Jun 1, 2021

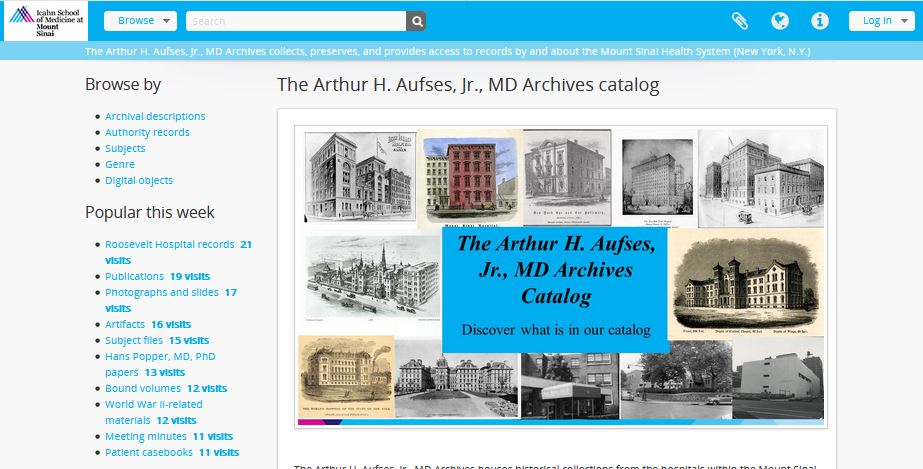

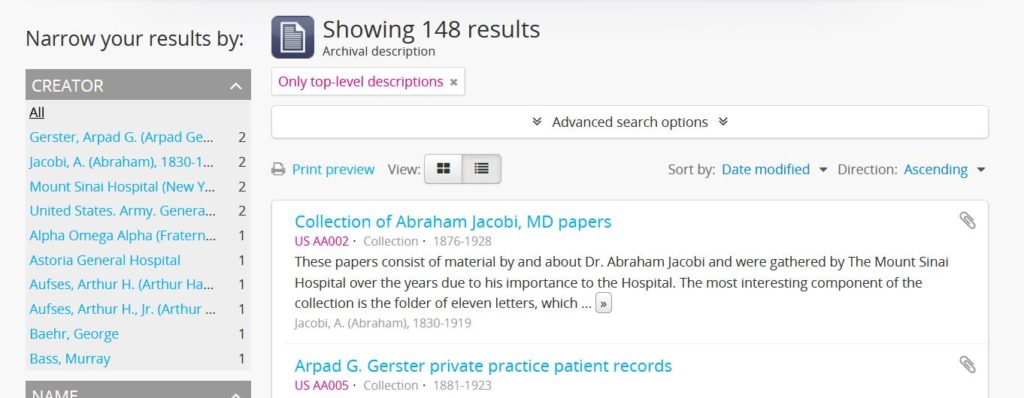

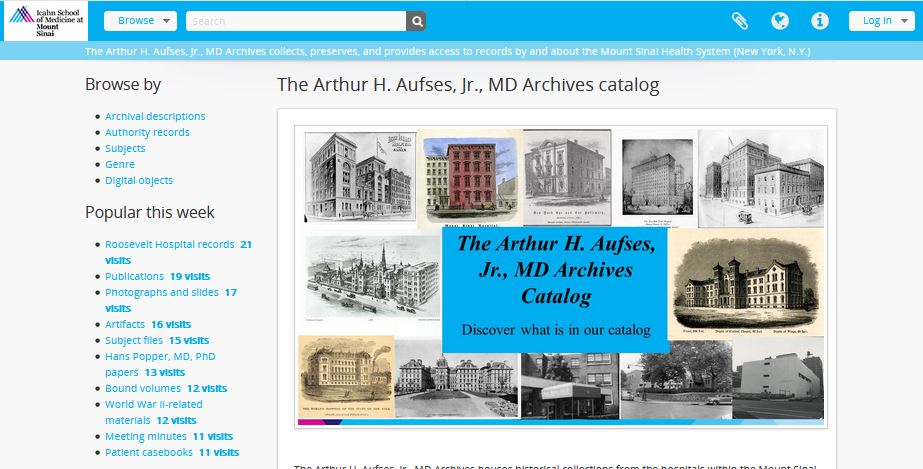

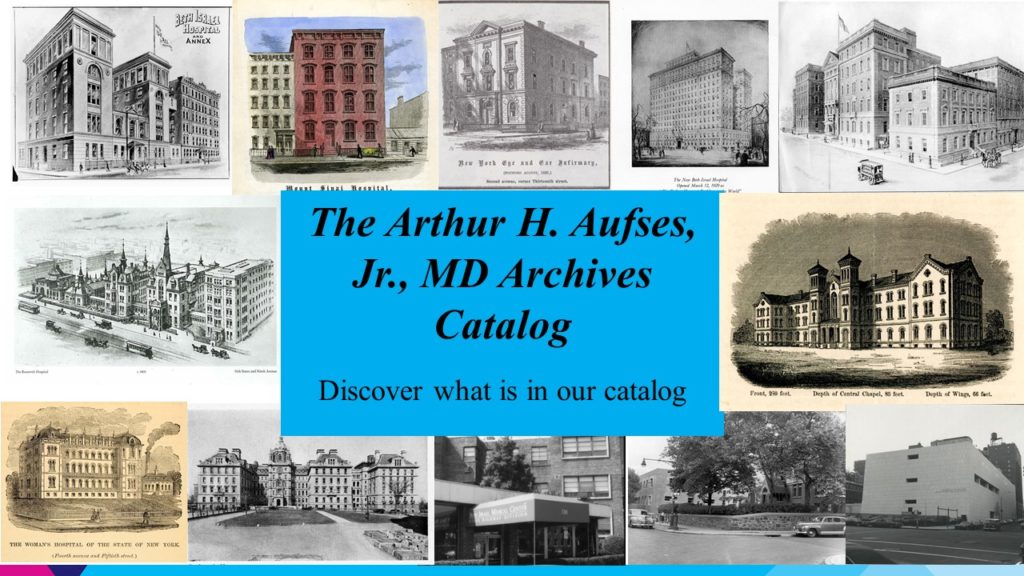

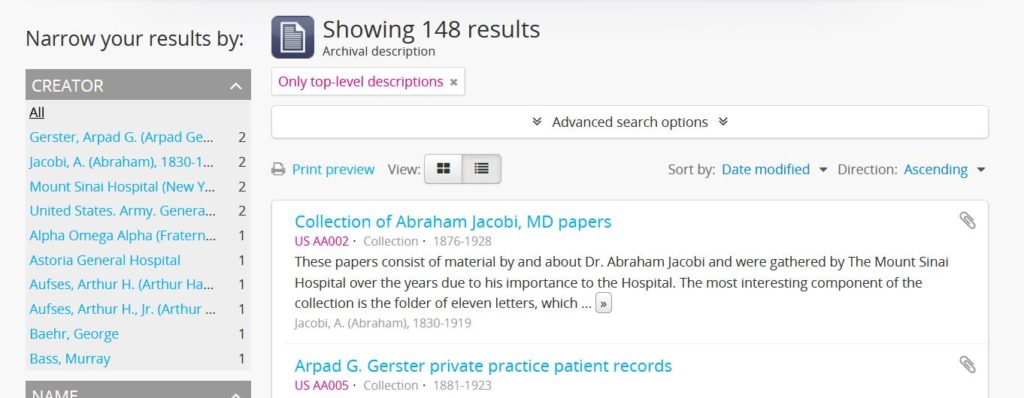

We are pleased to announce that the new Archives Catalog is live. Access it here to search or browse our collection.

You can read more about it in our previous post or consult the FAQ page for more information. Happy researching!

May 10, 2021

The Aufses Archives is excited to announce its new online catalog. Based in AtoM, the catalog will make available records for all our archival material and provide direct access to our digital objects.

What does this mean for researchers?

Our new catalog has several new features:

- A more complete view of our holdings: This is the first time all of our material will be described together in one place, regardless of format and digitization status. All our publicly available material will have a record, whether or not it has been fully processed or has a complete finding aid. (An archival record is like a record for a book in a library catalog – you might not be able to download the whole book from the catalog, but you can see that they have it and how to access it.)

- Centralized digital resources: All our digital material will be in one place, regardless of its original format. Researchers will only have to search in one place for our digital material. This includes our web archives collection.

- Names, subjects, genres: Looking for something really specific? Search results can be filtered and faceted to include specific people, topics, and formats represented in the archival material.

