May 24, 2016

The cemetery at Base Hospital No.3 for Americans who died at the hospital, 1918

Memorial Day is set aside to remember the servicemen and women who have died while in service to their country. Ceremonies started after the Civil War and it became a national holiday after World War II. Since injury and death are a part of war, doctors and nurses have always been witnesses to the ravages of battlefields. The image above shows the American cemetery at Base Hospital No. 3, the Mount Sinai Hospital-staffed unit that served in France.

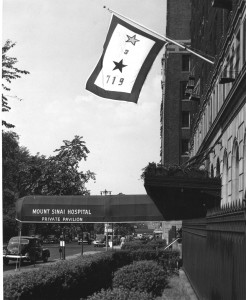

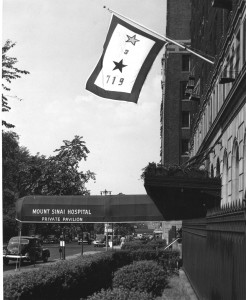

While the deaths happened abroad, the biggest impact was felt at home. It was not only families that marked their losses, but institutions as well. By World War II, service flags were a familiar patriotic symbol. The photo below shows Mount Sinai’s flag hanging from 1184 Fifth Avenue. The number on the bottom shows how many Mount Sinai doctors, nurses, staff and trustees were in the service at that time. The gold star at the top showed how many had died. By the end of the war, Mount Sinai’s numbers had grown to 802 served, nine dead.

The Mount Sinai Hospital service flag, 1944

Those nine are recognized here:

- Nils Carson

- Sydney C. Feinberg, MD

- Andrew Goldstein

- Jerome W. Greenbaum, MD

- Eugene M. Holleb, MD

- Goodell G. Klevan, MD

- Bernard Ritter, MD

- Helen Rogers, RN

- Stanley J. Snitow, MD

May 13, 2016

As the Mount Sinai Archives continues processing and cataloging the records of the Beth Israel Medical Center (today’s Mount Sinai Beth Israel), we continue to discover interesting images and ephemera from Beth Israel’s history.

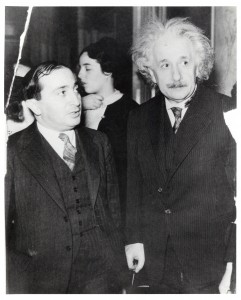

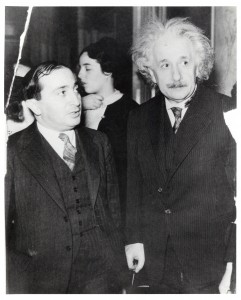

The photograph above shows Albert Einstein with Adolph Held (1885-1969), editor of the Jewish Daily Forward and brother of Dr. Isidor W. Held, a longtime member of the Beth Israel Hospital medical staff who served as President of the Medical Board from 1936 to 1938. (Update June 2017: When we first discovered this photograph in the collection, it had been incorrectly identified as a photograph of Dr. Held rather than his brother Adolph. Thanks to the family member who contacted the Archives with a correction.)

Dr. Held, a gastroenterologist, was involved in Jewish refugee aid in the aftermath of World War I, and during the rise of Nazism he became active in the movement to help medical and scientific emigres escape from Nazi Germany and its conquered territories, raising funds and publishing articles on behalf of persecuted Jewish physicians. These activities brought him into contact with Albert Einstein, who was himself a refugee from Nazi persecution and a vocal activist on behalf of other potential emigres.

This photograph is the only item in the Beth Israel collection that documents the relationship between Einstein and Dr. Held, but the Einstein Archives Online, a comprehensive directory of Einstein’s manuscripts, includes numerous entries for letters to and from Held and his wife Fanny. In 2006, a 1938 letter from Einstein to Held discussing the situation in Germany was sold at auction; the catalog listing includes a translation of the letter, which discusses their unsuccessful attempts to help an internist named Rudolph Ehrmann escape the “German gangsters.” (The following year, they were successful in obtaining passage to New York City for Dr. Ehrmann, who opened a private practice and became one of Einstein’s personal physicians.)

Dr. Held passed away in 1947. In addition to his legacy as an administrator, clinician and teacher of house staff, and the lives he saved as a refugee advocate, his posthumous impact at Beth Israel included an important annual lecture series endowed in his memory, which lasted until at least the late 1980s and brought numerous prominent physicians to BI’s downtown campus.

May 2, 2016

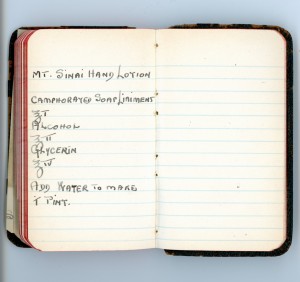

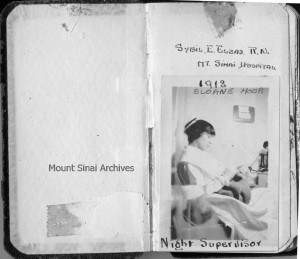

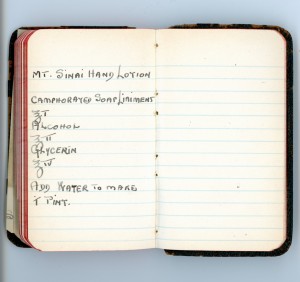

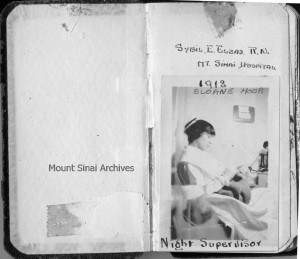

In honor of National Nurses Week, the Mount Sinai Archives would like to recognize that for over 100 years, Mount Sinai nurses have been doing it all, and then some. When she was a student at The Mount Sinai Training School for Nurses, Class of 1917, Sybil E. Elzas created a little notebook containing important things she needed to know on her clinical rotations, and then once out on her own as a graduate nurse. (Most professional nurses at this time still did private duty nursing, not hospital work.) The notebook was sized just right to slip into the pocket of her uniform’s apron. After pages and pages of definitions of terms and lists of operating room tray set-ups and dressings, towards the back of the book is a lone page noting the recipe for “Mount Sinai Hand Lotion.” Why purchase something nurses could so easily make, and at reduced cost?!

Nurses, still making a difference at Mount Sinai, 100 years later.

Inside cover of the clinic notebook belonging to Sybil E. Elzas. She is shown here as a student while on rotation to Sloane Hospital. The recipe for the lotion is at the end of the volume.