May 28, 2020

Mount Sinai physicians have a long tradition of making important contributions to the scientific literature. A good example is the following case from the 1910s, when typhus swept the world, killing thousands of people.

In 1910, Nathan Brill, MD, a doctor in the Department of Medicine, published a description of what he thought was the endemic form of typhus; this became known as Brill’s Disease. (Later Hans Zinsser showed that it was not endemic, but a mild recrudescent form of epidemic typhus and the name was changed to Brill-Zinsser disease.) In 1913, Harry Plotz, MD, an intern working in Mount Sinai‘s Pathology Laboratory, believed that he had discovered an organism that caused typhus. He published a Letter in JAMA in 1914 outlining his research.

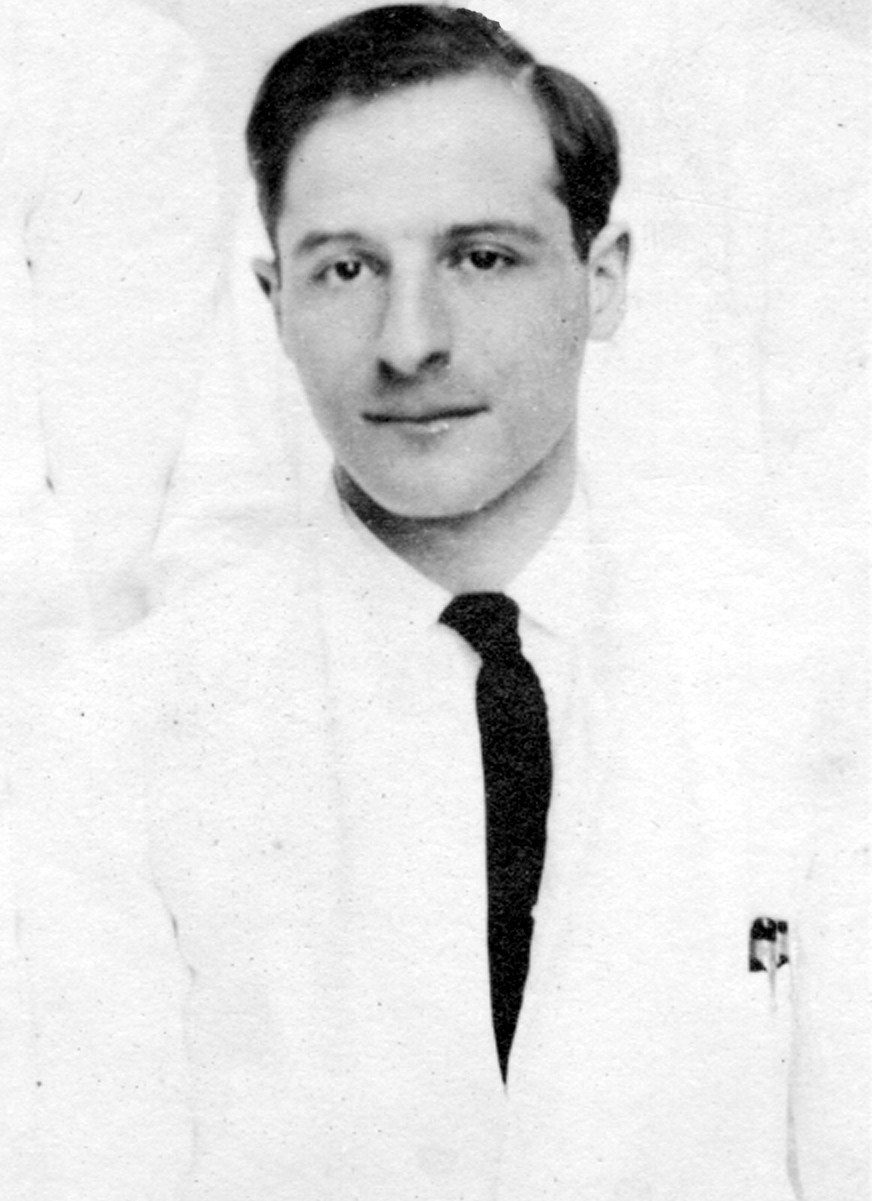

Harry Plotz, MD as a Mount Sinai intern in 1915

Since this was such an important public health problem, in 1915, Mount Sinai’s Trustees took the unusual step of agreeing to fund a trip to gather blood specimens in the Balkans, where there was a typhus outbreak – and the early stages of World War I. As noted in Wikipedia: “disease ravaged the armies of the Eastern Front, where over 150,000 died in Serbia alone. Fatalities were generally between 10% and 40% of those infected and the disease was a major cause of death for those nursing the sick.”