- Improved searching: Material will be findable via keyword searching, within and across collections. Advanced search will be particularly helpful for those searching for material within a particular date range.

When can I use it?

The catalog will go live on June 1, 2021, with the majority of our archival records. Our digitized audiovisual and image collections will be added over the course of Summer 2021. Our born-digital and digitized records then will be incorporated starting in Fall 2021, with a project completion date in early 2022.

I need help using the new catalog — and I have feedback!

Contact us! We’re happy to help you find what you’re looking for.

Update: As of June 1, 2021, the Archives Catalog is live and available here.

Apr 27, 2021

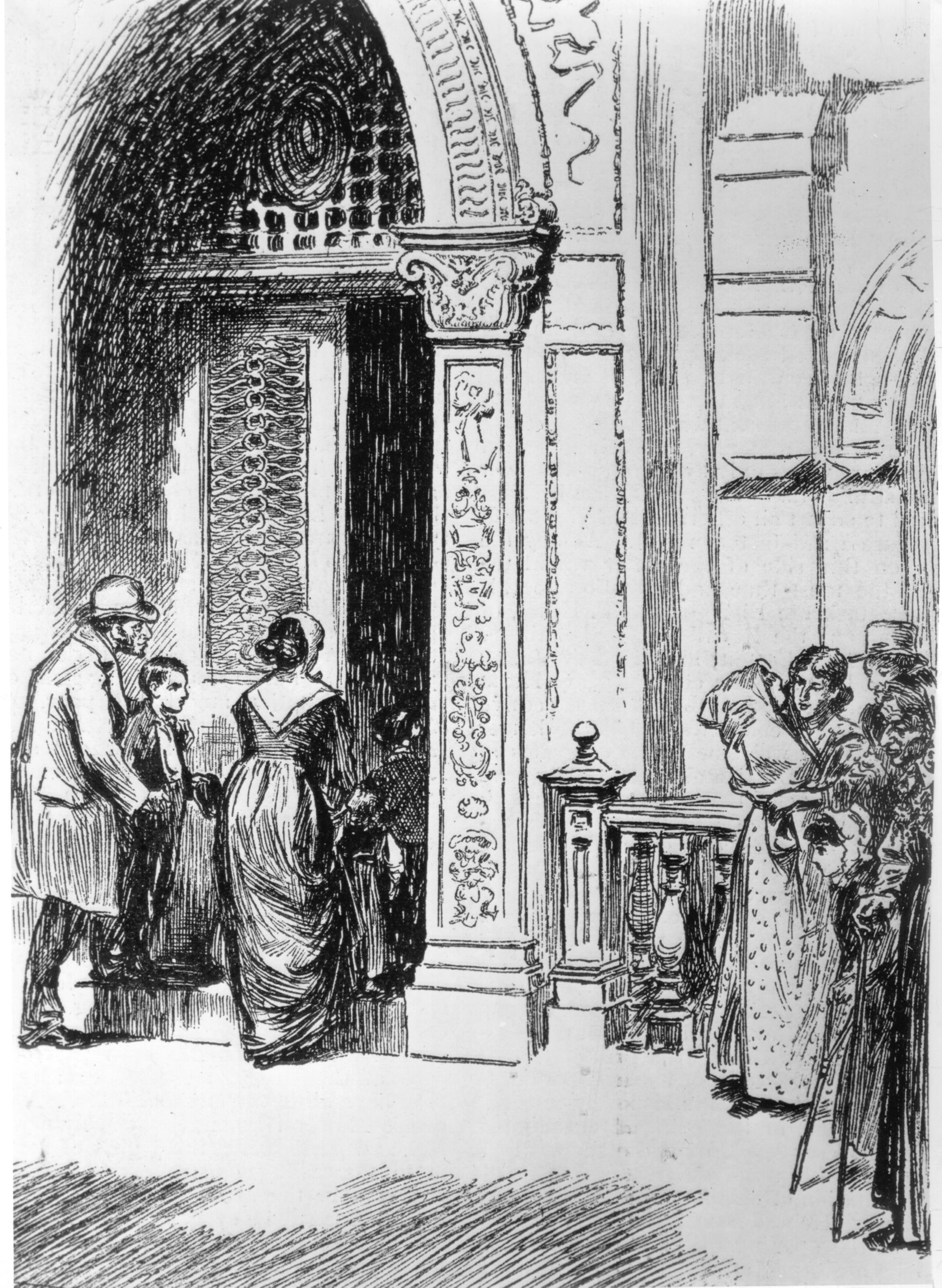

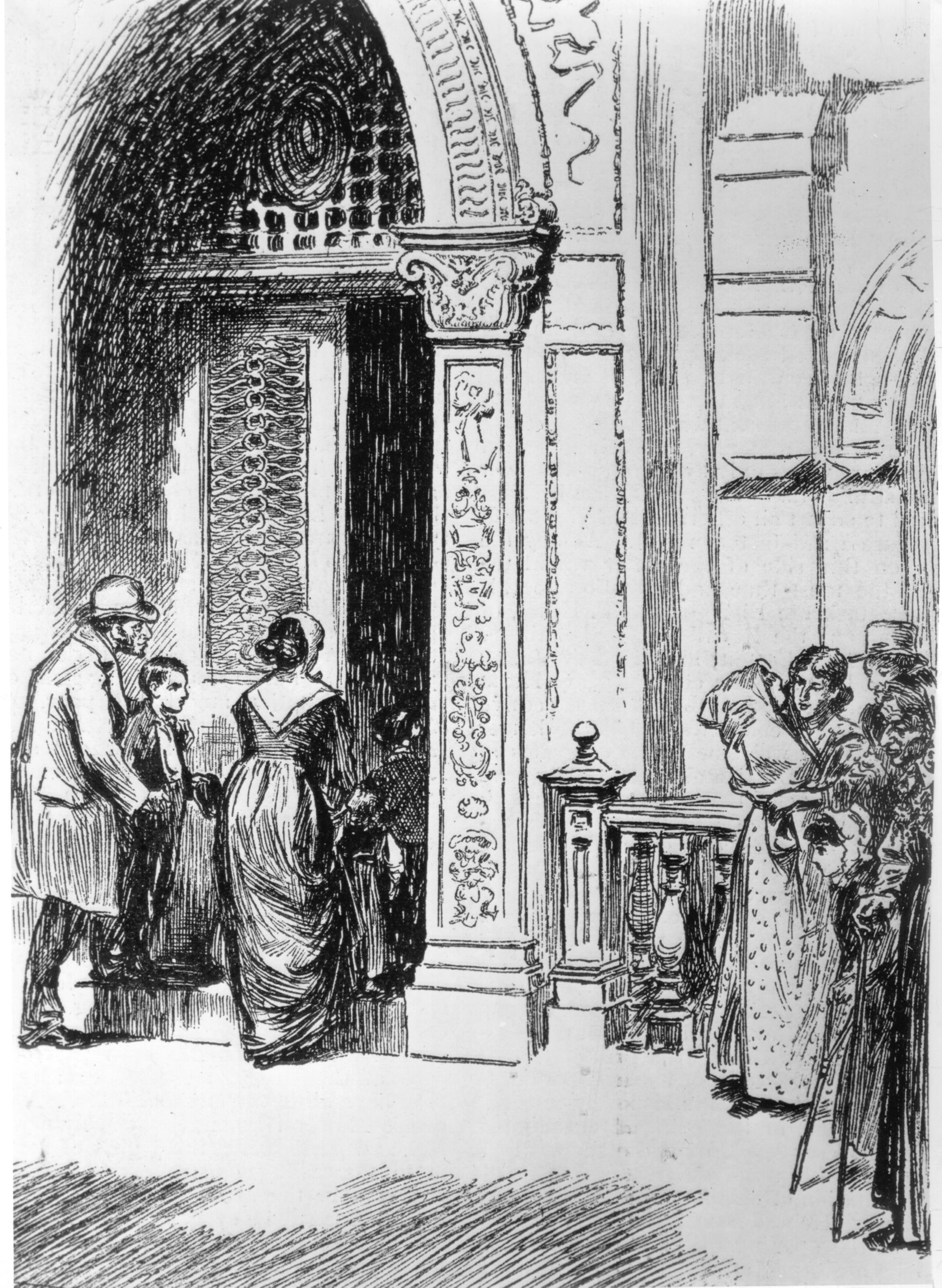

The Mount Sinai Hospital created its Dispensary/Out Patient Department in 1875 when it established four clinics: the Gynecology Clinic, the Children’s Clinic, as well as ones for Medicine and Surgery. Then as now, these clinics were designed to treat people with health needs that did not require a hospital stay. The Hospital traditionally had a long waiting list for admission, and this was seen as a way to help those they could before their conditions worsened. (In addition, in 1884, Mount Sinai Hospital created what it called the “Outdoor Visiting Physicians” to actually go to people’s homes to care for them there. Medicines were provided from the Hospital pharmacy.)

