Aug 27, 2020

This is a guest blog post by summer intern, Lily Stowe-Alekman. Lily is a junior at Smith College where she studies History, Archives, and the Study of Women and Gender.

Even before given access to traditional pathways of change, women at The Mount Sinai Hospital have worked to make change in the institution. From the opening of The Mount Sinai Hospital in 1855, the wives and daughters of the Board of Trustees worked to provide services in order to provide comfort to patients and to address their social and emotional well-being. By 1917, the first year that women were allowed on the Board, the role of women, and their expectations of that role, had substantially changed. The growing power of women was expressed by the creation of their own organization to exert influence over the life of the Hospital, the Social Service Auxiliary. And according to Helen Rehr, DSW, the second Edith J. Baerwald Professor of Community Medicine (Social Work), they were a force to be reckoned with.1 When prompted in an interview about the Auxiliary, “…they weren’t social butterflies having their tea. That’s not an image you would draw,” Rehr responded “Not these women, never. In the 28 years that I’ve known them I don’t recall having tea with them. No, they were women who came with a commitment to the social organization.” Hortense Hirsch, who served on the Auxiliary Board and Board of Trustees as one of the first woman able to be a Trustee, is a powerful example of the trailblazing women of the Auxiliary Board.

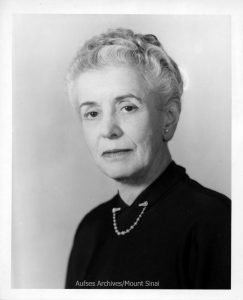

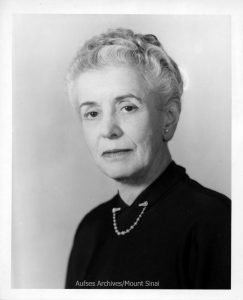

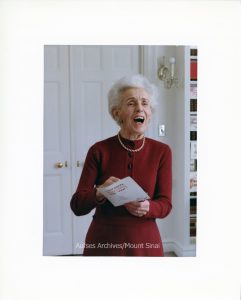

A portrait of Hortense Hirsch, circa 1960.

In 1923, Mrs. Hortense Hirsch (1887-1990) began her work with the Social Services Auxiliary (today’s Auxiliary Board), of which she would continue to be a member for sixty-five years, including a tenure as president from 1951-1956. From there, she was elected to the Board of Trustees in 1932, where she remained until becoming an honorary trustee in 1986. She sat on several committees of the Board, including as a member of the Committee on Building Maintenance and Equipment, Vice-Chairman of the Committee on Social Service, Chairman of the Committee on Convalescent Care, and as a member of the Committee on Ladies’ Auxiliary. Hirsch was president of the Neustadter Home for Convalescents beginning in 1937 when the Home affiliated with Mount Sinai, until she stepped down from the post in 1953.

A photograph of (from left to right) Helen Benjamin, member of the Women’s Auxiliary Board; Mrs. Edith Lehman, the first President of the Auxiliary Board from 1916-1917, Mrs. Ruth Cook, President from 1917-51; and Mrs. Hortense Hirsch, the presiding President of the Board at the fiftieth anniversary of the Auxiliary Board in 1956. Helen Benjamin holds a picture of the first social work volunteer from 1907.

Hortense Hirsch lived to be 103 years old, and by all accounts she remained steadfast in her dedication to social work and volunteerism for her whole life. After she graduated from Smith College in 1907 at the age of 19, she married Walter Hirsch and then moved to New York City in 1909. She began her work as a volunteer at Mount Sinai in 1917. The Federation of Jewish Philanthropies later referred to her as the “honorary ‘Dean of Social Work Volunteers.’” As a thoroughly involved volunteer and then Auxiliary Board member, Hirsch dedicated many hours to the hospital. Dr. Helen Rehr remarked in 1982, “The demands on her were great, but she always rose to it. There was no question on that score.”

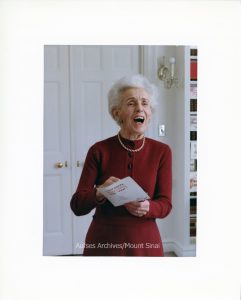

Portrait of Hortense Hirsch, circa 1976.

Hortense Hirsch’s personality leaps off the pages of archival materials. When at Smith College, she maintained her own horse and buggy, which was against the rules, by paying a farmer for boarding, effectively evading the administration. In a New York Times article documenting her 100th birthday celebration, her daughter Carol Kridel told them, that while Hirsch was too ill to attend and she had to stay in bed, she was still “wearing a pink bedjacket and a pink bow in her silver hair.” The article also includes a story of Hirsch “[coming] to her 85th birthday and [tossing] her skirts high to show she approved of the latest rage—hotpants.”

