenty beds, this is the first Beth Israel location to include inpatient services in addition to the outpatient dispensary. The hospital includes two house staff: Abraham Hymanson, MD, is the first House Physician, and Wolfgang Kaplan, MD is Assistant House Physician.

Embroiled in a financial crisis, Beth Israel moves again in May 1892, splitting their services across buildings at 206 East Broadway and 195 Division Street. With lower rent and more space, including thirty-four beds, Beth Israel was financially solvent for the first time. The Division Street building was renovated one floor at a time for inpatient and outpatient use.

Beth Israel Hospital remained in this location for over a decade, before moving to its location at Jefferson and Cherry Streets in 1902, and finally its current location at the Dazian Pavillion in Stuyvesant Square in 1929. The history of both of these Beth Israel Hospital locations will be addressed in future posts.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Aug 18, 2021

The Upper East Side home of The Mount Sinai Hospital and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai spans continuously from 101st St down to 98th Street, with other buildings arrayed nearby. To achieve this continuous campus, what had once been 99th and 100th Streets between Madison and Fifth Avenues have disappeared. How and when did that happen?

View along 100th St., around 1937

The Mount Sinai Hospital moved to 100th Street in 1904, taking up the whole block between the avenues and up to 101st Street. In 1911, the Hospital started buying lots on the south side of 100th Street in anticipation of a large expansion program. By 1921, those new buildings stretched from Fifth Avenue across but not quite to the end of 100th Street. The street was used for physician parking, and in December 1949, New York City deeded the bed of 100th Street to Mount Sinai. It continued as parking for a few more decades, but with the construction of the Guggenheim Pavilion starting in 1986, the street disappeared into a plaza between the original buildings and the new.

The story on 99th Street is very similar: Mount Sinai had expanded to having buildings spread along the northern side of the block. At the end of the 1950s, when construction of the Klingenstein Clinical Center (KCC), fronting onto the corner of Madison and 99th Street, was being planned, Mount Sinai sought the help of the City, and in August 1958, the road bed of 99th Street was deeded to Mount Sinai.

And what about the former streets? Once the construction on KCC was finished, this area became known as the Hospital Gardens, and graduation ceremonies for our School of Nursing, as well as special events were held out there. The plaza across 100th Street was covered in bricks, and a large sculpture called La Sfera Grande by Arnaldo Pomodoro was placed there in 1974. In the late 1960s, all of the buildings along the former southern side of 100th Street and the northern side of 99th Street were torn down to make way for the Annenberg Building. The Gardens became Ross Park, and today the Sfera Grande sits adjacent to the Nathan Cummings Atrium in the Guggenheim Pavilion. This is only appropriate since Mr. Cummings had originally given Mount Sinai the sculpture.

Nursing School graduation in the ‘Gardens’ in 1961. Note that KCC is being built in the back left of the image.

Aug 3, 2021

On August 27th, it will be 165 years since the first baby was born at The Mount Sinai Hospital in 1856. The mother was a Mrs. Lichtenstein. She named the baby Isaac Touro, in honor of a Hospital benefactor, Judah Touro (1775-1854), who had helped support the young Jews’ Hospital in New York, as Mount Sinai was then known. (Judah Touro also gave money for the founding of Touro Infirmary in New Orleans and today’s Touro College and University System is named for Judah and his father Isaac.)

Isaac Touro Lichtenstein was one of two babies born in the Hospital during its first year of operation. Until the 1920s, most babies were born at home or in one of the specialized women and child care hospitals around the City. This meant that many general hospitals, including Mount Sinai, never felt the need to add a formal obstetrical service to their offerings, thus limiting the number of babies born at the hospital over the years.

By the 1920s, as hospital births began to rise around the country, the Mount Sinai medical staff started to talk to the Board of Trustees about adding obstetrics. As the doctors saw it, the problems arising from not having babies born at the Hospital were: the Gynecology staff could not admit their obstetrical patients to Mount Sinai; there was no obstetrical training for the GYN residents, nor was there training for the pediatrics residents in newborn care. The last also applied to The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing, which affiliated with the Sloane Hospital for Women so students could fill the gap in their education.

