Roosevelt Hospital Ambulance Service – 1877 to 1972

The Emergency Medical Service (EMS) has its roots in battlefield medical care, dating back as far as ancient Greece. American emergency medical services began to take the form we recognize today during the Civil War, when plans for medical care of battlefield injuries was organized in an intentional fashion under General George B. McClellan.

The first American civilian ambulance corps formed in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1865. New York City soon followed with its first ambulance service at Bellevue and Allied Hospital, a public hospital, in 1869, under the direction of the newly appointed NYC Sanitary Superintendent, Edward Dalton, MD, a former Union Army surgeon. Private hospitals soon followed suit.

It was common when Roosevelt Hospital opened in 1871 for patients to arrive by themselves, if mobile, or to come in aided by family or friends. However, Hospital Superintendent Horatio Paine, MD, was worried and informed the Board of Trustees that

…persons injured accidentally or overcome by heat in the immediate neighborhood of the Hospital are carried by the police almost invariably, first to the police station in 47th street, and thence by ambulance, … to the Reception Hospital in 99th street … a distance of over 2 and a half miles. Persons injured or sun-struck on the very block on which this Hospital stands, have thus been carried past its doors.

Dr. Paine feared that Roosevelt Hospital would incorrectly appear as unwilling to receive or care for emergency cases at any hour. He collaborated with other hospitals and City authorities to establish ‘casualty districts’ in the City, and in September of 1877, Roosevelt Hospital established an ambulance service for emergency care and, along with St. Luke’s, New York, and Bellevue Hospitals, provided coverage over one of the casualty districts mapped out by the City.

Horse-drawn carts were the norm from the start of Roosevelt’s service until 1900. Equipment for each of the two ambulance carts may have included tourniquets, sponges, bandages, splints, blankets, and if called for, a straitjacket. This kit was stored under the driver’s seat, along with a quart of whiskey or brandy, which was used as pain relief at that time. At first, the ambulance deployed with only a driver, but it soon became clear that an on-board physician to assess a patient’s condition and perhaps administer treatment while on route to the hospital was necessary. House staff were the first assigned to this service, in rotation. Later on a team of ‘ambulance surgeons’ was formed as a regular unit under the surgical service.

Horse-drawn carts were the norm from the start of Roosevelt’s service until 1900. Equipment for each of the two ambulance carts may have included tourniquets, sponges, bandages, splints, blankets, and if called for, a straitjacket. This kit was stored under the driver’s seat, along with a quart of whiskey or brandy, which was used as pain relief at that time. At first, the ambulance deployed with only a driver, but it soon became clear that an on-board physician to assess a patient’s condition and perhaps administer treatment while on route to the hospital was necessary. House staff were the first assigned to this service, in rotation. Later on a team of ‘ambulance surgeons’ was formed as a regular unit under the surgical service.

Ambulance service gained acceptance over time, as hospitals began to be seen as a safe place to go, a place for healing. For the year 1883, the hospital answered over 734 calls and spent $1,714.11 on feed, straw, repairs, harnesses, horseshoeing, telegraph service, purchase of horses, and also for legal expenses for accidents. That year the service also spent $1,310.92 on whiskey, wine, ale, porter, beer, and mineral waters! By its tenth year of service, ambulance calls rose to 1,122. By its twentieth year of service in 1897, total calls more than doubled the number at 3,300.

The Hospital annual report for 1899 notes that a new accident building opened with a ground floor emergency room and an ambulance court, placing more emphasis on emergency services overall. Accordingly, the service expanded to three ambulances and drivers, answering 4,041 calls.

By 1900 the horse-drawn ambulance was replaced by electric cars, which weigh 4,800 pounds and traveled at up to sixteen miles an hour. Costing $3,000.00 each, the Hospital received two as gifts – one of which was from a prominent physician of the city. The vehicles were seven feet, six inches long on the inside, eighteen inches longer than most ambulances, and had room for three reclining patients, or eight patients if they sat up. The cars were battery powered. The batteries were in a box suspended from the body of the vehicle, to be recharged each time the car returned to the Hospital. In an emergency, an extra set of batteries came with the car and could be put into place in two minutes. The batteries ran 25 miles on one charge.

Service costs ran between $3,000 and $4,000 for each vehicle in 1901 and 1902, in addition to the cost of re-fitting the necessary mechanical arrangements to store them in the old horse stables on the hospital grounds. Costs to run the service rose to $6,000 in 1903, when Hospital administrators decided to discontinue the electric cars, and return to the cheaper and more dependable horse-drawn carts.

On March 1, 1909 the ambulance service was completely discontinued, again, citing the high operational costs, partly due to the legal costs of frequent accidents. New York, Flower, and J. Hood Wright Hospitals stepped in to cover the area left without service.

That same year the State Charities Aid Association published a bill to create a Board of Ambulances – a central control agency over ambulance service in the City. Called The Newcomb-Hoey Bill, it suggested that such a Board consist of the Commissioner of Police, the Commissioner of Public Charities, and the President of the Trustees of Bellevue and Allied Hospitals. Such a Board would cover service over Manhattan and the Bronx. A sister agency, run by the Commissioner of Public Charities, would have control over Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island.

