Oct 18, 2016

New York Times, January 24, 1917

On October 16th, Planned Parenthood of New York reached its 100th anniversary. It grew from a small birth control clinic created in Brownsville, Brooklyn by Margaret Sanger, her sister Ethel Byrne, and Fania Mindell. At the clinic, they distributed birth control, as well as pregnancy planning advice and information. Even though the three women were arrested for distributing obscene material and jailed, their efforts led to changes in the law allowing for birth control and sex education in the years to come. In 1921, the clinic became the American Birth Control League, which changed its name to the Planned Parenthood Federation of America in 1942.

What does this have to do with Mount Sinai? Margaret Sanger and her younger sister, Ethel Byrne, were nurses. Mrs. Byrne graduated from The Mount Sinai Training School for Nurses in 1909. The sisters did not always get along, but they were united in the believe of women having the right to plan their families. Mrs. Byrne protested her sentence and her jail term of 30 days and launched a hunger strike, which brought a great deal of attention to their cause. The hunger strike lasted for five days, and then she was forcibly fed by prison doctors. Mrs. Sanger and women civic leaders, including Anne Van Kirk, the Superintendent of The Mount Sinai Hospital Training School, appealed for her release. The Governor granted the request on February 1st when Sanger promised that her sister would never break the Comstock law again. Byrne was taken to her sister’s house for care, but this episode damaged their relationship. Byrne did not actively participate in the birth control movement after this.

Ethel Byrne’s later years were quiet. She moved to Massachusetts and returned to nursing. She died in 1955. In 1962, Alan F. Guttmacher, MD left his post as Chairman of OB-GYN at The Mount Sinai Medical Center to become the President of Planned Parenthood. The Mount Sinai connection continued.

Oct 7, 2016

(Click to expand the image)

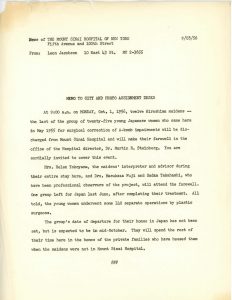

Sixty years ago this month, The Mount Sinai Hospital said goodbye to the last of a group of 25 women from Hiroshima, Japan who had spent over a year at the Hospital having surgeries to repair injuries they suffered in the nuclear blasts that ended World War II. The group of young women were called the Hiroshima

Maidens, and the project that brought them from Japan to the U.S. was the brainchild of Norman Cousins, the Editor of the Saturday Review of Literature. He raised the funds needed for the project and enlisted the help of the Quaker community of the metropolitan New York region to house the Maidens when they were not in the Hospital. Three surgeons from The Mount Sinai Hospital volunteered their time (Drs. Arthur Barsky, Bernard Simon and Sidney Kahn), and the President of the Hospital, Alfred Rose, anonymously paid for the use of four hospital beds for the duration of the project.

The Hiroshima Maidens project was a milestone in postwar American-Japanese relations. Before leaving Japan, the girls were told by some that the American doctors were going to experiment on them. As it became clear that this was not the case, the donated funds were stretched to allow Japanese doctors to come to Mount Sinai and receive training in plastic and reconstructive surgery, thus helping to strengthen the field in Japan.

The Hiroshima Maidens project continued to have life. In 1995, one of the Maidens returned to Mount Sinai to meet with Dr. Simon. At that time she gave the Mount Sinai Archives a scrapbook of photocopies of images from Hiroshima after the blast. The next year there was a conference at Mount Sinai that celebrated the project from 40 years before, and highlighted Mount Sinai’s current international efforts. In spring 2005, for the 50th anniversary of the project, the last remaining Maiden and a group of Japanese press visited Mount Sinai once again. The group came to the Archives and looked at the photos from the 1950s and read again the newspaper accounts of the Maidens’ courageous journey to New York.

On this 60th anniversary, it is unknown if any Maidens are still alive. Still, it is comforting to know that the memory – and documentation – of the project lives on, and will not be forgotten.

Sep 28, 2016

The creation of the Mount Sinai Health System in 2013, formed by the merger of the Mount Sinai Medical Center with Continuum Health Partners, brought some of New York City’s major hospitals together under a single organizational umbrella. The individual hospitals making up the Health System, however, often themselves incorporate multiple hospitals with which they have merged and affiliated over the years. As the Archives continues to collect, process and make available the records of the former Beth Israel Medical Center, we have acquired material relating to various smaller hospitals associated with Beth Israel. The records of these institutions provide a glimpse into the wide variety of small hospitals that existed in New York during the twentieth century.

