Jun 11, 2020

This is a continuation of a guest blog post by Colleen Stapleton. Colleen is a Patient Navigator with the Liver Education and Action Program (LEAP) at Mount Sinai, where she works to improve linkage to care for patients living with Hepatitis C. You can read the original post here.

Scanning

My first day scanning, the team and I addressed the technology involved in making our Mount Sinai News collection available online. I learned about the scanning specifications to best archive our newsletters digitally. These specifications included 300 dpi (dots per inch), “do not scale,” and others particular to our scanner.

I also learned how to navigate the interesting physical space of the IT office, where the scanner was placed in a small kitchenette. Since I was scanning during lunchtime, I saw a few lunches popped in and out of the microwave. I learned that I could go ahead and put the precious paper newsletters on a non-descript plastic yellow barrel drum object, but under no circumstances should papers be placed on the potentially wet nearby water cooler!

Starting with November of 1958, I began electronically piecing together our carefully preserved collection of Mount Sinai Hospital history.

Folding Paper

Gently unfolding each 60-odd year old newsprint was both a physical challenge and delight. I soon fell into the rhythm of scanning the first page, then the second, then switching to scanning the inserted third and fourth pages. Since the newsletters are not stapled, in total I would carefully reverse the seams of two folded pages, then finish up with the back section of the first folded page.

After a few sessions, I noticed that the newsletters were getting considerably longer – some included 12 pages! This 12-page spread would include a total of three seams, and so unfolding and folding would come to resemble the act of taking apart and putting back together a precious Russian doll.

Troubleshooting

My first day at the scanner I became aware that any file containing more than five pages could not be sent via email to our Archives team account. I made the decision at this time to scan four pages at a time, sending the files to the Archives account in pieces. I soon saw the stacks of newsletters flowing from the “un-scanned” to the “scanned” pile.

After each session I would return to my desk and make sure every issue was represented and the scan quality was good. The various parts of each issue were then virtually ‘stitched’ together. Though some months came and went without Mount Sinai Hospital News editions, each newsletter is marked chronologically with issue numbers.

The first Science News insert of the new Mount Sinai School of Medicine

One of my favorite developments in my scanning came with the advent of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Science News, an insert that was developed as the medical school was founded and produced more and more significant scientific discoveries. There was also the Mount Sinai Medical Center News title change in November-December 1969 to correspond with the newly built school of medicine. The history of Mount Sinai was expanding before my eyes and I had to ensure my metadata reflected these changes!

Moving Forward with Metadata

After scanning part I of the MSH News archive, the team met with the Aufses Archives’ Digital Archivist to clarify our strategy moving forward. We confirmed our goal of making the Adobe PDFs of the News pages available online, creating a digital index of all MSH News electronic files, as well as providing readers with a search function powered by Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to more easily search the newsletter files.

We identified questions to the tune of “How should we put the PDF files online?” and “how can we most easily create an index to the publication?” We ultimately decided to OCR the PDF documents with Adobe and then dump the words into a database program used by the Aufses Archives called DBTextworks. We started with a few pilot issue files and we identified any necessary metadata fields for our project.

So began an exciting new phase: cleaning and inputting metadata. Unfortunately, this was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to stay home, and we have not been able to continue the scanning. However, the work continues with the efforts of a fantastic new summer intern working remotely — soon all of the scanned issues will be described and searchable.

Stay tuned for more blog installments exploring this digitization project along with coverage of the many unique historical Sinai snapshots found in the MSH News!

Jun 4, 2020

An update to this blog post can be found here.

Founded in 1892, the early history of Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital was decorated with a series of success stories in the treatment of disease. Against the background of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, then affected by poverty, close living quarters, and dangerous working conditions, its residents, largely recent Jewish immigrants, were made vulnerable to many of the contagious diseases of that era. In its first years, Beth Israel contributed research to combat the typhoid epidemic of 1906-1907, established an after-care clinic to children affected by the 1916 polio epidemic, and is credited with finding the cure for trachoma, which had previously been a cause to turn away new immigrants at Ellis Island.

Only twenty-five years after Beth Israel’s opening, the United States was embroiled in the first World War. The Hospital encouraged its medical staff to join the Medical Reserve Corps, with approximately half of its doctors signing up. The Hospital had also encouraged its nurses, physicians and other staff to join the war effort.

This left Beth Israel in a precarious position when the 1918 Influenza epidemic reached New York City. Being chronically understaffed, Beth Israel’s Medical Board contacted the Department of Health for advice. The response was simply: “There is nothing to advise except the use of gauze masks which did not always prevent the disease.” In November 1918, the Hospital eliminated visiting hours, curtailed teaching hours, and turned the Male Medical Ward over to the Department of Health to use as an isolation facility for the pandemic. (The DOH never used the facility because they were similarly understaffed.)

Female ward of Beth Israel Hospital, Jefferson and Cherry Street, circa 1910

Ultimately, Beth Israel was only able to admit twenty-nine influenza patients. (Update: This number is disputed in other sources.) Seven members of the House Staff were awarded $25 (approximately $500 today) for “self-sacrificing services performed” and the Hospital offered special incentive pay to doctors and nurses to help combat the fact that they were understaffed.

Despite the limited patient intake, Beth Israel’s contributions to the 1918 flu pandemic were still impactful. In December 1918, Superintendent of the Hospital, Louis J. Frank, contacted Presidents Roosevelt and Taft to encourage universal nursing training in the education of women, likely in response to the chronic under-staffing at this time. By January 1919, many of the patients in the Hospital were admitted for “post-influenzal complications” leading to the care of many affected by the pandemic.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

May 28, 2020

Mount Sinai physicians have a long tradition of making important contributions to the scientific literature. A good example is the following case from the 1910s, when typhus swept the world, killing thousands of people.

