Jul 31, 2018

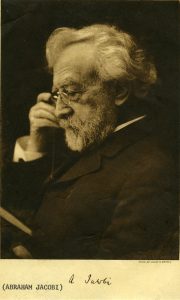

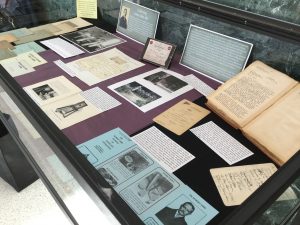

The Aufses Archives recently announced the opening of a new digital collection of letters to and from Abraham Jacobi, MD, the “father of American pediatrics” and a towering figure in the history both of Mount Sinai and of nineteenth-century American medicine. The letters, most of which deal with the staffing and administration of Mount Sinai’s outpatient clinics, contain the historical traces of many other physicians and surgeons who passed through Mount Sinai in the late nineteenth century. Some went on to quiet careers in private practice; others were famous in their time but have since been forgotten.

One letter in the collection, dated March 1st, 1879, contains an update from Rudolf Tauszky, MD, Secretary of the Medical Staff of the Out-Door Department (that is, the outpatient clinics), informing Dr. Jacobi of changing staff assignments. Among other changes to the roster, Doctors M.J. and E.J. Messemer had been appointed to the internal medicine clinic.

These forgotten names piqued our curiosity. Who were they? How were they related? Research confirmed that the Messemers were brothers and had graduated from Bellevue Hospital Medical College (predecessor of today’s NYU School of Medicine) a few years previously. At a time when the modern system of clinical instruction was still in its infancy, positions in the charity outpatient clinics of a prestigious hospital were a valuable way for recent graduates to gain practical experience on the way to establishing a private practice.

Further research revealed the subsequent career of Michael Jean Baptiste (M.J.B.) Messemer, MD. He turned out to have been a colorful figure who was a minor celebrity in old New York.

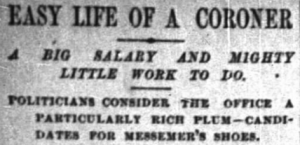

New York Times, July 21, 1890

New York Times, July 21, 1890

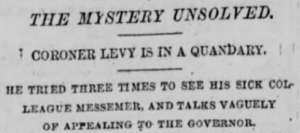

New York Tribune, May 27, 1891

New York Tribune, May 27, 1891

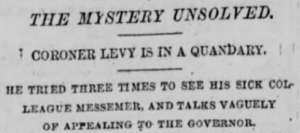

New York City in the late nineteenth century was limited to Manhattan and a portion of what is now the South Bronx, and city politics were firmly under the control of Tammany Hall, of which Dr. Messemer was a loyal member. Today, the Chief Medical Examiner of New York City is a highly regarded professional, but in the 1880s the position of City Coroner was considered a “plum” job for Tammany loyalists whose incumbents could draw a high salary with relatively little work. Dr. Messemer became one of the city’s four coroners in 1883. One colleague, Coroner Levy, charged Messemer with spending much of his time in recreational travel, pleading sickness rather than attending to his public duties. Levy remarked sarcastically to a New York Tribune reporter that “I am afraid that the public is skeptical about him.”

New York Times, December 10, 1885

New York Times, December 10, 1885

Dr. Messemer did investigate cases, however. Many of these were widely reported in the popular press, leading to accusations that Dr. Messemer was publicity-hungry and using the office of coroner to promote himself. In 1885, on the death of railroad magnate William Henry Vanderbilt, Messemer rushed to Vanderbilt’s mansion in the company of a reporter to inspect the body for foul play. A colleague accused him of “looking for notoriety,” adding that such an uninvited inspection was “wrong and uncalled for” under the Police Department rules governing suspicious deaths.

New York World, March 3, 1894

New York World, March 3, 1894

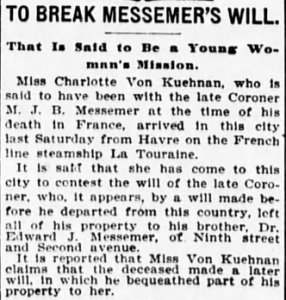

Dr. Messemer passed away in 1894 while traveling in Europe. The “widely known New Yorker,” wrote the obituary columnist of the New York World, “was ever willing to help his friends among newspaper men get news, and thereby get notoriety for himself. To-day Messemer furnishes another and a last story.” The will that Dr. Messemer had placed on file in New York left his entire estate to his brother, but his European mistress claimed he had written her into his will on his deathbed. Although she traveled to New York to contest the will in person, the suit was eventually settled in favor of his brother.

