Apr 27, 2021

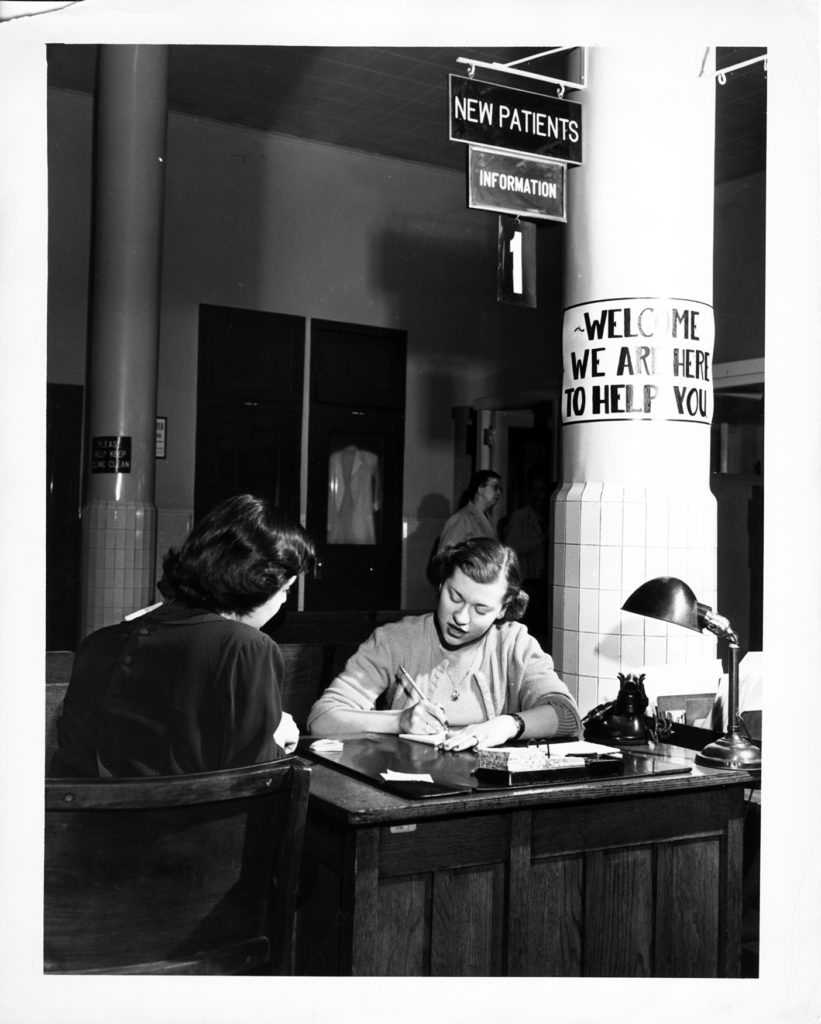

The Mount Sinai Hospital created its Dispensary/Out Patient Department in 1875 when it established four clinics: the Gynecology Clinic, the Children’s Clinic, as well as ones for Medicine and Surgery. Then as now, these clinics were designed to treat people with health needs that did not require a hospital stay. The Hospital traditionally had a long waiting list for admission, and this was seen as a way to help those they could before their conditions worsened. (In addition, in 1884, Mount Sinai Hospital created what it called the “Outdoor Visiting Physicians” to actually go to people’s homes to care for them there. Medicines were provided from the Hospital pharmacy.)