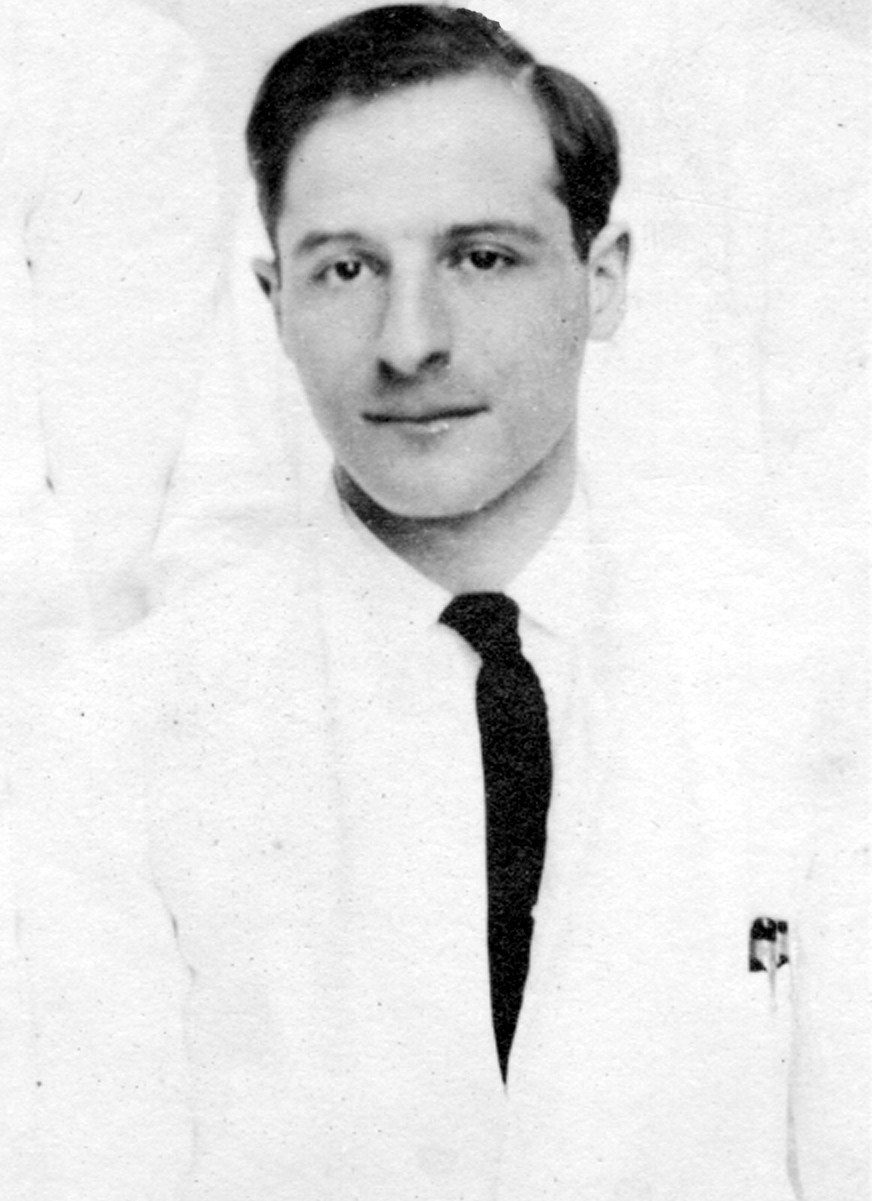

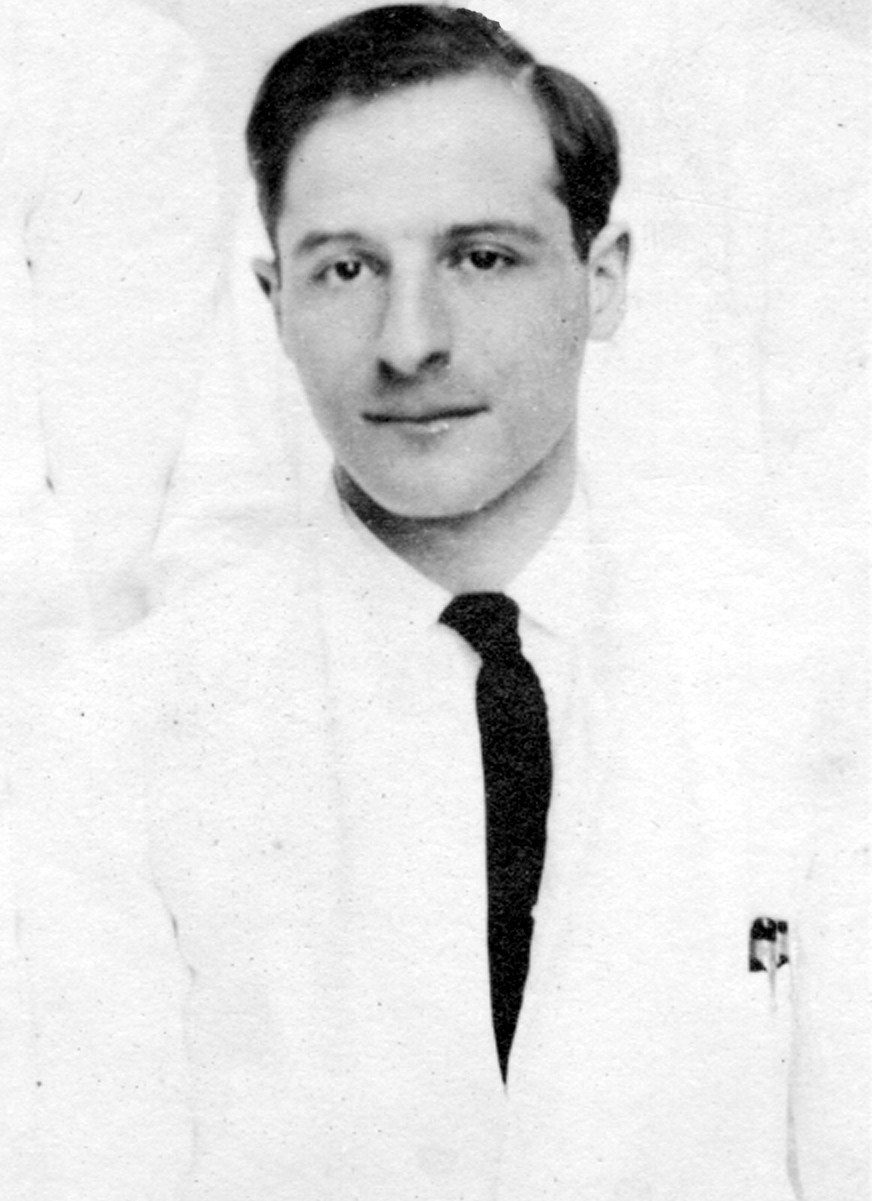

In 1910, Nathan Brill, MD, a doctor in the Department of Medicine, published a description of what he thought was the endemic form of typhus; this became known as Brill’s Disease. (Later Hans Zinsser showed that it was not endemic, but a mild recrudescent form of epidemic typhus and the name was changed to Brill-Zinsser disease.) In 1913, Harry Plotz, MD, an intern working in Mount Sinai‘s Pathology Laboratory, believed that he had discovered an organism that caused typhus. He published a Letter in JAMA in 1914 outlining his research.

Harry Plotz, MD as a Mount Sinai intern in 1915

Since this was such an important public health problem, in 1915, Mount Sinai’s Trustees took the unusual step of agreeing to fund a trip to gather blood specimens in the Balkans, where there was a typhus outbreak – and the early stages of World War I. As noted in Wikipedia: “disease ravaged the armies of the Eastern Front, where over 150,000 died in Serbia alone. Fatalities were generally between 10% and 40% of those infected and the disease was a major cause of death for those nursing the sick.”

The research results of this trip were described by the physicians Harry Plotz and George Baehr in a 1917 paper in the Journal of Infectious Diseases. The details of the trip itself are described in the 1916 Annual Report of The Mount Sinai Hospital This narrative also describes an additional trip by Dr. Peter Olitzky to Mexico, also funded by Mount Sinai, when the researchers in Europe were taken prisoner by the Austro-Hungarian government. This lengthy quote provides the Trustee President of Mount Sinai’s description of the events of 1915-16:

In pursuance of my remarks of last year in regard to the typhus expedition to Serbia, I wish to state that Drs. George Baehr and Harry Plotz after many difficulties established a laboratory at Belgrade in a hospital directed by the American Red Cross. Thirty-six hours before the bombardment of Belgrade, they left for Uskub and there set up a laboratory in the Lady Paget Hospital, and shortly thereafter the town was occupied by the Bulgarians. Very soon afterwards they were invited by the Bulgarian and Austrian Governments to work under their auspices. They then left for Sofia and afterwards went to Vienna, Lemberg and into Russia….