While the Trustees were increasingly sympathetic with the request to add an obstetrical service, it wasn’t until the middle of the 1940s that concrete plans were made for the erection of a new building to house obstetrics and gynecology, today’s Klingenstein Pavilion on Fifth Avenue. Every new building demands a fundraising campaign to make it a reality. Mount Sinai had just finished a major expansion that ended in 1922, with the addition of a new School of Nursing building and a semi-private pavilion seen as the next priorities. When these two buildings opened, the Depression was in full swing, which sapped Hospital and potential donor resources. This was followed quickly by World War II, but by the mid-1940s, the Hospital could see a window of opportunity on the horizon.

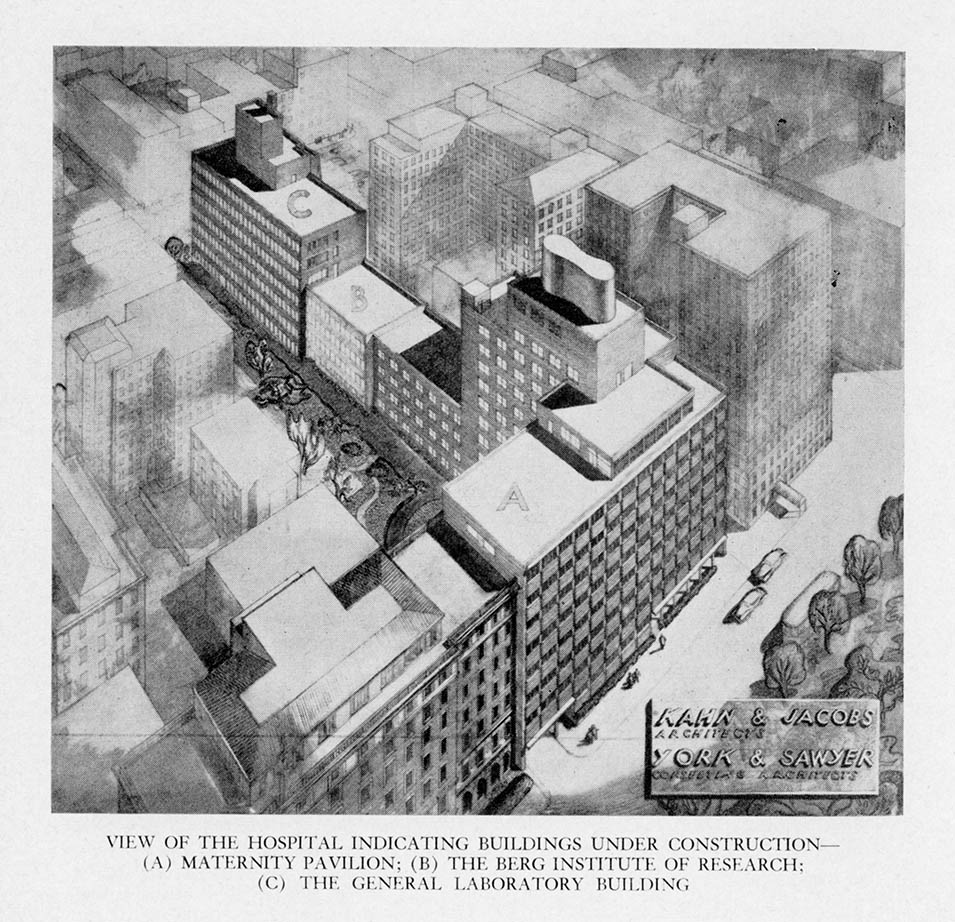

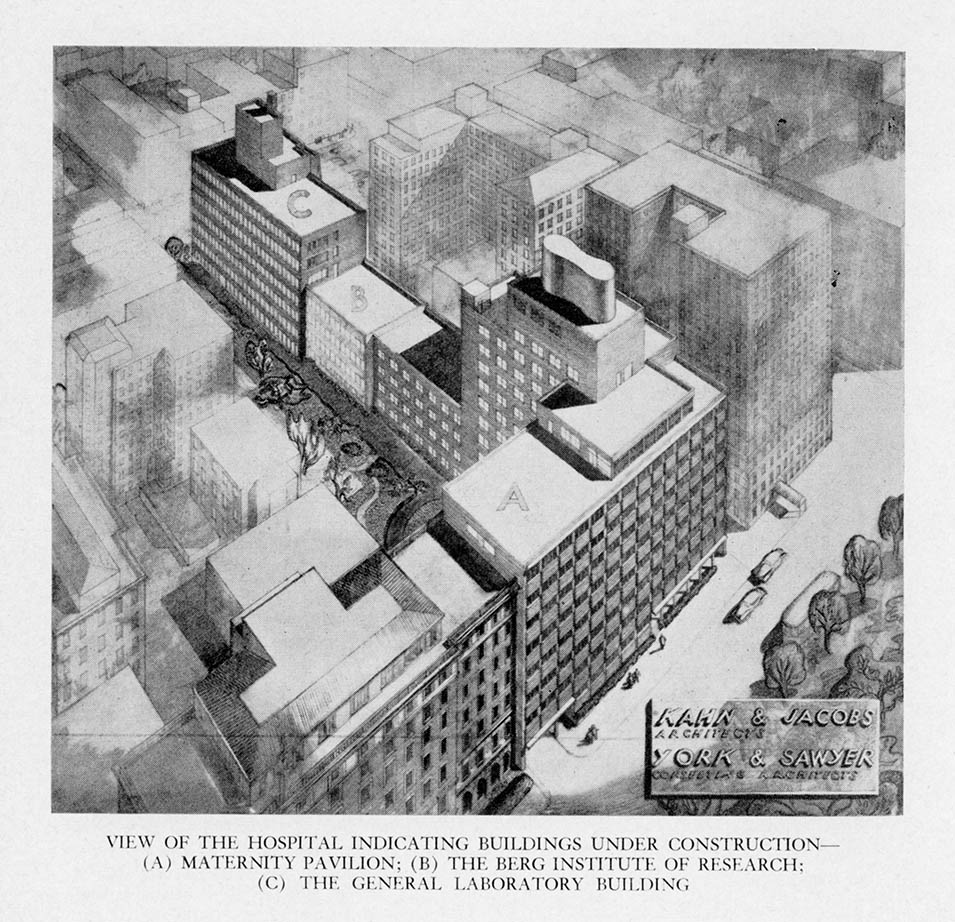

A fundraising campaign was begun when the war ended and on July 22, 1948, ground was broken for three buildings: the Klingenstein Pavilion, and the Atran and Berg Laboratories. In 1952, the obstetrical service started to operate as the building slowly opened. July marked the start of Mount Sinai’s first Prenatal Clinic, and the first prenatal clinic for women with diabetes in New York City started in the fall. The first OB patients were admitted in October, with the first baby born October 29, 1952 – 96 years after Isaac Touro Lichtenstein.

Jun 21, 2021

