Oct 25, 2021

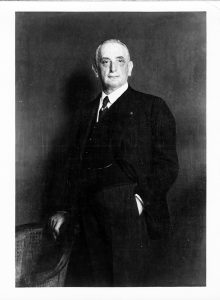

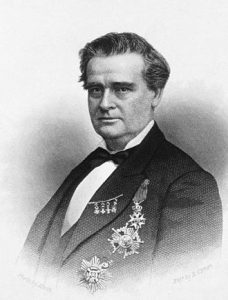

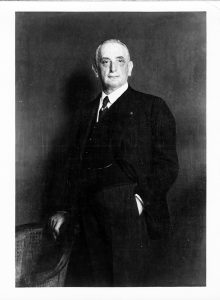

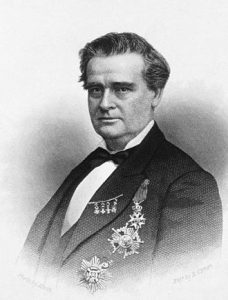

The Woman’s Hospital, often considered the first hospital in this country dedicated to treating the diseases of women, opened on May 4, 1855 in a house on Madison Avenue. It was founded by the currently controversial J. Marion Sims, MD, pictured right, in concert with a group of influential New York City women. Sims arrived in New York in 1853 from his home in Alabama, where he developed a procedure to close vesicovaginal fistulas. He relocated to New York in hopes of improving his own chronic health condition.

The Woman’s Hospital, often considered the first hospital in this country dedicated to treating the diseases of women, opened on May 4, 1855 in a house on Madison Avenue. It was founded by the currently controversial J. Marion Sims, MD, pictured right, in concert with a group of influential New York City women. Sims arrived in New York in 1853 from his home in Alabama, where he developed a procedure to close vesicovaginal fistulas. He relocated to New York in hopes of improving his own chronic health condition.

At first, Sims was welcomed into the medical community of New York and invited to demonstrate his fistula procedure. Unfortunately, once local doctors learned the procedure, they lost interest in him. Sims was unable to establish a strong practice or find a hospital that would offer him operating privileges.

The wife of one of Sims’ few medical friends in the city offered to gather a group of interested and influential women to discuss the state of women’s health care in the city. Thirty-Five women met on February 6, 1855, the outcome of which was the establishment of the Woman’s Hospital Association. The group would move to establish and direct a hospital devoted to the reception and cure of women suffering from “diseases peculiar to their sex.” The Association set up a Board of Managers, referred to as the ‘Board of Lady Managers,’ comprised of thirty-five women, to guide the Hospital. An Executive Committee of seven women, appointed by the Board of Managers, managed the day-to-day affairs of the institution.

In 1857 the Hospital was re-incorporated by the New York State Legislature as the Woman’s Hospital in the State of New York, and re-organized under an all-male Board of Governors. The twenty-seven Governors were responsible for the overall concerns of the Hospital, including filling vacancies of non-female staff, enacting the By-Laws and organizing the Medical Department. Women, however, were still very much in charge of running the Hospital. The former Board of Lady Managers became the Board of Lady Supervisors, and managed the operations of the Hospital, including the appointment of nurses and other female attendants. A smaller Board of Lady Managers remained responsible for handling the day-to-day business of the Hospital. By 1887, the Board of Governors invited four women from the Board of Lady Supervisors to join them. They found this integration “to be most acceptable in its results,” and soon after the Board of Governors was reorganized and evenly divided between men and women.

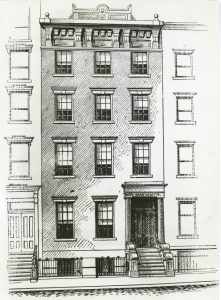

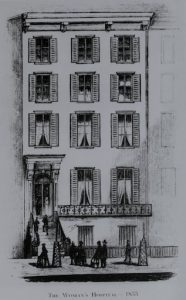

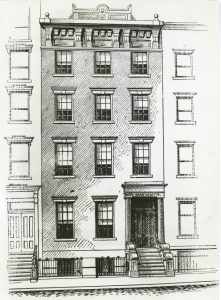

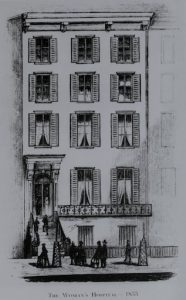

As mentioned above, the first Woman’s Hospital was a rented four-story brownstone at 83 Madison Avenue, off 29th Street, pictured left. The brownstone held forty beds and welcomed its first patient in May of 1855. The response to the Hospital’s opening was so great, by fall of 1855 that another surgeon, Thomas Addis Emmet, joined Dr. Sims as the second surgeon on staff. It wasn’t long before the Woman’s Hospital Board was seeking larger accommodations to meet patient demand.

As mentioned above, the first Woman’s Hospital was a rented four-story brownstone at 83 Madison Avenue, off 29th Street, pictured left. The brownstone held forty beds and welcomed its first patient in May of 1855. The response to the Hospital’s opening was so great, by fall of 1855 that another surgeon, Thomas Addis Emmet, joined Dr. Sims as the second surgeon on staff. It wasn’t long before the Woman’s Hospital Board was seeking larger accommodations to meet patient demand.

In 1858, approving the petition of Dr. Sims, the City of New York offered the entire block bounded by 49th and 50th Streets between Lexington and Park Avenues as a site for a new, larger hospital. Originally a Potter’s Field, or Stranger’s Burial Place, the plot was filled with coffins; more than 35,000 of them had to be removed. The first building, the Wetmore Pavilion, opened in 1867 and held seventy-five beds. A matching building, the Baldwin Pavilion, added in 1877, doubled that number. A Mr. Baldwin, who wished to remain anonymous, funded the construction of the second pavilion, contributing $84,000, provided the Association raised the balance of $50,000 to complete it.