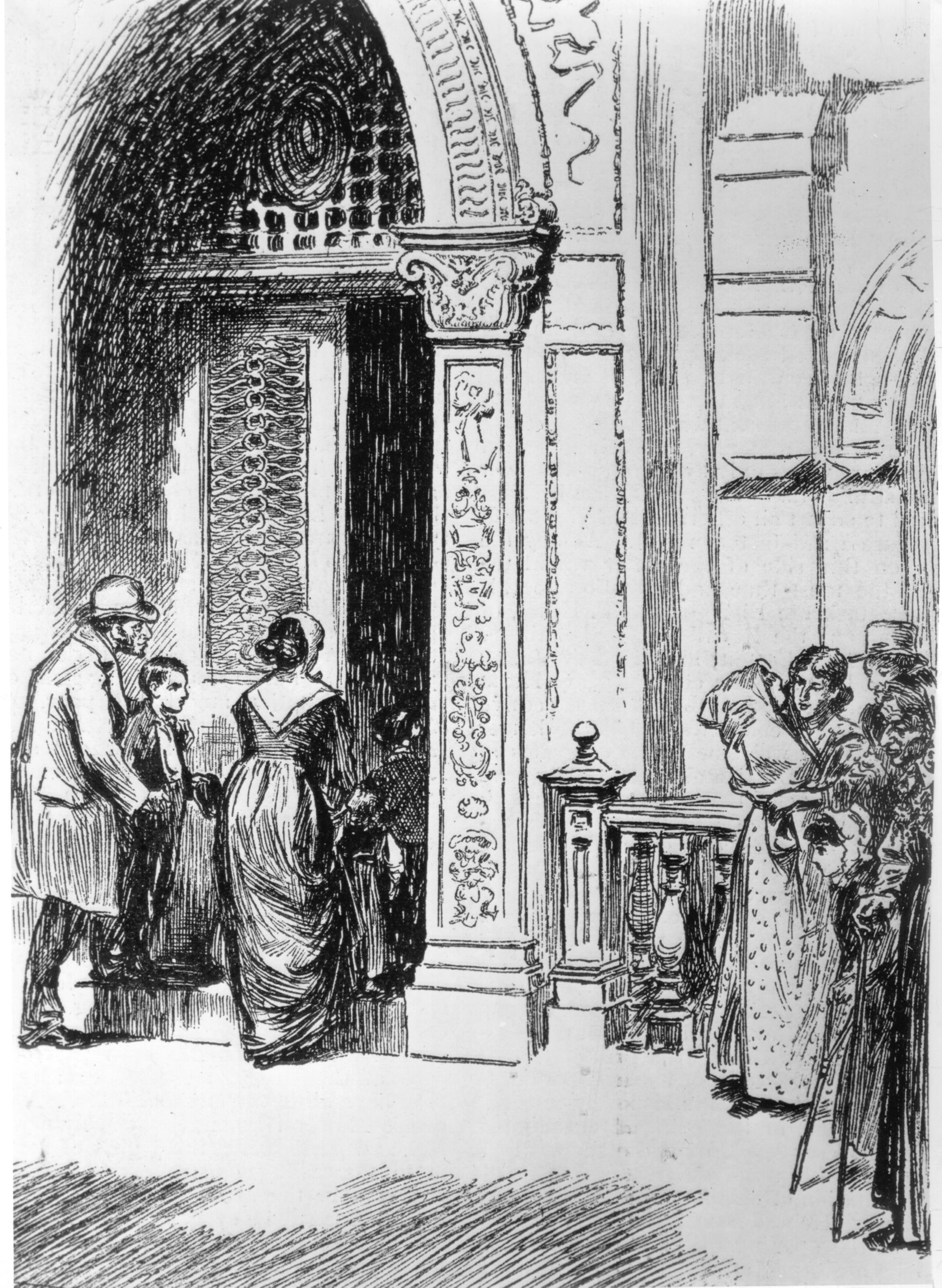

The Hospital was a charity organization and highly dependent on keeping costs down and maximizing donations to support its work. While there were a few patients willing and able to pay something for their care, the vast majority were treated free of charge both on the in-patient side as well as in the Dispensary. Since funds were so limited, Mount Sinai tried to take steps to ensure that their efforts were helping those most in need. One of those steps was to post a sign in the Dispensary that said, “Poor People Only Treated Here”. It eventually became clear that this sign was disrespectful to the people who used the clinic, and 140 years ago, on May 8, 1881, the Board of Directors of the Hospital decided to look into having the sign removed. Unfortunately, the Board minutes do not tell us if it was actually taken down.