Hortense Hirsch’s work on the Social Service and Women’s Auxiliary Board helped to transform the hospital. She worked tirelessly as a volunteer and board member. Hirsch’s work and legacy came from and continued those of the women who originally found pathways to affect changes at The Mount Sinai Hospital in the late 1800s. Hirsch served on the Board of Trustees, an opportunity that was not available to the women of previous generations. As Dr. Helen Rehr stated, “the Mrs. Hirsches are an outgrowth of that group of women who were the wives of the board of trustees” and ultimately transformed the hospital in the process.

Aug 21, 2020

This is a guest blog post by summer intern, Lily Stowe-Alekman. Lily is a junior at Smith College where she studies History, Archives, and the Study of Women and Gender.

As a summer intern with the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives, I have become acquainted with Mount Sinai’s history and the efforts that go into preserving its legacy. One of the projects I have worked on is cataloging The Mount Sinai Hospital News, an in-house tabloid-style newsletter for Mount Sinai employees. Colleen Stapleton, Patient Navigator for the Liver Education & Action Program at Mount Sinai, volunteered with the Archives this spring and digitized the newsletters from 1958-71. In my work cataloging, I read some really entertaining stories that offered a glimpse into the personal lives of people who worked in The Mount Sinai Hospital (later Medical Center), whether that be birth announcements of their children, quirky stories about the things employees did outside of the hospital, or articles about celebratory dinners and ceremonies. One can also not forget the hospital’s bowling team.

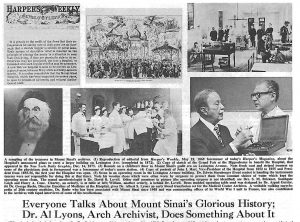

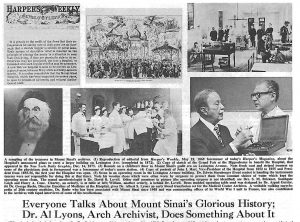

While cataloging in July, I came across a story that made me pause because it felt like a full circle moment. The October 1971 issue of The Mount Sinai Medical Center News featured an article called “Everyone Talks about Mount Sinai’s Glorious History; Dr. Al Lyons, Arch Archivist, Does Something About It.” This article has history of the Aufses Archives and is within the archive. While the Aufses Archives is a site of historical preservation, it has its own history as well.

Caption: The objects featured in the article header are still in the Arthur H. Aufses Jr. MD Archives today!

The creation of what is now the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives is due to the work and advocacy of Dr. Albert S. Lyons in the 1960s to 1980s. Over this time, Dr. Lyons advocated for the need of creating the archive and in 1986, secured its future with the hiring of a full-time archivist, Barbara Niss, who remains the Director today. Dr. Lyons (1912-2006) spent over sixty years of his life working at Mount Sinai. He began as a surgical resident at Mount Sinai Hospital in 1938. He went on to become the founder and Chief of the Intestinal Rehabilitation Clinic and worked to help support patient needs post-surgery. He was also a Clinical Professor of Surgery at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. He wrote a well-known book, Medicine: An Illustrated History, a volume of over six hundred pages, charting medicine from the prehistoric era to the twentieth century.

Beyond his clinical work, Dr. Lyons was committed to Mount Sinai’s institutional history and to history of medicine in general. He taught the History of Medicine elective courses in the medical school. In the 1960s, he convinced the hospital board to collect the institutional history of the hospital. In 1966, he was made Hospital Archivist by Mr. Gustave L. Levy, the Chairman of the Board of Trustees. Dr. Lyons’ passion for preserving the history of The Mount Sinai Hospital overlapped with the discussions and planning of Mount Sinai School of Medicine, which welcomed its first students in the fall of 1968. In 1970, he was given the official title of Medical Center Archivist. Dr. Lyons also contributed a broad range of valuable materials to the Archives, including over eighty-five oral history interviews dating to 1965, a formative time for the field of oral history as well as for the Medical Center, as the School planned for and welcomed its first students.