Because of the fact that Drs. Baehr and Plotz during the first six months of their stay in Europe, practically did not come in contact with typhus fever, it was considered important to send a second expedition into Mexico to determine the cause of the Mexican typhus fever, and to carry on other work which at that time we were not sure could be carried on in Europe. The second expedition consisted of Drs. Peter K. Olitzky and Bernard S. Denzer, accompanied by Mr. Irving Brout, a laboratory helper, and the expedition was under the guidance and care of Dr. Carlos E. Husk, a prominent surgeon attached to the staff of the American Smelting & Refining Co. The expenses of the expedition were defrayed in part by Trustees of the Mount Sinai Hospital and in part by the American Smelting & Refining Co.

It was first decided to go to Aguascalientes, but after the expedition reached Matehuala it was determined to remain there, as even at that distance from the border the danger, because of dis- turbances of international conditions, was very great. Early in March, because of the increasing danger in which the men were placed, they were requested to return. The members of the expedition did not, however, leave, because Dr. Olitzky had been stricken with a severe attack of typhus fever. Very shortly thereafter, the plants of the American Smelting & Refining Co. throughout Mexico were closed down, and Dr. Olitzky had to be removed to Laredo, Texas. Just before the departure Dr. Husk, who had been of the greatest aid in the accomplishment of a remarkable piece of work within four weeks, also fell ill of typhus fever, and was brought into Laredo in a very serious condition. Dr. Olitzky after going through a most dangerous attack of the disease, recovered, but unfortunately it proved impossible to save Dr. Husk’s life.

During the course of this expedition the same germ was found in the typhus fever cases in Mexico as had been found in New York and as was found by the members of the European expedition in Serbia, Bulgaria, Austria and Russia. Apart from that, the typhus germ was cultivated repeatedly from lice, which have in recent years been considered the agent in transferring typhus fever from one person to another. Some further scientific studies were made, and vaccination done on a rather large scale. The results of the vaccination cannot be determined at the present time because of the unsettled conditions in Mexico.

In the end, no successful vaccine has been developed for typhus, but antibiotics and public health measures have made it a treatable, rarely fatal disease in the U.S.

