Jan 29, 2021

On St. Luke’s Day, October 18, 1846, the Rev William A. Muhlenberg announced to his congregation the of the Church of the Holy Communion that he believed they should established a church-related hospital in New York City to help support the poor in the community. He proposed that half of that morning’s collection be the first donation towards the goal of building such a hospital. Muhlenberg described the future hospital as a “Hotel Dieu,” – God’s Hotel, ‘a large hotel full of sick guests,’ or a “Christian family entertaining their guests, all of whom were sick.” After twelve years, and much fundraising, the doors to St. Luke’s Hospital opened to care for the sick poor of the City.

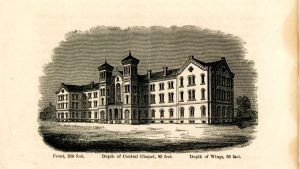

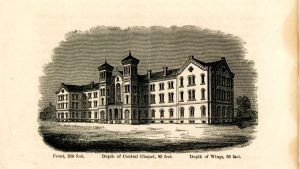

St. Luke’s Hospital’s 1858 site on W. 54th St.

Likewise, Mount Sinai Morningside’s sister hospital, Mount Sinai West, formerly Roosevelt Hospital, was also established to aid the city’s sick poor. James H. Roosevelt (1800-1863), experienced a life-altering illness that left him invalid. He decided to close his legal practice, cancel his wedding plans and devote his life to living frugally, carefully managing his fortune, to “establish … a hospital for the reception and relief of sick and diseased persons and for its permanent endowments.” Under the terms of James Henry Roosevelt’s will, the hospital was to be a voluntary hospital that cared for individuals regardless of their ability to pay. The Hospital opened in 1871 on West 59th Street between Ninth and Tenth Avenues. At its opening, Roosevelt Hospital was considered one of the most modern hospitals in the country.

Roosevelt Hospital in 1871

This year, 2021, we celebrate the 175th anniversary of the founding of St. Luke’s Hospital, now called Mount Sinai Morningside, and the 150th anniversary of the opening of Roosevelt Hospital, now called Mount Sinai West. During a time of pandemic, it may not be possible to have a big bash to celebrate the contributions, sacrifices, and simple hard work completed by the staff of these two hospitals. However, we can note the dates and celebrate in small ways, and be grateful for both hospitals that have provided dedicated health care, research, and innovations in medicine over so many years of service.

Jul 6, 2020

This started out as a story about Althea Gibson, the first African American to win at Wimbledon, which she did on July 6, 1957. It was also about a summer sport, and being outside – two things people today find important and hopeful. But, as often happens in the Archives, those stories reminded us of other stories, which are, of course, about Mount Sinai.

In 1950, Harlem-born Althea Gibson made her U.S. Open debut at a time when tennis was largely segregated. On July 6, 1957, when she claimed the women’s singles tennis title, she became the first African American to win a championship at London’s All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, aka Wimbledon. (Arthur Ashe was the first African American to win the men’s singles crown at Wimbledon in 1975. Ashe later had quadruple bypass surgery at St. Luke’s Hospital in 1979.) The Associated Press named Althea Gibson Female Athlete of the Year in 1957 and 1958. During the 1950’s, Gibson won 56 singles and doubles titles, including 11 major titles. Gibson retired from tennis and later became a professional golfer. She was voted into the National Lawn Tennis Association Hall of Fame in 1971 and died in 2003.

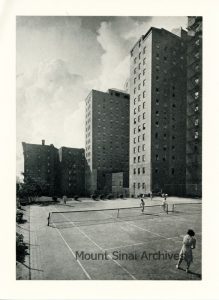

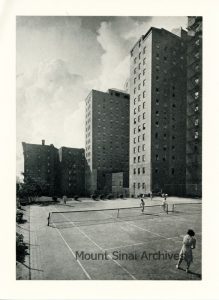

The Mount Sinai Hospital tennis courts on 5th Ave and 99th St, behind 5 E. 98th St., where KP is today.

Tennis has a long, up-and-down history at Mount Sinai. The first tennis court was built at the Hospital in the late 1800’s, back when the Hospital was still located at Lexington Avenue and 67th St. Space was tight, so the court was built between buildings, and the only way to get to it was to climb through a window on one of the wards. (Fortunately, a gong would sound whenever an Attending arrived at the Hospital, so the players were warned to get back inside.) In 1904, Mount Sinai moved uptown to 100th St., and it took 20 years before tennis returned. The growing House Staff asked the Trustees to build tennis courts that they could use for exercise. The Trustees

A small pewter trophy belonging to Noreen McGuire, School of Nursing Class of 1932. The trophy was for winning the tennis tournament in 1929.

eventually agreed in June 1923 and two courts were built on the southeast corner of 99th St and 5th Ave. Mount Sinai had purchased the land for future expansion needs, but had recently completed major additions to the campus and had no immediate plans to build. The courts were used by the Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing for gym classes, and nurses and doctors could sign up to play when a court was free.