The Hospital was a charity organization and highly dependent on keeping costs down and maximizing donations to support its work. While there were a few patients willing and able to pay something for their care, the vast majority were treated free of charge both on the in-patient side as well as in the Dispensary. Since funds were so limited, Mount Sinai tried to take steps to ensure that their efforts were helping those most in need. One of those steps was to post a sign in the Dispensary that said, “Poor People Only Treated Here”. It eventually became clear that this sign was disrespectful to the people who used the clinic, and 140 years ago, on May 8, 1881, the Board of Directors of the Hospital decided to look into having the sign removed. Unfortunately, the Board minutes do not tell us if it was actually taken down.

The need to closely watch expenditures and try to reserve their services for the most needy continued to plague the Hospital leaders for decades. The beginnings of health insurance in the early decades of the 20th century helped, but it was really the implementation of Medicare and Medicaid in the mid-1960s that relieved hospitals of much of the burden of the costs of charity care.

The entrance to the MSH Dispensary, 1890

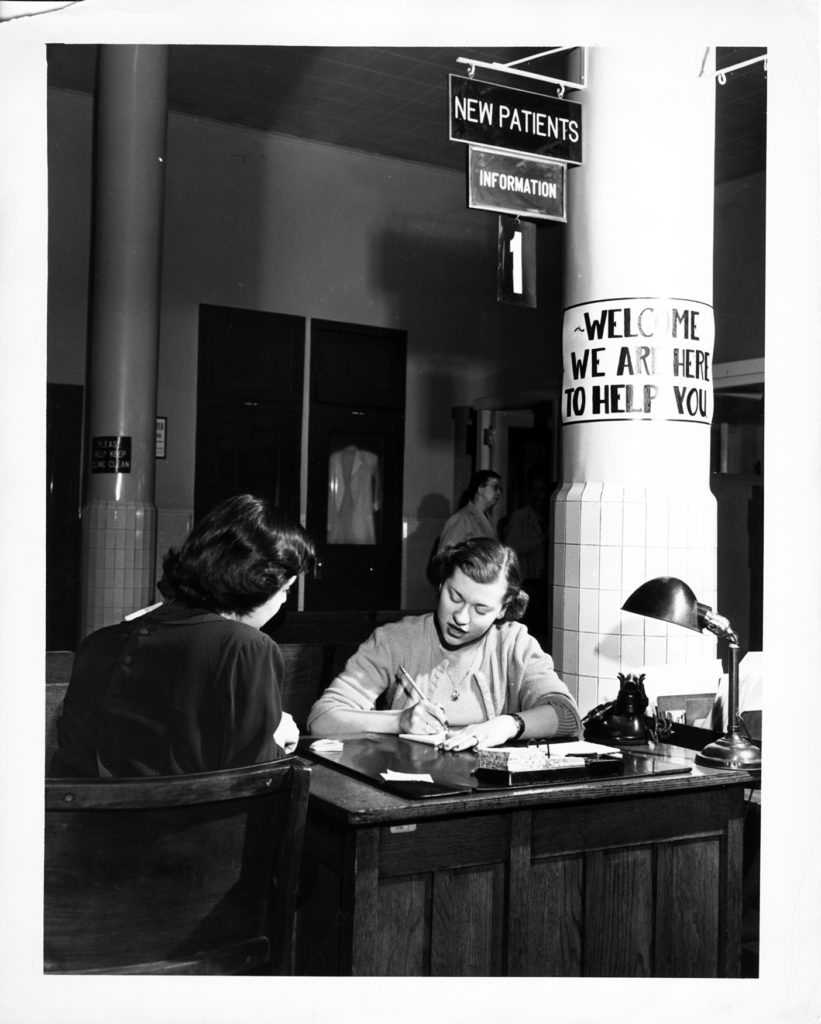

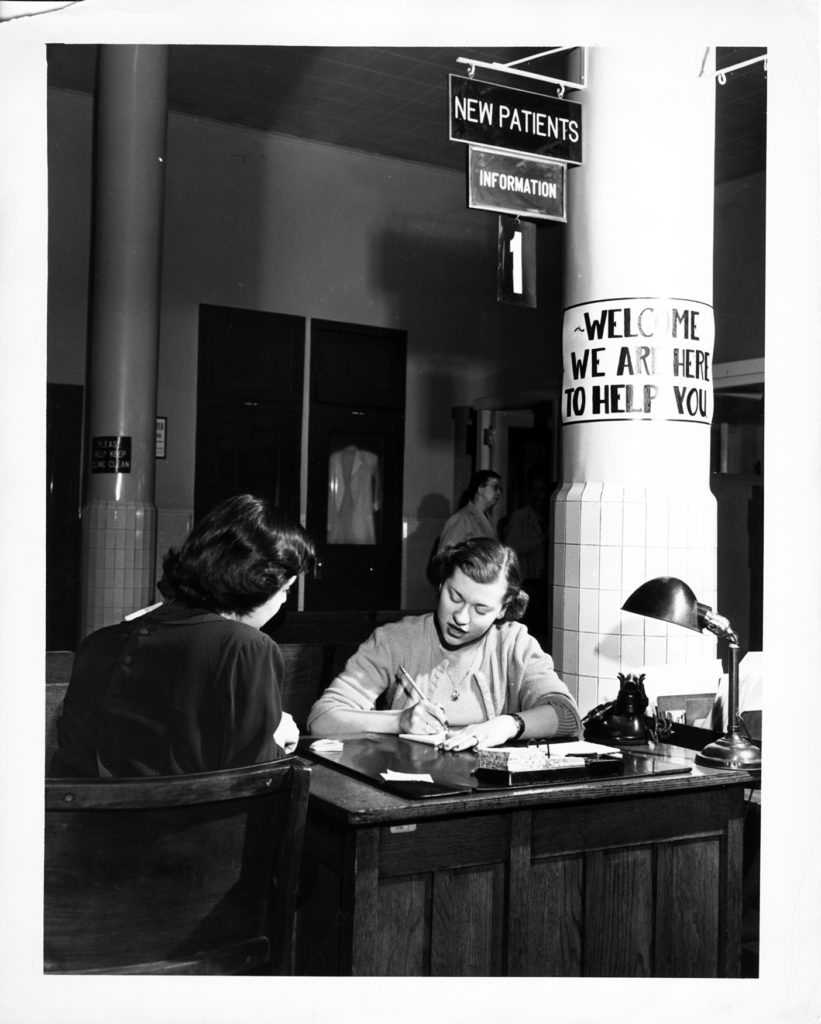

The Mount Sinai Hospital OPD Admissions desk in 1951

Apr 12, 2021

In today’s world, the only way to check into a hospital, without an emergency, is for a doctor to arrange for some kind of test or surgical procedure. But in the 19th century, hospitals functioned a bit like today’s walk-in clinics, at least in regards to admission. A person could come to the Hospital, speak with the Admitting Physician and request treatment for ‘X’ problem. But there were rules governing who would be accepted or refused.

By 1859, St. Luke’s published the first of their annual reports, which included reports from the Board President, The Pastor/Superintendent and the House Staff, along with lists of donations, occupations and diseases of those treated, and the publication of rules – for staff for patients and for visitors, and for Admission. Admission rules separated out patients with certain diseases. Those with contagious diseases were refused admission – this was a common practice for private hospitals at this time. The 1904 annual report is the first year the Hospital reported which applications were declined under the Rules of Admission, and their numbers. Ten persons were declined admission due to contagions like Erysipelas, scarlet fever and scabies.

Another group – the chronic or incurable – included paralytics, rheumatics, the mentally ill, incurable cancer patients, and those with an opium habit or delirium tremens, where also refused admission. Chronic cases in acute attack might be accepted, but were discharged once they returned to the ordinary health of one in that condition. Incurable cases might be admitted, but “only at the discretion of the Executive Committee of the Hospital.” These were also probably discharged as soon as they regained what was ordinary health for that condition. In 1904, 128 cases were refused admission to St. Luke’s for one of these reasons.