Over the years, the Board recognized the need to develop additional services. A post-graduate school of nursing admitted its first class in 1888. The establishment of a hospital pharmacy in 1881, a maternity ward in 1910, and a social services department in 1912 are examples of the additional services made available at Woman’s Hospital.

Over the years, the Board recognized the need to develop additional services. A post-graduate school of nursing admitted its first class in 1888. The establishment of a hospital pharmacy in 1881, a maternity ward in 1910, and a social services department in 1912 are examples of the additional services made available at Woman’s Hospital.

The 49th Street location proved to be an unsatisfactory one, as the ground tended to be wet, and the basement and ground floors had leaks and dampness. In 1902, all hospital services, except the Out-Patient Clinic, were suspended and the facility was sold. (On a side note, the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel opened on this same plot in 1931.)

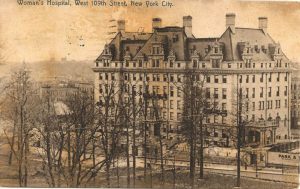

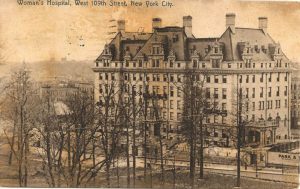

Hospital services resumed in 1906, when a newly constructed Woman’s Hospital opened on West 109th Street, between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues, pictured left. The hospital functioned here until 1965, when it moved just a few blocks north into a newly constructed building on the St. Luke’s Hospital campus at Amsterdam Avenue at 114th Street, pictured right.

Hospital services resumed in 1906, when a newly constructed Woman’s Hospital opened on West 109th Street, between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues, pictured left. The hospital functioned here until 1965, when it moved just a few blocks north into a newly constructed building on the St. Luke’s Hospital campus at Amsterdam Avenue at 114th Street, pictured right.

In 1952, realizing that their histories and ideals were parallel, and that it would be beneficial to each to consolidate their resources, which would also strengthen medical services offered to the broader Morningside Heights community, the Board of Trustees of St. Luke’s and Woman’s Hospitals decided to merge.

On January 1, 1953, the Woman’s Hospital became the Woman’s Hospital Division of St. Luke’s Hospital. The Board added “Center” to the Hospital’s name in the mid-1960s to acknowledge distinctions between the different Hospitals. The Woman’s Hospital Board of Governors merged with the corresponding board at St. Luke’s, but the Ladies Associate Board, which handled day-to-day business of the Hospital, continued to meet for some years.

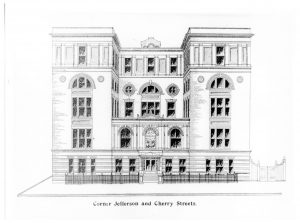

Architect’s drawing of Woman’s Hospital Division

In 1979, St. Luke’s Hospital Center merged with the Roosevelt Hospital forming St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center. In 1997, the Hospital Center joined with Beth Israel Medical Center under the Continuum Health Partners banner. In 2013, the Continuum Health Partners merged with Mount Sinai Medical Center forming the Mount Sinai Heath System. The Woman’s Hospital Division on St. Luke’s Hospital campus continued as such for a few years, but eventually duplicated services throughout the combined System. Services re-located, former names were changed, and Woman’s Hospital was consigned to history.

The Woman’s Hospital finding aid is available online here.

Oct 12, 2021

See Building Beth Israel, Part 1: Foundations and Part 2: Jefferson and Cherry for the first parts of this series. An interactive map of Beth Israel historical locations is available here.

The final years at Beth Israel Hospital’s Jefferson and Cherry Streets location were marked by some of the most defining moments of the early twentieth century. While it’s not clear exactly when conversations in favor of a new hospital began, the Beth Israel Board of Directors began to purchase property on Livingston Place along Stuyvesant Square Park as early as 1915. (Livingston Place would later be renamed Nathan D. Perlman Place after the U.S. Congressman and Beth Israel Vice President.)