Each Board would have general control over and establish the rules and regulations governing all ambulance service in their districts, except those maintained by the Board of Health. It would establish casualty districts, and be the central clearinghouse to receive and distribute ambulance calls to the various hospital units.

The late 1930s was a time of self-assessment and re-evaluation for Roosevelt Hospital. The Hospital was nearly 70 years old and the facilities needed renovation, updating, and expansion to meet the growth of the neighborhood it served. Part of this renewal was the reintroduction of the ambulance service.

On July 5, 1939, at noon, Roosevelt Hospital resumed its ambulance service with modern motor vehicles. Two new ambulances, painted dark gray and white, cost $3,000 each. The Department of Hospitals and the Hospital shared the cost of the service’s operation. Ambulance drivers received extensive training in first aid, especially in dealing with fractures, because World War I had depleted the medical staff and a physician couldn’t be spared. The 1939 Hospital annual report lists five doctors appointed as ambulance surgeons, but they did not ride with the car unless requested by the police officer calling for it.

Prior to its discontinuation in 1909, Roosevelt Hospital’s ambulance answered calls from West 27th Street to West 86st Street and from the Hudson River to Sixth Avenue, including Central Park below 86th Street. When the service resumed in July of 1939, its area covered West 39th to West 72nd Streets between Fifth Avenue and the Hudson, including all of Central Park south of 86th Street.

In the mid-1940s the eastern border of its service was moved to the west side of Park Avenue, except for the area around Grand Central Station, which was served by Grand Central Hospital, and then again to the west side of Lexington Avenue. At this point, Roosevelt Hospital covered the largest casualty district in the City.

Emergency Department renovations in 1961, along with the closing of Grand Central Hospital that same year, forced the expansion of the ambulance district by 130 additional city blocks. The Hospital now covered midtown Manhattan from the Hudson to the East River between East 42nd Street and East 79th Street. Lenox Hill Hospital resumed its ambulance service in 1965, allowing Roosevelt Hospital to reduce its northern border from East 79th Street to East 59th Street and its eastern border returned to the west side of Fifth Avenue.

By 1946 World War II was over and New York City’s population was growing again. The ambulance service was in high demand with 9,166 calls for the year, causing the Hospital to add two additional ambulance cars to the service. The increase in demand put stress on the Accident Ward facilities, which opened in 1899. The following year, demand was even higher with 10,685 calls and 39,329 emergency cases.

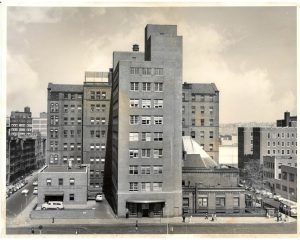

In 1947 friends of Dr. James I. Russell, a beloved and distinguished Roosevelt surgeon who had died in 1944, together with other friends of the Hospital, raised funds to construct a building to house modern accident and emergency facilities and a new surgical ward. Named the James I. Russell Memorial Building, the building featured a new, enlarged ambulance bay off 9th Avenue. The first floor handled emergency cases and the second floor was devoted to operating and treatment rooms for 46 surgical patients, and included X-Ray facilities, a plaster room, and eight observation rooms. The Hospital broke ground for the new building in August of 1948 and it opened in June of 1949.

The 1950s saw a continued expansion of the ambulance service and the upgrading and specializing of ambulance car models. In September 1956, three ambulances of a new design, made especially for metropolitan service by the Hospital Ambulance and Purchasing Department personnel, went into service. Their uniquely designed square bodies afforded room to carry four patients on stretchers, in double-decker fashion, or eight persons seated. Peter B. Terenzio, President and Director of the Hospital said the new design provided a ”functionally safe mobile unit which will permit more efficient patient care.” The new two-tone light gray ambulances were the gift of the J.P. Stevens Company, a textile concern, and the Theodore Luce Foundation.

In 1968 the Chief of Ambulance Services designed a new ambulance, for the Hospital. This ambulance, paid for with funds raised by the Hospital’s volunteer corps through the Generosity Thrift Shop, contained many life-saving devices, including an apparatus that provides vital anti-shock treatment while the vehicle is enroute from accident to Hospital.

By the 1960s automobiles were the standard mode of transportation, utilizing a growing system of roadways around the city as well as across the country. The increase in traffic provided an additional challenge to public health and safety. This problem was brought to national attention when President John F. Kennedy noted that, “Traffic accidents constitute one of the greatest, perhaps the greatest, of the nation’s public health problems.” In 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared that traffic accidents were, “…the neglected disease of modern society.”

In 1970 the National Highway Traffic Safety Act was adopted. Amongst several things, the Act standardized EMS training and urged the adoption of a single emergency number countrywide. Use of the 911 emergency number began in 1968, but was slow in gaining acceptance by every state. In 1973 the Federal EMS Systems Act was established, forming 300 EMS systems across the country, including NYC EMS, and the beginning of sweeping changes in EMS care and development across the country.

In the 1970s to 1990s, NYC’s EMS operated under the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, which dispatched both its own ambulances and hospital-owned ambulances. On March 17, 1996, NYC EMS merged with the Fire Department of New York (FDNY), forming the Bureau of Emergency Medical Services. FDNY EMS now controls the operation of all ambulances in the NYC 911 system, 70% of which are FDNY-based and 30% hospital-based, supplemented by private ambulance services.