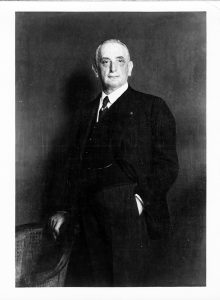

I recently spent some time reviewing the President’s Report section of the Annual Report of The Mount Sinai Hospital from 1921 (linked here, starting on page 190). The President then was George Blumenthal, a devoted trustee, and a smart businessman who had recently guided the Hospital through a major expansion program, the uncertainties of World War I, and the influenza epidemic of 1918. Reading the report reminded me of the joys – and problems – with reading primary historical sources: it is very easy in hindsight to see connections between two times that may not be related, and simple observations can seem very prescient.

Don’t get me wrong, parts of the report are very dated and irrelevant to today: the Hospital was unable to afford radium to use in patient treatment, and so that service was not provided. There was also a section on issues related to fund raising through the Federation of Jewish Charities (today’s UJA-Federation). But still, there were many issues that would seem familiar to our current leaders. The Hospital was perennially short of money, but after the epidemic and the war, wages were rising quickly for what today would be called “essential workers”. Adding to this was a restrictive immigration policy that limited the labor pool. The inability to hire as many trained nurses as they needed was a continuing struggle as well, something the whole country recognizes today.