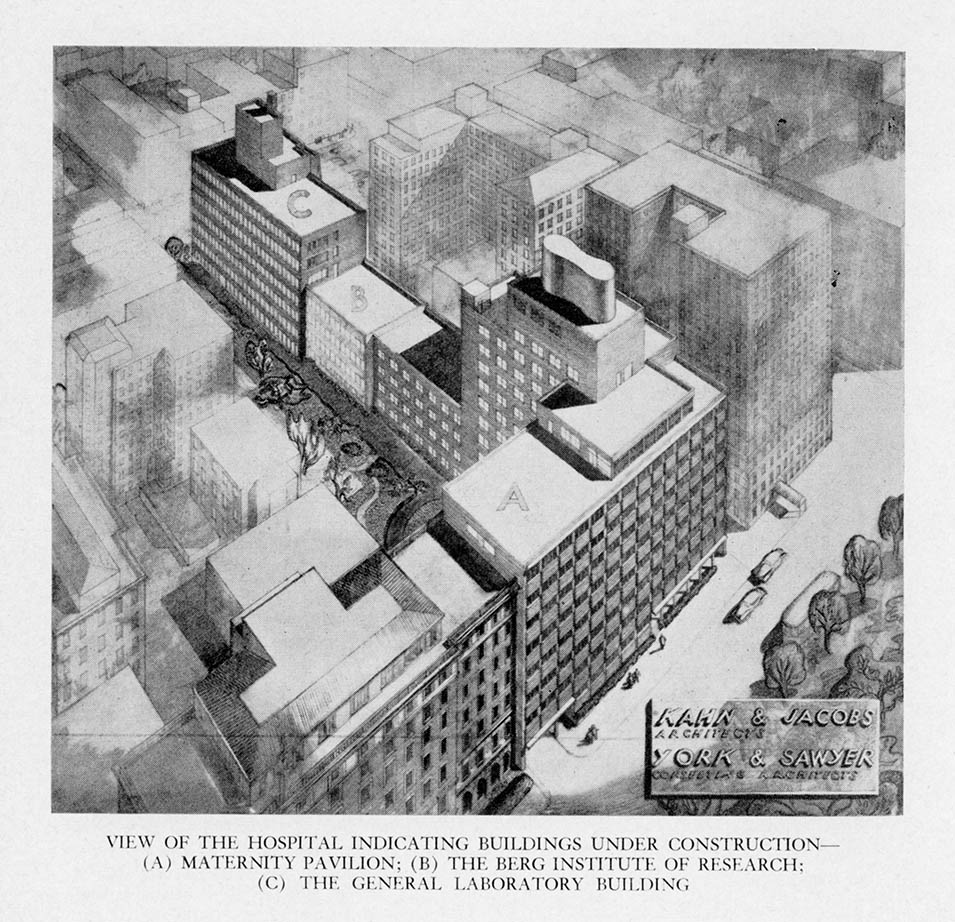

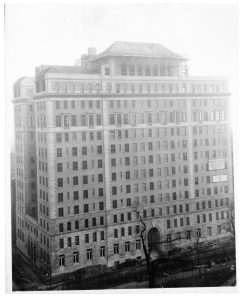

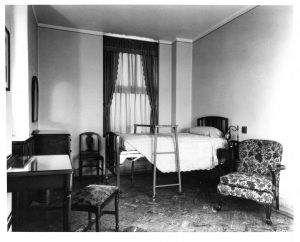

A primary motivation for the creation of what would become the Dazian Pavillion was likely related to hospital capacity – the thirteen-story building opened with nearly 500 private rooms and state-of-the-art facilities, a significant expansion over the 134 beds in wards at the Jefferson and Cherry Streets location. That said, justifications for the new building from the Board of Directors evolved from its earliest phases and its final construction in 1929. These reflect the many historical events of the era: modernization of health care, the introduction of the skyscraper, World War I and its aftermath, mass immigration, and the Influenza Epidemic of 1918.

The Tallest Hospital Building in the World

The Dazian Pavillion was conceived as a highly modern, state-of-the-art hospital building. At thirteen stories, it was the tallest hospital building in the world at that time. According to Islands of Compassion, Beth Israel “was the first to realize that a hospital skyscraper would mean freedom from the city’s noise and congestion.” This is evident in the discussions in the Board of Directors minutes. From March 16th, 1919:

It is of great concern to us to construct the new hospital according to the best methods of building; to provide the patients with as much comfort as possible, to serve them with palatable food, to provide them with fresh air and sunshine, to guard them from undue noise and excitement, and to keep the patient away from the smell and the workings of the Hospital – in a word, we are studying how best to care for the patient…The hospital of the future must be organized for prevention and not so much for cure.

World War I and its Aftermath

World War I was strongly felt at Beth Israel Hospital, with nearly half of the medical staff enlisted in the war effort. This continued throughout the war and beyond its end, and care for veterans presented itself as an early justification for a new hospital building. From the November 18, 1917 Board of Directors minutes:

The War presents the strongest argument for the construction of the new building. The War will last for some time and it is absolutely certain that there will be a great demand for hospital accommodation especially on account of the draft; deformities and disabilities are being discovered which require doctoring and good hospital care. The Beth Israel Hospital will be the only institution in the City to come up to expectations. We must be ready to receive cases on account of the epidemic that will surely follow the War and the new Hospital should stand as a permanent monument.

Beth Israel’s service to those affected by the war did not end with veterans. From the Board of Directors Minutes, October 17, 1920:

Congressman Siegel informed me that there are 200,000 Jews trying to secure passports for the United States. Orthodox Jews from Syria and Greece will come here in large numbers. That there are 15,000 Jews at Danzig awaiting transportation. If there is any doubt at all in the minds of anyone as to the necessity of a 500 bed Beth Israel Hospital for the treatment of Orthodox Jews this statement of Congressman Siegel should dispel them.

If Beth Israel was founded to care for Jewish immigrants in New York, the events following World War I only strengthened this resolve.

Influenza Pandemic of 1918

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918 was also a justification for the layout of the new building. The need for private rooms was a strong topic of debate in the years leading up to construction, within both the Board of Directors and the medical profession, considering hospitals largely operated out of shared wards at this time. The pandemic cemented the need for private rooms. From the Board of Directors Minutes, November 23, 1919:

…in respiratory infections…protection can only be obtained by safe-guarding one person from another, that the lesson derived from the severe experience of the recent Pneumonia epidemic is to the effect that such patients are not to be assembled into larged [sic] groups or kept in open wards but should be kept in separate rooms where they and their attendants may be preserved as far as possible from sputum droplet contamination.

The Dazian building would come to feature almost entirely private rooms.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the Dazian Pavillion took more than a decade to come to fruition. While many of the buildings and lots for the future space were purchased throughout the 1910s, there was significant slowdown in building progress due to the influenza epidemic. Building materials were also more expensive due to World War I.

On November 5, 1922 the cornerstone was laid. The ground was broken by Isaac Phillips, and future President Herbert Hoover, then U.S. Secretary of Commerce, were in attendance. The architect for the Dazian building was Louis Allen Abramson.

The building was finally opened in 1929. The Beth Israel Hospital School of Nursing (today the Phillips School of Nursing at Mount Sinai Beth Israel) moved into the 6th and 9th floors. Nearly 100 years after construction began, Dazian continues to be the home of Mount Sinai Beth Israel today.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Sep 28, 2021

See Building Beth Israel, Part 1: Foundations for the first part of this series. An interactive map of Beth Israel historical locations is available here. More archival material about the Jefferson and Cherry Streets location is here.

