Feb 21, 2018

Soon the Match will be upon the fourth year class and after months of deciding on a field, debating on various institutions, filling out paperwork and then smiling bravely through interviews, the new doctors will be on the resident staff of a hospital. This complex system of ‘matchmaking’ began in 1952 and replaced the practice of individuals applying to various residency programs, perhaps being measured against changeable and very subjective criteria.

In the early years of the 20th century, The Mount Sinai Hospital had in place a rigorous testing program to help winnow the number of applicants, leaving the ‘best and the brightest’ to face additional testing. Each year several hundred medical students would sit for the examinations that would lead to the selection of the twelve newest members of the house staff. The first day’s written examination was number coded, with the individuals’ names hidden so favoritism could not occur. The next day, the top scores were posted, and the 60 highest scorers would return for oral exams given by the medical staff. The questions were broad and usually designed to show a wide knowledge in the basic sciences and clinical medicine, as well as critical thinking skills. Questions on art or literature were not unknown, depending on the faculty member’s interests. The exam evolved over time to be more rigorous, and eventually recommendations from medical schools deans were also sought.

In 1930, these were some of the written questions the applicants were posed. How would you do?

1. In what stages of the following diseases would you terminate early pregnancy? a. Tuberculosis of the lungs b. Nephritisc. Diabetes d. Valvular heart disease

2. Under what conditions would you select for anesthesia? a. Chloroform b. Ether c. Nitrous oxide d. Spinal e. Local f. What special contra-indication for each?

3. In what illnesses may the joints be involved?

4. In what extra abdominal conditions may abdominal symptoms appear?

5. A patient has been operated upon for an acute gangrenous appendicitis with abscess. He had one chill prior to operation. Post-operative course is marked by fever of 102 to 104; high leucocytosis; polynucleosis. X-ray examination of the chest and right hypochondrium shows moderate elevation of right diaphragm. Discuss possible causes of the high temperature.

Jan 16, 2018

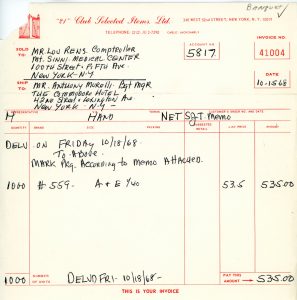

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Classes began on September 9th, and on October 20, 1968 there was a day-long celebration to dedicate the School and inaugurate Dean George James, MD as the first President of The Mount Sinai Medical Center. As part of this special day, there was a colloquium in the morning with four Nobel Prize laureates speaking about the future of medicine. (The papers presented by the speakers were later published in the Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. They are available here.) In the afternoon there was the dedication of the School and the inauguration of Dr. James. In the evening there was a banquet held at the Grand Ballroom at the Hotel Commodore.

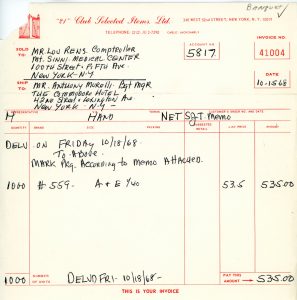

Cigar order for the Dedication Day banquet

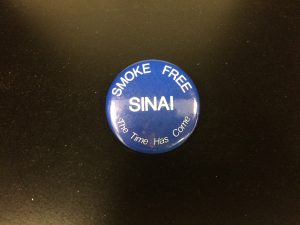

The Aufses Archives has several files about the planning and creation of this big event and how it all came together over a few short months. No detail was too small for the organizers to organize, as evidenced by an invoice for 1,000 cigars to be sent to the hotel from the 21 Club (founded by the brother of Mount Sinai Trustee I. Robert Kriendler). Today we would be shocked if a hospital passed out tobacco products but the 1960s were a different time. Still, already the tide was turning. In March of 1968, the Trustees’ Executive Committee had voted 8 to 5 to ban the sale of cigarettes at Mount Sinai, but it was not until 1989 that areas of the Hospital started to be designated as smoke free. This was the result of action by the Student Council of the School, with the support of the Dean’s Office, and then working with the Hospital administration and the Medical Board. What was seen by some at the time as difficult to implement is now viewed as a simple idea whose ‘time had come.’

A button created by Mount Sinai students to encourage the institution to go smoke free, 1989

Dec 8, 2017

In October of this year, The Mount Sinai Hospital announced the opening of the new cardiac unit, the former Cardiac Care Unit (CCU), now located on KCC 6 in the Klingenstein Clinical Center. There are 20 beds, ten of which are the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (CICU) and ten are step-down beds, the Cardiac Step Down Unit (CSDU). Unlike the other ICU units, the ten ICU beds are all private rooms. The entire unit is beautiful, with a receptionist desk as you get off the elevator.