One exception to the rules was pulmonary consumptives (tuberculosis). In the 19th century, consumption was considered a hereditary disease, rather than a contagious one. The 1859 report of the Board of Managers, explains, “To provide for the incurably ill, particularly of this class, was one of the objects of the Hospital, and therein to supply an urgent want in the community… there was no resort for consumptives, so numerous in our climate, that St. Luke’s, as a church institution, felt bound to open to them her doors.“

The woman’s tuberculosis ward at St. Luke’s Hospital, circa 1900

The Pastor’s report often notes the comfort, and at times cure, these patients received, and their expressions of gratitude. In 1891, nine years after the discovery of the tubercle bacillus by Dr. Robert Koch, St. Luke’s accepted control over the House of Rest for Consumptives in the Tremont section of the Bronx, eventually moving all its patients to the main hospital and selling the property to support their care. Throughout the years annual reports note that consumptives made up to a quarter of the total census of patients in any given year.

These rules on admission disappeared early in the 20th century as hospitals’ ability to recognize and control germs was established, and as out-patient clinics opened to treat patients that might not have been admitted to the Hospital’s care in prior years.

Mar 26, 2021

Women have been active contributors to Mount Sinai Beth Israel since its founding in 1890. From the Ladies’ Auxiliary formed in MSBI’s first year of operation, to the first female House Staff member Dr. Nettie Shapiro in 1909, to so many on our front lines today, women’s contributions have always been essential to the operation of the hospital. This year for Women’s History Month, we’ll be featuring Dr. Marie Nyswander (1919-1986), a psychiatrist and an early leader in methadone maintenance in the treatment of heroin addiction.

Dr. Nyswander was born in Reno, Nevada, and graduated from Sarah Lawrence College (1941) and Cornell University Medical College (1945). From there she joined the Public Health Service in Lexington, Kentucky, where she first worked with patients with addiction issues. She later received psychiatry training at New York Medical College, and published a book, The Drug Addict As A Patient, in 1956. The book was among the first which argued for treating addiction as a medical problem, rather than a moral failing, likely influenced by the dramatic increase chemotheraputic treatments for psychiatric disorders in the 1950s. She went on to chair the New York City Mayor’s Advisory Board on Narcotics in 1959 and worked at a clinic in East Harlem throughout the early 1960s, alongside her own private practice.

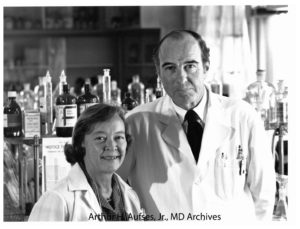

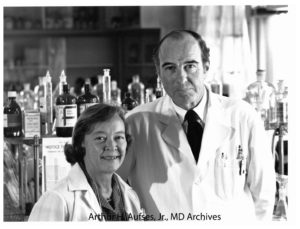

Photograph of Drs. Nyswander and Dole

In 1964, she was invited by Dr. Vincent Dole, a physician at Rockefeller Hospital, to join a study on the biology of addiction, which ultimately led to the discovery of methadone as a treatment for heroin addiction. Drs. Nyswander and Dole married in 1965. From the late-1960s until her death in 1986, she was affiliated with Beth Israel Hospital, where thousands were eventually treated through the Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program. She also served on the President’s Advisory Board for Mental Health during the Carter administration. Both she and her work with Dr. Dole received many honors.

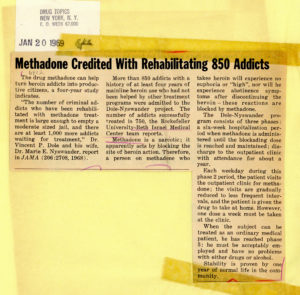

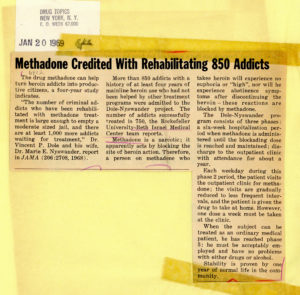

Article from January 20, 1969 issue of “Drug Topics”

Dr. Nyswander was a fierce defender of what has been a controversial treatment since its inception. Though detractors argue that methadone replaces one opioid addiction for another, Nyswander and Dole saw that abstinence-focused treatments were not always effective and that the symptoms of withdrawal caused by detoxification were needlessly challenging and painful for the patient. Methadone, an opioid itself, prevents drug cravings and blocks the ‘high’ of heroin.

Dr. Nyswander passed away in 1986 at the age of 67.

Sources:

Courtwright, David T., “The prepared mind: Marie Nyswander, methadone maintenance, and the metabolic theory of addiction,” Addiction 92, vol. 3 (1997): 257-265. Accessed March 23, 2021.

Dole, Vincent, Biographical photographs, Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

“Dr. Marie Nyswander Dies at 67; Expert in Treating Drug Addicts,” The New York Times (New York, N.Y.), April 21, 1986. Accessed March 23, 2021.

Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program clippings, AA088.S003.SS001.B003.F029 – AA088.S003.SS001.B003.F047, Mount Sinai Beth Israel collection, Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Mar 15, 2021

In April we celebrate both Women’s History Month and national Social Work Month. So it is fitting that we highlight a woman at Mount Sinai who was also a pioneer in social work, Miss Doris Siegel (1914-1971). Mount Sinai’s Department of Social Services (later Social Work) was created in 1907 and, since it was still a new field of service, the Department was initially managed by a series of nurses. By the mid-20th century, this was no longer the case, and in 1954, Doris Siegel was named Director of the Department. During her tenure, she updated and expanded the services of the Department, and spent time on broadening educational efforts in social work.

Doris Siegel, 1969

When Mount Sinai School of Medicine was forming in the 1960s, a new entity was created called the Department of Community Medicine (today’s Department of Environmental Medicine and Public Health). In 1968 the Social Services was moved into Community Medicine as the Division of Social Work. In this new role, the mission of Social Work was to support the School through innovative community service programs, research, and participation in medical student education. (They had been training nursing students from the beginning.) These were all activities that staff in Social Work had been doing for many years, and being an official part of the School supported and encouraged them to continue.

In 1969, social work at Mount Sinai as an academic enterprise was recognized with the creation of the Edith J. Baerwald Professor of Community Medicine (Social Work), the first endowed chair in social work in an American school of medicine. (It was a gift of Jane B. Aron, a Trustee at Mount Sinai and a long-time supporter of Mount Sinai’s Department of Social Work.) Doris Siegel was installed in the chair at a special convocation ceremony in 1969, making her the first woman named to an endowed chair at Mount Sinai. She died two short years later, but is still remembered today as a “Pioneer in Social Work.”

The Baerwald Chair remained in the Division of Social Work through the tenure of two more Directors, Helen Rehr and Gary Rosenberg. Meanwhile, the broader Department had evolved and changed its named several times. In 2017, the Baerwald Chair in Social Work became the Baerwald Professor of Environmental Medicine and Public Health.

Mar 1, 2021

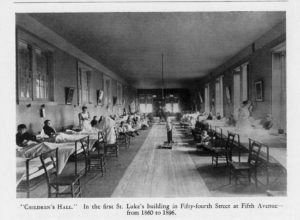

When St. Luke’s Hospital was in the planning stages, it was Rev. Muhlenberg’s wish that the Hospital maintain a mission of charity, and that no suitable applicant be turned away, regardless of his or her ability to pay for treatment. The wards for men and women were designed with large windows to allow in sunshine and fresh air, as it was felt that these elements, along with good food, were essential for providing a cheery atmosphere in which to recover good health.

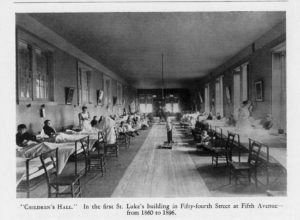

However, the Managers soon realized a need they had overlooked: the number of sick children needing treatment. The 1860 annual report notes that one of the smaller rooms was set up as a Children’s Hall, to separate youngsters from the adults, which makes sense, as they probably needed more attention from the nursing staff.

However, the Managers soon realized a need they had overlooked: the number of sick children needing treatment. The 1860 annual report notes that one of the smaller rooms was set up as a Children’s Hall, to separate youngsters from the adults, which makes sense, as they probably needed more attention from the nursing staff.

The Trustees’ report for 1865 lists two big wants: “more room for sick children, because the apartment given them is always more than full” and “a ward for boys above the age of childhood, who are now mixed with adults, but in view of their moral interests, ought to be separate.” Judging by later reports, this may have been for boys below the age of 15 years. Annual reports list as many as 150 children needing care a year.