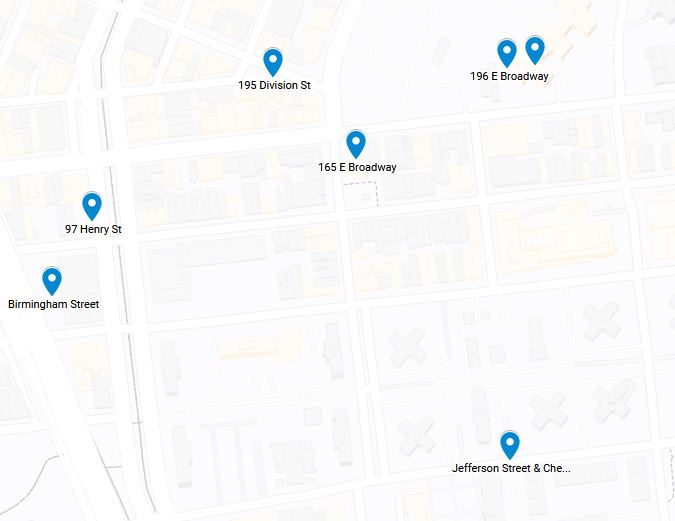

For much of the 1890s, the first decade of its existence, the location of Beth Israel Hospital was a moving target. The hospital moved from a factory loft, to an “old-fashioned parlor floor,” to two different rented hospital facilities. In its final locations during this period, split between buildings at 206 East Broadway and 195 Division Street, Beth Israel Hospital was financially solvent for the first time, enabling it to finally buy land of its own. In 1896, Beth Israel purchased a plot of land at Jefferson and Cherry Streets for the construction of a new hospital building.

In 1899, the Beth Israel Board of Directors chose a design for the new hospital. The cornerstone of the building was laid on April 1, 1900.

Much of the early funding for the new location was put up by Beth Israel’s Board of Directors, which, in addition to a mortgage, allowed for the purchase of the lot. However, the cost for the chosen design was well above initial expectations, and the final estimate was around $200,000 (about $6.5 million in 2021 dollars), requiring a significant fundraising effort.

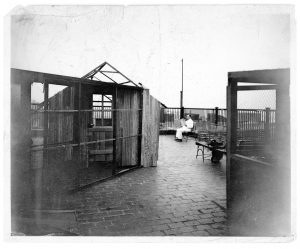

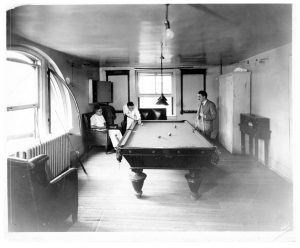

On May 26, 1902, the new Beth Israel Hospital at Jefferson and Cherry Streets was dedicated. It included 134 beds, with male, female, and maternity wards as well as private rooms. It featured a solarium, a common feature for hospitals at that time, in addition to outdoor space on the roof for staff and patient use. The Beth Israel Hospital Training School for Nurses was founded in 1904 and moved into this building. (Today, it is the Phillips School of Nursing at Mount Sinai Beth Israel.)

By August 1912, a physiological chemistry laboratory opened at Beth Israel under the direction of Max Kahn, PhD. The laboratory was located on the top floor and could comfortably hold five people. Additionally, after extensive delays, a children’s ward opened in January 1919, but it was forced to close six months later because of the nursing shortage caused by the Influenza Epidemic of 1918. Both the children’s and maternity wards were closed and re-opened periodically, based on available financial and staff support.

As early as 1915, the Beth Israel Board of Directors began to purchase property on Livingston Place along Stuyvesant Square Park. Plans to move to this new location were delayed first by World War I, and then by the influenza epidemic. Construction began in earnest in 1922, and Beth Israel finally moved to its current location in the Dazian Pavillion in 1929, giving up the Jefferson and Cherry Streets location. While it wasn’t the Hospital’s final location, Jefferson and Cherry Streets is where Beth Israel Hospital came of age and began to resemble the hospital of today.

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Sep 14, 2021

The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing diploma program officially closed 50 years ago in 1971. At that point, it had existed for 90 years and had graduated 4,700 students, including the one and only  male student in the last class. (A complete history of the School is available here.) Many hospital diploma schools closed during the 1970s, including the St. Luke’s Hospital and the Roosevelt Hospital Schools of Nursing, both in 1974. This wave of closings was due to the schools being fiscal drains on the parent hospitals, as well as the changing educational standards professional nursing organizations championed, including the baccalaureate degree as the best entry-level credential for nurses.

male student in the last class. (A complete history of the School is available here.) Many hospital diploma schools closed during the 1970s, including the St. Luke’s Hospital and the Roosevelt Hospital Schools of Nursing, both in 1974. This wave of closings was due to the schools being fiscal drains on the parent hospitals, as well as the changing educational standards professional nursing organizations championed, including the baccalaureate degree as the best entry-level credential for nurses.

By the mid-1960s, the Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing was at a crossroads, trying to find a way to move forward in the face of these trends. In 1967, the newly formed Mount Sinai School of Medicine affiliated with The City University of New York (CUNY). This triggered a review of other possible interactions between the two institutions. That year, the School of Nursing joined with Hunter College, a part of CUNY, to start offering elective humanities credit to the students, easing their path to an eventual baccalaureate degree.

The next twist appeared in the Hospital’s Annual Report for 1968: “This has been a milestone year for the Department of Nursing. Negotiations with the City University led to the joint announcement of a baccalaureate program in nursing to be launched in September 1969 with the [Mount Sinai] Director of Nursing holding the position of Dean of the School of Nursing. Alumnae, staff and students have all expressed enthusiasm at the forward step. They are particularly pleased at the acceptance of the name, The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing at The City College.”

And so it was, but only briefly. The first class was admitted to the program in fall 1969, along with a sophomore group that had started at Sinai, and a graduation ceremony was held in 1972 for thirteen students. However, the two institutions could not work out long-term arrangements and so the relationship was terminated by 1974.