It just so happens that last year, the Aufses Archives received a small set of papers from Barbara McPeek Mulhearn, RN, Class of 1962 of The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing. Among those items was information about Mulhearn’s role in creating the first Cardiac Care ICU at the Hospital, which opened in 1968. Her title was Assistant Nursing Supervisor in charge of the Ames Coronary ICU, an eight bed unit on the 4th floor of KCC. The Unit opened February 19, 1968.

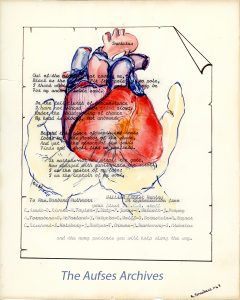

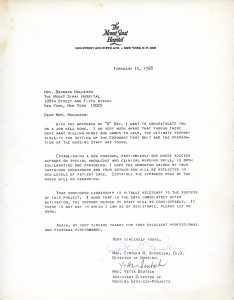

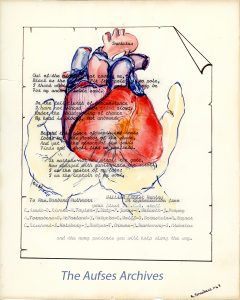

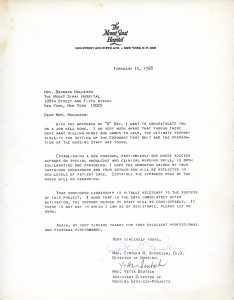

Shown below are two pieces from the collection: a drawing of a heart held in a person’s hands with the poem “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley typed over it. This was sent to Mulhearn from “her first I.C.C.U. staff,” in appreciation from them “and the many patients you will help along the way.” Also shown here is a letter from Dr. Cynthia Kinsella, the Director of Nursing at The Mount Sinai Hospital at the time, thanking Mulhearn for her efforts and encouraging her as they neared the Unit opening.

Fifty years on, the caring legacy continues.

Sep 29, 2017

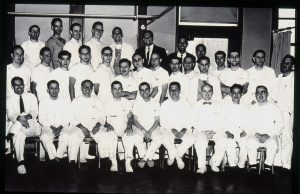

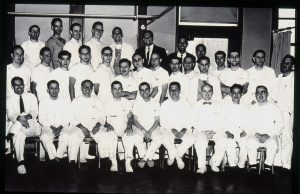

As the repository for the historical records of the seven Mount Sinai Health System hospitals, the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives has an extensive collection of historical photographs, many of which are available to view in our Image Database. Sometimes, however, the photographs in our collection have no information that would give them context. These photographs of the Beth Israel Medical Center house staff in the 1950s and 1960s arrived at the Archives as part of an unorganized collection of slides that we have been hard at work arranging and cataloging. While we can tell that they are photographs of the house staff, and can recognize that most of them were taken on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion, we don’t know the names of any of the doctors. Do you? If so, contact the Archives and let us know!

The 1958 Beth Israel house staff on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion

The 1958 Beth Israel house staff on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion

The Beth Israel house staff of an unidentified year (early 1960s?) on a hospital ward

The Beth Israel house staff of an unidentified year (early 1960s?) on a hospital ward

The Beth Israel house staff of an unidentified year (late 1950s?) on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion

The Beth Israel house staff of an unidentified year (late 1950s?) on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion

The Beth Israel house staff of an unidentified year (early 1960s?) and other Beth Israel doctors/administrators on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion

The Beth Israel house staff of an unidentified year (early 1960s?) and other Beth Israel doctors/administrators on the roof of the Dazian Pavilion

Jun 8, 2017

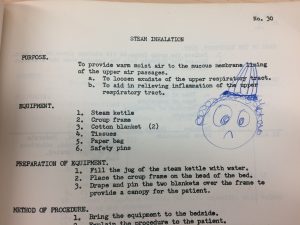

The Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives recently received a copy of the 1957 Mount Sinai Nursing Department Manual of Nursing Procedures from Gail Singer Lyon, member of the Class of 1962 of The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing. Manuals like these have value because they show what the patient experience and medical care were like then, and they provide a sense of what the duties of a nurse were at a given point of time. The Archives has many such manuals from 1931 up to the present day, and they provide great information on how nursing, medicine, and hospitals have changed over this span.