The need to closely watch expenditures and try to reserve their services for the most needy continued to plague the Hospital leaders for decades. The beginnings of health insurance in the early decades of the 20th century helped, but it was really the implementation of Medicare and Medicaid in the mid-1960s that relieved hospitals of much of the burden of the costs of charity care.

The entrance to the MSH Dispensary, 1890

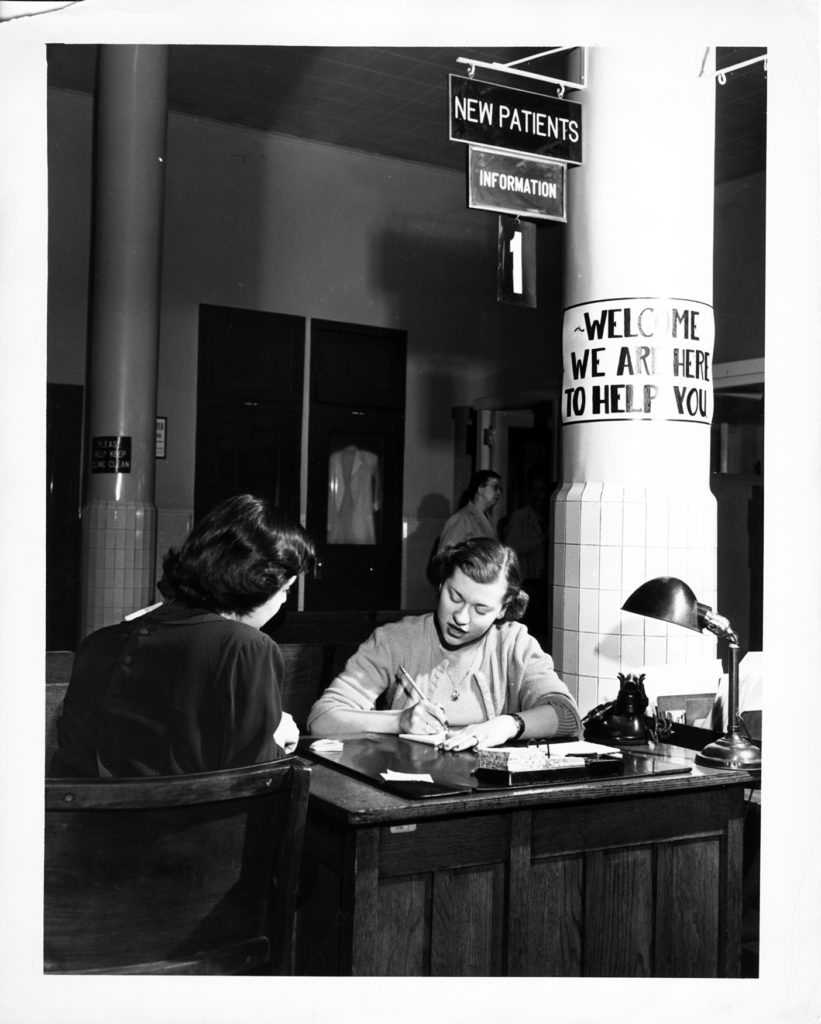

The Mount Sinai Hospital OPD Admissions desk in 1951

Apr 12, 2021

In today’s world, the only way to check into a hospital, without an emergency, is for a doctor to arrange for some kind of test or surgical procedure. But in the 19th century, hospitals functioned a bit like today’s walk-in clinics, at least in regards to admission. A person could come to the Hospital, speak with the Admitting Physician and request treatment for ‘X’ problem. But there were rules governing who would be accepted or refused.

By 1859, St. Luke’s published the first of their annual reports, which included reports from the Board President, The Pastor/Superintendent and the House Staff, along with lists of donations, occupations and diseases of those treated, and the publication of rules – for staff for patients and for visitors, and for Admission. Admission rules separated out patients with certain diseases. Those with contagious diseases were refused admission – this was a common practice for private hospitals at this time. The 1904 annual report is the first year the Hospital reported which applications were declined under the Rules of Admission, and their numbers. Ten persons were declined admission due to contagions like Erysipelas, scarlet fever and scabies.