The story of typhus and Mount Sinai is important because it shows the institution’s commitment to research and developing new treatments during times of crisis. As shown here, this commitment is not solely from the medical and scientific staff, but also from the Trustees and supporters of Mount Sinai. When times are dire, as in today’s COVID-19 pandemic, Sinai finds a way to enable the work to get done to advance medical knowledge and improve the treatment of patients.

May 12, 2020

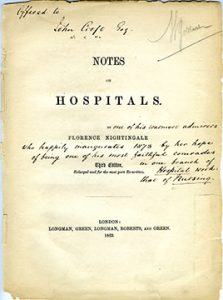

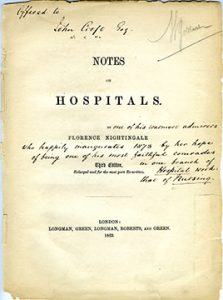

This year the world marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Florence Nightingale (1820-1910.) Her name is known around the world and nurses everywhere enjoy the fruits of her labors today. She lived a long time ago in a very different world, but she enunciated the basic philosophy of modern nursing, and introduced statistics into the study of disease.

The Aufses Archives has copies of two of Miss Nightingale’s books: Notes on Nursing and Notes on Hospitals. The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing, which existed from 1881-1971, had a small collection of Nightingale letters that they had gathered over the years. Some of these were given to the Columbia University School of Nursing in 1953, as shown in the image below.

From the Aufses Archives

Hospitals, schools of nursing, archives, and history of medicine collections will be marking the 200th anniversary of Florence Nightingale this year with celebrations, blog posts, exhibits and lectures. Here are links to just a few of those celebrations going on this year:

Nightingale: Lady and Legend at the National Library of Medicine: https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2020/05/12/nightingale-lady-and-legend/ This includes this note on sources: The National Library of Medicine’s holdings of Nightingale materials are (unsurprisingly) extensive, with over seventy printed titles and editions. In addition, the Library holds a group of Nightingale letters written between 1845 and 1878, all of which may be read as part of the Florence Nightingale Digitization Project, and a copy of an oral history interview conducted by M. Adelaide Nutting (herself a giant in the history of nursing) in 1890. A transcript is available at http://oculus.nlm.nih.gov/2935116r.

A blog post on the University of Maryland, Baltimore School of Nursing ties to Nightingale: https://www2.hshsl.umaryland.edu/hslupdates/?p=4177

A blog post at the UCLA Library about the Elmer Belt FN Collection and other Nightingaleiana we have and use: https://www.library.ucla.edu/blog/special/2020/05/11/happy-birthday-florence-nightingale

Finally, there is a special exhibit at the Florence Nightingale Museum in London called Nightingale in 200 Objects, People & Places https://www.florence-nightingale.co.uk/200objects/ Sadly, the Museum is closed due to the pandemic and is struggling financially. As they note:

Nursing, washing your hands and evidence based-healthcare, pioneered by Florence Nightingale, have become more important than ever before and we’re calling upon our friends and supporters to help us preserve her story and legacy.

Apr 10, 2020

This is a guest blog post by Colleen Stapleton. Colleen is a Patient Navigator with the Liver Education and Action Program (LEAP) at Mount Sinai, where she works to improve linkage to care for patients living with Hepatitis C. Colleen is an advocate for innovative health literacy strategies and a volunteer with the the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, where she hopes to complete a history project mapping women’s contributions to the hospital.

Inspiration

Every Tuesday and Thursday before the global shutdown due to SARS-CoV-2, I left my office on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and walked a few blocks down to the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the Annenberg Building on 5th Ave. The building, part of Mount Sinai Health System’s main hospital complex, is a labyrinth of offices and meeting spaces. On the 10th floor, next to IT offices and tucked behind the Otolaryngology suite, is the office of the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives.

I started volunteering with the archives as a way to keep in touch with my personal interests while working as a patient navigator on a public health project in the Mount Sinai Hospital Liver department. My interest in medical devices, most notably the Dalkon Shield IUD tragedy, had introduced me to historian Susan Perry’s fantastic project that took shape in her 1985 book Nightmare.

Perry’s work inspired me to scheme: how could I sharpen my historical eye? How could I hone my training in visual history and explore my personal investment in the stories of women in medicine? What I found in my project scanning and cataloguing Mount Sinai Health System newsletters, however, was much more upbeat than the project that had originally inspired me.

When I reached out to Mount Sinai’s archive I was generously invited to join a team dedicated to preserving the accomplishments of Mount Sinai providers, scientists, and workers. My lunch-hour task would be to make the Archives’ collection of newsletters more accessible to our archivists, and if possible the Archives’ online readership.

Collection

The first issue of The Mount Sinai Hospital News, which ran from 1958-1982

The Aufses Archives has many collections of newsletters. I am starting with the “Mount Sinai Hospital News.” The series consists of several large folders containing two sets of the title. The first newsletter set, set “one”, is known as the “preservation set.” As such, it isn’t handled frequently and contains the best copies. Set “two” contains the copies of the newsletter that are meant to be handled. This handling may occur when inquiries come in from several sources, including relatives of nursing school alumnae, providers previously employed by the hospital or medical school, and hospital or school departments sourcing historical projects, among others. Both sets are stored among the other contents preserved by the Archives.

The archives are not a museum, and so they contain mostly paper-based items and files pertaining to the history of the hospital and medical school. In addition to the collection of newsletters, the Archives includes photographs, meeting minutes, office files, and miscellanea. The collection does house selected objects, including some medical devices, dolls, and even a moulage kit from the 1990s recently passed along to the Emergency Department for use in emergency drills. One of the oldest objects, a ledger indicating notes from one of the first Mount Sinai Beth Israel board meetings, is written by hand in Yiddish and dates back to the 1890s.