And so it was, but only briefly. The first class was admitted to the program in fall 1969, along with a sophomore group that had started at Sinai, and a graduation ceremony was held in 1972 for thirteen students. However, the two institutions could not work out long-term arrangements and so the relationship was terminated by 1974.

The closing of the School left behind a saddened but vibrant Alumnae Association that continues to serve its members and The Mount Sinai Hospital today.

Aug 31, 2021

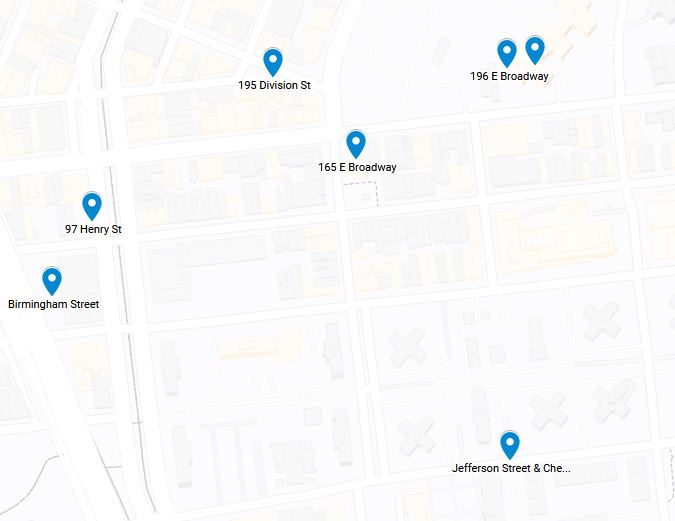

The first meeting related to the founding of Beth Israel Hospital was held on December 1, 1889 at 165 East Broadway. Healthcare was greatly needed in New York’s Lower East Side, whose residents, largely recent Jewish immigrants, were affected by poverty, close living quarters, and dangerous working conditions. From a 1901 essay on early Beth Israel history:

“The origin of the idea of this institution sprang from the poor themselves. So urgent was the need for such a local hospital, that in spite of the lack of support, and even of the discouragement of those in position to assume such a task, the poor themselves, by taxing their hard earned [sic] wages, gained by the sweat of their brows, established the association and undertook to support the Hospital…It serves to demonstrate the noble Jewish heart. These workingmen when they could earn their bread and butter were willing to contribute their 25 cents a month to help their neighbors in distress.”

In the face of “meagre [sic] and uncertain support,” the founders first endeavored to begin a dispensary, rather than a full-scale hospital, and in May 1890, rented a loft in a factory on Birmingham Street. (This street no longer exists, but today would be between Henry Street and Madison Street, just underneath the Manhattan Bridge.) The building was described as “most unsuitable and the accommodations about as poor as can be imagined” but still attracted more patients than could be treated, speaking to the great need for medical care in this neighborhood at the time.

Click here for an interactive map of Beth Israel historical locations

After two months at the Birmingham Street location, the Beth Israel outpatient dispensary moved to 97 Henry Street in July 1890. Described as an “old-fashioned parlor floor,” it was “much better situated” and the dispensary remained there for ten months.

Sketch of the 206 E Broadway location of Beth Israel Hospital, circa 1892-1902.

In May 1891, Beth Israel moved to 196 East Broadway. With twenty beds, this is the first Beth Israel location to include inpatient services in addition to the outpatient dispensary. The hospital includes two house staff: Abraham Hymanson, MD, is the first House Physician, and Wolfgang Kaplan, MD is Assistant House Physician.

Embroiled in a financial crisis, Beth Israel moves again in May 1892, splitting their services across buildings at 206 East Broadway and 195 Division Street. With lower rent and more space, including thirty-four beds, Beth Israel was financially solvent for the first time. The Division Street building was renovated one floor at a time for inpatient and outpatient use.

Beth Israel Hospital remained in this location for over a decade, before moving to its location at Jefferson and Cherry Streets in 1902, and finally its current location at the Dazian Pavillion in Stuyvesant Square in 1929. The history of both of these Beth Israel Hospital locations will be addressed in future posts.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Aug 18, 2021

The Upper East Side home of The Mount Sinai Hospital and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai spans continuously from 101st St down to 98th Street, with other buildings arrayed nearby. To achieve this continuous campus, what had once been 99th and 100th Streets between Madison and Fifth Avenues have disappeared. How and when did that happen?

View along 100th St., around 1937

The Mount Sinai Hospital moved to 100th Street in 1904, taking up the whole block between the avenues and up to 101st Street. In 1911, the Hospital started buying lots on the south side of 100th Street in anticipation of a large expansion program. By 1921, those new buildings stretched from Fifth Avenue across but not quite to the end of 100th Street. The street was used for physician parking, and in December 1949, New York City deeded the bed of 100th Street to Mount Sinai. It continued as parking for a few more decades, but with the construction of the Guggenheim Pavilion starting in 1986, the street disappeared into a plaza between the original buildings and the new.

The story on 99th Street is very similar: Mount Sinai had expanded to having buildings spread along the northern side of the block. At the end of the 1950s, when construction of the Klingenstein Clinical Center (KCC), fronting onto the corner of Madison and 99th Street, was being planned, Mount Sinai sought the help of the City, and in August 1958, the road bed of 99th Street was deeded to Mount Sinai.

And what about the former streets? Once the construction on KCC was finished, this area became known as the Hospital Gardens, and graduation ceremonies for our School of Nursing, as well as special events were held out there. The plaza across 100th Street was covered in bricks, and a large sculpture called La Sfera Grande by Arnaldo Pomodoro was placed there in 1974. In the late 1960s, all of the buildings along the former southern side of 100th Street and the northern side of 99th Street were torn down to make way for the Annenberg Building. The Gardens became Ross Park, and today the Sfera Grande sits adjacent to the Nathan Cummings Atrium in the Guggenheim Pavilion. This is only appropriate since Mr. Cummings had originally given Mount Sinai the sculpture.

