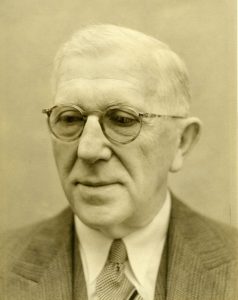

The Mount Sinai Doctor: Isidor C. Rubin

This is the first in a series, The Mount Sinai Doctor, that are adapted from the thorough biographical entries located in our Archives catalog, information gathered from This House of Noble Deeds: The Mount Sinai Hospital, 1852-2002, and the unpublished unique material stewarded in our Archives.

Isidor Clinton Rubin was one of the exemplars of what it means to be a Mount Sinai doctor. His unceasing efforts to improve patient care and outcomes through research, innovation, and clinical application changed our understanding of infertility in women. Many couples who were struggling to conceive children sought out Dr. Rubin for his expertise.

He is best known for inventing what is called the Rubin Test, which determines the patency (degree of openness) of the fallopian tubes. The test consists of insufflating a gaseous medium (originally oxygen, later changed to carbon dioxide) into the uterine cavity. If the tubes are blocked, sterility results. Rubin performed the first test on November 3, 1919 at The Mount Sinai Hospital.

Prior to the development of the Rubin Test, doctors could only test patency with any certainty by performing a surgical procedure called a laparotomy. In other cases, where the tubal factor had not been explored, other operative procedures were used to relieve sterility when, in fact, the problem was due to closed fallopian tubes. In sum, the Rubin Test reduced the number of surgical procedures needed to diagnose and treat sterility in women. It also had therapeutic value in that it relieved some cases of dysmenorrhea (severe pain associated with menstruation) and sometimes facilitated conception. He was also among the first to apply x-rays in the practice of gynecology, and undertook work on carcinoma of the cervix, uterine Endoscopy, and ectopic pregnancy.1

Born in 1883, he attended the College of the City of New York and graduated from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University in 1905. For the next three years, he served as an intern and then a resident at the Mount Sinai Hospital.

In 1909, Rubin, along with Dr. Abraham Hyman, went to Europe for additional post-graduate training, like so many others of his time.

He traveled in Austria and Germany and studied with Professor Julius Schottlander, Pathologist of the II Universität Frauenklinik in Vienna. Upon his return to the United States, Dr. Rubin set up a private practice and took appointments on the Gynecology staffs at Mount Sinai, Montefiore, and Beth Israel. He also worked at the Harlem Hospital for some years.

Another quality so common to the great Mount Sinai doctors is a dedication to advancing medical education; he held a clinical faculty appointment on the Gynecology staff of the College of Physicians and Surgeons from 1937-1947 and taught at the New York Medical College and New York University medical school.

However, it was truly to Mount Sinai Hospital which he devoted “his schedule and energy rising through the ranks to become Attending Gynecologist and, eventually, Chief of Service from 1937 to 1945.”2 The Mount Sinai Hospital’s Gynecological Department was established 145 years ago in 1877 by Dr. Emil Noeggerath. While today Mount Sinai has the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Science, Rubin’s tenure in the “Gynaecological Department” was before the addition of an Obstetrics services. Spanning the first half of the 20th century, he worked during the period when doctors were advocating to add Obstetrics to the Hospital’s services (see Giving Birth to an Obstetrical Service for more information). When Dr. Rubin retired from active service in 1945, he continued his affiliation by remaining on the Medical Board and transition to being a Consulting Gynecologist.

A consummate hallmark of a Mount Sinai doctor, he was very involved in outside professional activities throughout his career. In 1928 he served as President of the New York Obstetrical Society. He was a founding member of the American College of Surgeons and the American Board of Obstetrics. In 1955-56, he was the President of the American Gynecological Society. He also helped edit the International Journal of Fertility, Fertility and Sterility, Gynécologie Pratique, and the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

The advances made by his work were lauded the world over, and he received many awards over his life. He was elected a Fellow of the American Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Gynecological Society and the New York Obstetrical Society. In 1947, he won the ORTHO Award, and received the rank of Chevalier in the French Legion of Honor. In 1954, he became Officier of this group. He was awarded honorary degrees from the University of Athens in 1952 and the Sorbonne in 1955. In 1957, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists awarded him an Honorary Fellowship. His alma mater, the College of the City of New York, chose him for their Distinguished Alumnus Award.

Dr. Isidor Rubin married Sylvia Unterberg in 1914. He died while at a conference in London on July 10, 1958, and was survived by three children, Dr. Harvey N. Rubin, Carol R. Meyer, and Edith R. Fishel.

The two collections in the Aufses Archives that document his work provide an insight into a physician constantly seeking the answers to the unknown in order to understand and treat gynecological ailments. There are also materials related to Dr. Rubin in other collections.

The Isidor Clinton Rubin, MD case history files and manuscripts contain the patient files created by I. C. Rubin in his private medical practice. They relate to his work in infertility and other gynecological areas. Access is restricted to the case records due to the presence of HIPAA-protected Personal Health Information. Open to research, the Isidor Clinton Rubin, MD papers contain an array of materials, letters, notebooks (such as the two pages from one entitled Cases, Experiments, Questions depicted below), ephemera, awards, and photographs documenting the life’s work of one of the quintessential Mount Sinai doctors.

- 1.Collected papers [reprints] of Dr. I.C. Rubin, 1910-1954. Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives Catalog. https://archives.mssm.edu/aa090-s001-f101

- 2.Aufses, Jr. MD A, Niss B. This House of Noble Deeds: The Mount Sinai Hospital, 1852-2002. NYU Press; 2002.

Authored by J.E. Molly Seegers