Another group – the chronic or incurable – included paralytics, rheumatics, the mentally ill, incurable cancer patients, and those with an opium habit or delirium tremens, where also refused admission. Chronic cases in acute attack might be accepted, but were discharged once they returned to the ordinary health of one in that condition. Incurable cases might be admitted, but “only at the discretion of the Executive Committee of the Hospital.” These were also probably discharged as soon as they regained what was ordinary health for that condition. In 1904, 128 cases were refused admission to St. Luke’s for one of these reasons.

One exception to the rules was pulmonary consumptives (tuberculosis). In the 19th century, consumption was considered a hereditary disease, rather than a contagious one. The 1859 report of the Board of Managers, explains, “To provide for the incurably ill, particularly of this class, was one of the objects of the Hospital, and therein to supply an urgent want in the community… there was no resort for consumptives, so numerous in our climate, that St. Luke’s, as a church institution, felt bound to open to them her doors.“

The woman’s tuberculosis ward at St. Luke’s Hospital, circa 1900

The Pastor’s report often notes the comfort, and at times cure, these patients received, and their expressions of gratitude. In 1891, nine years after the discovery of the tubercle bacillus by Dr. Robert Koch, St. Luke’s accepted control over the House of Rest for Consumptives in the Tremont section of the Bronx, eventually moving all its patients to the main hospital and selling the property to support their care. Throughout the years annual reports note that consumptives made up to a quarter of the total census of patients in any given year.

These rules on admission disappeared early in the 20th century as hospitals’ ability to recognize and control germs was established, and as out-patient clinics opened to treat patients that might not have been admitted to the Hospital’s care in prior years.

Mar 26, 2021

Women have been active contributors to Mount Sinai Beth Israel since its founding in 1890. From the Ladies’ Auxiliary formed in MSBI’s first year of operation, to the first female House Staff member Dr. Nettie Shapiro in 1909, to so many on our front lines today, women’s contributions have always been essential to the operation of the hospital. This year for Women’s History Month, we’ll be featuring Dr. Marie Nyswander (1919-1986), a psychiatrist and an early leader in methadone maintenance in the treatment of heroin addiction.

Dr. Nyswander was born in Reno, Nevada, and graduated from Sarah Lawrence College (1941) and Cornell University Medical College (1945). From there she joined the Public Health Service in Lexington, Kentucky, where she first worked with patients with addiction issues. She later received psychiatry training at New York Medical College, and published a book, The Drug Addict As A Patient, in 1956. The book was among the first which argued for treating addiction as a medical problem, rather than a moral failing, likely influenced by the dramatic increase chemotheraputic treatments for psychiatric disorders in the 1950s. She went on to chair the New York City Mayor’s Advisory Board on Narcotics in 1959 and worked at a clinic in East Harlem throughout the early 1960s, alongside her own private practice.

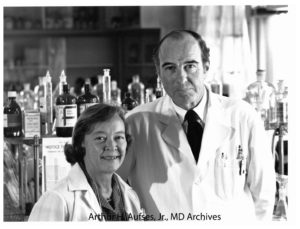

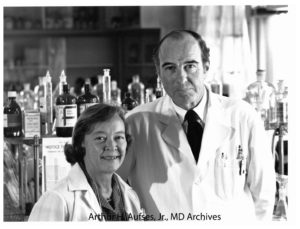

Photograph of Drs. Nyswander and Dole

In 1964, she was invited by Dr. Vincent Dole, a physician at Rockefeller Hospital, to join a study on the biology of addiction, which ultimately led to the discovery of methadone as a treatment for heroin addiction. Drs. Nyswander and Dole married in 1965. From the late-1960s until her death in 1986, she was affiliated with Beth Israel Hospital, where thousands were eventually treated through the Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program. She also served on the President’s Advisory Board for Mental Health during the Carter administration. Both she and her work with Dr. Dole received many honors.