Nursing School graduation in the ‘Gardens’ in 1961. Note that KCC is being built in the back left of the image.

Aug 3, 2021

On August 27th, it will be 165 years since the first baby was born at The Mount Sinai Hospital in 1856. The mother was a Mrs. Lichtenstein. She named the baby Isaac Touro, in honor of a Hospital benefactor, Judah Touro (1775-1854), who had helped support the young Jews’ Hospital in New York, as Mount Sinai was then known. (Judah Touro also gave money for the founding of Touro Infirmary in New Orleans and today’s Touro College and University System is named for Judah and his father Isaac.)

Isaac Touro Lichtenstein was one of two babies born in the Hospital during its first year of operation. Until the 1920s, most babies were born at home or in one of the specialized women and child care hospitals around the City. This meant that many general hospitals, including Mount Sinai, never felt the need to add a formal obstetrical service to their offerings, thus limiting the number of babies born at the hospital over the years.

By the 1920s, as hospital births began to rise around the country, the Mount Sinai medical staff started to talk to the Board of Trustees about adding obstetrics. As the doctors saw it, the problems arising from not having babies born at the Hospital were: the Gynecology staff could not admit their obstetrical patients to Mount Sinai; there was no obstetrical training for the GYN residents, nor was there training for the pediatrics residents in newborn care. The last also applied to The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing, which affiliated with the Sloane Hospital for Women so students could fill the gap in their education.

While the Trustees were increasingly sympathetic with the request to add an obstetrical service, it wasn’t until the middle of the 1940s that concrete plans were made for the erection of a new building to house obstetrics and gynecology, today’s Klingenstein Pavilion on Fifth Avenue. Every new building demands a fundraising campaign to make it a reality. Mount Sinai had just finished a major expansion that ended in 1922, with the addition of a new School of Nursing building and a semi-private pavilion seen as the next priorities. When these two buildings opened, the Depression was in full swing, which sapped Hospital and potential donor resources. This was followed quickly by World War II, but by the mid-1940s, the Hospital could see a window of opportunity on the horizon.

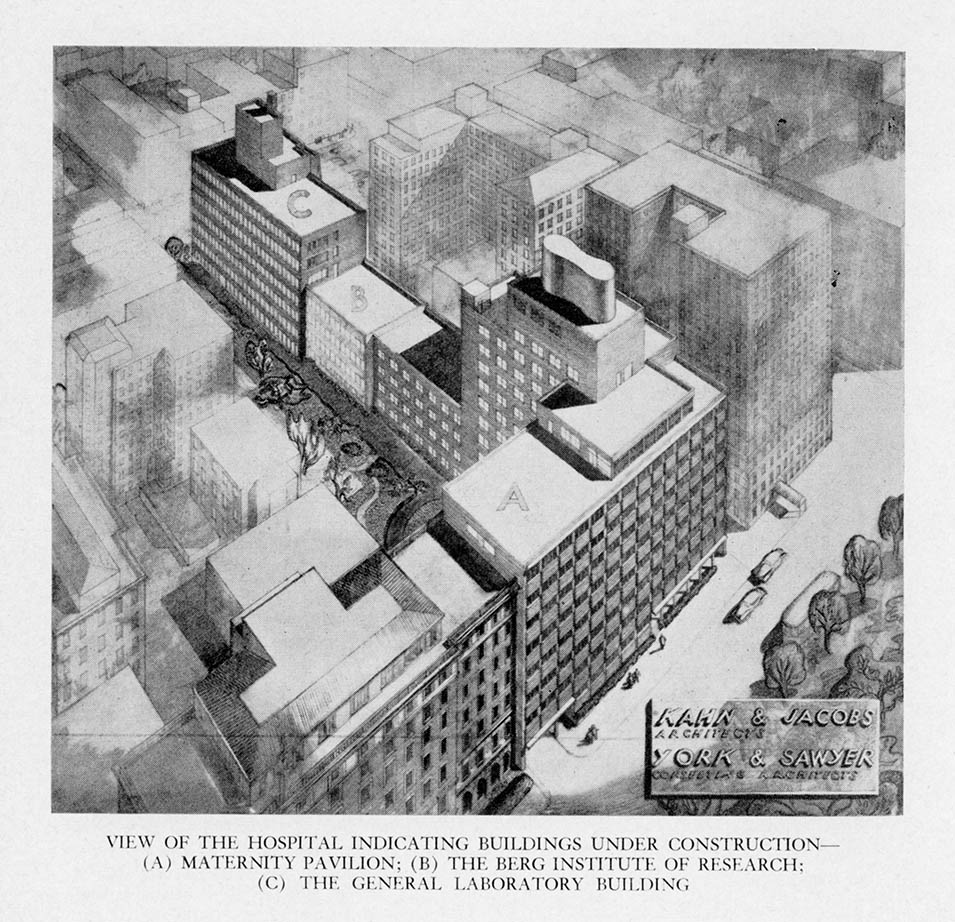

A fundraising campaign was begun when the war ended and on July 22, 1948, ground was broken for three buildings: the Klingenstein Pavilion, and the Atran and Berg Laboratories. In 1952, the obstetrical service started to operate as the building slowly opened. July marked the start of Mount Sinai’s first Prenatal Clinic, and the first prenatal clinic for women with diabetes in New York City started in the fall. The first OB patients were admitted in October, with the first baby born October 29, 1952 – 96 years after Isaac Touro Lichtenstein.