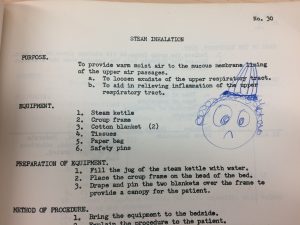

While the Archives has other copies of this edition of the Manual, what makes this copy special are the extras that Ms. Lyon has included with her volume, from inserts to doodles. The manuals were given to the students to govern their practice when they were in the clinical areas of the Hospital. It includes detailed instructions on everything from Abdominal Binders to Wall Suction, Method of Using. Throughout the Manual, when it is necessary to provide examples using the names of doctors, the procedures referred to them as Dr. Roe and Dr. Moe. The patient is, of course, John or Jane Doe. Ms. Lyon wrote hints and additional information on the pages of her volume, and also inserted forms and updates to the policies.

This post highlights some of those ‘extras’ that make this volume interesting.

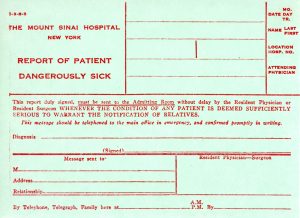

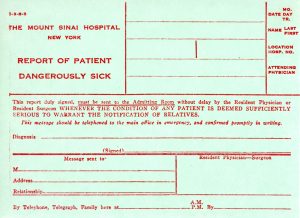

This form shows the communications technology of the time. Note the bottom row for how a family would be reached in time of emergency.

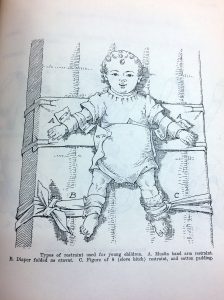

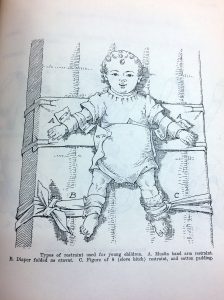

A lovely drawing showing how to restrain a child

A doodle, clearly showing a woman wearing a Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing cap, with is many pleats in the front.

May 8, 2017

On April 26, 2017, the Mount Sinai Archives celebrated its dedication as The Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives. This re-naming was in grateful recognition of the long-time support and dedication of Dr. Arthur Aufses and Mrs. Harriet Aufses. The Archives houses historical collections from the Icahn School of Medicine and the seven hospitals within the Mount Sinai Health System, with collections comprised of paper records, photographs, artifacts, memorabilia, and digital records—measuring 2,700 linear feet of history. The oldest records date to the 1840s and new records – paper and electronic – are added every day. The hospitals represented in the collection are: The Mount Sinai Hospital, Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s Hospital (including the Woman’s Hospital), Mount Sinai West (formerly the Roosevelt Hospital), Mount Sinai Queens, Mount Sinai Brooklyn, and the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai.

On April 26, 2017, the Mount Sinai Archives celebrated its dedication as The Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives. This re-naming was in grateful recognition of the long-time support and dedication of Dr. Arthur Aufses and Mrs. Harriet Aufses. The Archives houses historical collections from the Icahn School of Medicine and the seven hospitals within the Mount Sinai Health System, with collections comprised of paper records, photographs, artifacts, memorabilia, and digital records—measuring 2,700 linear feet of history. The oldest records date to the 1840s and new records – paper and electronic – are added every day. The hospitals represented in the collection are: The Mount Sinai Hospital, Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s Hospital (including the Woman’s Hospital), Mount Sinai West (formerly the Roosevelt Hospital), Mount Sinai Queens, Mount Sinai Brooklyn, and the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai.

For additional information about The Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives, please contact the staff at msarchives@mssm.edu. The Aufses Archives are a part of the Academic Informatics and Technology area, which includes the Gustave L. and Janet W. Levy Library, the Instructional Technology Group, and Academic and Research IT Systems and Support.

Apr 17, 2017

Nurses and doctors of St. Luke’s Hospital Evacuation Hospital No. 2

April 2017 is the 100th anniversary of the entry of the United States into World War I. Like many institutions in American society, the American hospital system and its doctors and nurses were rapidly mobilized to join the war that had been raging in Europe since the summer of 1914. The Mount Sinai Archives has now installed a display in the Annenberg Building north lobby outlining the activities of the hospitals in the Mount Sinai Health System.

In New York City, The Mount Sinai Hospital, St. Luke’s Hospital and The Roosevelt Hospital (today’s Mount Sinai West) all contributed to the war effort by establishing overseas units affiliated with their respective hospitals, and many doctors at Beth Israel Hospital volunteered individually. The records, photographs and correspondence on display in these cases reflect the experience of a war that defined a generation.