Many of the children brought to St. Luke’s had orthopedic problems, particularly hip joint diseases, and spinal issues. The first specialty services established at St. Luke’s was Orthopedic Surgery, opened primarily to treat pediatrics patients such as these. However, the mission of the Hospital was to treat and heal, and these cases often required prolonged rehabilitation on-site. The Board of Managers reached out to Hospital benefactors for solutions.

In 1868, the Hospital received the gift of a country estate in King’s Park, Long Island, courtesy of Mrs. C.L. Spencer and her niece Miss Wolfe. Called St. Johnland, it was a convalescent home for crippled or disabled children and many of the children of St. Luke’s went there to rehabilitate, recuperate, and enjoy the fresh air and sunshine of the country environment. Later annual reports note that children at St. Johnland did the typesetting and printing of these reports, which suggests that some children had trade training, perhaps so they could earn a living once they were discharged from Hospital care.

Another concern of Rev. Muhlenberg and the Board of Managers was care for the infirm elderly, especially elderly men with no family. Part of St. Johnland became a nursing home for them, answering both concerns. St. Johnland functioned as a rehabilitation home for children until the early 1950s, when its Board of Trustees decided to focus on the elderly population exclusively. St. Johnland still functions as an elder care center today.

In the mid-1880s to mid-1890s, a large summer cottage in Great Neck, Long Island was made available to St. Luke’s as a convalescent home by the generosity of Mrs. And Mrs. Edmund C. Stanton. Sick children from the Hospital spent their summers there, away from the heat and closeness of the city with accompanying nurses. A Hospital Attending made weekly visits to check on the children. Other summer homes were loaned to St. Luke’s for use as convalescent homes from time to time.

In 1925, Mrs. Hicks Arnold donated her estate of several hundred acres in Greenwich, Connecticut, called Byram Woods, to St. Luke’s Hospital. It came with an additional one million dollars for the construction of a convalescent hospital and the establishment of an endowment for its upkeep.

The Byram Hills Convalescent Home opened in 1927 and provided a healthy place to recuperate in a country setting, with the requisite fresh air and sunshine for hundreds of children. As times, and medical practice, changed and the Byram Hills facility aged, it eventually became outdated. In November 1964 Byram Hills was closed and sold.

Feb 16, 2021

Each January the Aufses Archives starts the New Year by installing a new exhibit highlighting events at Mount Sinai that are reaching a milestone anniversary. In 2021, that includes the celebration of the 175th anniversary of the founding of St. Luke’s Hospital (today’s Mount Sinai Morningside) and the 150th anniversary of the opening of Roosevelt Hospital (today’s Mount Sinai West). The Archives’ staff uses images and original documents to illustrate the most important events, and tries to stick to ‘round number’ anniversaries, e.g. the 25th, 50th, 100th, etc.

Sadly, each year, that leaves us with a group of interesting milestones that are celebrating a ‘not quite a big year.’ Here are a few of those ‘misfit’ milestones for 2021.

