Giving Birth to an Obstetrical Service

On August 27th, it will be 165 years since the first baby was born at The Mount Sinai Hospital in 1856. The mother was a Mrs. Lichtenstein. She named the baby Isaac Touro, in honor of a Hospital benefactor, Judah Touro (1775-1854), who had helped support the young Jews’ Hospital in New York, as Mount Sinai was then known. (Judah Touro also gave money for the founding of Touro Infirmary in New Orleans and today’s Touro College and University System is named for Judah and his father Isaac.)

Isaac Touro Lichtenstein was one of two babies born in the Hospital during its first year of operation. Until the 1920s, most babies were born at home or in one of the specialized women and child care hospitals around the City. This meant that many general hospitals, including Mount Sinai, never felt the need to add a formal obstetrical service to their offerings, thus limiting the number of babies born at the hospital over the years.

By the 1920s, as hospital births began to rise around the country, the Mount Sinai medical staff started to talk to the Board of Trustees about adding obstetrics. As the doctors saw it, the problems arising from not having babies born at the Hospital were: the Gynecology staff could not admit their obstetrical patients to Mount Sinai; there was no obstetrical training for the GYN residents, nor was there training for the pediatrics residents in newborn care. The last also applied to The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing, which affiliated with the Sloane Hospital for Women so students could fill the gap in their education.

While the Trustees were increasingly sympathetic with the request to add an obstetrical service, it wasn’t until the middle of the 1940s that concrete plans were made for the erection of a new building to house obstetrics and gynecology, today’s Klingenstein Pavilion on Fifth Avenue. Every new building demands a fundraising campaign to make it a reality. Mount Sinai had just finished a major expansion that ended in 1922, with the addition of a new School of Nursing building and a semi-private pavilion seen as the next priorities. When these two buildings opened, the Depression was in full swing, which sapped Hospital and potential donor resources. This was followed quickly by World War II, but by the mid-1940s, the Hospital could see a window of opportunity on the horizon.

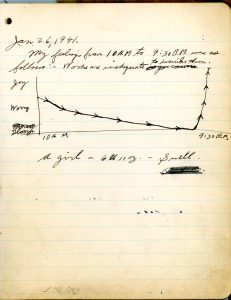

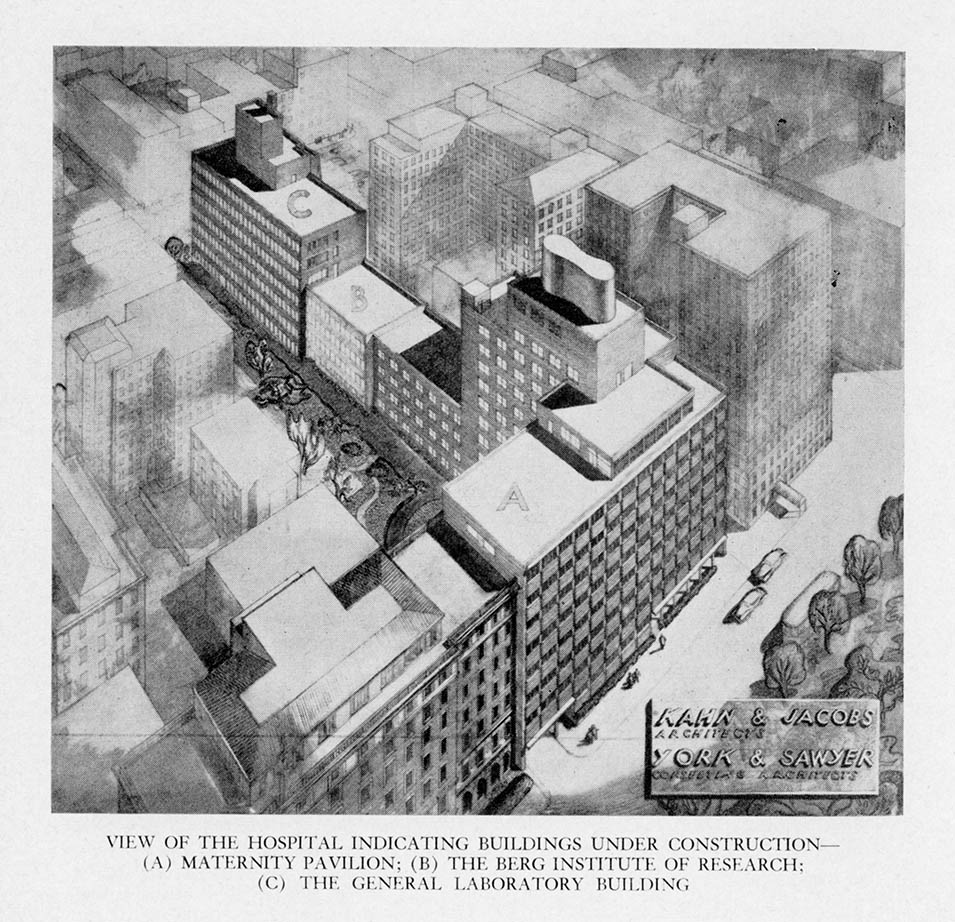

A fundraising campaign was begun when the war ended and on July 22, 1948, ground was broken for three buildings: the Klingenstein Pavilion, and the Atran and Berg Laboratories. In 1952, the obstetrical service started to operate as the building slowly opened. July marked the start of Mount Sinai’s first Prenatal Clinic, and the first prenatal clinic for women with diabetes in New York City started in the fall. The first OB patients were admitted in October, with the first baby born October 29, 1952 – 96 years after Isaac Touro Lichtenstein.