In October of 1971, The Mount Sinai Medical Center News wrote about Dr. Lyons’ archival work. The article highlights the work and efforts of Dr. Lyons and serves as a call to action of sorts for the archive. Dr. Lyons is quoted in the first line as saying, “When in doubt, don’t throw it out.” He goes on to say that “too much of Mount Sinai’s past has already gone up in smoke,” due to people throwing out items without realizing their significance. He stresses as well that ordinary everyday materials are archival. He stresses that history is not necessarily in the distant past, that the events of the previous day are history. In this sense, Dr. Lyons de-mystifies the archives by showing that it should be in connection with the present moment and is not a disconnected abstract institution. The closing paragraph of the article instructs readers, “If you’ve uncovered some papers or objects you think may be worth saving, are planning some event to make current Medical History, etc. Drop Dr. Lyons a note.” In turn, “He and the Future will thank you!”

SOURCES

Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives and Records Management. “Lyons, Albert S., MD, Papers, 1932-2000.” Collection Guides. https://icahn.mssm.edu/about/ait/archives/collection/albert-lyons.

Aufses, Arthur H., Jr., and Barbara Niss. This House of Noble Deeds: The Mount Sinai Hospital, 1852-2002, New York University Press, 2002. ProQuest Ebook Central, xi.

“Everyone Talks About Mount Sinai’s Glorious History; Dr. Al Lyons, Arch Archivist, Does Something About It.” Mount Sinai Medical Center News. October 1971. 5, 10.

Aug 12, 2020

George Nicholas Papanicolaou was born in the seaport town of Kymi, on the Greek island of Euboea, on May 13, 1883. He entered medical school to please his father, Nicholas, who was a physician, and the mayor of their town. He graduated medical school in 1904. In 1906, after completing military service obligations, he joined the family practice, but was more inclined to scientific research.

George Nicholas Papanicolaou was born in the seaport town of Kymi, on the Greek island of Euboea, on May 13, 1883. He entered medical school to please his father, Nicholas, who was a physician, and the mayor of their town. He graduated medical school in 1904. In 1906, after completing military service obligations, he joined the family practice, but was more inclined to scientific research.

[photo: George Nicholas Papanicolaou (1883–1962) (obtained by public domain at http://www.hmsny.org/en/archivesgallery/news-bulletins/hms-ny-news-April-2012.html). ]

In 1907, he moved to Germany to study zoology, earning a PhD in 1910. Afterwards, Papanicolaou worked as a physiologist. In 1913, he and his wife immigrated to New York. He worked in various odd jobs for a time until he was able to find part-time employment in the Department of Pathology and Bacteriology of the New York Hospital. A year later he moved to the Department of Anatomy at Cornell Medical School and worked as an assistant; his wife was hired there as his technician.

His assignments included studying sex determination in guinea pigs. Part of this testing required harvesting the animals’ eggs just before ovulation, a guessing game that usually meant killing many of them before finding an animal at the right stage to be useful to the study. Instead, Papanicolaou developed a method to chart a guinea pig’s menstrual cycle by using a nasal speculum to take vaginal swabs and preparing a smear slide, which, under a microscope displayed distinctive cytologic patterns that helped him predict ovarian status. Eventually he broaden this method to human subjects to study similar smears in women. (Some have speculated that his wife was his first subject in this study.) He was surprised to find malignant cells present in some of these smears, which led to further study. In 1928, he presented a paper on the smear procedure as a method to detect cervical cancer in women. Unfortunately, this report was not well received by the general field.

He began on a clinical study collaboration with Herbert F. Traut, MD, a gynecologic pathologist at Cornell, in 1939. During this study, Papanicolaou detected many asymptomatic cancer cases, some in such an early stage that they were undetectable on biopsy. Traut and Papanicolaou published a paper titled, “Diagnosis of uterine cancer by the vaginal smear,” in 1943, which was a step forward in accepting the ‘Pap smear’ a standard procedure for detecting and preventing cervical cancers.

Why am I telling you this? Dr. Papanicolaou served as consulting OB-GYN staff for St. Luke’s – Woman’s Hospital Division from the 1956 to the early 1960s.

George Nicholas Papanicolaou was born in the seaport town of Kymi, on the Greek island of Euboea, on May 13, 1883. He entered medical school to please his father, Nicholas, who was a physician, and the mayor of their town. He graduated medical school in 1904. In 1906, after completing military service obligations, he joined the family practice, but was more inclined to scientific research.

George Nicholas Papanicolaou was born in the seaport town of Kymi, on the Greek island of Euboea, on May 13, 1883. He entered medical school to please his father, Nicholas, who was a physician, and the mayor of their town. He graduated medical school in 1904. In 1906, after completing military service obligations, he joined the family practice, but was more inclined to scientific research.