The Plan

At the start of the project, the team discussed plans for indexing a collection of newsletters. Would we keep an Excel file of key terms, titles, and dates? Could we also digitize the newsletters? After thinking about the “what” that we would like to make available, we discussed the “how” and “why” of the project. How would the Archives’ online readership access tools to search the newsletter collection? Would we be able to leverage resources to make every issue available online? What were the costs and benefits of spending time uploading each issue digitally?

I was happy to volunteer my help with scanning the newsletters, due in part to my history with an old archive project at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, NY. As a curatorial intern I had been dying to scan the museum’s collection of newspaper clippings highlighting exhibitions and visits by Yoko Ono and John Lennon among other fascinating historical happenings! As it happened, our crew in Syracuse was limited by resource shortages, and scanning would have to be pushed to the next summer.

After some thought and research into searchable PDF text formats, my inclination to scan and upload every issue into our database (then online) was accepted! I was carefully handed a small pile of newsletters, then headed into our neighboring IT office to commandeer the scanner for an hour. The process of scanning had begun!

Watch for Part II, coming soon.

Nov 26, 2019

November is an important month in the life of Mount Sinai West. The Hospital’s founder, James H. Roosevelt, was both born on the 10th in 1800 and died on the 30th in 1864. Additionally, the Hospital’s doors opened on the 2nd in 1871. And in November 1964, the then Roosevelt Hospital inaugurated its first Obstetrical Service. Prior to this such a service was deemed unnecessary as its neighbors included the Sloane Hospital for Women and the Nursery & Child’s Hospital. However, in 1928, Sloane moved uptown to join the new Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center and in 1934, Nursery & Child’s merged with New York Hospital, leaving an obstetrical service vacuum on the west side of Manhattan.

November is an important month in the life of Mount Sinai West. The Hospital’s founder, James H. Roosevelt, was both born on the 10th in 1800 and died on the 30th in 1864. Additionally, the Hospital’s doors opened on the 2nd in 1871. And in November 1964, the then Roosevelt Hospital inaugurated its first Obstetrical Service. Prior to this such a service was deemed unnecessary as its neighbors included the Sloane Hospital for Women and the Nursery & Child’s Hospital. However, in 1928, Sloane moved uptown to join the new Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center and in 1934, Nursery & Child’s merged with New York Hospital, leaving an obstetrical service vacuum on the west side of Manhattan.

Hints of change started in July 1955 when Roosevelt Hospital’s President of the Board of Trustees, Garrard B. Winston, died and bequeathed nearly $4 million to the hospital. The Trustees decided to use the bequest to fund a much needed new building that would be named after Winston to honor his dedication to the Hospital. The construction of the building began in 1958, after demolition of the original Administration Building was complete.

In October of 1958, The Ambrose Monell Foundation presented the Hospital with a gift of one million dollars to construct an obstetrical floor and establish a much needed Obstetrical Service. The gift was arranged through Board member Edmund C. Monell, as a memorial to his mother, the late Maude Monell Vetlesen, who served as an honorary member of the Board of Trustees from March 1956 until her death in May of 1958. Mrs. Vetlesen also had a particular interest in obstetrical care. Occasionally its place in the training of physicians and nurses was the topic of conversation between her and several hospital professionals with whom she had an acquaintance. The floor would be called The Maude Monell Vetlesen Maternity Pavilion.

In 1961 the cornerstone was laid for the 12-story Garrard Winston Memorial Building. At the end of that year, Dr. Ralph W. Gause was appointed the first Chief of the Obstetrical Department. He began the process of building the department so it would be ready for full time operation when the Winston Building was opened.

The Winston Building opened in September of 1964, and the Obstetrical Department was inaugurated in November of that year. When in full operation, the OB Department expected to care for about 125 deliveries a month, and included antepartum and postpartum clinics. The first birth, a boy named Daniel Winston Maurer, took place on November 17th, and was celebrated with the gift of an engraved silver cup, as was the first girl’s birth when Doreen Ann Dichiora was born a few days later. There were 20 more deliveries by the end of that year. In 1965, the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology completed its first full year with a record total of 1,004 gynecological operations and 597 deliveries.

Oct 14, 2019

Thirty-five years ago, on October 3, 1984, the Beth Israel Hospital School of Nursing was renamed and dedicated as the Phillips Beth Israel School of Nursing, in honor of Seymour Phillips. Mr. Phillips (1903-1987) served as chairman of the School of Nursing Board for almost 40 years. He watched over the School through a myriad of changes, in nursing, in Beth Israel, and the world. He also was a tremendous supporter of the Hospital itself, in particular supporting cardiac care and surgery. Mr. Phillips was the grandson of the founder of Phillips-Van Heusen Corporation and actively worked at the company from 1924-1967.

Seymour Phillips greeting members of the Beth Israel Class of 1968

Serving Beth Israel was a Phillips family tradition that stretched before Seymour Phillips and after him as well. Their name continues to be associated through the Phillips Ambulatory Care Center, the Phillips Family Practice, the Phillips Health Sciences Library and, of course, the Phillips Beth Israel School of Nursing.

As noted in the centennial history of the School of Nursing:

At every school of nursing graduation, Seymour Phillips stood at the podium and gave a rousing, inspiring speech for the graduates. He would turn his back to the audience and directly address the new nurses seated on the stage, as if no one else was in the auditorium. The students did not need to be told how much Phillips cared for them. His actions spoke louder than his eloquent words.