The Aufses Archives has a wonderful interview with Gus Burton from 1988. Mr. Burton joined Mount Sinai’s staff in 1948, first as an x-ray file clerk, and then later trained as a technician in the Dept. of Radiology. What initially attracted him to work at Mount Sinai was because there was a tennis court. Here is how he described it:

Burton: …Back in those days the buses that ran along Fifth Avenue were owned by a company called the Fifth Avenue Bus Company. They had double deckers. The top deck was so that you could ride the bus for a nickel. At the time I was a student at NYU and sometimes I would take the bus down because the classes were at Washington Square. It was almost like a bus tour going down Fifth Avenue, seeing all the different places, and I saw the Hospital. I wasn’t impressed with the hospital so much, but where Klingenstein is there used to be tennis courts. At that time I was an avid tennis player, and I could see these people playing tennis. I thought it was very, very interesting, because I had found that there weren’t many places to play tennis in New York and here these people were running around playing tennis. Eventually, one day I was coming back home and I got off the bus. It was approaching the end of the semester and I said I need to find some kind of work for the summer. It was raining pretty hard, so I ran under the canopy that they had by the [Guggenheim] Pavilion. So I said, let me just check in here and see what’s going on. In those days, they didn’t really have what you call a personnel office. I guess they called it an employment office. They had about one or two clerks and the person who ran it, a Mr. Kerr (?). I just walked in and asked them if they had any jobs available. Said Mr. Kerr, “we may have some available in the radiology department. We’ll refer you to the person there who is looking for somebody and see what happens.”

So I went over and I was interviewed by a Dr. Joan Lipsay. She was the second in command in the radiology department. She was just really impressed that I came along and, sure, we’ll take you and they hired me as an X-ray file clerk. So I have always said in the years since then, that I had enough sense to come in out of the rain.

Interviewer: Did you ever get to play tennis?

Burton: Well, I found out after I started working here that those tennis courts were for the professional staff, the doctors and the nurses, and they were the ones I had seen playing on them. It so happened that one of the radiologists on our staff was an avid tennis player, he used to play out there frequently so I was able to get with him and I did get a chance to play on those tennis courts.

Unfortunately for Mr. Burton, the tennis courts were closed later in 1948, when Mount Sinai began the process of building the Klingenstein Pavilion along 5th Ave. It would be 65 years before tennis came back to Mount Sinai, but this time it was in a much different form. In 2013, it was announced that The Mount Sinai Medical Center was now the official medical services provider for the United States Tennis Association (USTA) and the U.S. Open. In addition, Alexis C. Colvin, MD, from the Leni and Peter W. May Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, would serve as the USTA’s Chief Medical Officer. In 2020, this continues to be the case. Every now and then, a mini-tennis court is built in the Guggenheim Pavilion lobby to showcase the Hospital’s role with the USTA, and for a brief moment, tennis is played again at Mount Sinai.

May 18, 2018

By some remarkable coincidence, many Mount Sinai Health System buildings have been dedicated or opened in May.

The Beth Israel Hospital opened its first facility in a rented loft in May 1890 and then moved to 196 Broadway the next year. In May of 1892 they moved again, this time to 206 E. Broadway and 195 Division St. Beth Israel remained at this location until the completion of the Jefferson & Cherry Street building in 1902. Beth Israel did not have another May opening until May 15, 1966 when the Linsky Pavilion opened.

Beth Israel’s Jefferson and Cherry Street location

The Linsky Pavilion, which opened in May 1966

On May 17, 1855, a religious service was held to inaugurate the opening of The Jews’ Hospital in the City of New York, which became The Mount Sinai Hospital in 1866. Presiding at the inauguration was Rabbi J.J. Lyons, with Rabbis Leo, Sternberger, Rubin, Cohen, Waterman, Schickler and Tebrich serving as cantors.

The original building of The Mount Sinai Hospital

The second site of the Hospital

When Mount Sinai had outgrown this site, the Trustees decided to move uptown to the block of Lexington Avenue between 66th and 67th Streets. The cornerstone for the new hospital was laid on May 25, 1870 and the completed hospital was opened on May 29, 1872.

The 1904 building along 100th Street

Within 25 years, the Hospital had again filled its site and decided to move to its current home next to Central Park, between 100th and 101st Streets. The Park ensured that the hospital would not again get surrounded by the bustle of the City’s streets. The cornerstone for this new hospital was laid on May 22, 1901. In May 1922, Mount Sinai marked the completion of a massive expansion project that extended the hospital across 100th Street down to 99th Street. This included 1184 5th Avenue, which today is the oldest building on the Mount Sinai campus.

On May 23, 1952, The Mount Sinai Hospital celebrated the dedication of the Klingenstein Pavilion on 5th Avenue.

This was built as Mount Sinai’s Maternity Pavilion, and remains the home of our OB-GYN department. At the same event, the Atran Laboratory and the Henry W. Berg, MD Laboratory buildings were both dedicated as well.

