Nov 30, 2016

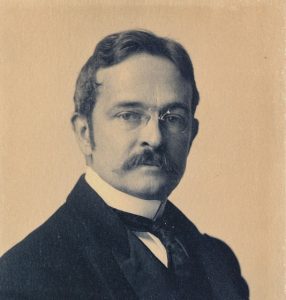

Robert Abbe (1851-1928) was a surgeon and pioneer radiologist in New York City. He was born in lower Manhattan and educated in NYC’s public schools. He attended the College of the City of New York (S.B., 1870) and Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons (M.D., 1874).

Abbe was best known as an innovative plastic surgeon, particularly for developing a procedure for repairing hair lip deformities (now commonly known as the Abbe Flap), and for  pioneering the use of radium as a treatment for various medical conditions. His many published articles document the breath of his surgical experience and the successes he had using radium to treat patients.

pioneering the use of radium as a treatment for various medical conditions. His many published articles document the breath of his surgical experience and the successes he had using radium to treat patients.

He served as a surgeon at the New York Hospital, St. Luke’s Hospital, Roosevelt Hospital, and the New York Babies Hospital, and was also a professor of surgery at the Women’s Medical College of New York, The New York Post-Graduate Medical College, and the College of Physicians and Surgeons.

In his free time, Abbe enjoyed drawing, painting oil portraits, and watercolors, and the emerging art of photography. During his later years he spent summers in Bar Harbor, Maine where he developed an interest in the Native American population of the area. He began collecting Native American tools and artifacts that he found in the area and in Stone Age relics he found on Mount Desert. He dreamt of creating a museum to display his extensive collection, and raised funds to do so. Unfortunately, he did not survive to see his dream fulfilled; the museum, which carries his name and still operates, opened a mere five months after his death of anemia at age 77, most likely due to handling radium.

A small collection of his papers and many reprints of his articles are open to researchers at the Mount Sinai Archives. The collection guide is available on the Archives web site, http://icahn.mssm.edu/about/ait/archives/collection/robert-abbe.

Nov 4, 2016

(This post was written by Nancy Mary Panella, Ph.D., Archivist Emeritus, St. Luke’s and Roosevelt Hospitals)

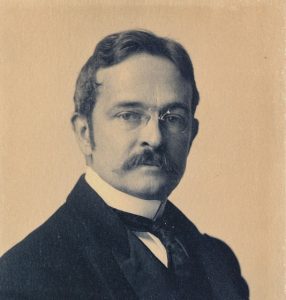

James Henry Roosevelt, whose bequest founded the Roosevelt Hospital, was the son of James Christopher Roosevelt (1770-1840) and Catherine Byvanck Roosevelt (1773-18??). He was also a distant cousin of President Theodore Roosevelt.

James H. Roosevelt

James Henry was born at his family’s home on Warren Street in lower Manhattan on November 10, 1800. Following his earlier education in neighborhood schools, he enrolled in Columbia College, where his studies included law, and was graduated from there in 1819. He subsequently set up a law practice in New York City.

With his studies behind him, and his law practice established, he stood on the threshold of a promising life: Described as a young man of pleasing appearance, brown hair, above-average height and with a gentle and courteous demeanor, he was well-to-do, brilliant, and engaged to be married to Julia Boardman, who was from an old New York City family.

But, suddenly, an illness that left him physically disabled struck, ending his plans for both career and marriage. The exact nature of the illness is unclear: Some speculated that it was lead poisoning from a home remedy for a cold, concocted of hot milk into which lead shot had been boiled. Others think he fell victim to poliomyelitis.

In any case, largely incapacitated, he abandoned his law practice. Not wanting to ‘burden’ Julia Boardman with his disability, he broke his engagement to her. (Neither married and both remained lifelong friends; in fact, one of the few bequests he made, outside of the one to his nephew, James C. Roosevelt Brown, and the monies left to found The Roosevelt Hospital, was an annuity for Ms. Boardman, whom he also named as executrix of his will.)