When Seymour Phillips died on 1987, Rose Muscatine Hauer, [then] Dean Emeritus…was one of the speakers at the service at Temple Emmanuel…. Hauer stepped to the podium to address the audience. As she looked up to speak, 200 nursing students in uniform – their starched white caps at attention – rose from their seats to honor their dear friend and long-time patron.

Apr 30, 2019

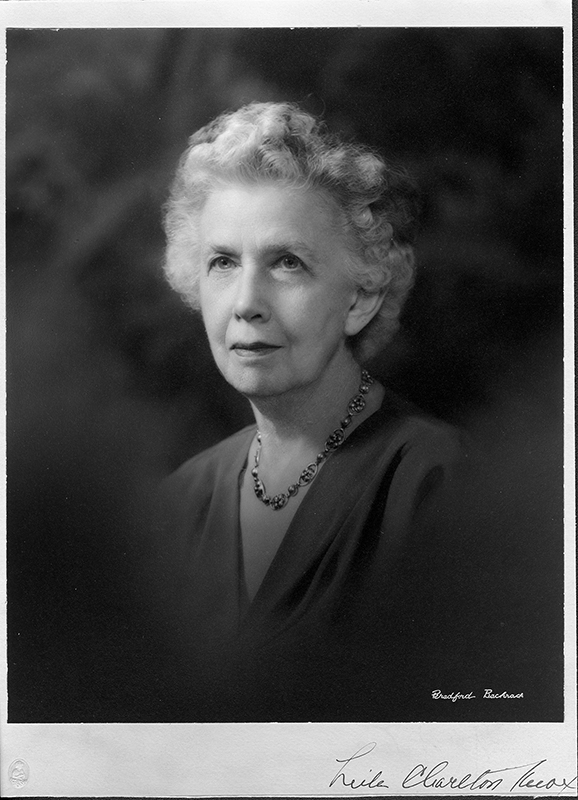

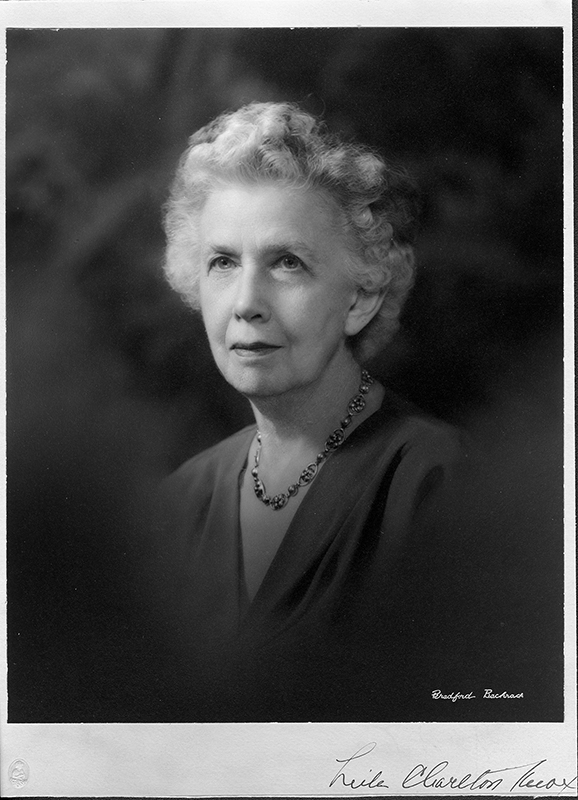

March is Woman’s History month and there are many notable women from within the MSSL fold to honor, but Dr. Leila C. Knox is the first notable woman I would like to highlight for Women’s History Month. Dr. Knox was the first woman to be hired as an Attending Physician on any level at St. Luke’s Hospital. Leila Knox, BA started at St. Luke’s in 1913 as an assistant and bacteriologist to Resident Pathologist Dr. J. Gardiner Hopkins. At that time, it wasn’t uncommon for educated women to work in the Pathology Labs. But long-time Director of Pathology, Dr. Francis C. Wood knew Knox wanted more out of her work and encouraged her to attend medical school. She enrolled in Cornell University Medical College. She became the Resident Pathologist at St. Luke’s in 1917, and in 1918 she added ‘MD’ to that title. Working together, she and Dr. Wood developed a surgical pathology lab of importance and value, and one which was notable in its field. She was appointed Assistant Attending Physician in 1923, a title which was unique at that time. Knox wasn’t restricted to laboratory work, but trained technicians and members of the House Staff, conducted autopsies, and made rounds as an Attending to observe patients. She published many papers generated by her efforts both as an Attending and a Pathologist, and was Assistant Editor of the American Journal of Cancer from 1930-1938, writing abstracts and original articles for the publication. She was recognized abroad and at home for her work as a tissue diagnostician. She retired in 1948 after thirty years of service, holding the title of Pathologist, Director of Laboratories and Associate Attending Physician.

March is Woman’s History month and there are many notable women from within the MSSL fold to honor, but Dr. Leila C. Knox is the first notable woman I would like to highlight for Women’s History Month. Dr. Knox was the first woman to be hired as an Attending Physician on any level at St. Luke’s Hospital. Leila Knox, BA started at St. Luke’s in 1913 as an assistant and bacteriologist to Resident Pathologist Dr. J. Gardiner Hopkins. At that time, it wasn’t uncommon for educated women to work in the Pathology Labs. But long-time Director of Pathology, Dr. Francis C. Wood knew Knox wanted more out of her work and encouraged her to attend medical school. She enrolled in Cornell University Medical College. She became the Resident Pathologist at St. Luke’s in 1917, and in 1918 she added ‘MD’ to that title. Working together, she and Dr. Wood developed a surgical pathology lab of importance and value, and one which was notable in its field. She was appointed Assistant Attending Physician in 1923, a title which was unique at that time. Knox wasn’t restricted to laboratory work, but trained technicians and members of the House Staff, conducted autopsies, and made rounds as an Attending to observe patients. She published many papers generated by her efforts both as an Attending and a Pathologist, and was Assistant Editor of the American Journal of Cancer from 1930-1938, writing abstracts and original articles for the publication. She was recognized abroad and at home for her work as a tissue diagnostician. She retired in 1948 after thirty years of service, holding the title of Pathologist, Director of Laboratories and Associate Attending Physician.