New York Evening World, April 23, 1894

New York Evening World, April 23, 1894

Jul 13, 2018

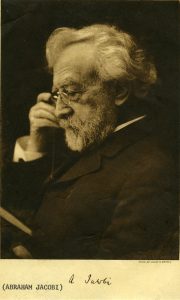

The Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives at Mount Sinai is proud to make available two groups of digitized correspondence to and from Abraham Jacobi, MD (1830-1919), the “father of American pediatrics.” Dr. Jacobi was a towering figure both at Mount Sinai, where he chaired the Medical Board for twenty-five years and is the namesake of the Alumni Association’s Jacobi Medallion, and in the broader world of the history of medicine. He was the first Professor of Pediatrics at an American medical school (beginning at New York Medical College and later moving to Columbia), and under his leadership Mount Sinai created the first department of pediatrics at a general hospital in New York City.

This digitized collection is the work of two institutions, the Aufses Archives and the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, which generously made available scanned images of their own collection of Jacobi correspondence. By bringing together two geographically separated collections whose contents overlap in time and subject matter, this digitization project, which includes full transcriptions of all manuscripts, makes Dr. Jacobi’s story more accessible to scholars and the general public. The Mount Sinai letters are available here, and the Historical Medical Library’s letters are available here.

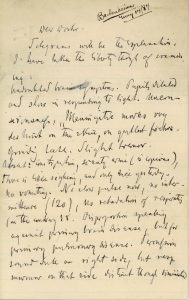

Although the majority of the collection deals with the staffing and administration of The Mount Sinai Hospital and its Out-Door Department (the outpatient clinics), one letter in the collection provides a fascinating glimpse into Dr. Jacobi’s medical practice. In 1884, at the request of an unidentified colleague, he examined an unnamed patient and replied with a brief but dense handwritten note describing his findings. Like modern physicians, Dr. Jacobi used close attention to his patient’s symptoms to perform a differential diagnosis. With no laboratories or high-tech equipment at his disposal, he relied solely on the evidence of his immediate senses, counting the pulse and percussing the chest to make a tentative diagnosis of secondary meningitis brought on by a pulmonary condition.

Dr. Jacobi comments that the “prognosis [is] bad, it is true — but still, who can tell?” His uncertainty tempered with hope reminds us that in hindsight, the decade of the 1880s was a pivotal time for modern medicine, when therapeutics had not yet caught up with rapid advances in accurate diagnosis. Nothing more is known of this patient or his eventual fate.

Jun 29, 2018

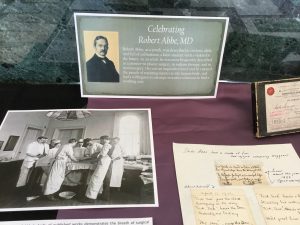

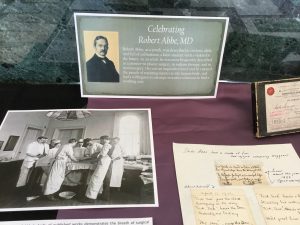

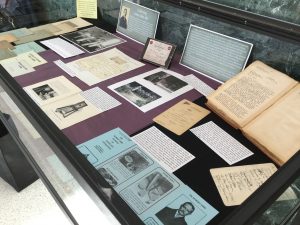

A new exhibit is now on display in the Mount Sinai West hospital lobby. Celebrating Robert Abbe, MD aims to share the many sides of Dr. Robert Abbe: the medical pioneer, the innovator, the artist, and the collector.

A new exhibit is now on display in the Mount Sinai West hospital lobby. Celebrating Robert Abbe, MD aims to share the many sides of Dr. Robert Abbe: the medical pioneer, the innovator, the artist, and the collector.

A native son of New York, Robert Abbe was born on April 13, 1851 and raised on Dutch Street in lower Manhattan. He attended public schools and took evening classes at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art to develop his talents for drawing and painting. He earned an undergraduate degree from the College of the City of New York in 1870 and joined the faculty there after graduation, teaching Drawing, Geometry, and English. He completed an MD degree in 1874 from the College of Physicians and Surgeons, and spent his residency at St. Luke’s Hospital. He later became an Attending Surgeon there, as well as Roosevelt Hospital (now Mount Sinai West), the Cancer Hospital, New York Babies Hospital, Ruptured and Crippled (today’s Hospital for Special Surgery), and Woman’s Hospital.

As a youth, Robert Abbe was described as curious, alert, and full of enthusiasm, a keen student with a vision for the future. As an adult, he was most frequently described as a pioneer – in plastic surgery, in radium therapy, and in neurosurgery. His was an inquisitive mind and he enjoyed the puzzle of repairing injuries to the human body, and had a willingness to attempt inventive solutions to find a working cure.

On view in the exhibit is a small sampling of published articles by Abbe documenting the broad variety of surgeries he performed, including neurosurgery, treatments for various problems of the hand, gallbladder, and cancer of the cheek, jaw, and breast. Later in his career, he wrote on the use of radium in the treatment of various conditions.

Abbe continued to exercise his artistic talents into adulthood, not only as a fine plastic surgeon, but also as a painter. Ever curious to try new things, when the Lumiere brothers of France developed a new method for taking color photos using a glass plate and various salts in 1905, Abbe was quite interested. By 1907 it was available in the US, and Abbe was among the first to experiment with the method by photographing family and friends, producing some lovely images that have a delicate and painting-like appearance. Two of these images are on display in the lobby case.

Another of Abbe’s amusements was collecting documents and photographs of or about famous medical persons. He created scrapbooks on such notables as Louis Pasteur, Benjamin Rush, Edward Jenner, Joseph Lister, and Marie Curie. He also acquired several objects of these notables. Between 1911 and 1923 he donated this collection to the College of Physicians in Philadelphia. On display in the exhibit is a photograph of Marie Curie in her laboratory, and another of the quartz-piezo-electro meter, which she used to determine the strength of electron discharge from radium. In 1921, at Abbe’s prompting, she donated it to the “Abbe Cabinet,” as his collection is called, at the College of Physicians, where it remains on display.

The high esteem in which Abbe was held is documented by his 70th birthday celebrations, which were held at the New York Yacht Club and attended by many friends and relations coming together for a dinner in his honor. On display are two dinner menus for the evening, one of which was autographed on the back by several well-known physicians in attendance. Along with the menu is a bound volume of typed copies of letters he received on the happy occasion conveying best wishes and fond remembrances from colleagues, friends, staff, and former students from around the country. The book is opened to a letter from William J. Mayo, MD of the Mayo Clinic, who was among his students.

During his later years Abbe spent summers in Bar Harbor, Maine where he developed an interest in the Native American population of the area. He began collecting Native American tools and Stone Age artifacts he found. He dreamt of creating a museum to display his extensive collection, raised funds to do so and designed many of the exhibits himself. The museum opened only five months after his passing in 1928. A pamphlet from the museum is included in the exhibit.

Please stop into the lobby at Mount Sinai West and browse the display, which is on view through October.

Please stop into the lobby at Mount Sinai West and browse the display, which is on view through October.

Jun 21, 2018

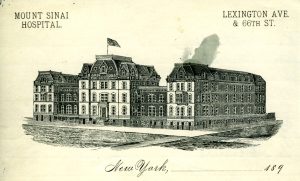

The second site of the Hospital on Lexington Avenue

This is an excerpt from the minutes of the Board of Directors of The Mount Sinai Hospital, March 11, 1888. It is a report from Mr. De Witt J. Seligman, a Director, concerning the proper verification of deaths occurring in the Hospital. The punctuation has not been changed. It provides an interesting view into what was then – and now – a very important issue: how to determine when someone is, in fact, dead.

“Mr. Seligman who was appointed a committee of one…read the following report:

To the Board of Directors of Mount Sinai Hospital:

Having been appointed at the last regular meeting of your Board a Committee of one to look into the matter of certifying to deaths I beg to submit the following report.

In getting at the facts of this matter I have seen three doctors of our visiting staff, the Pathologist of the New York Hospital, the House Surgeon and the House Physician of Mount Sinai Hospital and the Superintendent of Mount Sinai Hospital. There can be no doubt that it happens at times that patients are declared dead before life has become extinct. The Superintendent of our Hospital informs me that on one occasion a nurse told him that her patient was dead and that she was going to announce it to the doctor. The superintendent, Mr. Hadel, went to the Ward and found the alleged dead man sitting bolt upright.

A man informed our Superintendent, Mr. Hadel, that when he was a patient at Blackwell’s Island he was being carried from the Ward to the dead house. On the way they passed through the open air and the effect was that the man on the stretcher became revived and lived to tell this tale of carelessness to our Superintendent. Only this winter a relative by marriage of my wife was, I am informed, declared dead by a physician, but today that same man is as lively as a cricket. Had he been a patient of the Mount Sinai Hospital might he not under our present rules, have ·been hurried from his warm bed in the Ward into the death house and there frozen to death in a short time?

The Pathologist of the New York Hospital informs me that the Ambulance surgeon of the New York Hospital has been repeatedly in doubt as to whether a patient was dead or not and the same Pathologist of the New York Hospital tells me that a certain Dr. Ridlow thought a patient was dead and but two hours later the patient showed life; on the following day Dr. Ridlow again thought that the same patient was dead but even after that on the second day the patient showed life. There was in this case trouble with the heart. An intelligent gentleman connected with the Mount Sinai Hospital as a Director informs me that he and his wife have a mutual agreement by which in the case of the supposed death of one of them, the survivor is to carry out the following agreement: the word of the family physician is not to be taken that death has come but an outside physician is to be summoned to apply the death tests. After that is done no ice is to be placed on the body for 8 hours and the burial is not to take place for three days. In a large institution like ours where deaths are naturally occurring continually, the question arises, what method shall we adopt to avoid the possible mistake of hurrying a supposed corpse into the dead house where in case some life is still in the body it would soon by the sudden change of temperature be frozen out of the body.