James Henry then embarked on a life not just of physical limitations, but also of frugality and austerity, devoting much of his time and interests to real estate dealings and to the management of his securities; he thus increased his worth substantially. It is thought that he conserved and increased his funds for one specific purpose: to support “the establishment in the City of New York of an [sic] hospital for the reception and relief of sick and diseased persons.” Whatever the reason, when he died in 1863, he left in excess of one million dollars toward that objective.

The hospital to be founded under the terms of his will was to be a voluntary hospital that cared for individuals regardless of their ability to pay. It seems reasonable to suppose that having himself suffered from illness, he realized the plight of those who might at the same time be afflicted with both sickness and destitution.

It is said that James Henry was never morose or gloomy. He maintained an active interest in the life about him and in the affairs in which he could not participate. He enjoyed the companionship of a host of friends, one of the closest being Julia Boardman.

Although James Henry Roosevelt’s remains were first buried in his family’s vault in the New York City Marble Cemetery, they were moved to the Roosevelt Hospital grounds when a monument to him was placed there in 1876. Moved twice again on the hospital grounds (hospital expansion required the moves), in late 1994 his remains were exhumed, and in the spring of 1995 re-interred in the New York City Marble Cemetery. Julia Boardman’s remains were interred in the same cemetery, but in her father’s vault.

Oct 18, 2016

New York Times, January 24, 1917

On October 16th, Planned Parenthood of New York reached its 100th anniversary. It grew from a small birth control clinic created in Brownsville, Brooklyn by Margaret Sanger, her sister Ethel Byrne, and Fania Mindell. At the clinic, they distributed birth control, as well as pregnancy planning advice and information. Even though the three women were arrested for distributing obscene material and jailed, their efforts led to changes in the law allowing for birth control and sex education in the years to come. In 1921, the clinic became the American Birth Control League, which changed its name to the Planned Parenthood Federation of America in 1942.

What does this have to do with Mount Sinai? Margaret Sanger and her younger sister, Ethel Byrne, were nurses. Mrs. Byrne graduated from The Mount Sinai Training School for Nurses in 1909. The sisters did not always get along, but they were united in the believe of women having the right to plan their families. Mrs. Byrne protested her sentence and her jail term of 30 days and launched a hunger strike, which brought a great deal of attention to their cause. The hunger strike lasted for five days, and then she was forcibly fed by prison doctors. Mrs. Sanger and women civic leaders, including Anne Van Kirk, the Superintendent of The Mount Sinai Hospital Training School, appealed for her release. The Governor granted the request on February 1st when Sanger promised that her sister would never break the Comstock law again. Byrne was taken to her sister’s house for care, but this episode damaged their relationship. Byrne did not actively participate in the birth control movement after this.

Ethel Byrne’s later years were quiet. She moved to Massachusetts and returned to nursing. She died in 1955. In 1962, Alan F. Guttmacher, MD left his post as Chairman of OB-GYN at The Mount Sinai Medical Center to become the President of Planned Parenthood. The Mount Sinai connection continued.

Oct 7, 2016

(Click to expand the image)

Sixty years ago this month, The Mount Sinai Hospital said goodbye to the last of a group of 25 women from Hiroshima, Japan who had spent over a year at the Hospital having surgeries to repair injuries they suffered in the nuclear blasts that ended World War II. The group of young women were called the Hiroshima

Maidens, and the project that brought them from Japan to the U.S. was the brainchild of Norman Cousins, the Editor of the Saturday Review of Literature. He raised the funds needed for the project and enlisted the help of the Quaker community of the metropolitan New York region to house the Maidens when they were not in the Hospital. Three surgeons from The Mount Sinai Hospital volunteered their time (Drs. Arthur Barsky, Bernard Simon and Sidney Kahn), and the President of the Hospital, Alfred Rose, anonymously paid for the use of four hospital beds for the duration of the project.

The Hiroshima Maidens project was a milestone in postwar American-Japanese relations. Before leaving Japan, the girls were told by some that the American doctors were going to experiment on them. As it became clear that this was not the case, the donated funds were stretched to allow Japanese doctors to come to Mount Sinai and receive training in plastic and reconstructive surgery, thus helping to strengthen the field in Japan.