George Blumenthal, President of The Mount Sinai Hospital from 1911-1938

And yet Blumenthal made the case – as we do today – for why private hospitals like Mount Sinai deserve the philanthropic support of the people. He says:

It is absolutely essential that private institutions like Mount Sinai should be leaders of progress in hospital work…. To discover, test and demonstrate new methods of treatment is recognized as one of the functions of private institutions and it is one of the strongest reasons for their existence and constitutes their most important claim on the generosity of the public which supports them.

A couple of pages later, Blumenthal makes a bold statement about the importance of Mount Sinai being a teaching hospital. At this time it had loose clinical ties to both Columbia and NYU. He envisioned something more:

A Hospital possessing the clinical and laboratory resources of Mount Sinai should have university affiliation or if this be impracticable should independently utilize its organization for teaching purposes, for in no other way can the fullest benefits be derived from the intensive study of interesting, varied and often perplexing clinical material. We hope the day is not very far off when work on these lines can be done either through affiliation with one of the many teaching institutions located in our city or by independent action.

And “independent action” it was. Even with academic affiliations with various medical schools, in the 1950s Mount Sinai was not satisfied that they were living up to their potential in terms of training the next generation of physician/scientists or using their immense clinical material for creating new medical knowledge to advance patient care. In 1963, the Trustees received a charter to create their own medical and graduate schools. The Mount Sinai School of Medicine opened in 1968.