Doctors Hospital

Doctors Hospital was an exclusive voluntary hospital, founded in 1929 by members of New York City’s social elite, which catered to the needs of wealthy private patients. Its Upper East Side location on East End Avenue overlooked Carl Schurz Park and Gracie Mansion (pictured, at center). In 1987 it became part of the Beth Israel Medical Center and was briefly known as Beth Israel Hospital North before being renamed Beth Israel Medical Center Singer Division. It closed in 2004, and its building was torn down the following year; the site is now occupied by luxury residences. The minutes of the Doctors Hospital Board of Directors, recently discovered in offsite storage associated with Beth Israel, are now a part of the collection of the Mount Sinai Archives.

Jewish Maternity Hospital

The Jewish Maternity Hospital was founded in 1906. Located at 270 Broadway, it provided maternity care to the Lower East Side’s growing community of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. At the urging of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies, which hoped to consolidate its medical activities during the lean years of the Great Depression, it merged in 1930 with Beth Israel, which had recently moved to a state of the art modern hospital on Stuyvesant Square. For some time the two institutions maintained separate wards within the hospital building, but by the 1940s the Maternity Hospital had been absorbed into the obstetrics department at Beth Israel. Three volumes of its patient registers, dated 1921-1933, are housed in the Mount Sinai Archives.

New York Lying-In Hospital / Manhattan General Hospital

The New York Lying-In Hospital already had a long institutional history, dating back to the yellow fever epidemic of 1798, when it moved in 1902 to a newly built home at 307 2nd Avenue on the northwest corner of Stuyvesant Square. The hospital’s time at this location was a productive one, during which members of the hospital staff pioneered the use of pharmaceutical pain management to ease the pain of childbirth. In 1932 the New York Lying-In Hospital left the site to become the OB-GYN department of the New York Hospital at its campus on the Upper East Side. The building on Stuyvesant Square became home to the proprietary Manhattan General Hospital. In 1965 the building was purchased by Beth Israel and became the Morris J. Bernstein Institute, a pioneering inpatient facility for addiction treatment. The building was sold in 1984 and is now an apartment complex, but its origin as a maternity hospital can still be seen in the elegant sculptures of infants displayed on its facade. The records of the Lying-In Hospital itself are in the Archives of the Weill Cornell Medical College, but the Mount Sinai Archives has a small assortment of records related to the Bernstein Institute during the period that it occupied the former Lying-In Hospital building.

Jul 21, 2016

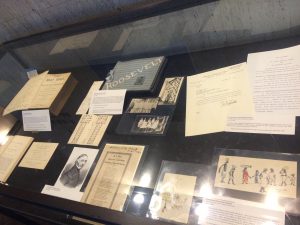

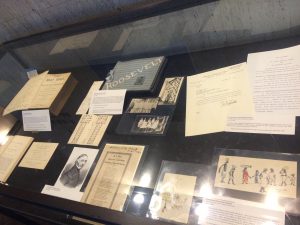

The Mount Sinai Archives has received a large amount of new archival material over the last year, well over 186 feet of paper, photographs, and (sometimes) disintegrating leather-bound volumes. The bulk of these new collections contain material from Mount Sinai St. Luke’s Hospital and Mount Sinai West (the former Roosevelt Hospital), but they also include items documenting the Beth Israel Medical Center, Mount Sinai Queens, The Mount Sinai Hospital and the Medical School. Organizing, preserving and making available such a great quantity of material is a complex and time-consuming task, but the effort is well worth it, because these collections include many important historic treasures. Those treasures are the theme for a new Archives’ display in the Annenberg Building lobby. Here are some highlights from the display.

What makes a historical document or artifact a ‘treasure’? Sometimes, historical records provide information on an important person or an institution. The 1854 Bible belonging to the Rev. Dr. William Muhlenberg, founder of St. Luke’s Hospital, is an example of that, as are the newsletters and Annual Reports of the various Mount Sinai Health System hospitals that we have received. Other times, an item can be a ‘treasure’ because it provides context for what life was like at a specific period of time, highlighting how things have changed, or perhaps showing how some things never change. The Fathers’ Book from the Woman’s Hospital in the early 1940s does that, as do the reports created by the Mount Sinai Environmental Sciences Laboratory that are displayed. And sometimes what makes an item a ‘treasure’ is just that there is something appealing, unique or unexpected about it. Who would think that the Mount Sinai Archives has a World War II era U.S. War Department issued Japanese phrase book, currently on display in the Nursing case below the Stern Auditorium stairs? It is part of the papers sent to us by the daughter of Esther Winkler Shapiro, Class of 1944.

