See Building Beth Israel, Part 1: Foundations and Part 2: Jefferson and Cherry for the first parts of this series. An interactive map of Beth Israel historical locations is available here.

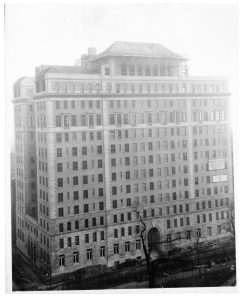

Photograph of Dazian exterior, circa 1930

The final years at Beth Israel Hospital’s Jefferson and Cherry Streets location were marked by some of the most defining moments of the early twentieth century. While it’s not clear exactly when conversations in favor of a new hospital began, the Beth Israel Board of Directors began to purchase property on Livingston Place along Stuyvesant Square Park as early as 1915. (Livingston Place would later be renamed Nathan D. Perlman Place after the U.S. Congressman and Beth Israel Vice President.)

A primary motivation for the creation of what would become the Dazian Pavillion was likely related to hospital capacity – the thirteen-story building opened with nearly 500 private rooms and state-of-the-art facilities, a significant expansion over the 134 beds in wards at the Jefferson and Cherry Streets location. That said, justifications for the new building from the Board of Directors evolved from its earliest phases and its final construction in 1929. These reflect the many historical events of the era: modernization of health care, the introduction of the skyscraper, World War I and its aftermath, mass immigration, and the Influenza Epidemic of 1918.

The Tallest Hospital Building in the World

The Dazian Pavillion was conceived as a highly modern, state-of-the-art hospital building. At thirteen stories, it was the tallest hospital building in the world at that time. According to Islands of Compassion, Beth Israel “was the first to realize that a hospital skyscraper would mean freedom from the city’s noise and congestion.” This is evident in the discussions in the Board of Directors minutes. From March 16th, 1919:

It is of great concern to us to construct the new hospital according to the best methods of building; to provide the patients with as much comfort as possible, to serve them with palatable food, to provide them with fresh air and sunshine, to guard them from undue noise and excitement, and to keep the patient away from the smell and the workings of the Hospital – in a word, we are studying how best to care for the patient…The hospital of the future must be organized for prevention and not so much for cure.

World War I and its Aftermath

World War I was strongly felt at Beth Israel Hospital, with nearly half of the medical staff enlisted in the war effort. This continued throughout the war and beyond its end, and care for veterans presented itself as an early justification for a new hospital building. From the November 18, 1917 Board of Directors minutes:

The War presents the strongest argument for the construction of the new building. The War will last for some time and it is absolutely certain that there will be a great demand for hospital accommodation especially on account of the draft; deformities and disabilities are being discovered which require doctoring and good hospital care. The Beth Israel Hospital will be the only institution in the City to come up to expectations. We must be ready to receive cases on account of the epidemic that will surely follow the War and the new Hospital should stand as a permanent monument.

Beth Israel’s service to those affected by the war did not end with veterans. From the Board of Directors Minutes, October 17, 1920:

Congressman Siegel informed me that there are 200,000 Jews trying to secure passports for the United States. Orthodox Jews from Syria and Greece will come here in large numbers. That there are 15,000 Jews at Danzig awaiting transportation. If there is any doubt at all in the minds of anyone as to the necessity of a 500 bed Beth Israel Hospital for the treatment of Orthodox Jews this statement of Congressman Siegel should dispel them.

If Beth Israel was founded to care for Jewish immigrants in New York, the events following World War I only strengthened this resolve.

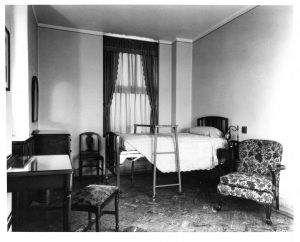

Influenza Pandemic of 1918

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918 was also a justification for the layout of the new building. The need for private rooms was a strong topic of debate in the years leading up to construction, within both the Board of Directors and the medical profession, considering hospitals largely operated out of shared wards at this time. The pandemic cemented the need for private rooms. From the Board of Directors Minutes, November 23, 1919:

…in respiratory infections…protection can only be obtained by safe-guarding one person from another, that the lesson derived from the severe experience of the recent Pneumonia epidemic is to the effect that such patients are not to be assembled into larged [sic] groups or kept in open wards but should be kept in separate rooms where they and their attendants may be preserved as far as possible from sputum droplet contamination.

Private room at Dazian Pavillion, circa 1930.

The Dazian building would come to feature almost entirely private rooms.

Conclusion

Dazian Pavillion cornerstone laying ceremony, November 1922.

Ultimately, the Dazian Pavillion took more than a decade to come to fruition. While many of the buildings and lots for the future space were purchased throughout the 1910s, there was significant slowdown in building progress due to the influenza epidemic. Building materials were also more expensive due to World War I.

On November 5, 1922 the cornerstone was laid. The ground was broken by Isaac Phillips, and future President Herbert Hoover, then U.S. Secretary of Commerce, were in attendance. The architect for the Dazian building was Louis Allen Abramson.

The building was finally opened in 1929. The Beth Israel Hospital School of Nursing (today the Phillips School of Nursing at Mount Sinai Beth Israel) moved into the 6th and 9th floors. Nearly 100 years after construction began, Dazian continues to be the home of Mount Sinai Beth Israel today.

Sources:

- Beth Israel Board of Directors minutes, 1914-1915

- Beth Israel Board of Directors minutes, 1915-1924

- Levitan, Tina. Islands of compassion, a history of the Jewish hospitals of New York. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1964.

- Mount Sinai Beth Israel photograph collection

- Phillips School of Nursing Yearbook, 2005

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist