Jun 9, 2022

In years past, as the weather warmed up, the staff and alumni looked forward to renewing old acquaintances and socializing with colleagues from across the hospital’s departments. This blog post will highlight the three main traditions of spring, mention their roots and how they evolved.

The first event was the annual alumni dinner, which gathered all the graduates of the Resident training program together to enjoy a good meal, good conversation, and informative lectures. The Society of the Alumni of St. Luke’s Hospital of New York City was established in 1891 and was formed with the intent to “foster collegiality and scientific discourse and to honor accomplished colleagues at an annual dinner.”

The image above, taken from the News of St. Luke’s newsletter, depicts the dinner held on April 30, 1965, at the New York Hilton Hotel.

This photo memorializes the St. Luke’s 1973 alumni dinner at the 7th Regiment Armory.

In 1896, Roosevelt Hospital ‘ex-interns’ met at the hospital to plan the twenty-fifth anniversary of its opening and organize The Roosevelt Hospital Alumni Association. Its stated purpose was “…maintaining loyalty to the institution and promoting its broader usefulness.” Unfortunately, the Archives does not have any photos documenting their celebrations over the years.

Every June during the 1960s, St. Luke’s Attendings invited the Residents to join them for a “Field Day.” Held at New Jersey’s Englewood Country Club, the usual barriers of position, age, and authority were ignored during an afternoon of hotly contested athletic events (softball, golf, and tennis, swimming, etc.), followed by a casual dinner and evening entertainment.

Evening offerings were often films created by actor/director wannabes, Drs. Harry Roselle and Theodore Robbins and the various colleagues they could round up to help. One year’s offering was a Dr- Kildare-meets-Dracula-at-St.-Luke’s horror flick titled, “Anemia of Uncertain Origin.” Another was a spy thriller á la a 1960s TV comedy favorite titled ‘Get Smart,’ called “Aardvark,” in which Secret Agent 95.6, battled Aardvark, a Fu Manchu-type enemy who developed an infamous blood sludging device.

Each year’s outing was documented with a panoramic photograph of attendees. These photos, usually between four and six feet long and about ten inches high, have proven to be a challenge to store in the Archives. About ten of them arrived, each individually tightly rolled. They required re-humidifying in a makeshift humidification tank in order to relax the paper enough to allow them to be flattened for storage. They are available for viewing for those who wish to walk down memory lane.

In case you, dear reader, are curious, the Field Day photo was cut in two in order to be printed in the former newsletter, The News of St. Luke’s. The images used here were scanned from the newsletter because the originals are too large to fit on current in-house scanners. It may also be of interest to note that the dinner photographs, whose originals are two to three feet long and eight to ten inches high, were taken with a fish-eye camera, which has curved lenses to allow the whole room to fit into one image. The author is not sure what equipment was used to capture the huge Field Day images.

Unfortunately, one year in the early 1970s the event was cancelled due to unforeseen circumstances, and it was not picked up again in the following years.

The final big spring event for many years was the St. Luke’s Hospital School of Nursing graduation ceremonies held at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, just south of the Hospital. Nursing students would line up at the Hospital and proceed down Amsterdam Avenue, marching up the front steps to enter the Cathedral and take seats at the front while their families observed the ceremonies from behind them. At the end of the ceremonies the graduating class would pose for a group photo on the Cathedral steps.

The above images, taken from the News of St. Luke’s newsletter, are of the graduating class of 1955; the image below shows the graduating class of 1974, the year the St. Luke’s Hospital School of Nursing program closed its doors and merged with the Columbia University School of Nursing Bachelor of Science program.

Roosevelt Hospital also had a School of Nursing, founded in 1896. At first, students were accepted on a rolling admission any time, and as students successfully completed the required coursework, diplomas, graduate caps and pins were awarded with little fanfare in the Administration Building. By the 1920s a formal cycle of classes developed, and graduation was set at a fixed time of year. At first, ceremonies were held in the Syms Operating Room, and later, as the number of students grew, the ceremony was moved to a hotel ballroom. Unfortunately, the Archives does not have images from the Roosevelt Hospital School of Nursing graduations, and like St. Luke’s, the hospital-based school also closed its doors in 1974, but the Alumni Association is still fairly active and enthusiastic about staying connected.

Michala Biondi for the Aufses Archives.

May 16, 2022

A history of the ambulance service at Roosevelt Hospital, today’s Mount Sinai West, is available here. See the Building Beth Israel series for more information about the history of Mount Sinai Beth Israel. An interactive map of Beth Israel historical locations is available here.

National EMS Week is May 15-21. In this blog post, we’re celebrating by looking back at a brief history of emergency medical services at Mount Sinai Beth Israel.

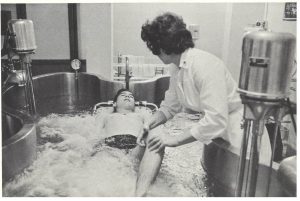

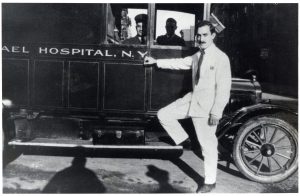

The first ambulance service began at Beth Israel Hospital in 1906. It first used a horse-drawn carriage, later switching to automobiles in 1915. During this early period, ambulances were manned by members of the house staff, including Nettie Shapiro, MD, the first female house staff at MSBI in 1909.

By 1984, Beth Israel was “the first voluntary hospital in New York City to have attending physicians fully trained in emergency service on duty around the clock, every day of the week.” New York City did not mandate such 24-hour care in EMS participant hospitals until June 1, 1987.

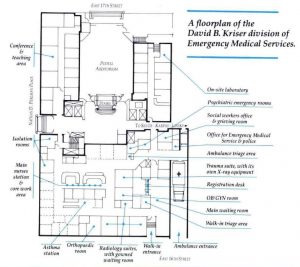

In 1990, the Division of Emergency Medical Services was named for David B. Kriser, a Beth Israel trustee, in honor of a $3 million bequest from him. This led to a major renovation, and the division doubled in size.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser with research credit to Nicholas Webb

Apr 7, 2022

Woman’s Hospital (1855-1952) is a unique institution in the history of American medicine, in several ways. It has claimed to be the first hospital in the world devoted exclusively to “the problems of medicine peculiar to women.” Founded by a group of well-to-do women in NYC, in conjunction with Dr. J. Marion Sims, this group formed the Women’s Hospital Association, and ran the Hospital themselves for the first several years. It was re-organized and re-chartered as the Woman’s Hospital in the State of New York in 1857, making the drastic change of introducing an all-male Board of Governors, who ran the top-level business of the organization. Considering the limits of female power in 1857 and connections in business and finance needed at that time in order to run a growing medical facility, it makes some sense. (1)

Women did, however, continue to run the majority of the daily business of the Hospital. In the 1880s several of the ‘Lady Managers’ were invited to join the Board of Governors by necessity, to fill several slots that had gone unfilled for a prolonged time. It was a successful experiment and made permanent after about a year, re-creating the Board almost equally by gender. What is a bit odd, considering the strong presence of women in the leadership, is that it took until 1918 for a woman to break into the medical end of the work. However, the woman who did it was as unique and unusual as the Hospital for which she worked.

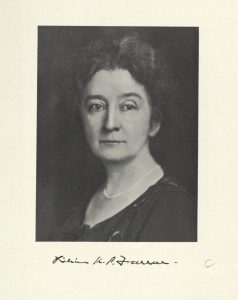

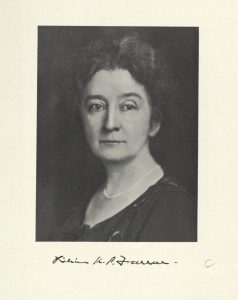

Lillian Keturah Pond Farrar was born in Newton Center, Massachusetts in December 1871 to Jefferson Clinton Farrar Jr., and Sarah D. Pond. (2) She earned her BA at Boston University, and completed her medical education at the Cornell University Medical College. Records there indicate that prior to enrolling she took medical classes at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children between 1896 and 1899. She graduated from Cornell in 1900 at age 29, and returned to the New York Infirmary to take her internship. (3) After that, she spent several years (1901-1904) training in Paris and in Vienna, visiting medical clinics in Paris, Berlin, London, Stockholm, and Rome as well, much like any male physician of that time might do. (4)

Lillian Keturah Pond Farrar was born in Newton Center, Massachusetts in December 1871 to Jefferson Clinton Farrar Jr., and Sarah D. Pond. (2) She earned her BA at Boston University, and completed her medical education at the Cornell University Medical College. Records there indicate that prior to enrolling she took medical classes at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children between 1896 and 1899. She graduated from Cornell in 1900 at age 29, and returned to the New York Infirmary to take her internship. (3) After that, she spent several years (1901-1904) training in Paris and in Vienna, visiting medical clinics in Paris, Berlin, London, Stockholm, and Rome as well, much like any male physician of that time might do. (4)

After her European training was completed, our information about Dr. Farrar jumps to 1918. That year Lilian K.P. Farrar, MD, age 47, became a Junior Attending Surgeon, the first woman physician appointed at Woman’s Hospital. She became an Attending Surgeon in 1927 and Consulting Surgeon in 1935 at age 64. (5)

Relatively unknown today, Dr. Farrar was active in the broader medical community during her working life. She was a woman of firsts: the first woman to serve as an Assistant Professor in Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Cornell University Medical College from 1918 until 1953 (ages 47- 82) and the first woman physician appointed Chief of Clinics (gynecology) there as well. She was the first woman elected as a Fellow of the American Gynecological Society in 1921, and the only woman in the Society for fifty years, as another woman wasn’t welcomed in until 1971 (6). She was the first woman to serve as a Governor of the American College of Surgeons, serving multiple terms between 1925 and 1937. Additionally, she was the first – and only – woman to be a ‘founding Diplomate’ of the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (1930). Her body of articles, published between 1917 and 1937, indicate that she was an accomplished gynecological surgeon, even collaborating with a colleague on perfecting irradiation techniques for treating gynecological cancers. (7)

Outside of professional accomplishments, Farrar, who remained single throughout her life, numbered among the social elite of her time. She is listed in both the New York Social Blue Book for 1930 (8), and the Register of the National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York 1893-1926. (9) The Society requires members be direct descendants of someone, or in her case, ten of them, who “lived in the American colony and rendered it service before July 5, 1776.” (10) Farrar supported the Woman’s Suffrage movement and fostered the acceptance of women as interns at Bellevue Hospital, New York, in 1914 and at Woman’s Hospital in 1920. (11)

Another gap in our information about Dr. Farrar exists between 1953 and her death in the Lake Placid Memorial Hospital on June 22, 1962, attributed to arteriosclerotic heart disease (12), at the age of 90. (13) She is buried in Newton Center, Massachusetts.

Sources:

1. Annual Reports of Woman’s Hospital, 1855; 1857; 1918; 1920

2. Family Search website listing: https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/MQQX-JLV/lillian-keturah-pond-farrar-1871-1962

3. Cornell University Medical College Students Register 1898-1907. NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine Medical Center Archives.

4. Dr. Lillian K.P. Farrar. Medical Woman’s Journal (vol. XLIII, page 190, July 1936).

5. Obituary. The Times Newsletter of Woman’s Hospital, Dec 1962, Vol 14, #2 p.11

6. “Gender Ideology in the Rise of Obstetrics.” Naoko ONO. The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 17 (2006)

7. Women in Medicine website: http://obgynhistory.net/miscwomandocs.html

8. NY Social Blue Book: http://bklyn-genealogy-info.stevemorse.org/Directory/Blue/1930.BlueF.html

9. Register of the National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York, 1893-1926 https://www.google.com/books/edition/Register_of_the_National_Society_of_Colo/TdBKAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=the+Register+of+the+National+Society+of+Colonial+Dames+in+the+State+of+New+York.+1893-1926&pg=PA3&printsec=frontcover

10. The National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York website membership inquiries page: https://www.nscdny.org/membership-inquires

11. Dr. Lillian K.P. Farrar. Medical Woman’s Journal (vol. XLIII, page 190, July 1936).

12. Unidentified clipping, from the Elizabeth Bass Collection on Women in Medicine, Rudolph Matas Medical Library, Tulane University Medical Center, LA. https://library.tulane.edu/sites/default/files/media-files/matas/matas_collections_bassindex2014_01.pdf

13. Obituary. The Times Newsletter of Woman’s Hospital, Dec 1962, Vol 14, #2 p.11

Authored by Michala Biondi, Associate Archivist

Mar 16, 2022

An interactive map of Beth Israel historical locations is available here. See the Building Beth Israel series for more information about the history of MSBI.

Mount Sinai Brooklyn is one of the more recent New York hospitals to join the Mount Sinai Health System. Prior to its most recent incarnation, the hospital dates to the 1950s and was a long-time division of Mount Sinai Beth Israel.

Prior to the 1950s, the location was a series of interlocking lots. In 1953, the parcel was created at 3201 Kings Highway for Samuel Berson, MD, a specialist in allergy and immunology, to create a nursing home there. Though the exact timing is unknown, the nursing home was converted into Kings Highway Hospital shortly after with 212 beds. In 1980, King’s Highway Hospital opened its North wing, without an increase in the number of beds. As a small, private, community hospital, not much documentation has survived from those years.

On July 11, 1994, a special meeting of the Beth Israel Medical Center Board of Trustees passed a resolution “that the Medical Center proceed to negotiate the acquisition of Kings Highway Hospital.” By adding Kings Highway to the existing Petrie and North divisions, “on the basis of total admissions per year, the acquisition makes Beth Israel the largest voluntary hospital in New York City and one of the largest in the United States.”

The period following Beth Israel’s acquisition marked a time of rapid renovation and development at the Kings Highway Division. This included renovations at the Surgi-Center (1996); the introduction of three-bed inpatient Acute Dialysis Unit (November 1996); an expansion of the Russian Health Service and other Russian language amenities (1998); and an expansion of the emergency room from six to seventeen treatment slots (Summer 1998). Perhaps most significant was the groundbreaking for the new building starting in May 1998, which included underground parking, a new emergency department, ICU, and five new operating rooms. The new facility, called the Acute Care Pavilion, was built on what was previously the hospital parking lot, and opened in May 2000.

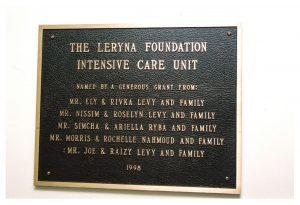

These renovations and expansions continued with significant investment from donors. In February 1997, Beth Israel Kings Highway Division in Brooklyn received a $150,000 gift from the Leryna Foundation, the family foundation of Ely Levy, an electronics distributor and leader of the Sephardic community in Brooklyn. The gift doubled the number of beds in the ICU from six to twelve. In 1997, the Greater Montreal Convention and Tourism Bureau named Kings Highway Hospital as the beneficiary of proceeds for its production of Robert Lepage’s The Seven Streams of the River Ota at the Next Wave Festival of the Brooklyn Academy of Music. And finally, in December 2002, the Louis Mintz Family Waiting Room in Critical Care Unit was endowed.

With Beth Israel’s merger into the Mount Sinai Health System, the Kings Highway Division was renamed Mount Sinai Beth Israel Brooklyn in January 2014, and then was shortened to Mount Sinai Brooklyn in May 2015. It remains part of the Mount Sinai Health System today.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser with research credit to Nicholas Webb

Mar 2, 2022

Title page of the 1864 Annual Report of the Directors of Jews’ Hospital in New York

Mount Sinai Hospital’s predecessor institution, Jews’ Hospital in New York, was established in 1852, opened in 1855, and initially admitted only people of the Jewish faith and accident victims. A mere twelve years later in 1864 the Board of Directors decided to open the hospital to all, regardless of faith. Then in 1866, to reflect this new policy, the institution changed its name to Mount Sinai Hospital. But why did the Hospital become non-sectarian? At a point in time when many Hospitals founded by other creeds continued their religious affiliations, Jews’ Hospital broke with tradition. It might come as a surprise that the decision to treat people regardless of faith was influenced by the Civil War and the New York City Draft Riots of 1863, one of the “bloodiest race riots in American history.” The profound devastation wrought upon Black people during the gruesome riots shaped New York as we know it today and had a profound impact on the early days of our health system.

In the introduction to The First Hundred Years of The Mount Sinai Hospital of New York, 1852-1952, the authors posit that Jews’ Hospital, as it was in the geographic center of the riots, was “the asylum for their dead and injured. An eventual result for the Hospital was its adoption of the nonsectarianism which has been its policy ever since.” Which begs the question: who did they treat, and did treating victims of the riots actually persuade the Hospital’s Leadership to change its policy? To answer that question, we need to know what occurred in New York City during the years leading up to the 1864 decision. The United States was in the thick of the Civil War which raged from 1861 to 1865. New York City, while positioned as a northern city allied with the Union, was in fact quite a conservative city due to its financial connections to the south.

Section 1869 map of New York showing the Jews’ Hospital in blue rectangle (map courtesy of Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library)

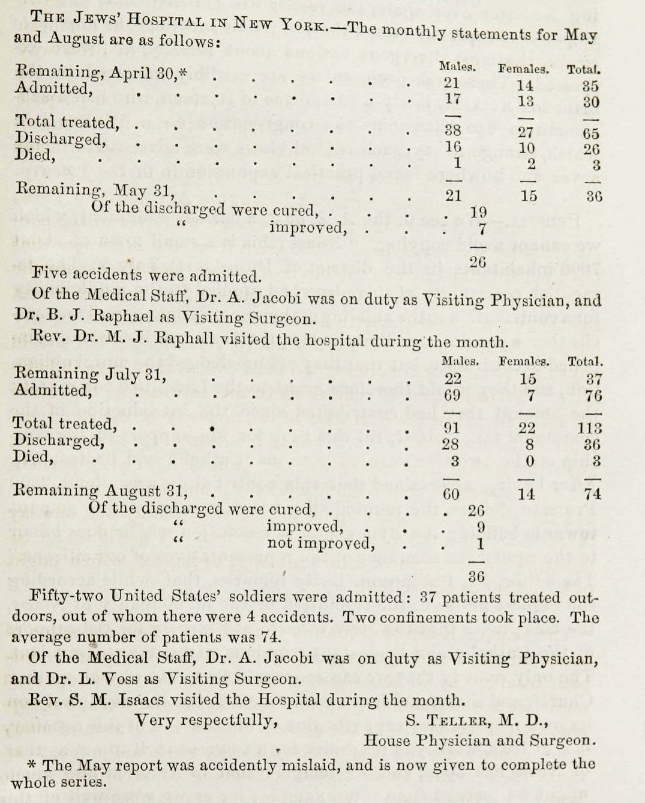

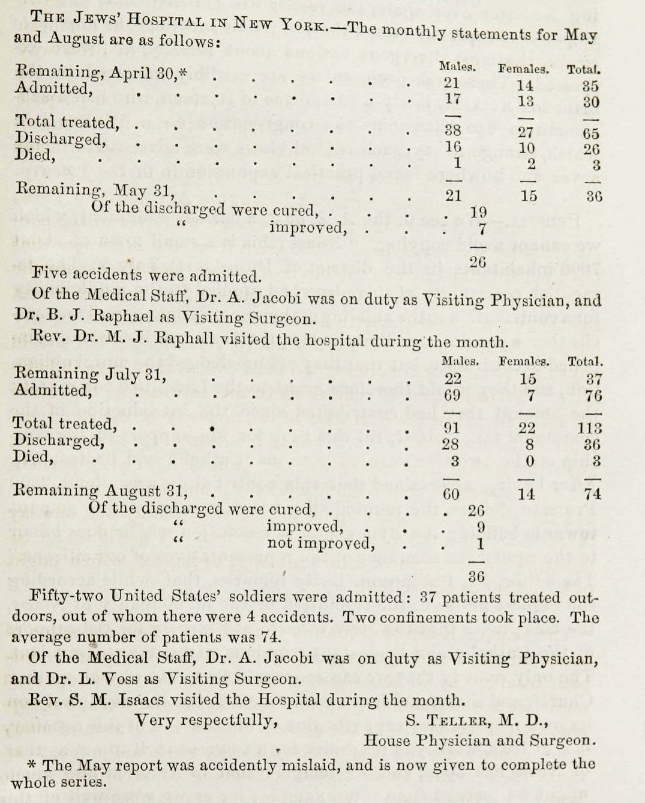

During the Civil War the Jews’ Hospital in New York was located on the south side of 28th Street between 6th and 7th Avenues and admitted on average 30 patients a month. In 1864 the staff consisted of three consulting surgeons, three attending surgeons, four attending physicians, “one resident physician and house surgeon, one superintendent, three nurses, three domestics, and one cook.” Annual reports state that from 1855 to 1860 the Hospital treated 1,285 people. However, during the war years, we are unable to say how many in total were admitted because we do not have annual reports for the years 1861, 1862, and 1863. However, Dr. Teller, House Physician and Surgeon, gave monthly reports on all but a few occasions to The Occident and American Jewish Advocate:

Dr. Teller either did not report the 1863 June and July statistics or the newspaper did not include them. But August, the month after the draft riots, the number of patients treated, 113, is higher than usual.

The Hospital underwent a great transformation during the Civil War. One of its three Attending Surgeons, Dr. Israel Moses, left to serve in the Union Army. Joseph Seligman, who had been on the Hospital’s Board since 1855 resigned his position in 1862 because of his “increasing responsibilities” frequently attending advisory meetings with President Lincoln. The most dramatic change was in 1861 when the Board of Directors resolved to establish a ward for injured Union soldiers, first totaling 48, then 69 beds.

The federal draft law was put into place in the summer of 1863, but it provided an exemption for people who could pay $300 or find someone to take their place. This infuriated the working class, the Irish and other recent immigrants, especially in New York, where Union loyalty was not a given. After the names had been drawn for the first round and published in the weekend’s papers, many New Yorkers were enraged. A large mob formed on the next day, and proceeded to attack and burn down the Provost Marshal’s building, where the draft was taking place. From there the mob moved all around the city, rioting, burning down entire buildings, injuring innocent bystanders, looting and committing outright murder. Described as “bitter street-to-street warfare”, the city was in chaos for four days.

Black people were the primary target of the mob’s atrocious violence due to racism and scapegoating, newspapers having created the narrative that enslaved people, once free, would take jobs from recent immigrants. Mobs lynched eleven Black men, hanging their mutilated bodies from lampposts. The total death count is unknown, but estimates range from over 100 to several hundred. The repercussions of the four days of extreme violence shape New York City even today. Because of the riots, it is estimated that nearly a thousand Black New Yorkers fled Manhattan en masse, seeking permanent refuge elsewhere, leaving behind their homes and communities. In their exodus from what was a racially integrated city, they settled in safer places, such as the historic Black community of Weeksville in Brooklyn (which was a city in its own right at the time). In the aftermath, New York became a more segregated city.

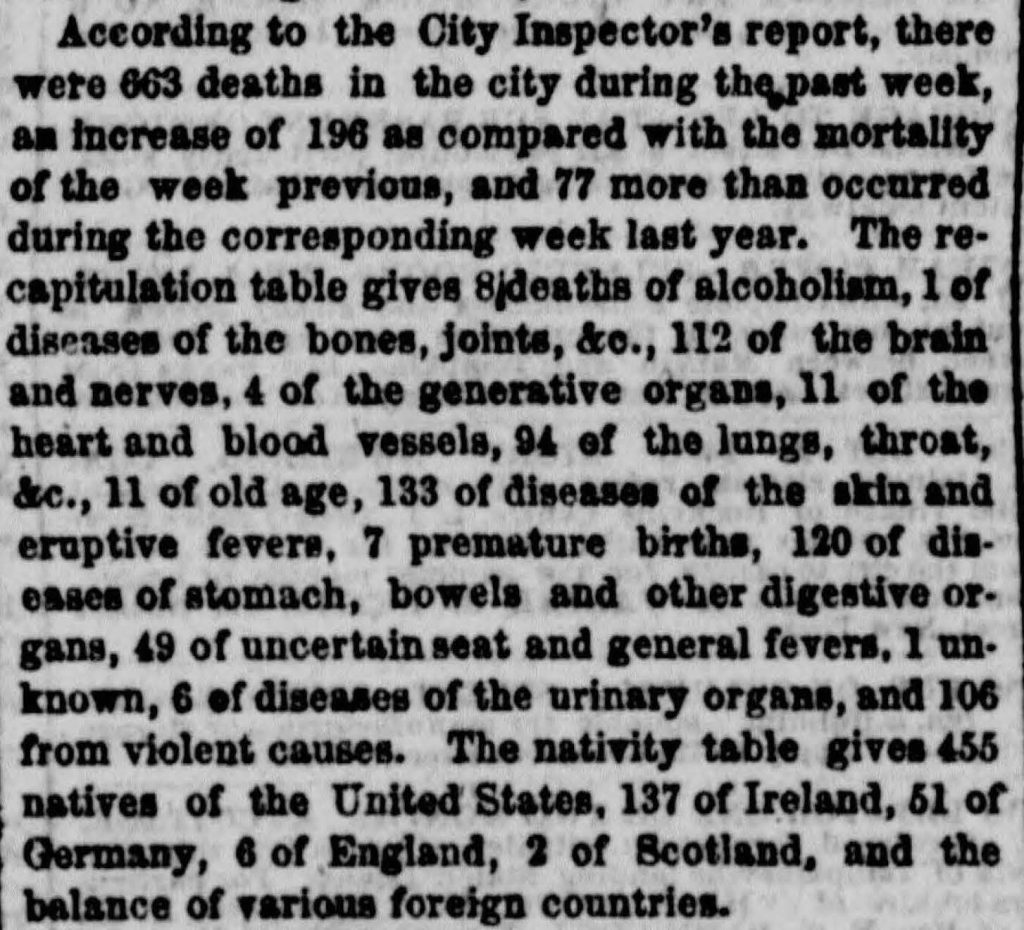

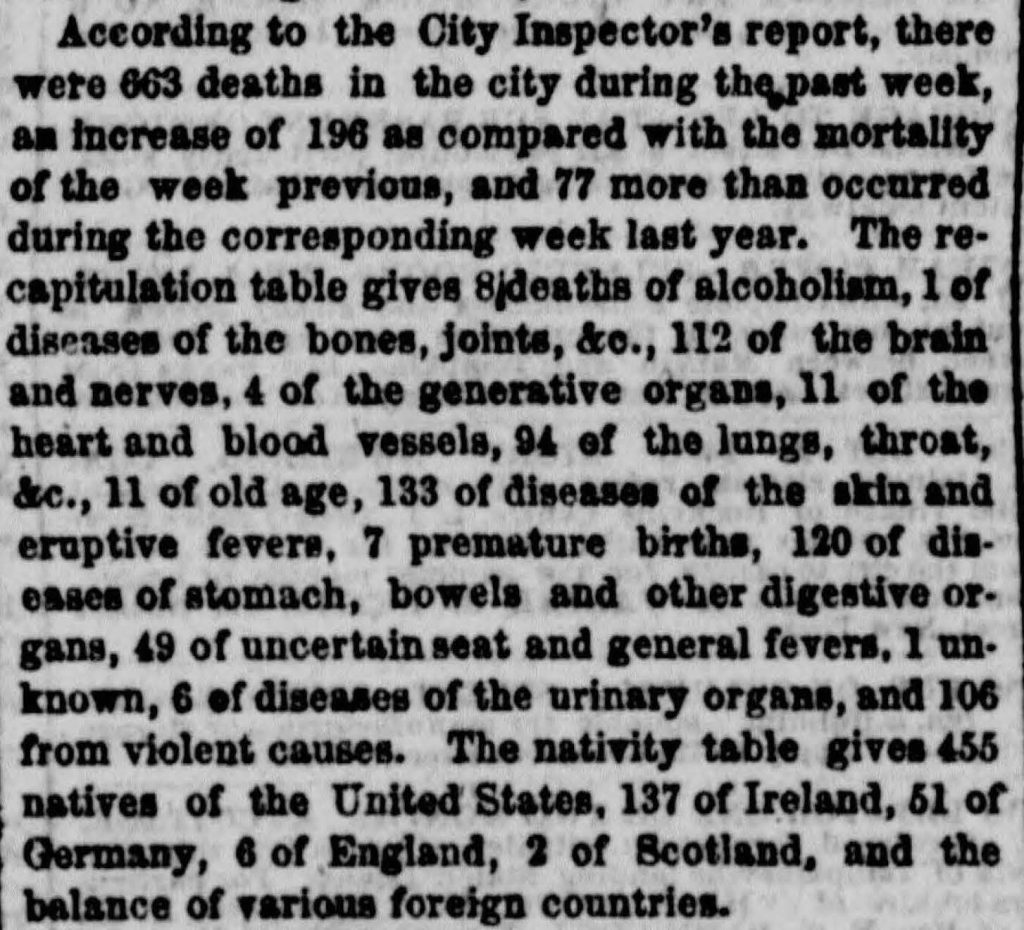

Excerpt from the July 21, 1863 edition of The New York Herald showing 106 deaths from violent causes, presumably the Draft Riots.

One early Mount Sinai doctor recalled:

In the early [1860’s] the hospital must have had its share of the casualties from the draft riots which occurred in the neighborhood, and of which I was in part an eyewitness: the burning of the colored Orphan Asylum in 40th Street, the attack on the Provost Marshall’s office on Broadway and 28th Street, the hanging of a [Black man] to a lamp post at 6th Avenue and 33rd Street, and the escape of frightened colored men, women, and children from the mob to the State Arsenal at 35th Street and Seventh Avenue under protection of a squad of soldiers.

Do we know how many people were treated at the Jews’ Hospital? While the Archives does not possess the case books from that era, we know that, “the geography of the rioting was such that Jews’ Hospital was frequently the center of its fury, and during the bloody days that ensued, it became the sanctuary of the sick and the wounded.” The newspapers of the time described multiple extremely violent events that took place only a few blocks from the Hospital. In all likelihood, the Hospital treated dozens of riot victims and the staff would witness the particular terror and brutal violence inflicted upon Black people.

In reading the minutes’ book entries of the subsequent months, there seems to be no end to the mundane issues the Board of Directors addressed. Rarely is there an explanation of motive or greater historical context included with a decision recorded in such matter of fact reports. However, in the months following the riots, the Hospital’s Board of Directors were:

Sensitive to their obligations to the country and the community during this period, the Board of Directors was also preparing the ground for the nonsectarian policy which has distinguished the Hospital ever since. Accident patients of all nationalities, races and religions had been accepted since the first day of the Hospital’s existence. But the national crisis crystallized the Board’s determination to rise above sectarianism and abolish it completely. In 1864, the Executive Committee had reported, “The Committee deem it proper to observe that many of those admitted to the Hospital were not of our faith, no distinction ever being made as to either the nationality or the religious belief of the sufferer.”

References

Albon P. Man. “Labor Competition and the New York Draft Riots of 1863.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 36, no. 4, 1951, pp. 375–405. https://doi.org/10.2307/2715371.

Hirsch, Joseph and Doherty, Beka. The First Hundred Years of the Mount Sinai Hospital of New York, 1852-1952. Random House: New York, 1952.

Jews’ Hospital in New York. Annual Report of the Directors of the Jews’ Hospital in New York, 1860. https://archive.org/details/annualreportofdi1860jews/page/18/mode/2up

Meyer, Alfred. “Recollections of Old Mount Sinai Days.” Journal of the Mount Sinai Hospital, vol. 3, no. 6, 1937, pp. 295-307.

Authored by J.E. Molly Seegers

Jan 31, 2022

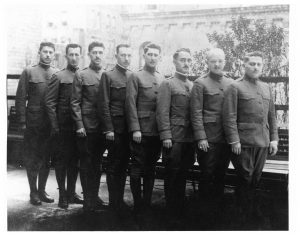

Since the 2013 merger of the Continuum Health Partners into the Mount Sinai Health System, medical students working in the System’s hospitals have earned their MDs from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Newer staff and students may be unaware that prior to 2013, the Continuum Health Partners, made up of St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital, Beth Israel Medical Center and the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, now all a part of Mount Sinai’s System, played host to medical students attached to a different medical school. In fact, from very early days, Roosevelt Hospital and her sister institution, St. Luke’s Hospital, were associated with Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons (P&S), though Roosevelt’s ties are closer. How did this come to be exactly?

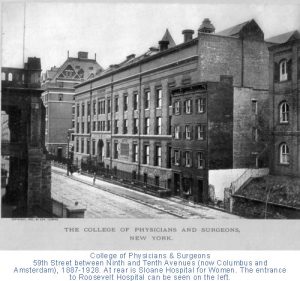

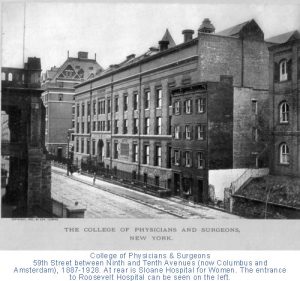

In 1885, P&S was located on East 23rd Street and Fourth Avenue, now known as Park Avenue South. William H. Vanderbilt, an American businessman and philanthropist, died in December of that year. He left a legacy of $300K and a plot of land on West 59th Street between Ninth and Tenth Avenues to P&S for the express purpose of building a new medical school, the largest donation to a medical school up to that time.

The College of Physicians and Surgeons on West 59th Street across from Roosevelt Hospital. You can see the Hospital’s Administrative Building port-cohere front column to the left in the image. (Photo source: Archives & Special Collections, Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

It just so happened that the Roosevelt Hospital, which had opened its doors several years earlier, was across the street from the new building. Of the twelve physicians chosen to be the first clinical staff of the Hospital, almost all of them were P&S alumni and held teaching positions there. It probably was no surprise to the staff to see medical students from P&S coming over to observe their professors’ clinics and surgeries.

By 1914, P&S students received bedside teaching on patient wards; by 1936, fourth-year students were allowed into the operating rooms. In 1928, the College of Physicians and Surgeons moved to the newly constructed medical center campus at 168 Street in Washington Heights, but their students continued to travel to clinical training at Roosevelt, and a number of other hospitals in the area.

Surprisingly, in over sixty years of P&S student training at Roosevelt Hospital, there was only a ‘handshake’ agreement between the medical school and the Hospital. However, by the late 1940s, there was discussion on the subject, and on October 24, 1951, the Board of Trustees put into place a formal affiliation with Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, allowing the students of the medical school to work at the hospital as part of their formal training. The agreement was signed by all parties on May 12, 1952. In 1971 it was renewed and expanded.

Medical studies aren’t the only tie between Columbia and Roosevelt Hospital, however. In 1964, an affiliation agreement between Columbia University’s School of Dental and Oral Surgery and Roosevelt Hospital was signed allowing dental students in to the surgery. That same year a two-year program in anesthesiology for the registered nurses was established at Roosevelt to help end the shortage of practitioners in this area. This program moved to Columbia University’s School of Nursing after the Roosevelt Hospital’s School of Nursing closed, and the loose ends of Roosevelt’s program merged with Columbia’s. The CRNA program – Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists – continues there to this day.

With the 2013 merger of St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center into the Mount Sinai Health System, ties to Columbia University’s programs may have come undone, but the history and influence of each institution upon the other remains, in the drive to produce outstanding medical professionals.

Jan 10, 2022

In a previous blog post, we looked at Beth Israel Hospital’s role in the 1918 Influenza Epidemic. Since then, we’ve done further research into the World War I correspondence in the Beth Israel records, as well as the Beth Israel Board of Directors and Committee minutes, which both provided rich details to supplement this history.

In early March 1918, influenza had reached New York. By March 25, 1918, an unknown correspondent (likely Louis J. Frank, Beth Israel Hospital superintendent) wrote that there was “quite an epidemic in the City of Grippe,” referring to New York City as literally the “City of the Flu”. As World War I continued on, many Beth Israel workers had joined the war effort, and their correspondence with the hospital describes the epidemic on the front lines. The first wave of the flu was relatively mild, and on May 13, 1918, Dr. Alfred A. Schwartz of the American Expeditionary Force, reported as much from France:

“I have been appointed Otolaryngologist to the contagious disease wards at the camp hospital and altho [sic] the title sounds like work, there must first be complications to the infectious diseases, and secondly…there must be some patients to have the diseases, and fortunately there is little to do.”

As the second, more deadly wave swept the world, the topic of influenza became more pressing in the correspondence, and was increasingly addressed in the Board minutes. In the November 17, 1918, minutes, the Board noted that back on the home front in New York, Beth Israel attended to “50 to 60 cases of Influenza a day during the height of the epidemic and…our records of cures was high, and our record of deaths was very low.” This is a significant deviation from the previous blog post, which stated that only twenty-nine patients total were treated during the epidemic at Beth Israel. Sources conflict on this point.

Staffing was amongst the most pressing issues at this time – with much of the medical staff overseas, Louis J. Frank, himself recovering from the flu, commented in a letter from October 23, 1918: “Our whole force is gone. If you were to come back today, you wouldn’t find a familiar face…From a house staff of 15 we have been reduced to a staff of five, and of the five, three have been laid up on account of influenza.” He goes on to describe the issue of hiring enough nurses, which was making him “frantic.” Superintendent Frank was a proponent of the conscription of women, “especially those women who have the vote,” to counteract staffing shortages in nursing in the war and at home.

The Board of Directors’ minutes reflect similar staffing concerns. The minutes for November 17, 1918, stated: “During the epidemic the Surgical Staff consisted of one man, the others became infected with the disease. On the Medical side we only had two men, the others also sick.” This appears to have resulted in redeployment of other clinical workers, and the Board resolved on “the discontinuance of the work of the Polio Department on account of the epidemic of Influenza and Pneumonia to release the doctors and nurses connected with the clinic for the more important work.” The minutes also noted that the “pupil nurses” from Beth Israel Training School for Nurses (today’s Phillips School of Nursing at MSBI) “after their day’s work was over, did extra work in the district on these cases, spending an hour or two on emergency cases requiring special care.”

The close of 1918 marked a turning point. With the War over, and a dwindling number of cases following the peak of the second wave, the end was in sight. In a letter from November 27, 1918, Superintendent Frank wrote:

“Things are getting into shape at the Hospital. We were considerably upset on account of the War, shortage of help, doctors, nurses, the Influenza epidemic, and the general anxiety, but with victory came a relaxation and we are now awaiting the homecoming of you men who have done so much to achieve this victory.”

The Board also noted, grimly, on November 17, 1918, that Beth Israel was “the only Hospital [in New York City] that didn’t lose a nurse, a doctor, or an employee by death.” On January 19, 1919, the Board moved to give House Staff and pupil nurses bonuses for their contributions and made especial note of the nurses’ service: “pupil nurses…after their trying [work and school] day of 12 and many times 14 hours, went out in the tenement houses and did extra work for several hours. Of course, this work was not for patients of the Hospital, but it was nevertheless our work, for they were the poor sick of our neighborhood.”

On November 23, 1919, the Board made note of the U.S. Public Health Service’s prediction that the influenza epidemic would return. Fortunately, this never came to pass. By 1920, the virus mutated to cause only ordinary cases of the seasonal flu, and the epidemic was effectively over.

Sources:

More resources on Mount Sinai Health System Hospitals and World War I are available here.

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Dec 13, 2021

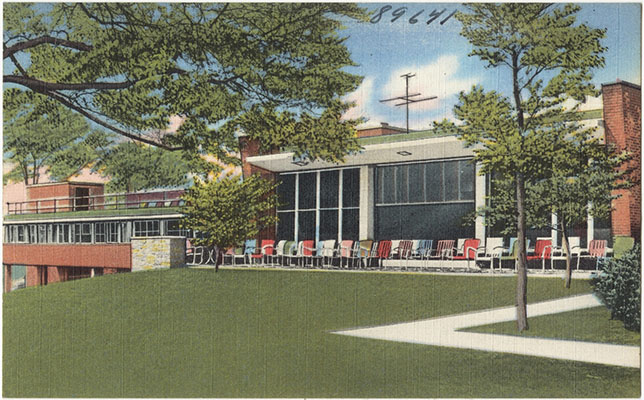

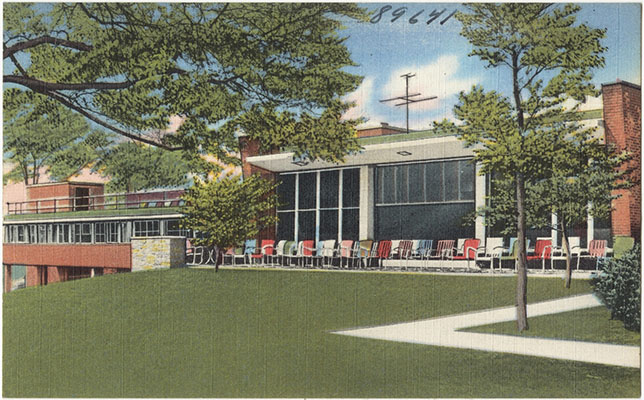

On December 10, 1927, the St. Luke’s Hospital celebrated a long-standing goal, the dedication of the St. Luke’s Convalescent Home in Greenwich, Connecticut. The newly constructed buildings were attractive, comfortable and able to provide space for eighty-five patients, and included space for administrative offices, the culinary department, nurse’s quarters, and laboratory and operating facilities. The hospital began admitting patients on December 20. All of this was thanks to the 1925 gift of 200 acres of property called Byram Woods by Mrs. Hicks Arnold. The Board of Managers called it “the great event of the past year.” The land came with an additional gift from Mrs. Arnold of $1 million of which $500K was earmarked for the construction of the convalescent hospital, and $500K as an endowment.

Since 1919, St. Luke’s had been looking for just such a donation to relieve the Hospital of the many patients that were recuperating or rehabilitating at the Hospital, taking up beds needed for more acute care cases. In fact, from the early years of the Hospital, the Managers frequently sought convalescent space for those patients who no longer needed acute care, but still needed to recuperate or rehabilitate under medical and, at times, surgical supervision. If possible, the ideal spot would be within a twenty-five mile radius of the city, in a rural area where patients, especially children, could benefit from space, sunshine, and fresh air. Most of the early locations, on Long Island and in New Jersey, were second homes, loaned to St. Luke’s for a period of time, or were independent convalescent hospitals that took in St. Luke’s patients. For a while, St. Luke’s had an exclusive relationship for convalescent care with St. Johnland Hospital, in King’s Park, Long Island, but only for about 30 children. Over time, the Board of Managers realized they need a larger and more permanent facility. Indeed, soon after the new building was opened, plans for its expansion began, so great was the demand.

Since 1919, St. Luke’s had been looking for just such a donation to relieve the Hospital of the many patients that were recuperating or rehabilitating at the Hospital, taking up beds needed for more acute care cases. In fact, from the early years of the Hospital, the Managers frequently sought convalescent space for those patients who no longer needed acute care, but still needed to recuperate or rehabilitate under medical and, at times, surgical supervision. If possible, the ideal spot would be within a twenty-five mile radius of the city, in a rural area where patients, especially children, could benefit from space, sunshine, and fresh air. Most of the early locations, on Long Island and in New Jersey, were second homes, loaned to St. Luke’s for a period of time, or were independent convalescent hospitals that took in St. Luke’s patients. For a while, St. Luke’s had an exclusive relationship for convalescent care with St. Johnland Hospital, in King’s Park, Long Island, but only for about 30 children. Over time, the Board of Managers realized they need a larger and more permanent facility. Indeed, soon after the new building was opened, plans for its expansion began, so great was the demand.

In 1930, an additional gift from Mrs. Arnold provided the funding for the construction of a separate children’s wing. Dedicated as the Arnold Children’s Pavilion, it had a capacity of forty-seven children, increasing the Hospital census to one hundred thirty four, (and increasing the degree of quiet for the adult patients, a Board member noted with a smile). It also protected each population from communicating outbreaks of contagious illness to the other, such as flu or diphtheria, etc. The Arnold Children’s Pavilion opened in May of 1932.

Here is a bird’s eye view of the campus. The Hicks Arnold Pavilion is to the far right.

The staff tried to keep daily life similar to regular home life. For the children, that meant school. A teacher-recreational director helped to keep the young ones current with their appropriate public school grade, as well as providing all manner of health-building activities. The hospital had a large schoolroom and playroom with a gymnasium and plenty of out-door space for walks and games if children were able.

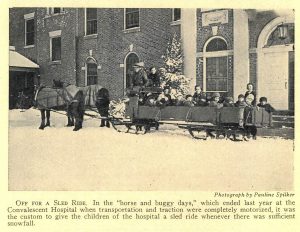

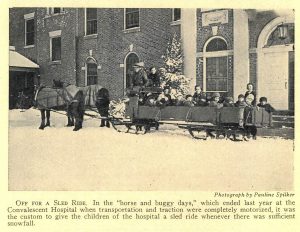

In the winter, a large sled pulled by horses provided rides in the fresh air, with lots of warm blankets for patients to snuggle under. A large sunporch provided a space where less mobile patients could enjoy the outdoors from inside while playing cards, board games, pool, billiards, ping-pong, or bingo, etc. In the warmer weather outdoor games such as croquet, golf and quoits were available.

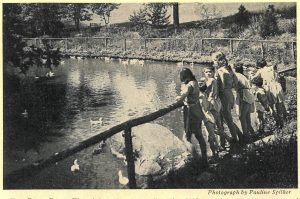

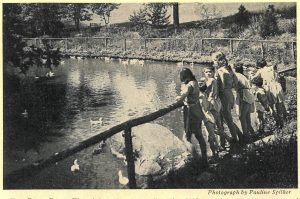

A duck pond entertained both children and adults. The chapel offered daily morning prayer and weekly worship services for the faithful. Patients could also volunteer to do light chores in the building or on the premises if they were of a mind to do so. In the early 1940s a Hospitality Shoppe was opened in the hospital, giving patients a place to go ‘out’ and have a cup of coffee or a soda with friends and buy small items that might be needed during a long stay.

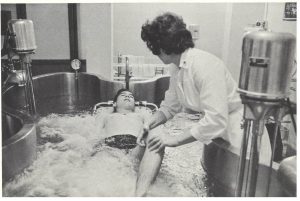

Lest this makes the Hospital sound like a vacation spot, it is necessary to note that a complete medical staff was available to supervise the progress of each patient and a fully outfitted rehabilitation section was available for those needing physical rehab. In addition to the  Attending and Consulting staff of physicians and a Resident physician living on-site, other specialists included physical therapists, social workers, occupational therapists, dietitians, nurses, recreation leaders, laboratory technologist, and pediatrics specialists.

Attending and Consulting staff of physicians and a Resident physician living on-site, other specialists included physical therapists, social workers, occupational therapists, dietitians, nurses, recreation leaders, laboratory technologist, and pediatrics specialists.

Over time, improvements in medical technology, changes in Hospital leadership, finances, and hospital goals, as well as lifestyle changes of the city population, led to the decision to relocate convalescent hospital functions back onto the city campus. In 1964, the Byram Woods campus closed and the property sold and used for other purposes.

Nov 23, 2021

For more information about former Beth Israel locations, see the Building Beth Israel series. An interactive map of Beth Israel historical locations is available here. See all our holdings related to the Jewish Maternity Hospital, Doctors Hospital, and the Singer Division.

Mount Sinai Beth Israel has affiliated with several hospitals over its 130-year history. Though their names may have disappeared over time, their impact on the hospital’s history remains. This blog post looks at two Beth Israel affiliates, Jewish Maternity Hospital and Doctors Hospital, and their lasting influence on Beth Israel.

Jewish Maternity Hospital

The Jewish Maternity Hospital (JMH) first opened in February 1909 at 270 East Broadway with two consulting physicians, twelve house staff, and fifteen obstetrical nurses. By 1927, JMH accumulated a large building fund and wanted to expand its premises. The Jewish Federation of Philanthropies, which helped to fund many of the local Jewish hospitals during this period, preferred that it become part of a larger hospital rather than be maintained as a separate institution.

As another hospital funded by the Federation, not to mention a close neighbor on the Lower East Side, Beth Israel was a natural candidate – however, the proposed merger was not without controversy. At a 1928 meeting of the Board of Trustees, Beth Israel Superintendent Louis J. Frank firmly rejected it as an unwarranted drain on the space and resources and recommended that a separate building on the Beth Israel campus be constructed so that JMH did not take over beds in the newly built Dazian Pavillion. He also suggested that JMH consider affiliating with The Mount Sinai Hospital instead. (Prior to the Federation’s merger proposal, JMH had planned to construct a new building on 108th Street.) Board President Cohen, however, noted that control of the Maternity Hospital’s $700,000 building fund would enable Beth Israel to solve the financial difficulties caused by cost overruns for the construction of Dazian.

Later that year, a compromise was reached. The Federation proposed that Beth Israel absorb the JMH, that the boards of the two institutions merge (with a subcommittee for the newly formed maternity department consisting of the former JMH trustees), and that Beth Israel allocate beds in the new building specifically for obstetrical purposes. A motion was approved to accept the proposal, albeit reluctantly, with the Board noting that it “did not invite the merger, nor does it feel that there is any need or emergency, as far as Beth Israel Hospital is concerned… since provision has already been made in the new building for an adequate, efficient and up to date Maternity Service.”

The merger was announced in 1929 and finally occurred in 1930. Plans to construct a new building for the hospital adjacent to the Beth Israel campus in Stuyvesant Square were announced in 1931, though this building was never completed. Over the next decade, obstetrical services slowly transitioned to the Beth Israel campus, and in 1946, the JMH name disappeared. In 1948, the Obstetrics service notes, “the long-awaited physical consolidation of all labor and delivery rooms is effected.”

Doctors Hospital

Construction for Doctors Hospital began in 1929, amid a debate in the larger medical world about the necessity of private rooms versus the larger, shared wards common to the nineteenth century. When it opened in 1930, Doctors Hospital was described as “homelike,” “a model hospital with the atmosphere of a modern hotel” with “soft tinted walls, guest rooms and a private icebox…for every patient.” With its unusually well-equipped private rooms, and its location at 70 East End Avenue overlooking Carl Schurz Park and Gracie Mansion, Doctors Hospital secured its reputation as being a luxe medical facility for the famous and well-to-do for the rest of the century.

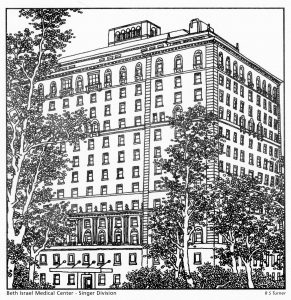

On August 3, 1987, it was announced that Doctors Hospital had been acquired by Beth Israel Medical Center and was renamed Beth Israel North. The name changed again in 1998 to the Beth Israel Medical Center Singer Division. In these years, the Hospital had a few notable developments. In 1988, it acquired a device for treating gallstones and bile duct stones, called a biliary lithotripter. It was the first in New York City, and Charles McSherry, MD, spearheaded the project. In 1990, the New York State Department of Health approved a certificate of need for the construction of twenty-four chronic dialysis stations at the hospital due to a lack of such facilities in Manhattan.

However, the Singer Division did not last. By 2004, it was formally closed, and the property was sold to developers. The facility was torn down the following year and was replaced with apartments.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser with research credit to Nicholas Webb

Nov 10, 2021

The Neustadter Home was created by a provision in the 1905 will of Caroline Neustadter to serve as a convalescent center for women patients after leaving the hospital. It opened in July 1919 on the northeast corner of Central Park Avenue and McLean Avenue in Yonkers, on land once owned by Boss Tweed, leader of Tammany Hall. In 1936, an agreement was reached between The Mount Sinai Hospital and the Neustadter Home whereby Mount Sinai could send patients to the facility. Three years later, men began to be admitted as well.

The original Neustadter Home in the 1950s

The Moses Weinman wing, opened in 1949

As hospitals saw the increasing value in freeing up beds for more acute cases by discharging patients to rehabilitation hospitals, Neustadter needed to expand. The Moses Weinman wing was added in 1949, bringing the institution up to 69 beds from the previous 56. The facility also enhanced its medical care services. To reflect this evolution, the name was changed from the Neustadter Home to the Neustadter Convalescent Center in 1954. Over the years, the patient population was composed primarily of post-surgical cases. As the 1971 Mount Sinai Annual Report on convalescent care said: “So often before we have described the true function of Neustadter as a bridge that spans illness to complete recovery.” In 1969, Mount Sinai was given preferential use of the Center and eventually the Neustadter Board members and the medical staff were affiliated with Mount Sinai.

The Convalescent Center did not have a bright future, however. In a 1959 study of Neustadter, only 24% of patients could afford the full weekly charge of $84. Money was a perennial problem. Also, because the Home was twelve miles from Mount Sinai Hospital, it was hard to provide follow-up care by physicians. In 1972, the Neustadter Board dissolved and transferred their assets to The Mount Sinai Hospital. The next year, Mount Sinai sought to sell the Convalescent Center. The sale for $1 million to a local Hebrew high school was announced in 1973, but the school struggled to make the payments. The matter sputtered along for a few years, and in 1980 the property was finally sold to a realty company. In 1983, a shopping center opened on the site, including a large Waldbaum’s grocery store. The shops remain; the Waldbaum’s is gone. The Neustadter Convalescent Center has also totally disappeared.

For information on what archival material the Aufses Archives has relating to the Neustadter Convalescent Center, click here.

Lillian Keturah Pond Farrar was born in Newton Center, Massachusetts in December 1871 to Jefferson Clinton Farrar Jr., and Sarah D. Pond. (2) She earned her BA at Boston University, and completed her medical education at the Cornell University Medical College. Records there indicate that prior to enrolling she took medical classes at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children between 1896 and 1899. She graduated from Cornell in 1900 at age 29, and returned to the New York Infirmary to take her internship. (3) After that, she spent several years (1901-1904) training in Paris and in Vienna, visiting medical clinics in Paris, Berlin, London, Stockholm, and Rome as well, much like any male physician of that time might do. (4)

Lillian Keturah Pond Farrar was born in Newton Center, Massachusetts in December 1871 to Jefferson Clinton Farrar Jr., and Sarah D. Pond. (2) She earned her BA at Boston University, and completed her medical education at the Cornell University Medical College. Records there indicate that prior to enrolling she took medical classes at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children between 1896 and 1899. She graduated from Cornell in 1900 at age 29, and returned to the New York Infirmary to take her internship. (3) After that, she spent several years (1901-1904) training in Paris and in Vienna, visiting medical clinics in Paris, Berlin, London, Stockholm, and Rome as well, much like any male physician of that time might do. (4)

Since 1919, St. Luke’s had been looking for just such a donation to relieve the Hospital of the many patients that were recuperating or rehabilitating at the Hospital, taking up beds needed for more acute care cases. In fact, from the early years of the Hospital, the Managers frequently sought convalescent space for those patients who no longer needed acute care, but still needed to recuperate or rehabilitate under medical and, at times, surgical supervision. If possible, the ideal spot would be within a twenty-five mile radius of the city, in a rural area where patients, especially children, could benefit from space, sunshine, and fresh air. Most of the early locations, on Long Island and in New Jersey, were second homes, loaned to St. Luke’s for a period of time, or were independent convalescent hospitals that took in St. Luke’s patients. For a while, St. Luke’s had an exclusive relationship for convalescent care with St. Johnland Hospital, in King’s Park, Long Island, but only for about 30 children. Over time, the Board of Managers realized they need a larger and more permanent facility. Indeed, soon after the new building was opened, plans for its expansion began, so great was the demand.

Since 1919, St. Luke’s had been looking for just such a donation to relieve the Hospital of the many patients that were recuperating or rehabilitating at the Hospital, taking up beds needed for more acute care cases. In fact, from the early years of the Hospital, the Managers frequently sought convalescent space for those patients who no longer needed acute care, but still needed to recuperate or rehabilitate under medical and, at times, surgical supervision. If possible, the ideal spot would be within a twenty-five mile radius of the city, in a rural area where patients, especially children, could benefit from space, sunshine, and fresh air. Most of the early locations, on Long Island and in New Jersey, were second homes, loaned to St. Luke’s for a period of time, or were independent convalescent hospitals that took in St. Luke’s patients. For a while, St. Luke’s had an exclusive relationship for convalescent care with St. Johnland Hospital, in King’s Park, Long Island, but only for about 30 children. Over time, the Board of Managers realized they need a larger and more permanent facility. Indeed, soon after the new building was opened, plans for its expansion began, so great was the demand.

Attending and Consulting staff of physicians and a Resident physician living on-site, other specialists included physical therapists, social workers, occupational therapists, dietitians, nurses, recreation leaders, laboratory technologist, and pediatrics specialists.

Attending and Consulting staff of physicians and a Resident physician living on-site, other specialists included physical therapists, social workers, occupational therapists, dietitians, nurses, recreation leaders, laboratory technologist, and pediatrics specialists.