For the medical officers and administrators in charge of overseas hospital units, organizing effective hospital service on a scale never before seen was an immense logistical challenge. And for the individual doctors and nurses working with patients, who saw at close hand the terrible destruction inflicted by new methods of trench warfare and aerial combat, all while dealing with a world-wide pandemic of influenza, the war was an experience of medicine at its most fundamental, as they struggled under harsh conditions to relieve human suffering.

The items on display include images of the staff from the hospitals in their World War I roles; a scrapbook from Marion Moxham, a nurse from Ireland who joined with the Mount Sinai unit, Base Hospital No. 3; letters home from physicians to the Beth Israel Hospital administration; dog tags; a medal that was awarded to members of the Mount Sinai unit; images of the wounded and wards of St. Luke’s Evacuation Hospital no. 2 and a photo of the mascot of the Roosevelt Hospital group.

Feb 14, 2017

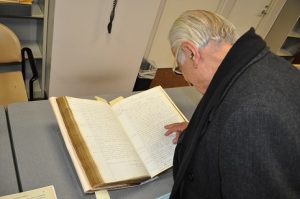

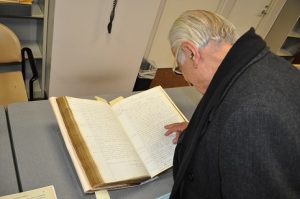

On February 7, 2017, the Mount Sinai Archives presented a program called “Treasures from the Mount Sinai West Historical Collections.” Mount Sinai West’s library was host to this historical exhibit featuring materials from the early Roosevelt Hospital collections, coupled with a description and historical context provided by archivist, Michala Biondi. The exhibit featured original photographs, ledgers, and artifacts highlighting various stages in the establishment and growth of Roosevelt Hospital. The talk started with a brief biography of founder James Henry Roosevelt (1800-1863) who intentionally led a frugal lifestyle in order to build a trust of nearly one million dollars to establish a hospital for the sick and diseased poor of the city.

Items on display included the Hospital’s first patient case register (1871-1873), an employee log from the 1890’s, the brass plaque commemorating the laying of the original complex’s cornerstone in 1869, a bound volume of the first five annual reports of the hospital and pamphlets describing the early plans for building and staffing the hospital, items highlighting the establishment of the Roosevelt Hospital nursing school, open from 1896 to 1974, and its growth during the first decades, and material describing and documenting Hospital employees’ experience as part of a hospital unit during WWI and an evacuation unit during WWII.

The employee log was of particular interest as it listed position titles and earnings, with occasional comments about the employee. Ms. Biondi noted that after the plant engineer, whose salary was listed as “one thousand dollars per annum with meals,” the highest paid employees were the Directress of Nurses, who earned $60 per month, and the bookkeeper and operating room nurses, who each earned $50 a month. Other positions included baker, firemen, stablemen/driver, orderly, laundress, office or errand boy, and private duty nurses. These positions’ salaries ranged from $40 per month to $3 per day, in that order.

The patient case book generated interest among several MSW doctors who came by to view the exhibit. Ms. Biondi highlighted a few of the patient cases, including a stone worker’s accident resulting in a leg amputation at the knee, and an infection of a finger that progressed throughout the arm and led to the patient’s death. Another case, described as a cerebral hemorrhage, was determined by a doctor who was present to more probably be a stroke, after reading the details of the description. Everyone remarked over the very neat and legible 19th century handwriting.

A group of almost thirty guests came to view the event, including MSW President, Dr. Evan Flatow, who was happy to see Hospital materials on display. The Archives staff was very pleased to be able to bring the Hospital’s history to life for all attendees.

Nov 30, 2016

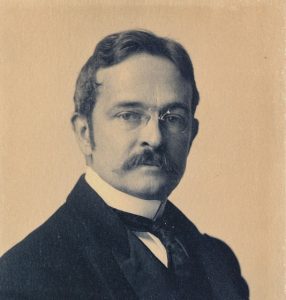

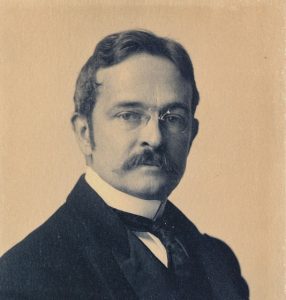

Robert Abbe (1851-1928) was a surgeon and pioneer radiologist in New York City. He was born in lower Manhattan and educated in NYC’s public schools. He attended the College of the City of New York (S.B., 1870) and Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons (M.D., 1874).

