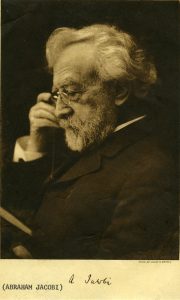

The Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives at Mount Sinai is proud to make available two groups of digitized correspondence to and from Abraham Jacobi, MD (1830-1919), the “father of American pediatrics.” Dr. Jacobi was a towering figure both at Mount Sinai, where he chaired the Medical Board for twenty-five years and is the namesake of the Alumni Association’s Jacobi Medallion, and in the broader world of the history of medicine. He was the first Professor of Pediatrics at an American medical school (beginning at New York Medical College and later moving to Columbia), and under his leadership Mount Sinai created the first department of pediatrics at a general hospital in New York City.

This digitized collection is the work of two institutions, the Aufses Archives and the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, which generously made available scanned images of their own collection of Jacobi correspondence. By bringing together two geographically separated collections whose contents overlap in time and subject matter, this digitization project, which includes full transcriptions of all manuscripts, makes Dr. Jacobi’s story more accessible to scholars and the general public. The Mount Sinai letters are available here, and the Historical Medical Library’s letters are available here.

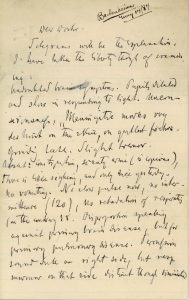

Although the majority of the collection deals with the staffing and administration of The Mount Sinai Hospital and its Out-Door Department (the outpatient clinics), one letter in the collection provides a fascinating glimpse into Dr. Jacobi’s medical practice. In 1884, at the request of an unidentified colleague, he examined an unnamed patient and replied with a brief but dense handwritten note describing his findings. Like modern physicians, Dr. Jacobi used close attention to his patient’s symptoms to perform a differential diagnosis. With no laboratories or high-tech equipment at his disposal, he relied solely on the evidence of his immediate senses, counting the pulse and percussing the chest to make a tentative diagnosis of secondary meningitis brought on by a pulmonary condition.

Dr. Jacobi comments that the “prognosis [is] bad, it is true — but still, who can tell?” His uncertainty tempered with hope reminds us that in hindsight, the decade of the 1880s was a pivotal time for modern medicine, when therapeutics had not yet caught up with rapid advances in accurate diagnosis. Nothing more is known of this patient or his eventual fate.