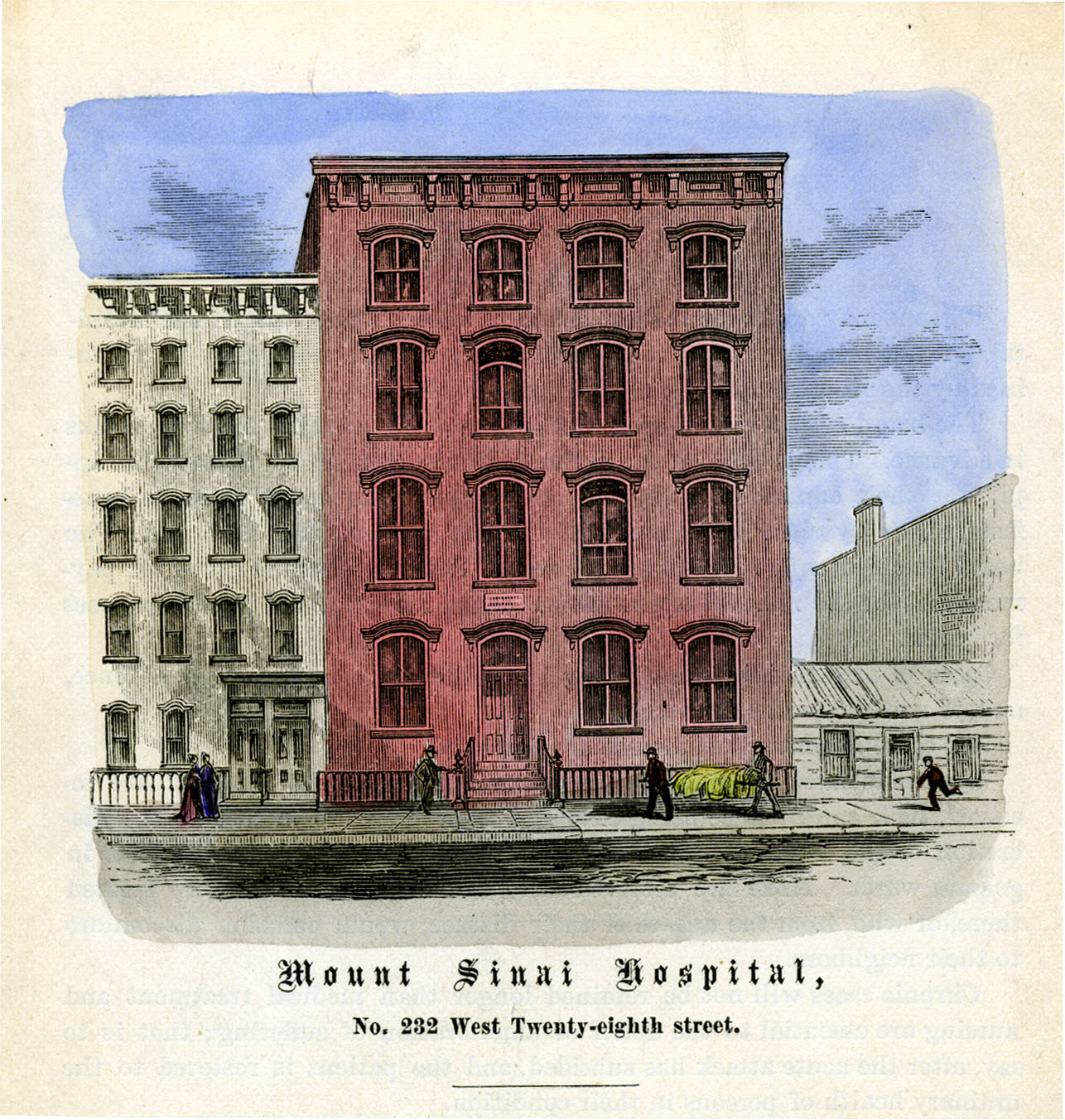

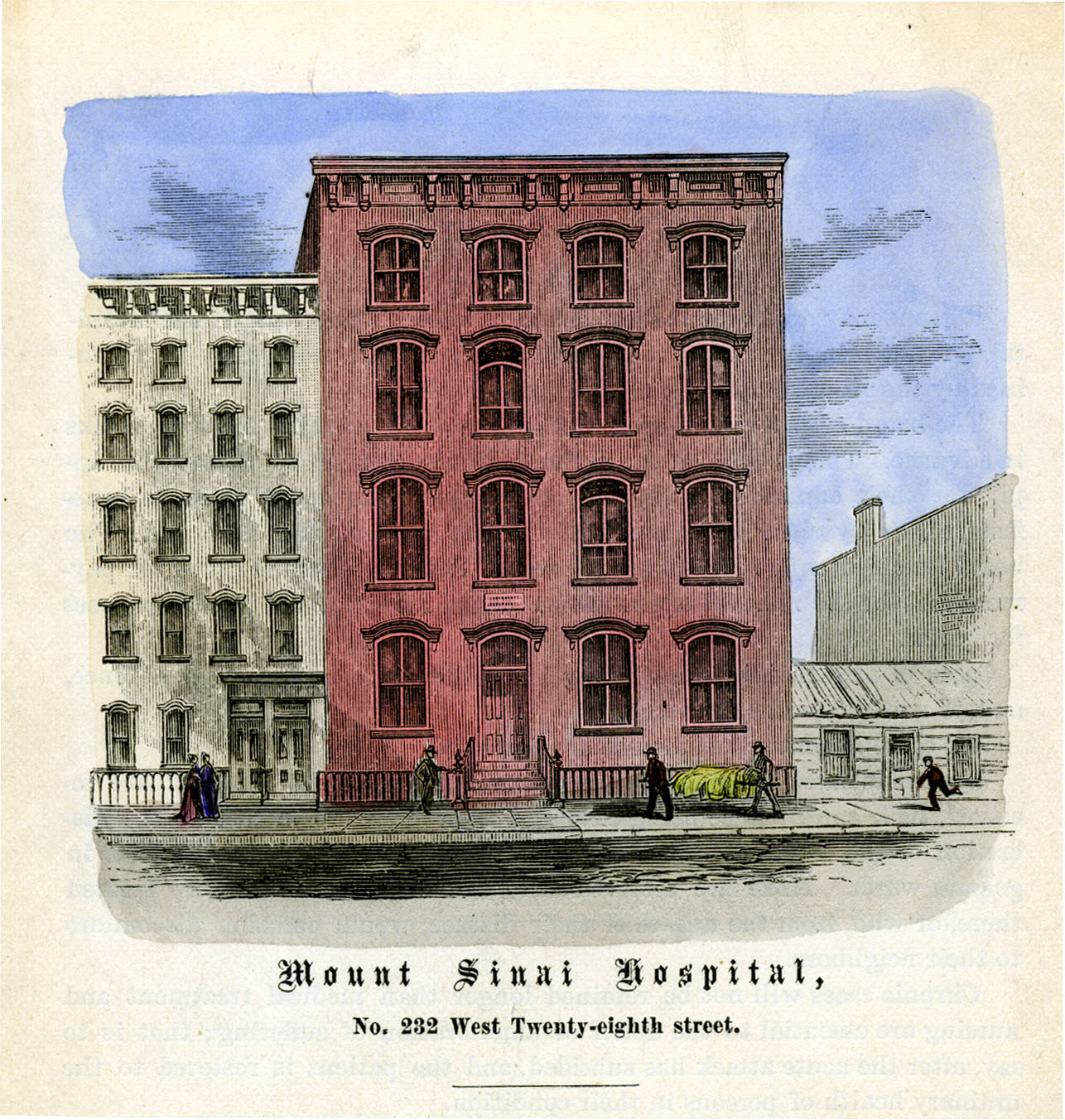

1856 – 165 Years Ago

In its first full year of operation, The Jews’ Hospital, later The Mount Sinai Hospital, admitted 216 patients with 129 cured and 14 deaths. Of the 216 admissions, 16 were pay, 200 free. There were two births. The first baby born at the Hospital was called Isaac Touro, in honor of a bequest to the Hospital from him. The patient census varied from a low of 9 to a high of 28. The budget for the year was $5493.76. There were nine paid staff members: two doctors, a Superintendent, nurses, cooks, and domestics.

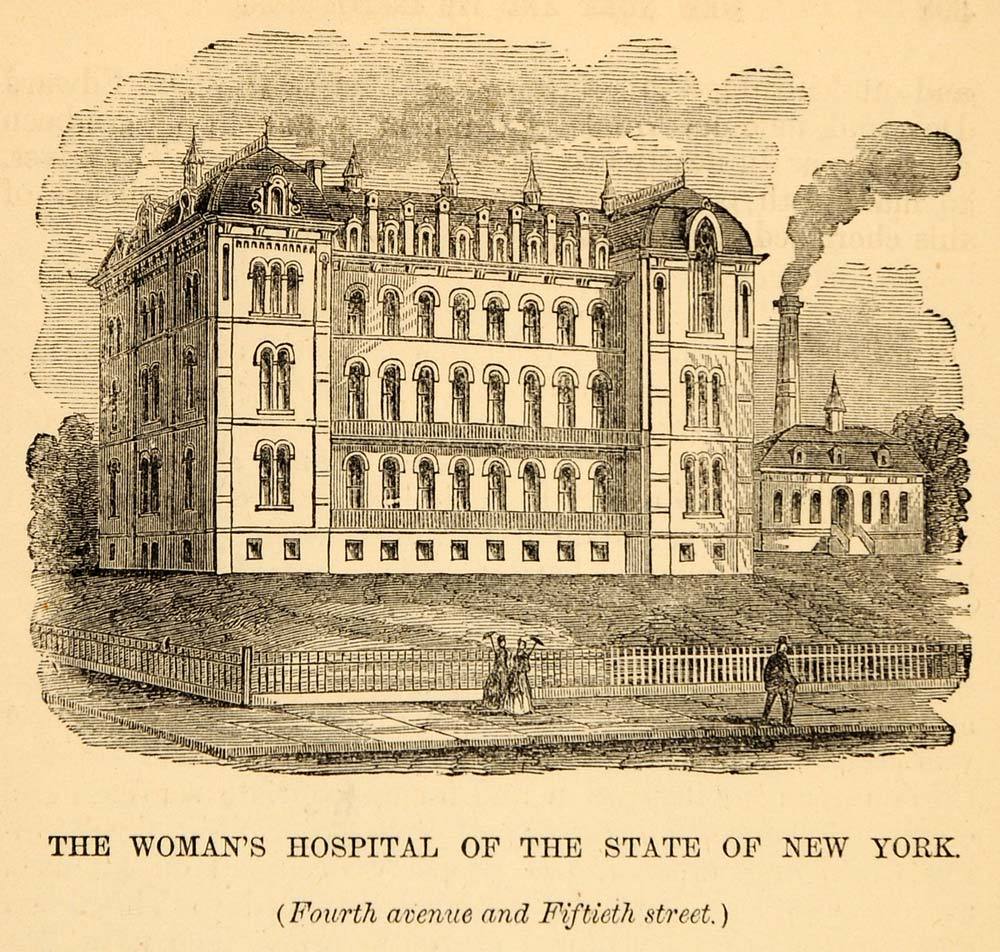

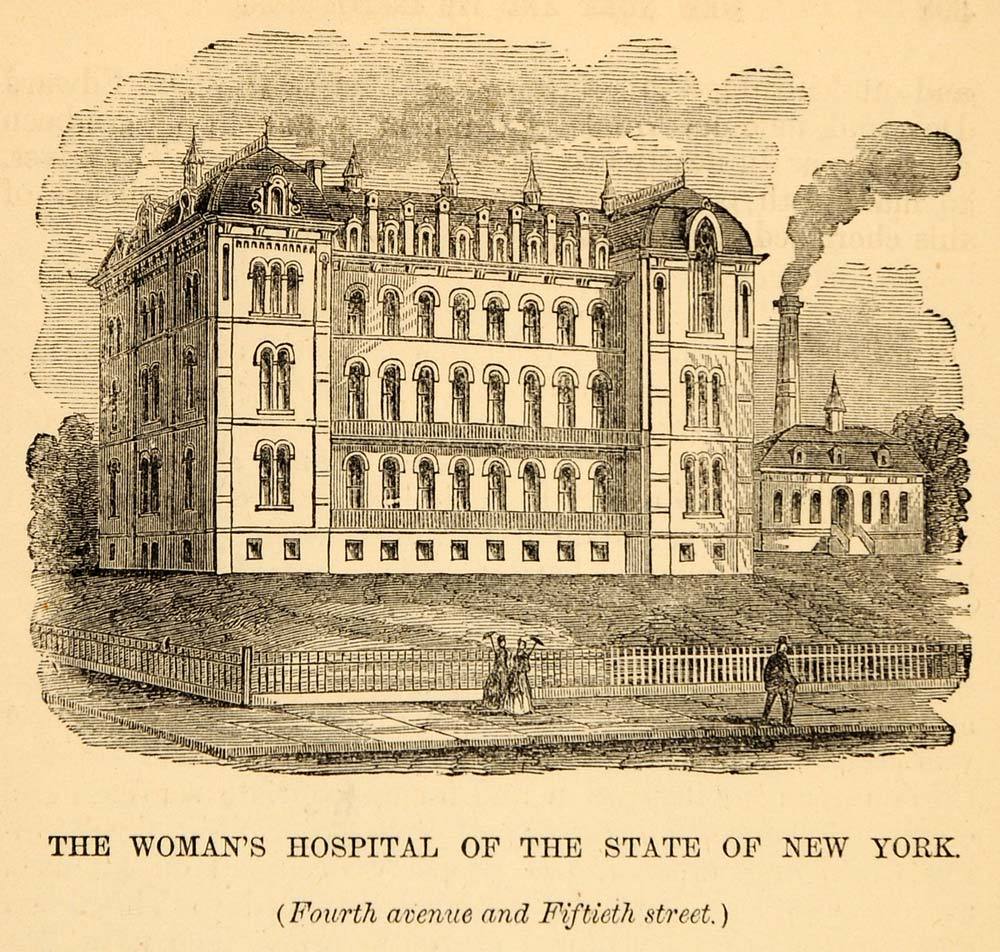

1866 – 155 Years Ago

May 23: the corner stone was laid for a new building between Lexington and Fourth Avenues and 49th and 50th Streets to house the Woman’s Hospital in the State of New York, an institution that would later merge with St. Luke’s Hospital. The City of New York had conveyed the deed to this block to the hospital in 1857. It had been a Potter’s field or Stranger’s Burial Place and filled with coffins. It was noted that more than 35,000 had to be removed before the hospital could be built.