Nov 9, 2020

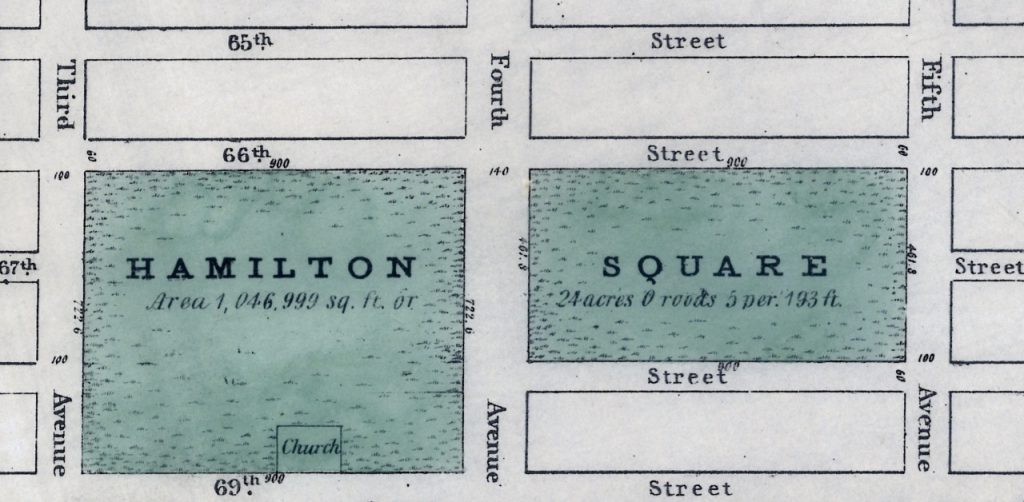

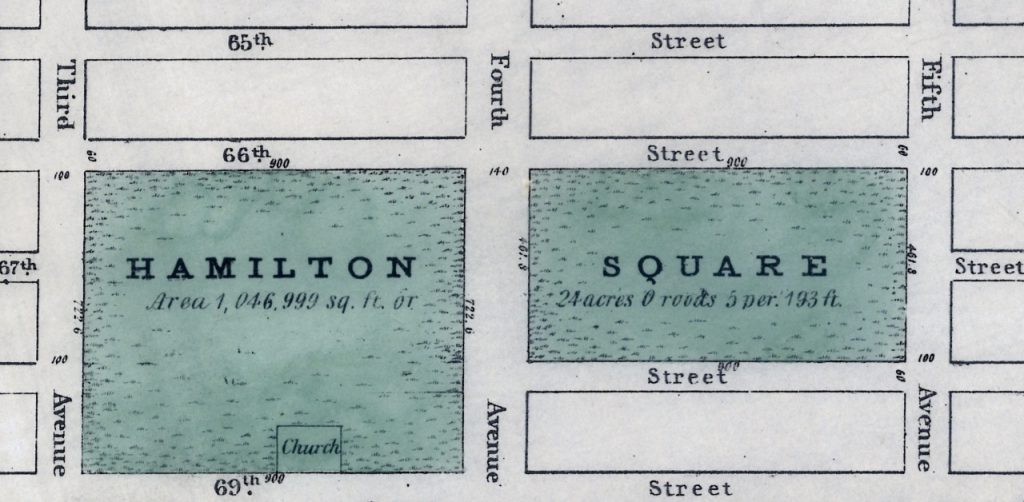

I recently read a piece about Hamilton Square in the Roosevelt Island Historical Society’s From the Archives email. This park, which was named for Alexander Hamilton, existed on the Upper East Side of Manhattan from around 1807-1869. I found this fascinating since The Mount Sinai Hospital moved to Lexington Ave. and 66th St. in 1872. I knew that the City had ‘seeded’ this area with non-profit entities: Hunter College, many hospitals and schools, but I had never heard about the Square itself, which ran from 66th to 69th Streets between 3rd and 5th Avenues. Finally, Mount Sinai had a Hamilton connection, even though he died in 1804, 48 years before the Hospital was created!

Map of Hamilton Square from the New-York Historical Society

When the Square was broken up, The Mount Sinai Hospital (MSH) was located on W. 28th Street, between 7th & 8th Avenues. It had been founded in 1852 as the Jews’ Hospital in the City of New York (the name was changed in 1866) and had opened its first building in 1855. After the Civil War, the leadership realized that the facility was inadequate and the location less than ideal due to the growth of the City. On November 2, 1867 the Directors authorized the purchase of ten lots of land from 65th to 66th Street on the west side of Park (then 4th) Ave. and later added eight more lots there. But then on October 6, 1868, the City leased Mount Sinai twelve lots of land between 66th and 67th on Lexington Ave. for $1 a year for 99 years. Somehow, over the interim, the City and Mount Sinai had reached an agreement on the Hospital taking over part of the former Hamilton Square. The earlier lots were later sold, saving Mount Sinai thousands of dollars. On May 25, 1870, the cornerstone for the second MSH was laid. The President of the Hospital, Benjamin Nathan, and Mayor Oakley Hall were there. (Within two months, Nathan was murdered in his bed on a ‘dark and stormy night.’)

On May 29, 1872, a dedication ceremony was held for the new Mount Sinai Hospital. When the building opened, it had a greatly expanded capacity of 110 beds. The building was designed by the well-known architect, Griffeth Thomas, and cost $335,000 to complete. It had an operating room in the basement of the north wards, rooms for our newly created House Staff to live in, a meeting room for the Directors, and a synagogue. Lexington Ave. remained unpaved for two more years, and the Hospital never wired the facility for electricity. A telephone was installed in 1882; the number was “Thirty-Ninth St., 257”. It was at this site that Mount Sinai transformed into what we would recognize as a modern hospital, with medical education and research joining its core mission of providing patient care.

In typical Mount Sinai fashion, this facility quickly became too small. Additional buildings were built and major renovations were begun in 1882. In 1890, Mount Sinai added a building across from the Hospital on the north side of 67th St. for our nursing school and Out Patient Department. This building is the only remnant of Mount Sinai that remains there today. It later served as the home of the Neurological Institute, the Polish legation, and finally became a school for the Archdiocese of NY. The Mount Sinai Hospital moved from Lexington Ave. in 1904 to its current East Side location on 100th St., between Madison and 5th Avenues. The name of Hamilton continues on various buildings and neighborhoods of the City, making its most recent appearance on Broadway.