The Hiroshima Maidens project continued to have life. In 1995, one of the Maidens returned to Mount Sinai to meet with Dr. Simon. At that time she gave the Mount Sinai Archives a scrapbook of photocopies of images from Hiroshima after the blast. The next year there was a conference at Mount Sinai that celebrated the project from 40 years before, and highlighted Mount Sinai’s current international efforts. In spring 2005, for the 50th anniversary of the project, the last remaining Maiden and a group of Japanese press visited Mount Sinai once again. The group came to the Archives and looked at the photos from the 1950s and read again the newspaper accounts of the Maidens’ courageous journey to New York.

On this 60th anniversary, it is unknown if any Maidens are still alive. Still, it is comforting to know that the memory – and documentation – of the project lives on, and will not be forgotten.

Sep 28, 2016

The creation of the Mount Sinai Health System in 2013, formed by the merger of the Mount Sinai Medical Center with Continuum Health Partners, brought some of New York City’s major hospitals together under a single organizational umbrella. The individual hospitals making up the Health System, however, often themselves incorporate multiple hospitals with which they have merged and affiliated over the years. As the Archives continues to collect, process and make available the records of the former Beth Israel Medical Center, we have acquired material relating to various smaller hospitals associated with Beth Israel. The records of these institutions provide a glimpse into the wide variety of small hospitals that existed in New York during the twentieth century.

Doctors Hospital

Doctors Hospital was an exclusive voluntary hospital, founded in 1929 by members of New York City’s social elite, which catered to the needs of wealthy private patients. Its Upper East Side location on East End Avenue overlooked Carl Schurz Park and Gracie Mansion (pictured, at center). In 1987 it became part of the Beth Israel Medical Center and was briefly known as Beth Israel Hospital North before being renamed Beth Israel Medical Center Singer Division. It closed in 2004, and its building was torn down the following year; the site is now occupied by luxury residences. The minutes of the Doctors Hospital Board of Directors, recently discovered in offsite storage associated with Beth Israel, are now a part of the collection of the Mount Sinai Archives.

Jewish Maternity Hospital

The Jewish Maternity Hospital was founded in 1906. Located at 270 Broadway, it provided maternity care to the Lower East Side’s growing community of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. At the urging of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies, which hoped to consolidate its medical activities during the lean years of the Great Depression, it merged in 1930 with Beth Israel, which had recently moved to a state of the art modern hospital on Stuyvesant Square. For some time the two institutions maintained separate wards within the hospital building, but by the 1940s the Maternity Hospital had been absorbed into the obstetrics department at Beth Israel. Three volumes of its patient registers, dated 1921-1933, are housed in the Mount Sinai Archives.

New York Lying-In Hospital / Manhattan General Hospital

The New York Lying-In Hospital already had a long institutional history, dating back to the yellow fever epidemic of 1798, when it moved in 1902 to a newly built home at 307 2nd Avenue on the northwest corner of Stuyvesant Square. The hospital’s time at this location was a productive one, during which members of the hospital staff pioneered the use of pharmaceutical pain management to ease the pain of childbirth. In 1932 the New York Lying-In Hospital left the site to become the OB-GYN department of the New York Hospital at its campus on the Upper East Side. The building on Stuyvesant Square became home to the proprietary Manhattan General Hospital. In 1965 the building was purchased by Beth Israel and became the Morris J. Bernstein Institute, a pioneering inpatient facility for addiction treatment. The building was sold in 1984 and is now an apartment complex, but its origin as a maternity hospital can still be seen in the elegant sculptures of infants displayed on its facade. The records of the Lying-In Hospital itself are in the Archives of the Weill Cornell Medical College, but the Mount Sinai Archives has a small assortment of records related to the Bernstein Institute during the period that it occupied the former Lying-In Hospital building.

pioneering the use of radium as a treatment for various medical conditions. His many published articles document the breath of his surgical experience and the successes he had using radium to treat patients.

pioneering the use of radium as a treatment for various medical conditions. His many published articles document the breath of his surgical experience and the successes he had using radium to treat patients.