The research results of this trip were described by the physicians Harry Plotz and George Baehr in a 1917 paper in the Journal of Infectious Diseases. The details of the trip itself are described in the 1916 Annual Report of The Mount Sinai Hospital This narrative also describes an additional trip by Dr. Peter Olitzky to Mexico, also funded by Mount Sinai, when the researchers in Europe were taken prisoner by the Austro-Hungarian government. This lengthy quote provides the Trustee President of Mount Sinai’s description of the events of 1915-16:

In pursuance of my remarks of last year in regard to the typhus expedition to Serbia, I wish to state that Drs. George Baehr and Harry Plotz after many difficulties established a laboratory at Belgrade in a hospital directed by the American Red Cross. Thirty-six hours before the bombardment of Belgrade, they left for Uskub and there set up a laboratory in the Lady Paget Hospital, and shortly thereafter the town was occupied by the Bulgarians. Very soon afterwards they were invited by the Bulgarian and Austrian Governments to work under their auspices. They then left for Sofia and afterwards went to Vienna, Lemberg and into Russia….

Because of the fact that Drs. Baehr and Plotz during the first six months of their stay in Europe, practically did not come in contact with typhus fever, it was considered important to send a second expedition into Mexico to determine the cause of the Mexican typhus fever, and to carry on other work which at that time we were not sure could be carried on in Europe. The second expedition consisted of Drs. Peter K. Olitzky and Bernard S. Denzer, accompanied by Mr. Irving Brout, a laboratory helper, and the expedition was under the guidance and care of Dr. Carlos E. Husk, a prominent surgeon attached to the staff of the American Smelting & Refining Co. The expenses of the expedition were defrayed in part by Trustees of the Mount Sinai Hospital and in part by the American Smelting & Refining Co.

It was first decided to go to Aguascalientes, but after the expedition reached Matehuala it was determined to remain there, as even at that distance from the border the danger, because of dis- turbances of international conditions, was very great. Early in March, because of the increasing danger in which the men were placed, they were requested to return. The members of the expedition did not, however, leave, because Dr. Olitzky had been stricken with a severe attack of typhus fever. Very shortly thereafter, the plants of the American Smelting & Refining Co. throughout Mexico were closed down, and Dr. Olitzky had to be removed to Laredo, Texas. Just before the departure Dr. Husk, who had been of the greatest aid in the accomplishment of a remarkable piece of work within four weeks, also fell ill of typhus fever, and was brought into Laredo in a very serious condition. Dr. Olitzky after going through a most dangerous attack of the disease, recovered, but unfortunately it proved impossible to save Dr. Husk’s life.

During the course of this expedition the same germ was found in the typhus fever cases in Mexico as had been found in New York and as was found by the members of the European expedition in Serbia, Bulgaria, Austria and Russia. Apart from that, the typhus germ was cultivated repeatedly from lice, which have in recent years been considered the agent in transferring typhus fever from one person to another. Some further scientific studies were made, and vaccination done on a rather large scale. The results of the vaccination cannot be determined at the present time because of the unsettled conditions in Mexico.

In the end, no successful vaccine has been developed for typhus, but antibiotics and public health measures have made it a treatable, rarely fatal disease in the U.S.

The story of typhus and Mount Sinai is important because it shows the institution’s commitment to research and developing new treatments during times of crisis. As shown here, this commitment is not solely from the medical and scientific staff, but also from the Trustees and supporters of Mount Sinai. When times are dire, as in today’s COVID-19 pandemic, Sinai finds a way to enable the work to get done to advance medical knowledge and improve the treatment of patients.

Mar 23, 2018

A new finding aid for The Col. Henry H. M. Lyle Collection of World War I Photographs and Documents, 1916-1943, was recently published and made available to researchers on-line (http://icahn.mssm.edu/about/ait/archives/collection/henry-lyle). The collection includes 200 photographs from World War I, maps and documents used during the war, some correspondence, and reprints of articles by Lyle.

A new finding aid for The Col. Henry H. M. Lyle Collection of World War I Photographs and Documents, 1916-1943, was recently published and made available to researchers on-line (http://icahn.mssm.edu/about/ait/archives/collection/henry-lyle). The collection includes 200 photographs from World War I, maps and documents used during the war, some correspondence, and reprints of articles by Lyle.