Jul 7, 2021

Among the several anniversaries the Mount Sinai Health System will celebrate this year, is the centenary of the establishment of the Radiotherapeutic Department at our Morningside campus. The Department was established under the direction of Dr. Francis Carter Wood, who was the Hospital’s Pathologist, and the director of that Department beginning in 1910 when it separated from the Medical Service, until 1948.

Wood was born in 1869 in Columbus, Ohio, into a medical family – his grandfather was Dr. Francis Carter of Columbus, and his great-grandfather, Dr. Francis Boake Carter, was the founder of Starling Medical College in Columbus, now a part of the Ohio State University. Grandson Francis Carter Wood graduated from Ohio State University in 1891. He enrolled in the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, and graduated in 1894. Between 1894 and 1896, when he joined the faculty of clinical pathology at Columbia University, he continued his studies in Vienna and Berlin. He was a friend of Mme. Currie’s, whom he probably met during this time, and became interested in radium therapy.

He returned home to join the staff of St. Luke’s Hospital in 1897, eventually becoming the Hospital Pathologist. Wood’s interest in radium therapy led him to become a pioneer in the use of X-rays and radium therapy for the treatment of cancer. In 1905 the X-ray department, which until that time had been under the Pathology Department, formalized as its own service, under Wood’s direction.

Dr. Wood established the Radiotherapeutic Department in 1921, while remaining director of Pathology. The department started with six Associates training under Wood’s leadership. Within 5 years, the department was handling over 1,000 patients a year. Wood served as director of both departments until his retirement in 1948.

Upon his death in 1951 at the age of 81, Donald S. Childs, M.D wrote of Wood, “His greatest contributions were educating the public to a proper attitude toward cancer, disproving sensational but false “cures” for the disease, and developing the three most effective methods of treating cancer – surgery, x-rays, and radium.”

Jun 21, 2021

I recently spent some time reviewing the President’s Report section of the Annual Report of The Mount Sinai Hospital from 1921 (linked here, starting on page 190). The President then was George Blumenthal, a devoted trustee, and a smart businessman who had recently guided the Hospital through a major expansion program, the uncertainties of World War I, and the influenza epidemic of 1918. Reading the report reminded me of the joys – and problems – with reading primary historical sources: it is very easy in hindsight to see connections between two times that may not be related, and simple observations can seem very prescient.

Don’t get me wrong, parts of the report are very dated and irrelevant to today: the Hospital was unable to afford radium to use in patient treatment, and so that service was not provided. There was also a section on issues related to fund raising through the Federation of Jewish Charities (today’s UJA-Federation). But still, there were many issues that would seem familiar to our current leaders. The Hospital was perennially short of money, but after the epidemic and the war, wages were rising quickly for what today would be called “essential workers”. Adding to this was a restrictive immigration policy that limited the labor pool. The inability to hire as many trained nurses as they needed was a continuing struggle as well, something the whole country recognizes today.

George Blumenthal, President of The Mount Sinai Hospital from 1911-1938

And yet Blumenthal made the case – as we do today – for why private hospitals like Mount Sinai deserve the philanthropic support of the people. He says:

It is absolutely essential that private institutions like Mount Sinai should be leaders of progress in hospital work…. To discover, test and demonstrate new methods of treatment is recognized as one of the functions of private institutions and it is one of the strongest reasons for their existence and constitutes their most important claim on the generosity of the public which supports them.

A couple of pages later, Blumenthal makes a bold statement about the importance of Mount Sinai being a teaching hospital. At this time it had loose clinical ties to both Columbia and NYU. He envisioned something more:

A Hospital possessing the clinical and laboratory resources of Mount Sinai should have university affiliation or if this be impracticable should independently utilize its organization for teaching purposes, for in no other way can the fullest benefits be derived from the intensive study of interesting, varied and often perplexing clinical material. We hope the day is not very far off when work on these lines can be done either through affiliation with one of the many teaching institutions located in our city or by independent action.

And “independent action” it was. Even with academic affiliations with various medical schools, in the 1950s Mount Sinai was not satisfied that they were living up to their potential in terms of training the next generation of physician/scientists or using their immense clinical material for creating new medical knowledge to advance patient care. In 1963, the Trustees received a charter to create their own medical and graduate schools. The Mount Sinai School of Medicine opened in 1968.

Jun 9, 2021

Nurses’ Week has come and gone, but it is always worthwhile to celebrate our healthcare warriors and shine a light on their accomplishments. This post would like to highlight Elise Galloway, a 1906 graduate of the Roosevelt Hospital School of Nursing who went on to be a Roosevelt nurse for her whole career.

Elise Galloway

Galloway was born in Garrison, New York in 1878. The farmhouse she and her family lived in until the 1920s still stands on the property of the Garrison Grist Mill Historic District site. As a student, she would have worked one of two shifts – 7a.m. to 7p.m. or the reverse – 7p.m. to 7a.m. Nursing students generally had one half day off a week, two hourly breaks a day and time on Sundays for church. The bulk of their training would be on their assigned ward. Their responsibilities included daily grooming and washing of patients’ faces, hands and feet, weekly sponge bathing, taking temperatures and noting that and any other particular changes in the patients’ condition, changing dressings, and serving patients their meals and preparing additional special dishes, if a patient needed supplemental nourishment. Nurses would join the Attending Physician on rounds, noting instructions and assisting as needed. Student nurses would also have weekly lectures in anatomy, physiology, Materia Medica, gynecology, the digestive system, the practice of medicine, the ethics of private nursing, and surgical diseases and emergencies.

RHSON Class of 1906 – I believe she is sitting below Miss Samuels who is in the back row, fifth woman in from the left.

Galloway graduated with the class of 1906, and began working at Roosevelt right out of school. Miss Mary Alexander Samuels, was the exacting Directress of Nursing in charge of both the nursing staff and the nursing school. Miss Samuels, considered a keen observer, recognized Galloway’s fine nursing skills, and heard about her reputation for reliability and an ability to catch on quickly – a necessary skill for a job that was learned by doing. She assigned Galloway as nurse supervisor over the Syms Operating Theatre.