1871 – 155 Years Ago:

On July 12, The Mount Sinai Hospital cared for 25 people injured in the nearby Boyne Day riot, which saw Ulster Scots Protestants holding a parade, protected by NYC Police and State National Guardsmen, with Irish Catholic laborers protesting the celebration. Over 60 people died and more than 150 people were wounded, including 22 militiamen, 20 policemen injured by thrown missiles, and four who were shot, but not fatally.

1881 – 140 Years Ago

William Halsted, MD, organizes an outpatient ‘dispensary’ (Out Patient Dept.) in the basement of the main Admin building at Roosevelt Hospital and remains its director until 1886.

1891 – 120 Years Ago

May 10: Beth Israel Hospital moves to 196 Broadway. This is the first BI location to include inpatient beds in addition to an outpatient dispensary; there are twenty beds. The hospital includes two house staff to provide 24 hour care.

1906 – 115 Years Ago

Beth Israel’s Dazian Pavilion in the 1930s

The Beth Israel Hospital Social Service Dept. is created.

1936 – 85 Years Ago

A Department of Hematology established at the Beth Israel Hospital under the direction of Dr. Louis Greenwald.

1946 – 75 years ago:

The Mount Sinai Hospital opened the first lab in this country dedicated solely to pancreatic disease research; led by Drs. David Dreiling and Henry Janowitz.

1951 – 70 Years Ago

St. Luke’s Hospital Board of Trustees welcomes its first women members: Mrs. F. Huntington Babcock (Dorothy Doubleday Babcock) and Mrs. William Gage Brady, Jr.

1956 – 65 Years Ago

Hugh Fitzpatrick, MD, performs the first open heart repair of a septal defect in New York City at St. Luke’s Hospital.

2001 – 20 Years Ago

The Beth Israel Multimedia Resources Training Center opens. It is a joint project of 1199 SEIU and BI’s Department of Training and Organizational Development to train 1199 members in basic computer skills.

Jan 29, 2021

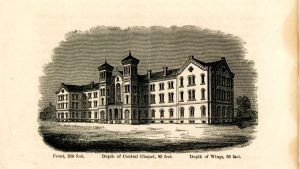

On St. Luke’s Day, October 18, 1846, the Rev William A. Muhlenberg announced to his congregation the of the Church of the Holy Communion that he believed they should established a church-related hospital in New York City to help support the poor in the community. He proposed that half of that morning’s collection be the first donation towards the goal of building such a hospital. Muhlenberg described the future hospital as a “Hotel Dieu,” – God’s Hotel, ‘a large hotel full of sick guests,’ or a “Christian family entertaining their guests, all of whom were sick.” After twelve years, and much fundraising, the doors to St. Luke’s Hospital opened to care for the sick poor of the City.

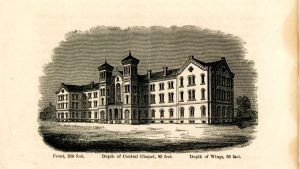

St. Luke’s Hospital’s 1858 site on W. 54th St.

Likewise, Mount Sinai Morningside’s sister hospital, Mount Sinai West, formerly Roosevelt Hospital, was also established to aid the city’s sick poor. James H. Roosevelt (1800-1863), experienced a life-altering illness that left him invalid. He decided to close his legal practice, cancel his wedding plans and devote his life to living frugally, carefully managing his fortune, to “establish … a hospital for the reception and relief of sick and diseased persons and for its permanent endowments.” Under the terms of James Henry Roosevelt’s will, the hospital was to be a voluntary hospital that cared for individuals regardless of their ability to pay. The Hospital opened in 1871 on West 59th Street between Ninth and Tenth Avenues. At its opening, Roosevelt Hospital was considered one of the most modern hospitals in the country.

Roosevelt Hospital in 1871

This year, 2021, we celebrate the 175th anniversary of the founding of St. Luke’s Hospital, now called Mount Sinai Morningside, and the 150th anniversary of the opening of Roosevelt Hospital, now called Mount Sinai West. During a time of pandemic, it may not be possible to have a big bash to celebrate the contributions, sacrifices, and simple hard work completed by the staff of these two hospitals. However, we can note the dates and celebrate in small ways, and be grateful for both hospitals that have provided dedicated health care, research, and innovations in medicine over so many years of service.

Dec 7, 2020

The Emergency Medical Service (EMS) has its roots in battlefield medical care, dating back as far as ancient Greece. American emergency medical services began to take the form we recognize today during the Civil War, when plans for medical care of battlefield injuries was organized in an intentional fashion under General George B. McClellan.

The first American civilian ambulance corps formed in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1865. New York City soon followed with its first ambulance service at Bellevue and Allied Hospital, a public hospital, in 1869, under the direction of the newly appointed NYC Sanitary Superintendent, Edward Dalton, MD, a former Union Army surgeon. Private hospitals soon followed suit.

It was common when Roosevelt Hospital opened in 1871 for patients to arrive by themselves, if mobile, or to come in aided by family or friends. However, Hospital Superintendent Horatio Paine, MD, was worried and informed the Board of Trustees that

…persons injured accidentally or overcome by heat in the immediate neighborhood of the Hospital are carried by the police almost invariably, first to the police station in 47th street, and thence by ambulance, … to the Reception Hospital in 99th street … a distance of over 2 and a half miles. Persons injured or sun-struck on the very block on which this Hospital stands, have thus been carried past its doors.

Dr. Paine feared that Roosevelt Hospital would incorrectly appear as unwilling to receive or care for emergency cases at any hour. He collaborated with other hospitals and City authorities to establish ‘casualty districts’ in the City, and in September of 1877, Roosevelt Hospital established an ambulance service for emergency care and, along with St. Luke’s, New York, and Bellevue Hospitals, provided coverage over one of the casualty districts mapped out by the City.

Horse-drawn carts were the norm from the start of Roosevelt’s service until 1900. Equipment for each of the two ambulance carts may have included tourniquets, sponges, bandages, splints, blankets, and if called for, a straitjacket. This kit was stored under the driver’s seat, along with a quart of whiskey or brandy, which was used as pain relief at that time. At first, the ambulance deployed with only a driver, but it soon became clear that an on-board physician to assess a patient’s condition and perhaps administer treatment while on route to the hospital was necessary. House staff were the first assigned to this service, in rotation. Later on a team of ‘ambulance surgeons’ was formed as a regular unit under the surgical service.

Horse-drawn carts were the norm from the start of Roosevelt’s service until 1900. Equipment for each of the two ambulance carts may have included tourniquets, sponges, bandages, splints, blankets, and if called for, a straitjacket. This kit was stored under the driver’s seat, along with a quart of whiskey or brandy, which was used as pain relief at that time. At first, the ambulance deployed with only a driver, but it soon became clear that an on-board physician to assess a patient’s condition and perhaps administer treatment while on route to the hospital was necessary. House staff were the first assigned to this service, in rotation. Later on a team of ‘ambulance surgeons’ was formed as a regular unit under the surgical service.

Ambulance service gained acceptance over time, as hospitals began to be seen as a safe place to go, a place for healing. For the year 1883, the hospital answered over 734 calls and spent $1,714.11 on feed, straw, repairs, harnesses, horseshoeing, telegraph service, purchase of horses, and also for legal expenses for accidents. That year the service also spent $1,310.92 on whiskey, wine, ale, porter, beer, and mineral waters! By its tenth year of service, ambulance calls rose to 1,122. By its twentieth year of service in 1897, total calls more than doubled the number at 3,300.

The Hospital annual report for 1899 notes that a new accident building opened with a ground floor emergency room and an ambulance court, placing more emphasis on emergency services overall. Accordingly, the service expanded to three ambulances and drivers, answering 4,041 calls.