Apr 30, 2019

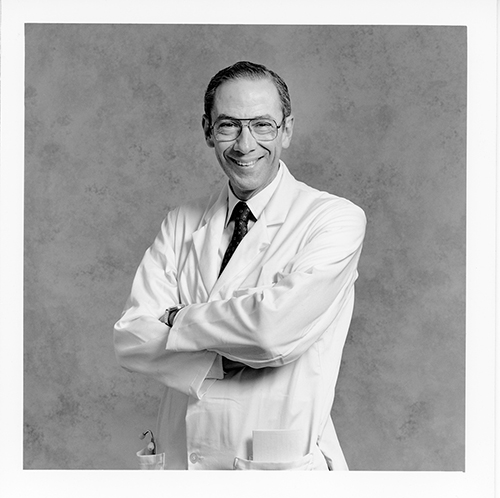

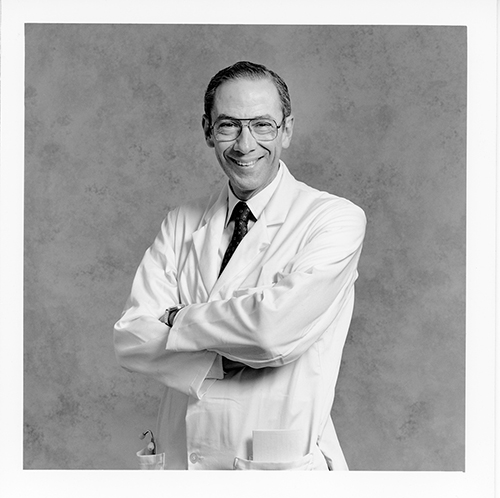

It is with great sadness that we share news of the passing of our dear friend and supporter Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD (1926-2019), one of the Mount Sinai Health System’s most respected physicians and Chairman Emeritus of The Ruth J. & Maxwell Hauser and Harriet & Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Department of Surgery at The Mount Sinai Hospital, and Professor in Surgery as well as the Department of Population Health Science and Policy.

Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD, 1926-2019

An innovative leader who served as Chair of the Department of Surgery from 1974-1996, Dr. Aufses ushered in Mount Sinai’s adoption of laparoscopic surgery and oversaw the expansion of ambulatory surgery and the hospital’s transplant program. He organized the surgical team that performed the first liver transplant in New York State in 1988.

Within Mount Sinai, Dr. Aufses served as a mentor to many residents and fellows and helped to break down barriers for women and minority surgeons. Over the years, he received many Excellence in Teaching awards from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, as well as institutional honors, including the Alumni Association’s Jacobi Medallion, and the Alexander Richman Award for Humanism in Medicine. He was the holder of Mount Sinai’s Gold Headed Cane from 1982 to 1997. On 17 occasions, medical students selected Dr. Aufses to administer the Oath of Maimonides or the Oath of Hippocrates at commencement, and on three occasions he was chosen to serve as Commencement Grand Marshal. In May 2003, Dr. Aufses delivered the medical school’s commencement address and was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters.

In addition to publishing more than 235 research papers and book chapters—many on the topics of surgical education and inflammatory bowel disease—he held leadership roles in many professional organizations. These include the New York Academy of Medicine, the American College of Gastroenterology, the New York Surgical Society, the American College of Surgeons, and the American Surgical Association.

Dr. Aufses also had a keen interest in Mount Sinai’s long and storied history, and published two books on the subject with institutional archivist Barbara Niss. This House of Noble Deeds: The Mount Sinai Hospital, 1852-2002 (New York University Press, 2002), chronicled the 150-year history of The Mount Sinai Hospital, focusing on the accomplishments of the staff since its origin as The Jews’ Hospital in the City of New York. Teaching Tomorrow’s Medicine Today: The Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 1963-2003 (New York University Press, 2005), detailed the first forty years of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

In April 2017, Dr. Aufses’ support of the Archives was made clear when the Mount Sinai Archives was formally dedicated as the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives.

The staff of the Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives will miss Dr. Aufses’ kindness, sense of humor, and selfless service to Mount Sinai. Dr. Aufses was calm and steady in the operating room and in life. He delighted in his trainees’ achievements, and set an example of honesty, integrity, and loyalty for those who followed him. He was a true Mount Sinai Giant.

Feb 27, 2019

To celebrate Black History Month, we would like to bring William Johnson Trent, Jr. (1910-1993), to your attention. Trent was the first African-American elected to the Board of Trustees of St. Luke’s Hospital. He was an active member of the Board from 1965 to 1977 and served four years as the Board’s President from 1970 – 1974. He remained a concerned Honorary Trustee from the time of his resignation until his death from cardiac arrest in November, 1993.

Trent was born in North Carolina and raised in Atlanta, Georgia. He attended a private high school and graduated from Livingstone College in 1930. He went on to earn an MBA from the Wharton School, followed by graduate work in economics at the University of Chicago. Afterwards, he returned to North Carolina and taught for two years at Livingstone College and later at Bennet College, where he was also an Acting Dean for a year.