Perhaps the most surprising treasure we found as we put this exhibit together were the photographs and documents tucked into the back of a scrapbook from the Roosevelt Hospital School of Nursing, which was formed in 1896 and closed in 1974. This scrapbook, wrapped in the traditional blue stripe of the Roosevelt uniform, was created by Evelyn I.V. Howard, Class of 1908. The last few pages of the book include photographs and notes from Nina Gage, RN, a classmate of Miss Howard’s. These pieces document Gage’s years at a Red Cross hospital at the Hunan-Yale School for Nurses in Changsha, China from 1908-1915. There are photos of the facility as well as students and faculty members.

A view of one of the display cases showing Rev. Muhlenberg’s Bible in the far left corner and the Roosevelt nursing scrapbook in the middle.

If you are nearby, please stop in and take a look at our display. If you would like additional information, please contact us at msarchives@mssm.edu.

Jun 15, 2016

The Mount Sinai Archives has recently received the records that document the histories of the St. Luke’s Hospital, The Roosevelt Hospital, and the Woman’s Hospital in the State of New York, which merged with St. Luke’s in 1953. We are still in the process of ingesting these records and figuring out what we have, but one particular series has popped up that we couldn’t wait to highlight.

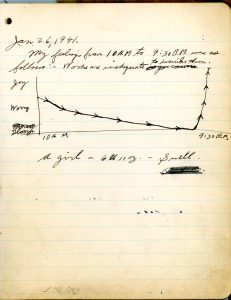

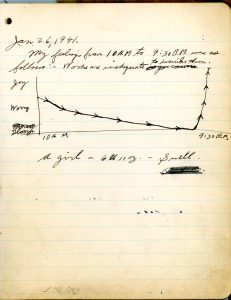

In the 1940’s, the Woman’s Hospital placed a small notebook in the waiting room on the maternity ward and asked prospective fathers to write their thoughts about their experience while there. The Archives has only four volumes, covering 1940-1944. It is unknown how long this practice continued. Still, the volumes that exist are wonderful to read, both for how the fathers (mostly) expressed their feelings as time passed and they waited with only occasional updates, as well as for how these volumes bear witness to the era in which they were created. There is a fervent entry about hoping this child will never have to know about Hitler or Nazis. There is another written by a grandmother because the father was a soldier. And there is the most obvious fact that marks them as from an earlier era: these fathers were all banished to a far away room and were not allowed to be part of the birth experience.

Below is just one page from the 1940/41 volume. It sums up the experience in the most simple of ways.

A page from the Fathers’ Book from the woman’s Hospital in 1940/41

May 24, 2016

The cemetery at Base Hospital No.3 for Americans who died at the hospital, 1918

Memorial Day is set aside to remember the servicemen and women who have died while in service to their country. Ceremonies started after the Civil War and it became a national holiday after World War II. Since injury and death are a part of war, doctors and nurses have always been witnesses to the ravages of battlefields. The image above shows the American cemetery at Base Hospital No. 3, the Mount Sinai Hospital-staffed unit that served in France.

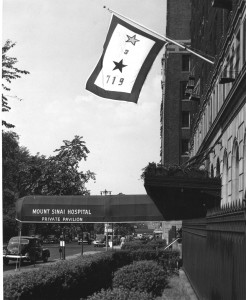

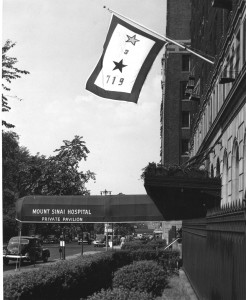

While the deaths happened abroad, the biggest impact was felt at home. It was not only families that marked their losses, but institutions as well. By World War II, service flags were a familiar patriotic symbol. The photo below shows Mount Sinai’s flag hanging from 1184 Fifth Avenue. The number on the bottom shows how many Mount Sinai doctors, nurses, staff and trustees were in the service at that time. The gold star at the top showed how many had died. By the end of the war, Mount Sinai’s numbers had grown to 802 served, nine dead.

The Mount Sinai Hospital service flag, 1944

Those nine are recognized here:

- Nils Carson

- Sydney C. Feinberg, MD

- Andrew Goldstein

- Jerome W. Greenbaum, MD

- Eugene M. Holleb, MD

- Goodell G. Klevan, MD

- Bernard Ritter, MD

- Helen Rogers, RN

- Stanley J. Snitow, MD

May 13, 2016

As the Mount Sinai Archives continues processing and cataloging the records of the Beth Israel Medical Center (today’s Mount Sinai Beth Israel), we continue to discover interesting images and ephemera from Beth Israel’s history.

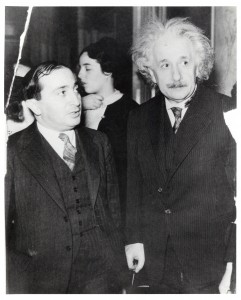

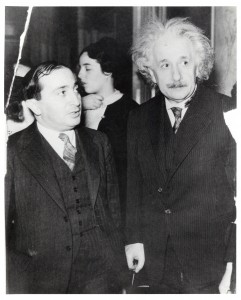

The photograph above shows Albert Einstein with Adolph Held (1885-1969), editor of the Jewish Daily Forward and brother of Dr. Isidor W. Held, a longtime member of the Beth Israel Hospital medical staff who served as President of the Medical Board from 1936 to 1938. (Update June 2017: When we first discovered this photograph in the collection, it had been incorrectly identified as a photograph of Dr. Held rather than his brother Adolph. Thanks to the family member who contacted the Archives with a correction.)

Dr. Held, a gastroenterologist, was involved in Jewish refugee aid in the aftermath of World War I, and during the rise of Nazism he became active in the movement to help medical and scientific emigres escape from Nazi Germany and its conquered territories, raising funds and publishing articles on behalf of persecuted Jewish physicians. These activities brought him into contact with Albert Einstein, who was himself a refugee from Nazi persecution and a vocal activist on behalf of other potential emigres.

This photograph is the only item in the Beth Israel collection that documents the relationship between Einstein and Dr. Held, but the Einstein Archives Online, a comprehensive directory of Einstein’s manuscripts, includes numerous entries for letters to and from Held and his wife Fanny. In 2006, a 1938 letter from Einstein to Held discussing the situation in Germany was sold at auction; the catalog listing includes a translation of the letter, which discusses their unsuccessful attempts to help an internist named Rudolph Ehrmann escape the “German gangsters.” (The following year, they were successful in obtaining passage to New York City for Dr. Ehrmann, who opened a private practice and became one of Einstein’s personal physicians.)

Dr. Held passed away in 1947. In addition to his legacy as an administrator, clinician and teacher of house staff, and the lives he saved as a refugee advocate, his posthumous impact at Beth Israel included an important annual lecture series endowed in his memory, which lasted until at least the late 1980s and brought numerous prominent physicians to BI’s downtown campus.

May 2, 2016

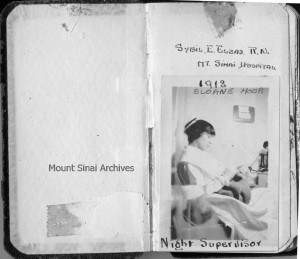

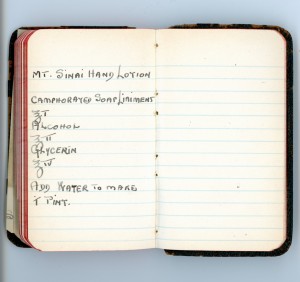

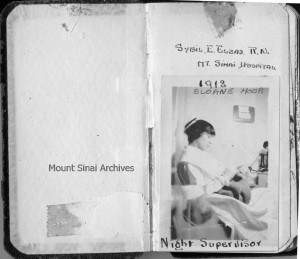

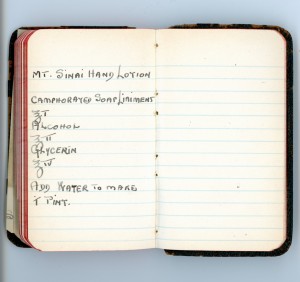

In honor of National Nurses Week, the Mount Sinai Archives would like to recognize that for over 100 years, Mount Sinai nurses have been doing it all, and then some. When she was a student at The Mount Sinai Training School for Nurses, Class of 1917, Sybil E. Elzas created a little notebook containing important things she needed to know on her clinical rotations, and then once out on her own as a graduate nurse. (Most professional nurses at this time still did private duty nursing, not hospital work.) The notebook was sized just right to slip into the pocket of her uniform’s apron. After pages and pages of definitions of terms and lists of operating room tray set-ups and dressings, towards the back of the book is a lone page noting the recipe for “Mount Sinai Hand Lotion.” Why purchase something nurses could so easily make, and at reduced cost?!

Nurses, still making a difference at Mount Sinai, 100 years later.

Inside cover of the clinic notebook belonging to Sybil E. Elzas. She is shown here as a student while on rotation to Sloane Hospital. The recipe for the lotion is at the end of the volume.

Apr 22, 2016

The Mount Sinai Archives has installed its latest quarterly exhibit in the lobby of the Annenberg Building. This season’s exhibit, “Hospital Trustees and the Making of New York City,” looks at the role of some of the trustees of the Mount Sinai Health System hospitals, accomplished figures who left their mark not only on their respective hospitals but on New York City as a whole.

One exhibit case contains photographs and memorabilia documenting the life and career of Charles H. Silver, who served for nearly five decades as President of the Board of Trustees at the Beth Israel Medical Center, the predecessor of today’s Mount Sinai Beth Israel. (Some of the highlights of the Mount Sinai Archives’ Silver collection have previously been featured on the blog.) The child of impoverished Lower East Side immigrants who worked his way up to wealth and influence, Silver was active in politics and philanthropy, chaired the New York City Board of Education, and was a pioneer of interfaith relations in a multicultural global city.

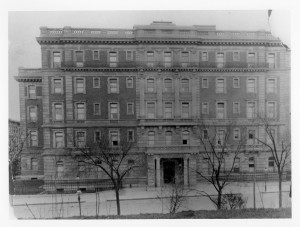

Pictured: The original Mount Sinai Private Pavilion, built in 1904 with an endowment from the Guggenheim family.

The second exhibit case documents the legacy of the Guggenheim family at Mount Sinai. The role of the Guggenheims in New York City philanthropy is perhaps best known in connection with the Guggenheim Museum, but members of the family also played an important role at Mount Sinai, where they served as Trustees, donors, and vocal supporters from 1889 until the end of the 20th century. Since 1904, their name has been on Mount Sinai’s largest patient care building, a symbol of their dedication to the city and people of New York.

This quarter’s Nursing History exhibit, located underneath the stairs to Stern Auditorium, documents the participation of Mount Sinai School of Nursing graduates in the Spanish-American War and the Spanish Civil War, the latter of which marks its 80th anniversary this year.

Apr 15, 2016

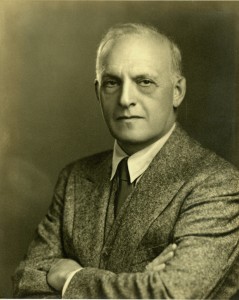

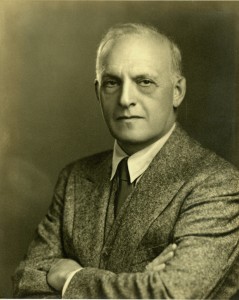

Dr. S. S. Goldwater, Director of The Mount Sinai Hospital from 1903-1928

Every month is a celebration of something, and April is National Poetry Month. In keeping with the season, the Mount Sinai Archives would like to offer up a poem. This was written by S. S. Goldwater, MD (1873-1942). He served as the Director (COO) of The Mount Sinai Hospital from 1903-1928 and also served as the New York City Commissioner of Health and the Commissioner of Hospitals. He was known as one of the foremost consultants on hospital architecture in his era, and helped create the field of modern hospital administration. He loved to write poetry and often exchanged poems with his friends. He wrote the poem below for the celebration of The Mount Sinai Hospital’s 90th anniversary in 1942, just a few months before he died. It was reprinted in a memorial booklet after his death:

In closing, let me address these lines to your distinguished President, to your faithful and energetic Director, and to those members of the Board and Staff with whom it was my privilege to be associated for a time in the development of this great institution:

Full many a year has passed since you and I

Began to think in unison, and talk

Of what a hospital is and what it should be.

Well, thoughts like ours do not die a-borning

But, seized by eager wills, emerge as deeds,

By which new shapes are formed, reshaped again,

Until the world about us is part Nature’s,

Part our own.

Although we’ve not achieved

The perfect institution of our dreams—

Of love, and art, and science all compact—

Rejoice we may, for we have lived to see

The hospital we cherish yield to change

From small to great, from careless to exact,

From home of sorry pestilence to proud

And comely scene of perfect cleanliness

Equipped with all that science knows to aid

Physician, nurse, and sick, to whom in honor

We pledge again our faithful, firm support.