One of our visiting physicians whom I saw suggested that the supposed corpse be placed in a warm room for 6 hours and that after 6 hours a second examination be made and then if no sign of life be found place the corps in the dead house. If decomposition has already set in this 6 hours additional precaution, the said visiting physician thought, ought not be taken, nor ought it be taken in warm weather when the cool temperature of the dead house would even aid to revive the flickering flame of life.

This idea seems to me the best idea that was suggested provided it be conscientiously carried out at the Hospital. But whatever rule you may make, one thing is sure and that is that no one but the House Physician on his side and no one but the House Surgeon on his side ought to make the death tests and in each and every case the House Physician or the House Surgeon ought to feel and bear the whole responsibility. To this end I would recommend that we have printed slips which shall run about as follows:

Mount Sinai Hospital, N. Y.

This is to certify that I have this day carefully examined __________________________

a patient of Mount Sinai Hospital in Ward No.____ Bed No.____ and found (him or her) dead.

These slips are to be signed only by the House Surgeon on his side of the Hospital and all these slips are to be kept by the Superintendent of Mount Sinai Hospital in a book for that purpose. In consultations with Drs. Rich and Walsh, the House Surgeon and House Physician of this Hospital, I find that there are no rules as to who shall declare that life has left a patient. Dr. Rich informed me that he always attended to this but Dr. Walsh informed me that in nearly all cases he did and in the remaining cases he left the investigation of the alleged corpse to any doctor, it mattered not which one.

The Pathologist of the New York Hospital informs me that at the New York Hospital the House Physician or the House Surgeon and nobody else testifies to death and even if he has been but a short time previous to death say three times at the bedside said House Physician or House Surgeon is personally compelled to go to the Ward and examine the patient after he has been declared dead. Even at night at the New York Hospital the House Physician or the House Surgeon is compelled to go to the body and examine it.

It may be of interest to you to know that at the New York Hospital every single corpse is washed and put in a shroud and as this operation usually takes half an hour or more, in the opinion of the Pathologist of the New York Hospital who gave me this information, is an additional safeguard against treating the patient as dead before life has left the body.

A great deal more could be written on this important subject, but I think I have written enough to make it clear that this Hospital should have the most stringent rules that can possibly be made in the matter of death certification.

Respectfully submitted

(signed) DeWitt J. Seligman

Mr. [Isaac] Wallach moved that the report of Mr. Seligman dated March 11, 1888 be spread on the minutes in full and that the recommendations contained in said report that the House Physician and House Surgeon must examine persons supposed to have died and sign certificates of death and no one else, in the manner suggested in said report.

That a book be provided for the purpose by the Comm. on Printing.

That the suggestion to place alleged dead persons for 6 hours in a warm room from and during cold months before such bodies are placed in the dead house be referred to the Executive Committee to provide the room if possible.

These provisions are intended as safeguards to prevent the slightest possibility of patients being placed in Dead House who may be apparently dead but not actually so. This whole motion of Mr. Wallach was adopted.

May 25, 2018

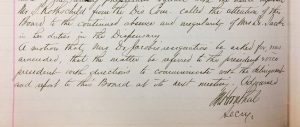

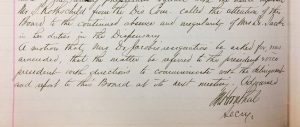

In 1875, The Mount Sinai Hospital selected Mary Putnam Jacobi, MD (1842-1906) to be the Chief of the newly established Children’s Clinic. Abraham Jacobi, MD, her husband, was an important member of the Mount Sinai medical staff and is today considered the Father of Pediatrics in this country. Still, the Trustees did not want him to be in charge of both the inpatient and outpatient services, so Mary Jacobi was appointed. All was well for some years, but in May 1884, the Board of Trustees’ minutes record the “continued absence and irregularity of Mrs. Dr. Jacobi in her duties in the Dispensary.” There was a motion seeking her resignation, but this was amended to instead send the president and vice-president of the Board to speak with “the delinquent” and report back. The subsequent meeting does not have a report on the visit with “Mrs. Dr. Jacobi,” but it is known that she resigned from the staff in October of 1886, more than two years later. Did being “Mrs.” Jacobi save her appointment? Perhaps. The very few other female doctors on staff were known as just Dr. The fact that Mary Putnam was married to Abraham Jacobi probably loomed large in the eyes of the Mount Sinai trustees. He remained associated with the hospital until his death in 1919.

The minutes of the Board of Trustees of The Mount Sinai Hospital, May 1884

New York Tribune, May 27, 1891

New York Tribune, May 27, 1891 New York Times, December 10, 1885

New York Times, December 10, 1885