He was the son of an early organizer of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Trent, Sr.’s civil rights activism seems to have been passed down to Trent, Jr., who served as Adviser on Negro Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes between 1939 and 1946, and played a part in desegregating national park facilities. Later he held the position of Race Relations Officer in the Federal Works Agency. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt invited Trent to be a part of an informal group of African-Americans, casually called the “Black Cabinet,” who served as public policy advisers to Roosevelt and his wife during Roosevelt’s administration.

Joining with Tuskegee Institute president Frederick D. Patterson, and educator and civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune, Trent was co-founder and Executive Director of the United Negro College Fund from its, start in 1944 until he left 1964, raising $78 million to support private black colleges and universities.

During the time Mr. Trent was on the St. Luke’s Board he was an Assistant Personnel Director, involved in training and personnel development at Time, Inc., retiring in 1975. He was also on the boards of the National Social Welfare Assembly of New York City, the African-American Institute, the New Rochelle Council for Unity, the Child Study Association of American, and Livingstone College. He served on the College Housing Advisory Committee, Housing and Home Finance Agency, the Advisory Committee on Governmental Operations for the City of New Rochelle and was on the Steering Committee of the African Scholarship Program of American Universities, Cambridge, Mass., and the Personnel Committee of International House, a Morningside Heights neighbor.

While Trent was a strong advocate for African-American causes, he had the ability to bring people of all color together to work for a worthy cause, which may have been what drew his nomination to the Board of Trustees at St. Luke’s Hospital and made him a beloved, and honored member of it.

November is an important month in the life of Mount Sinai West. The Hospital’s founder, James H. Roosevelt, was both born on the 10th in 1800 and died on the 30th in 1864. Additionally, the Hospital’s doors opened on the 2nd in 1871. And in November 1964, the then Roosevelt Hospital inaugurated its first Obstetrical Service. Prior to this such a service was deemed unnecessary as its neighbors included the Sloane Hospital for Women and the Nursery & Child’s Hospital. However, in 1928, Sloane moved uptown to join the new Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center and in 1934, Nursery & Child’s merged with New York Hospital, leaving an obstetrical service vacuum on the west side of Manhattan.

November is an important month in the life of Mount Sinai West. The Hospital’s founder, James H. Roosevelt, was both born on the 10th in 1800 and died on the 30th in 1864. Additionally, the Hospital’s doors opened on the 2nd in 1871. And in November 1964, the then Roosevelt Hospital inaugurated its first Obstetrical Service. Prior to this such a service was deemed unnecessary as its neighbors included the Sloane Hospital for Women and the Nursery & Child’s Hospital. However, in 1928, Sloane moved uptown to join the new Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center and in 1934, Nursery & Child’s merged with New York Hospital, leaving an obstetrical service vacuum on the west side of Manhattan.

March is Woman’s History month and there are many notable women from within the MSSL fold to honor, but Dr. Leila C. Knox is the first notable woman I would like to highlight for Women’s History Month. Dr. Knox was the first woman to be hired as an Attending Physician on any level at St. Luke’s Hospital. Leila Knox, BA started at St. Luke’s in 1913 as an assistant and bacteriologist to Resident Pathologist Dr. J. Gardiner Hopkins. At that time, it wasn’t uncommon for educated women to work in the Pathology Labs. But long-time Director of Pathology, Dr. Francis C. Wood knew Knox wanted more out of her work and encouraged her to attend medical school. She enrolled in Cornell University Medical College. She became the Resident Pathologist at St. Luke’s in 1917, and in 1918 she added ‘MD’ to that title. Working together, she and Dr. Wood developed a surgical pathology lab of importance and value, and one which was notable in its field. She was appointed Assistant Attending Physician in 1923, a title which was unique at that time. Knox wasn’t restricted to laboratory work, but trained technicians and members of the House Staff, conducted autopsies, and made rounds as an Attending to observe patients. She published many papers generated by her efforts both as an Attending and a Pathologist, and was Assistant Editor of the American Journal of Cancer from 1930-1938, writing abstracts and original articles for the publication. She was recognized abroad and at home for her work as a tissue diagnostician. She retired in 1948 after thirty years of service, holding the title of Pathologist, Director of Laboratories and Associate Attending Physician.

March is Woman’s History month and there are many notable women from within the MSSL fold to honor, but Dr. Leila C. Knox is the first notable woman I would like to highlight for Women’s History Month. Dr. Knox was the first woman to be hired as an Attending Physician on any level at St. Luke’s Hospital. Leila Knox, BA started at St. Luke’s in 1913 as an assistant and bacteriologist to Resident Pathologist Dr. J. Gardiner Hopkins. At that time, it wasn’t uncommon for educated women to work in the Pathology Labs. But long-time Director of Pathology, Dr. Francis C. Wood knew Knox wanted more out of her work and encouraged her to attend medical school. She enrolled in Cornell University Medical College. She became the Resident Pathologist at St. Luke’s in 1917, and in 1918 she added ‘MD’ to that title. Working together, she and Dr. Wood developed a surgical pathology lab of importance and value, and one which was notable in its field. She was appointed Assistant Attending Physician in 1923, a title which was unique at that time. Knox wasn’t restricted to laboratory work, but trained technicians and members of the House Staff, conducted autopsies, and made rounds as an Attending to observe patients. She published many papers generated by her efforts both as an Attending and a Pathologist, and was Assistant Editor of the American Journal of Cancer from 1930-1938, writing abstracts and original articles for the publication. She was recognized abroad and at home for her work as a tissue diagnostician. She retired in 1948 after thirty years of service, holding the title of Pathologist, Director of Laboratories and Associate Attending Physician.