The heart of the collection is the photographs taken in France during World War I, which depict often dramatic or surprising images of the war. There are views of hospital stations, barracks, and outdoor equipment (some include large defensive weapons), transportation of wounded soldiers, field dressing stations, supply trains, and troops on the battlefields. Interior views document soldiers, patients, operating rooms and special treatment rooms. A number of the images display the effects of mustard gas and other brutal wounds sustained by soldiers, while others capture the unit compound against the French countryside in an oddly artistic fashion. Still others provide a view of everyday life in the compound – washing clothes, unloading shipments of supplies and such, but which brings to life the challenges of a large group of people living in one spot at that point in time. Laundry meant picking lice off of clothes; unloading supplies meant huge piles of boxes; transporting wounded soldiers sometimes meant walking through ankle-deep mud. The collection also captures images of foreign soldiers in national uniforms, some riding horseback, a lifestyle that is very different from the standard U.S. soldier’s, which adds an interesting, and occasionally humorous, side to the war.

Henry Hamilton Moore Lyle, MD, was a noted surgeon and decorated soldier. He was born in Northern Ireland in 1874. His family immigrated to Ontario, Canada when Lyle was a boy. He graduated Cornell in 1896, and went on to Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, graduating in 1900. He took an internship at St. Mary’s Hospital for Children and at New York Hospital and a year’s surgical internship at St. Luke’s Hospital (1901-1902) before joining St. Luke’s surgical staff in 1904 and where he remained on staff until his death.

It appears that Lyle spent the year between his internship and surgical appointment traveling abroad, visiting clinics in Great Britain, France and the German-speaking countries. This familiarity with Europe may have led to his voluntary enlistment in World War I two years before the U.S. was formally involved in the conflict. In 1915 he took leave from his private practice and hospital positions in New York and spent six months as Chief Medical Officer of American Ambulance Hospital B, Juilly, France.

In 1916 he again took a leave and returned to France to serve for several months as Chief Surgeon of Ambulance d’Annel (Longueil, France). In April 1917 when the US entered the conflict, he joined the U.S. Army Reserve and in May was ordered to active service. In June he organized the United States Army Evacuation Hospital No. 2 at Camp Benjamin Harrison, and was appointed its commander when it left for France in January 1918.

In September 1918, Lyle was made Director of Ambulances and Evacuation of the Wounded for the First Army. During the ensuing Meuse-Argonne offensive, over 125,000 sick and wounded were brought to the railhead hospitals under his supervision. In recognition of his outstanding service, particularly during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, where the Evacuation Hospital No. 2 played a major role as one of two front line hospitals established in the Zone of Combat, he was decorated with the Distinguished Service Medal (U.S.). Lyle was also awarded the British War Medal and the British Victory Medal.

When the war ended Lyle returned to New York and medical practice at St. Luke’s Hospital, where his reputation as an outstanding surgeon followed his successes in battle. Lyle retired from medical practice in 1938, though remained a Consulting Surgeon at St. Luke’s until his death from coronary thrombosis on March 11, 1947.

Oct 7, 2016

(Click to expand the image)

Sixty years ago this month, The Mount Sinai Hospital said goodbye to the last of a group of 25 women from Hiroshima, Japan who had spent over a year at the Hospital having surgeries to repair injuries they suffered in the nuclear blasts that ended World War II. The group of young women were called the Hiroshima

Maidens, and the project that brought them from Japan to the U.S. was the brainchild of Norman Cousins, the Editor of the Saturday Review of Literature. He raised the funds needed for the project and enlisted the help of the Quaker community of the metropolitan New York region to house the Maidens when they were not in the Hospital. Three surgeons from The Mount Sinai Hospital volunteered their time (Drs. Arthur Barsky, Bernard Simon and Sidney Kahn), and the President of the Hospital, Alfred Rose, anonymously paid for the use of four hospital beds for the duration of the project.

The Hiroshima Maidens project was a milestone in postwar American-Japanese relations. Before leaving Japan, the girls were told by some that the American doctors were going to experiment on them. As it became clear that this was not the case, the donated funds were stretched to allow Japanese doctors to come to Mount Sinai and receive training in plastic and reconstructive surgery, thus helping to strengthen the field in Japan.

The Hiroshima Maidens project continued to have life. In 1995, one of the Maidens returned to Mount Sinai to meet with Dr. Simon. At that time she gave the Mount Sinai Archives a scrapbook of photocopies of images from Hiroshima after the blast. The next year there was a conference at Mount Sinai that celebrated the project from 40 years before, and highlighted Mount Sinai’s current international efforts. In spring 2005, for the 50th anniversary of the project, the last remaining Maiden and a group of Japanese press visited Mount Sinai once again. The group came to the Archives and looked at the photos from the 1950s and read again the newspaper accounts of the Maidens’ courageous journey to New York.