Abbe was best known as an innovative plastic surgeon, particularly for developing a procedure for repairing hair lip deformities (now commonly known as the Abbe Flap), and for  pioneering the use of radium as a treatment for various medical conditions. His many published articles document the breath of his surgical experience and the successes he had using radium to treat patients.

pioneering the use of radium as a treatment for various medical conditions. His many published articles document the breath of his surgical experience and the successes he had using radium to treat patients.

He served as a surgeon at the New York Hospital, St. Luke’s Hospital, Roosevelt Hospital, and the New York Babies Hospital, and was also a professor of surgery at the Women’s Medical College of New York, The New York Post-Graduate Medical College, and the College of Physicians and Surgeons.

In his free time, Abbe enjoyed drawing, painting oil portraits, and watercolors, and the emerging art of photography. During his later years he spent summers in Bar Harbor, Maine where he developed an interest in the Native American population of the area. He began collecting Native American tools and artifacts that he found in the area and in Stone Age relics he found on Mount Desert. He dreamt of creating a museum to display his extensive collection, and raised funds to do so. Unfortunately, he did not survive to see his dream fulfilled; the museum, which carries his name and still operates, opened a mere five months after his death of anemia at age 77, most likely due to handling radium.

A small collection of his papers and many reprints of his articles are open to researchers at the Mount Sinai Archives. The collection guide is available on the Archives web site, http://icahn.mssm.edu/about/ait/archives/collection/robert-abbe.

Nov 4, 2016

(This post was written by Nancy Mary Panella, Ph.D., Archivist Emeritus, St. Luke’s and Roosevelt Hospitals)

James Henry Roosevelt, whose bequest founded the Roosevelt Hospital, was the son of James Christopher Roosevelt (1770-1840) and Catherine Byvanck Roosevelt (1773-18??). He was also a distant cousin of President Theodore Roosevelt.

James H. Roosevelt

James Henry was born at his family’s home on Warren Street in lower Manhattan on November 10, 1800. Following his earlier education in neighborhood schools, he enrolled in Columbia College, where his studies included law, and was graduated from there in 1819. He subsequently set up a law practice in New York City.

With his studies behind him, and his law practice established, he stood on the threshold of a promising life: Described as a young man of pleasing appearance, brown hair, above-average height and with a gentle and courteous demeanor, he was well-to-do, brilliant, and engaged to be married to Julia Boardman, who was from an old New York City family.

But, suddenly, an illness that left him physically disabled struck, ending his plans for both career and marriage. The exact nature of the illness is unclear: Some speculated that it was lead poisoning from a home remedy for a cold, concocted of hot milk into which lead shot had been boiled. Others think he fell victim to poliomyelitis.

In any case, largely incapacitated, he abandoned his law practice. Not wanting to ‘burden’ Julia Boardman with his disability, he broke his engagement to her. (Neither married and both remained lifelong friends; in fact, one of the few bequests he made, outside of the one to his nephew, James C. Roosevelt Brown, and the monies left to found The Roosevelt Hospital, was an annuity for Ms. Boardman, whom he also named as executrix of his will.)

James Henry then embarked on a life not just of physical limitations, but also of frugality and austerity, devoting much of his time and interests to real estate dealings and to the management of his securities; he thus increased his worth substantially. It is thought that he conserved and increased his funds for one specific purpose: to support “the establishment in the City of New York of an [sic] hospital for the reception and relief of sick and diseased persons.” Whatever the reason, when he died in 1863, he left in excess of one million dollars toward that objective.

The hospital to be founded under the terms of his will was to be a voluntary hospital that cared for individuals regardless of their ability to pay. It seems reasonable to suppose that having himself suffered from illness, he realized the plight of those who might at the same time be afflicted with both sickness and destitution.

It is said that James Henry was never morose or gloomy. He maintained an active interest in the life about him and in the affairs in which he could not participate. He enjoyed the companionship of a host of friends, one of the closest being Julia Boardman.

Although James Henry Roosevelt’s remains were first buried in his family’s vault in the New York City Marble Cemetery, they were moved to the Roosevelt Hospital grounds when a monument to him was placed there in 1876. Moved twice again on the hospital grounds (hospital expansion required the moves), in late 1994 his remains were exhumed, and in the spring of 1995 re-interred in the New York City Marble Cemetery. Julia Boardman’s remains were interred in the same cemetery, but in her father’s vault.