By 1900 the horse-drawn ambulance was replaced by electric cars, which weigh 4,800 pounds and traveled at up to sixteen miles an hour. Costing $3,000.00 each, the Hospital received two as gifts – one of which was from a prominent physician of the city. The vehicles were seven feet, six inches long on the inside, eighteen inches longer than most ambulances, and had room for three reclining patients, or eight patients if they sat up. The cars were battery powered. The batteries were in a box suspended from the body of the vehicle, to be recharged each time the car returned to the Hospital. In an emergency, an extra set of batteries came with the car and could be put into place in two minutes. The batteries ran 25 miles on one charge.

Service costs ran between $3,000 and $4,000 for each vehicle in 1901 and 1902, in addition to the cost of re-fitting the necessary mechanical arrangements to store them in the old horse stables on the hospital grounds. Costs to run the service rose to $6,000 in 1903, when Hospital administrators decided to discontinue the electric cars, and return to the cheaper and more dependable horse-drawn carts.

On March 1, 1909 the ambulance service was completely discontinued, again, citing the high operational costs, partly due to the legal costs of frequent accidents. New York, Flower, and J. Hood Wright Hospitals stepped in to cover the area left without service.

That same year the State Charities Aid Association published a bill to create a Board of Ambulances – a central control agency over ambulance service in the City. Called The Newcomb-Hoey Bill, it suggested that such a Board consist of the Commissioner of Police, the Commissioner of Public Charities, and the President of the Trustees of Bellevue and Allied Hospitals. Such a Board would cover service over Manhattan and the Bronx. A sister agency, run by the Commissioner of Public Charities, would have control over Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island.

Each Board would have general control over and establish the rules and regulations governing all ambulance service in their districts, except those maintained by the Board of Health. It would establish casualty districts, and be the central clearinghouse to receive and distribute ambulance calls to the various hospital units.

The late 1930s was a time of self-assessment and re-evaluation for Roosevelt Hospital. The Hospital was nearly 70 years old and the facilities needed renovation, updating, and expansion to meet the growth of the neighborhood it served. Part of this renewal was the reintroduction of the ambulance service.

On July 5, 1939, at noon, Roosevelt Hospital resumed its ambulance service with modern motor vehicles. Two new ambulances, painted dark gray and white, cost $3,000 each. The Department of Hospitals and the Hospital shared the cost of the service’s operation. Ambulance drivers received extensive training in first aid, especially in dealing with fractures, because World War I had depleted the medical staff and a physician couldn’t be spared. The 1939 Hospital annual report lists five doctors appointed as ambulance surgeons, but they did not ride with the car unless requested by the police officer calling for it.

Prior to its discontinuation in 1909, Roosevelt Hospital’s ambulance answered calls from West 27th Street to West 86st Street and from the Hudson River to Sixth Avenue, including Central Park below 86th Street. When the service resumed in July of 1939, its area covered West 39th to West 72nd Streets between Fifth Avenue and the Hudson, including all of Central Park south of 86th Street.

In the mid-1940s the eastern border of its service was moved to the west side of Park Avenue, except for the area around Grand Central Station, which was served by Grand Central Hospital, and then again to the west side of Lexington Avenue. At this point, Roosevelt Hospital covered the largest casualty district in the City.

Emergency Department renovations in 1961, along with the closing of Grand Central Hospital that same year, forced the expansion of the ambulance district by 130 additional city blocks. The Hospital now covered midtown Manhattan from the Hudson to the East River between East 42nd Street and East 79th Street. Lenox Hill Hospital resumed its ambulance service in 1965, allowing Roosevelt Hospital to reduce its northern border from East 79th Street to East 59th Street and its eastern border returned to the west side of Fifth Avenue.

By 1946 World War II was over and New York City’s population was growing again. The ambulance service was in high demand with 9,166 calls for the year, causing the Hospital to add two additional ambulance cars to the service. The increase in demand put stress on the Accident Ward facilities, which opened in 1899. The following year, demand was even higher with 10,685 calls and 39,329 emergency cases.

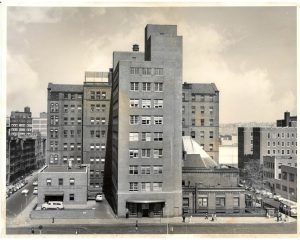

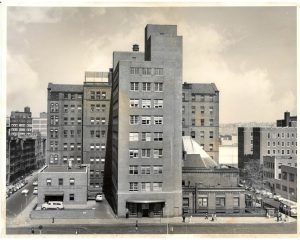

In 1947 friends of Dr. James I. Russell, a beloved and distinguished Roosevelt surgeon who had died in 1944, together with other friends of the Hospital, raised funds to construct a building to house modern accident and emergency facilities and a new surgical ward. Named the James I. Russell Memorial Building, the building featured a new, enlarged ambulance bay off 9th Avenue. The first floor handled emergency cases and the second floor was devoted to operating and treatment rooms for 46 surgical patients, and included X-Ray facilities, a plaster room, and eight observation rooms. The Hospital broke ground for the new building in August of 1948 and it opened in June of 1949.

The 1950s saw a continued expansion of the ambulance service and the upgrading and specializing of ambulance car models. In September 1956, three ambulances of a new design, made especially for metropolitan service by the Hospital Ambulance and Purchasing Department personnel, went into service. Their uniquely designed square bodies afforded room to carry four patients on stretchers, in double-decker fashion, or eight persons seated. Peter B. Terenzio, President and Director of the Hospital said the new design provided a ”functionally safe mobile unit which will permit more efficient patient care.” The new two-tone light gray ambulances were the gift of the J.P. Stevens Company, a textile concern, and the Theodore Luce Foundation.

In 1968 the Chief of Ambulance Services designed a new ambulance, for the Hospital. This ambulance, paid for with funds raised by the Hospital’s volunteer corps through the Generosity Thrift Shop, contained many life-saving devices, including an apparatus that provides vital anti-shock treatment while the vehicle is enroute from accident to Hospital.

By the 1960s automobiles were the standard mode of transportation, utilizing a growing system of roadways around the city as well as across the country. The increase in traffic provided an additional challenge to public health and safety. This problem was brought to national attention when President John F. Kennedy noted that, “Traffic accidents constitute one of the greatest, perhaps the greatest, of the nation’s public health problems.” In 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared that traffic accidents were, “…the neglected disease of modern society.”

In 1970 the National Highway Traffic Safety Act was adopted. Amongst several things, the Act standardized EMS training and urged the adoption of a single emergency number countrywide. Use of the 911 emergency number began in 1968, but was slow in gaining acceptance by every state. In 1973 the Federal EMS Systems Act was established, forming 300 EMS systems across the country, including NYC EMS, and the beginning of sweeping changes in EMS care and development across the country.

In the 1970s to 1990s, NYC’s EMS operated under the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, which dispatched both its own ambulances and hospital-owned ambulances. On March 17, 1996, NYC EMS merged with the Fire Department of New York (FDNY), forming the Bureau of Emergency Medical Services. FDNY EMS now controls the operation of all ambulances in the NYC 911 system, 70% of which are FDNY-based and 30% hospital-based, supplemented by private ambulance services.

However, the Managers soon realized a need they had overlooked: the number of sick children needing treatment. The 1860 annual report notes that one of the smaller rooms was set up as a Children’s Hall, to separate youngsters from the adults, which makes sense, as they probably needed more attention from the nursing staff.

However, the Managers soon realized a need they had overlooked: the number of sick children needing treatment. The 1860 annual report notes that one of the smaller rooms was set up as a Children’s Hall, to separate youngsters from the adults, which makes sense, as they probably needed more attention from the nursing staff.

Horse-drawn carts were the norm from the start of Roosevelt’s service until 1900. Equipment for each of the two ambulance carts may have included tourniquets, sponges, bandages, splints, blankets, and if called for, a straitjacket. This kit was stored under the driver’s seat, along with a quart of whiskey or brandy, which was used as pain relief at that time. At first, the ambulance deployed with only a driver, but it soon became clear that an on-board physician to assess a patient’s condition and perhaps administer treatment while on route to the hospital was necessary. House staff were the first assigned to this service, in rotation. Later on a team of ‘ambulance surgeons’ was formed as a regular unit under the surgical service.

Horse-drawn carts were the norm from the start of Roosevelt’s service until 1900. Equipment for each of the two ambulance carts may have included tourniquets, sponges, bandages, splints, blankets, and if called for, a straitjacket. This kit was stored under the driver’s seat, along with a quart of whiskey or brandy, which was used as pain relief at that time. At first, the ambulance deployed with only a driver, but it soon became clear that an on-board physician to assess a patient’s condition and perhaps administer treatment while on route to the hospital was necessary. House staff were the first assigned to this service, in rotation. Later on a team of ‘ambulance surgeons’ was formed as a regular unit under the surgical service.