The Klingenstein Pavilion on 5th Avenue

Vice President Ford and Walter Annenberg looking at the portrait of Mrs. Annenberg at the dedication in 1974

And finally, in perhaps Mount Sinai’s biggest dedication, on May 26, 1974, the new Mount Sinai School of Medicine welcomed Vice President Gerald Ford and the Annenberg family to celebrate the formal dedication of the Annenberg Building. When this building opened, it was the thought to be the largest space in this country devoted to medical education.

St. Luke’s Hospital on 5th Avenue

The Mount Sinai Hospital was not alone in its fascination with May for buildings. On May 21, 1857, the St. Luke’s Hospital chapel opened at the Hospital’s first site and a year later (May 13, 1858) the hospital itself opened at 5th Ave between 54th and 55th Streets.

The Woman’s Hospital in the State of New York, which became the Women’s Division of St. Luke’s Hospital in 1952, also had a May dedication tradition. On May 4, 1855 the Woman’s Hospital was opened at 83 Madison Avenue. Almost 50 years later, on May 17, 1904, the cornerstone was laid at a new site at Amsterdam Avenue and 110th Street.

The first home of the Woman’s Hospital

The 1904 west side Woman’s Hospital building

Finally, on May 25, 1965 the Woman’s Hospital opened in a separate building on the St. Luke’s campus on Amsterdam Avenue and 114th Street.

Apr 17, 2017

Nurses and doctors of St. Luke’s Hospital Evacuation Hospital No. 2

April 2017 is the 100th anniversary of the entry of the United States into World War I. Like many institutions in American society, the American hospital system and its doctors and nurses were rapidly mobilized to join the war that had been raging in Europe since the summer of 1914. The Mount Sinai Archives has now installed a display in the Annenberg Building north lobby outlining the activities of the hospitals in the Mount Sinai Health System.

In New York City, The Mount Sinai Hospital, St. Luke’s Hospital and The Roosevelt Hospital (today’s Mount Sinai West) all contributed to the war effort by establishing overseas units affiliated with their respective hospitals, and many doctors at Beth Israel Hospital volunteered individually. The records, photographs and correspondence on display in these cases reflect the experience of a war that defined a generation.

For the medical officers and administrators in charge of overseas hospital units, organizing effective hospital service on a scale never before seen was an immense logistical challenge. And for the individual doctors and nurses working with patients, who saw at close hand the terrible destruction inflicted by new methods of trench warfare and aerial combat, all while dealing with a world-wide pandemic of influenza, the war was an experience of medicine at its most fundamental, as they struggled under harsh conditions to relieve human suffering.

The items on display include images of the staff from the hospitals in their World War I roles; a scrapbook from Marion Moxham, a nurse from Ireland who joined with the Mount Sinai unit, Base Hospital No. 3; letters home from physicians to the Beth Israel Hospital administration; dog tags; a medal that was awarded to members of the Mount Sinai unit; images of the wounded and wards of St. Luke’s Evacuation Hospital no. 2 and a photo of the mascot of the Roosevelt Hospital group.

Nov 30, 2016

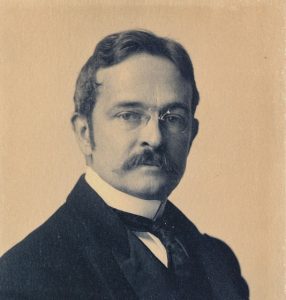

Robert Abbe (1851-1928) was a surgeon and pioneer radiologist in New York City. He was born in lower Manhattan and educated in NYC’s public schools. He attended the College of the City of New York (S.B., 1870) and Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons (M.D., 1874).

Abbe was best known as an innovative plastic surgeon, particularly for developing a procedure for repairing hair lip deformities (now commonly known as the Abbe Flap), and for  pioneering the use of radium as a treatment for various medical conditions. His many published articles document the breath of his surgical experience and the successes he had using radium to treat patients.

pioneering the use of radium as a treatment for various medical conditions. His many published articles document the breath of his surgical experience and the successes he had using radium to treat patients.

He served as a surgeon at the New York Hospital, St. Luke’s Hospital, Roosevelt Hospital, and the New York Babies Hospital, and was also a professor of surgery at the Women’s Medical College of New York, The New York Post-Graduate Medical College, and the College of Physicians and Surgeons.

In his free time, Abbe enjoyed drawing, painting oil portraits, and watercolors, and the emerging art of photography. During his later years he spent summers in Bar Harbor, Maine where he developed an interest in the Native American population of the area. He began collecting Native American tools and artifacts that he found in the area and in Stone Age relics he found on Mount Desert. He dreamt of creating a museum to display his extensive collection, and raised funds to do so. Unfortunately, he did not survive to see his dream fulfilled; the museum, which carries his name and still operates, opened a mere five months after his death of anemia at age 77, most likely due to handling radium.

A small collection of his papers and many reprints of his articles are open to researchers at the Mount Sinai Archives. The collection guide is available on the Archives web site, http://icahn.mssm.edu/about/ait/archives/collection/robert-abbe.