On this 60th anniversary, it is unknown if any Maidens are still alive. Still, it is comforting to know that the memory – and documentation – of the project lives on, and will not be forgotten.

Jul 21, 2016

The Mount Sinai Archives has received a large amount of new archival material over the last year, well over 186 feet of paper, photographs, and (sometimes) disintegrating leather-bound volumes. The bulk of these new collections contain material from Mount Sinai St. Luke’s Hospital and Mount Sinai West (the former Roosevelt Hospital), but they also include items documenting the Beth Israel Medical Center, Mount Sinai Queens, The Mount Sinai Hospital and the Medical School. Organizing, preserving and making available such a great quantity of material is a complex and time-consuming task, but the effort is well worth it, because these collections include many important historic treasures. Those treasures are the theme for a new Archives’ display in the Annenberg Building lobby. Here are some highlights from the display.

What makes a historical document or artifact a ‘treasure’? Sometimes, historical records provide information on an important person or an institution. The 1854 Bible belonging to the Rev. Dr. William Muhlenberg, founder of St. Luke’s Hospital, is an example of that, as are the newsletters and Annual Reports of the various Mount Sinai Health System hospitals that we have received. Other times, an item can be a ‘treasure’ because it provides context for what life was like at a specific period of time, highlighting how things have changed, or perhaps showing how some things never change. The Fathers’ Book from the Woman’s Hospital in the early 1940s does that, as do the reports created by the Mount Sinai Environmental Sciences Laboratory that are displayed. And sometimes what makes an item a ‘treasure’ is just that there is something appealing, unique or unexpected about it. Who would think that the Mount Sinai Archives has a World War II era U.S. War Department issued Japanese phrase book, currently on display in the Nursing case below the Stern Auditorium stairs? It is part of the papers sent to us by the daughter of Esther Winkler Shapiro, Class of 1944.

Perhaps the most surprising treasure we found as we put this exhibit together were the photographs and documents tucked into the back of a scrapbook from the Roosevelt Hospital School of Nursing, which was formed in 1896 and closed in 1974. This scrapbook, wrapped in the traditional blue stripe of the Roosevelt uniform, was created by Evelyn I.V. Howard, Class of 1908. The last few pages of the book include photographs and notes from Nina Gage, RN, a classmate of Miss Howard’s. These pieces document Gage’s years at a Red Cross hospital at the Hunan-Yale School for Nurses in Changsha, China from 1908-1915. There are photos of the facility as well as students and faculty members.

A view of one of the display cases showing Rev. Muhlenberg’s Bible in the far left corner and the Roosevelt nursing scrapbook in the middle.

If you are nearby, please stop in and take a look at our display. If you would like additional information, please contact us at msarchives@mssm.edu.

May 24, 2016

The cemetery at Base Hospital No.3 for Americans who died at the hospital, 1918

Memorial Day is set aside to remember the servicemen and women who have died while in service to their country. Ceremonies started after the Civil War and it became a national holiday after World War II. Since injury and death are a part of war, doctors and nurses have always been witnesses to the ravages of battlefields. The image above shows the American cemetery at Base Hospital No. 3, the Mount Sinai Hospital-staffed unit that served in France.

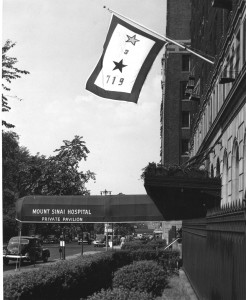

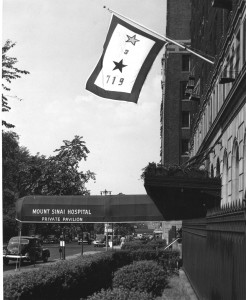

While the deaths happened abroad, the biggest impact was felt at home. It was not only families that marked their losses, but institutions as well. By World War II, service flags were a familiar patriotic symbol. The photo below shows Mount Sinai’s flag hanging from 1184 Fifth Avenue. The number on the bottom shows how many Mount Sinai doctors, nurses, staff and trustees were in the service at that time. The gold star at the top showed how many had died. By the end of the war, Mount Sinai’s numbers had grown to 802 served, nine dead.

The Mount Sinai Hospital service flag, 1944

Those nine are recognized here:

- Nils Carson

- Sydney C. Feinberg, MD

- Andrew Goldstein

- Jerome W. Greenbaum, MD

- Eugene M. Holleb, MD

- Goodell G. Klevan, MD

- Bernard Ritter, MD

- Helen Rogers, RN

- Stanley J. Snitow, MD