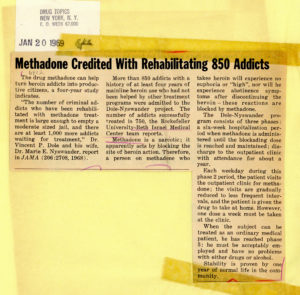

Article from January 20, 1969 issue of “Drug Topics”

Dr. Nyswander was a fierce defender of what has been a controversial treatment since its inception. Though detractors argue that methadone replaces one opioid addiction for another, Nyswander and Dole saw that abstinence-focused treatments were not always effective and that the symptoms of withdrawal caused by detoxification were needlessly challenging and painful for the patient. Methadone, an opioid itself, prevents drug cravings and blocks the ‘high’ of heroin.

Dr. Nyswander passed away in 1986 at the age of 67.

Sources:

Courtwright, David T., “The prepared mind: Marie Nyswander, methadone maintenance, and the metabolic theory of addiction,” Addiction 92, vol. 3 (1997): 257-265. Accessed March 23, 2021.

Dole, Vincent, Biographical photographs, Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

“Dr. Marie Nyswander Dies at 67; Expert in Treating Drug Addicts,” The New York Times (New York, N.Y.), April 21, 1986. Accessed March 23, 2021.

Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program clippings, AA088.S003.SS001.B003.F029 – AA088.S003.SS001.B003.F047, Mount Sinai Beth Israel collection, Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Mar 15, 2021

In April we celebrate both Women’s History Month and national Social Work Month. So it is fitting that we highlight a woman at Mount Sinai who was also a pioneer in social work, Miss Doris Siegel (1914-1971). Mount Sinai’s Department of Social Services (later Social Work) was created in 1907 and, since it was still a new field of service, the Department was initially managed by a series of nurses. By the mid-20th century, this was no longer the case, and in 1954, Doris Siegel was named Director of the Department. During her tenure, she updated and expanded the services of the Department, and spent time on broadening educational efforts in social work.

Doris Siegel, 1969

When Mount Sinai School of Medicine was forming in the 1960s, a new entity was created called the Department of Community Medicine (today’s Department of Environmental Medicine and Public Health). In 1968 the Social Services was moved into Community Medicine as the Division of Social Work. In this new role, the mission of Social Work was to support the School through innovative community service programs, research, and participation in medical student education. (They had been training nursing students from the beginning.) These were all activities that staff in Social Work had been doing for many years, and being an official part of the School supported and encouraged them to continue.

In 1969, social work at Mount Sinai as an academic enterprise was recognized with the creation of the Edith J. Baerwald Professor of Community Medicine (Social Work), the first endowed chair in social work in an American school of medicine. (It was a gift of Jane B. Aron, a Trustee at Mount Sinai and a long-time supporter of Mount Sinai’s Department of Social Work.) Doris Siegel was installed in the chair at a special convocation ceremony in 1969, making her the first woman named to an endowed chair at Mount Sinai. She died two short years later, but is still remembered today as a “Pioneer in Social Work.”

The Baerwald Chair remained in the Division of Social Work through the tenure of two more Directors, Helen Rehr and Gary Rosenberg. Meanwhile, the broader Department had evolved and changed its named several times. In 2017, the Baerwald Chair in Social Work became the Baerwald Professor of Environmental Medicine and Public Health.

Mar 1, 2021

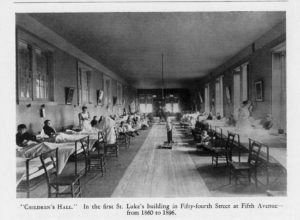

When St. Luke’s Hospital was in the planning stages, it was Rev. Muhlenberg’s wish that the Hospital maintain a mission of charity, and that no suitable applicant be turned away, regardless of his or her ability to pay for treatment. The wards for men and women were designed with large windows to allow in sunshine and fresh air, as it was felt that these elements, along with good food, were essential for providing a cheery atmosphere in which to recover good health.