The Syms Theatre, opened in 1892, was one of the most advanced operating theaters in the country and had very high standards. Medical students from the College of Physicians and Surgeons, located across the street from the Hospital, trained there, and visiting surgeons frequently came to observe surgical procedures in its sky-lighted amphitheater. As Nurse Supervisor, Galloway had to make sure all her student nurses knew how to properly sterilize instruments, suture materials, towels, and sheets for surgery, something that was a long and complex process at that time, as well as how to work with the surgeons during a procedure. Galloway, noted as being a patient and kind teacher, earned the nickname, “Mother Galloway,” used by students and doctors alike.

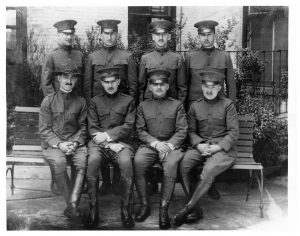

Her Hospital service was interrupted only twice in her career – the first time was in 1915, for six months, while Galloway volunteered to work in France with the American Ambulance Corps, prior to the formal U.S. entry into World War I. When the U.S. joined the conflict, Galloway served as a member of Base Hospital 15, which was composed of doctors, nurses, and support staff all drawn from Roosevelt Hospital’s personnel. She served as the Nursing Supervisor, organizing the operating room staff much as she did in the Syms Theatre.

Officers and Nurses of Base Hospital 15. Elise Galloway is on the left, standing next to the Unit Head wearing the Mountie-type hat.

The unit remained in Chaumont, France for most of the war. However, Galloway, along with another nurse and, two doctors spent about ten weeks at a French evacuation hospital at the French front near Vasney, where she experienced air raids at close range in exchange for valuable experience in wound treatment techniques.

Returning home to the Syms Theatre and New York, doctors knew her as an invaluable assistant and friend; nurses knew her as an excellent teacher. She was said to have an unfailing good temper, always calm, retaining poise in any emergency, and very unselfish, presenting the profession of nursing nobly and exemplifying the spirit of service and high standards that nursing is strives for.

The alumni newsletter notes that Elise Galloway left Roosevelt Hospital after an operation in the summer of 1933, and died in the Hospital on September 20, 1934 after an illness of several months.

The Woman’s Hospital, often considered the first hospital in this country dedicated to treating the diseases of women, opened on May 4, 1855 in a house on Madison Avenue. It was founded by the currently controversial J. Marion Sims, MD, pictured right, in concert with a group of influential New York City women. Sims arrived in New York in 1853 from his home in Alabama, where he developed a procedure to close vesicovaginal fistulas. He relocated to New York in hopes of improving his own chronic health condition.

The Woman’s Hospital, often considered the first hospital in this country dedicated to treating the diseases of women, opened on May 4, 1855 in a house on Madison Avenue. It was founded by the currently controversial J. Marion Sims, MD, pictured right, in concert with a group of influential New York City women. Sims arrived in New York in 1853 from his home in Alabama, where he developed a procedure to close vesicovaginal fistulas. He relocated to New York in hopes of improving his own chronic health condition. As mentioned above, the first Woman’s Hospital was a rented four-story brownstone at 83 Madison Avenue, off 29th Street, pictured left. The brownstone held forty beds and welcomed its first patient in May of 1855. The response to the Hospital’s opening was so great, by fall of 1855 that another surgeon, Thomas Addis Emmet, joined Dr. Sims as the second surgeon on staff. It wasn’t long before the Woman’s Hospital Board was seeking larger accommodations to meet patient demand.

As mentioned above, the first Woman’s Hospital was a rented four-story brownstone at 83 Madison Avenue, off 29th Street, pictured left. The brownstone held forty beds and welcomed its first patient in May of 1855. The response to the Hospital’s opening was so great, by fall of 1855 that another surgeon, Thomas Addis Emmet, joined Dr. Sims as the second surgeon on staff. It wasn’t long before the Woman’s Hospital Board was seeking larger accommodations to meet patient demand. Over the years, the Board recognized the need to develop additional services. A post-graduate school of nursing admitted its first class in 1888. The establishment of a hospital pharmacy in 1881, a maternity ward in 1910, and a social services department in 1912 are examples of the additional services made available at Woman’s Hospital.

Over the years, the Board recognized the need to develop additional services. A post-graduate school of nursing admitted its first class in 1888. The establishment of a hospital pharmacy in 1881, a maternity ward in 1910, and a social services department in 1912 are examples of the additional services made available at Woman’s Hospital. Hospital services resumed in 1906, when a newly constructed Woman’s Hospital opened on West 109th Street, between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues, pictured left. The hospital functioned here until 1965, when it moved just a few blocks north into a newly constructed building on the St. Luke’s Hospital campus at Amsterdam Avenue at 114th Street, pictured right.

Hospital services resumed in 1906, when a newly constructed Woman’s Hospital opened on West 109th Street, between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues, pictured left. The hospital functioned here until 1965, when it moved just a few blocks north into a newly constructed building on the St. Luke’s Hospital campus at Amsterdam Avenue at 114th Street, pictured right.

male student in the last class. (A complete history of the School is available

male student in the last class. (A complete history of the School is available  And so it was, but only briefly. The first class was admitted to the program in fall 1969, along with a sophomore group that had started at Sinai, and a graduation ceremony was held in 1972 for thirteen students. However, the two institutions could not work out long-term arrangements and so the relationship was terminated by 1974.

And so it was, but only briefly. The first class was admitted to the program in fall 1969, along with a sophomore group that had started at Sinai, and a graduation ceremony was held in 1972 for thirteen students. However, the two institutions could not work out long-term arrangements and so the relationship was terminated by 1974.