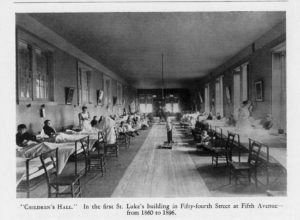

However, the Managers soon realized a need they had overlooked: the number of sick children needing treatment. The 1860 annual report notes that one of the smaller rooms was set up as a Children’s Hall, to separate youngsters from the adults, which makes sense, as they probably needed more attention from the nursing staff.

However, the Managers soon realized a need they had overlooked: the number of sick children needing treatment. The 1860 annual report notes that one of the smaller rooms was set up as a Children’s Hall, to separate youngsters from the adults, which makes sense, as they probably needed more attention from the nursing staff.

The Trustees’ report for 1865 lists two big wants: “more room for sick children, because the apartment given them is always more than full” and “a ward for boys above the age of childhood, who are now mixed with adults, but in view of their moral interests, ought to be separate.” Judging by later reports, this may have been for boys below the age of 15 years. Annual reports list as many as 150 children needing care a year.

Many of the children brought to St. Luke’s had orthopedic problems, particularly hip joint diseases, and spinal issues. The first specialty services established at St. Luke’s was Orthopedic Surgery, opened primarily to treat pediatrics patients such as these. However, the mission of the Hospital was to treat and heal, and these cases often required prolonged rehabilitation on-site. The Board of Managers reached out to Hospital benefactors for solutions.

In 1868, the Hospital received the gift of a country estate in King’s Park, Long Island, courtesy of Mrs. C.L. Spencer and her niece Miss Wolfe. Called St. Johnland, it was a convalescent home for crippled or disabled children and many of the children of St. Luke’s went there to rehabilitate, recuperate, and enjoy the fresh air and sunshine of the country environment. Later annual reports note that children at St. Johnland did the typesetting and printing of these reports, which suggests that some children had trade training, perhaps so they could earn a living once they were discharged from Hospital care.

Another concern of Rev. Muhlenberg and the Board of Managers was care for the infirm elderly, especially elderly men with no family. Part of St. Johnland became a nursing home for them, answering both concerns. St. Johnland functioned as a rehabilitation home for children until the early 1950s, when its Board of Trustees decided to focus on the elderly population exclusively. St. Johnland still functions as an elder care center today.

In the mid-1880s to mid-1890s, a large summer cottage in Great Neck, Long Island was made available to St. Luke’s as a convalescent home by the generosity of Mrs. And Mrs. Edmund C. Stanton. Sick children from the Hospital spent their summers there, away from the heat and closeness of the city with accompanying nurses. A Hospital Attending made weekly visits to check on the children. Other summer homes were loaned to St. Luke’s for use as convalescent homes from time to time.

In 1925, Mrs. Hicks Arnold donated her estate of several hundred acres in Greenwich, Connecticut, called Byram Woods, to St. Luke’s Hospital. It came with an additional one million dollars for the construction of a convalescent hospital and the establishment of an endowment for its upkeep.

The Byram Hills Convalescent Home opened in 1927 and provided a healthy place to recuperate in a country setting, with the requisite fresh air and sunshine for hundreds of children. As times, and medical practice, changed and the Byram Hills facility aged, it eventually became outdated. In November 1964 Byram Hills was closed and sold.

However, the Managers soon realized a need they had overlooked: the number of sick children needing treatment. The 1860 annual report notes that one of the smaller rooms was set up as a Children’s Hall, to separate youngsters from the adults, which makes sense, as they probably needed more attention from the nursing staff.

However, the Managers soon realized a need they had overlooked: the number of sick children needing treatment. The 1860 annual report notes that one of the smaller rooms was set up as a Children’s Hall, to separate youngsters from the adults, which makes sense, as they probably needed more attention from the nursing staff.