Jan 11, 2019

On January 11, 1919, the Mount Sinai Hospital affiliated unit, U.S. Army Base Hospital No. 3 was officially relieved of duty. The war was over for them. All told, they had treated 9,127 patients with 172 deaths (54 surgical and 118 medical, the latter due mainly to pneumonia related to the influenza epidemic that swept the world in 1918). On March 5th, the doctors and nurses returned to New York City. The enlisted men returned two and a half weeks later.

A ward at Base Hospital No. 3

Jul 31, 2018

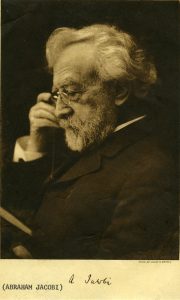

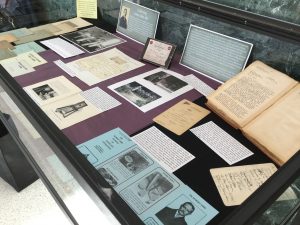

The Aufses Archives recently announced the opening of a new digital collection of letters to and from Abraham Jacobi, MD, the “father of American pediatrics” and a towering figure in the history both of Mount Sinai and of nineteenth-century American medicine. The letters, most of which deal with the staffing and administration of Mount Sinai’s outpatient clinics, contain the historical traces of many other physicians and surgeons who passed through Mount Sinai in the late nineteenth century. Some went on to quiet careers in private practice; others were famous in their time but have since been forgotten.

One letter in the collection, dated March 1st, 1879, contains an update from Rudolf Tauszky, MD, Secretary of the Medical Staff of the Out-Door Department (that is, the outpatient clinics), informing Dr. Jacobi of changing staff assignments. Among other changes to the roster, Doctors M.J. and E.J. Messemer had been appointed to the internal medicine clinic.

These forgotten names piqued our curiosity. Who were they? How were they related? Research confirmed that the Messemers were brothers and had graduated from Bellevue Hospital Medical College (predecessor of today’s NYU School of Medicine) a few years previously. At a time when the modern system of clinical instruction was still in its infancy, positions in the charity outpatient clinics of a prestigious hospital were a valuable way for recent graduates to gain practical experience on the way to establishing a private practice.

Further research revealed the subsequent career of Michael Jean Baptiste (M.J.B.) Messemer, MD. He turned out to have been a colorful figure who was a minor celebrity in old New York.

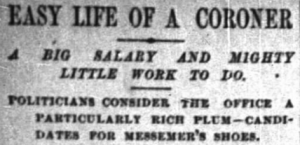

New York Times, July 21, 1890

New York Times, July 21, 1890

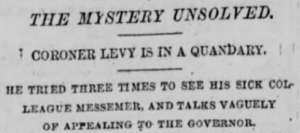

New York Tribune, May 27, 1891

New York Tribune, May 27, 1891

New York City in the late nineteenth century was limited to Manhattan and a portion of what is now the South Bronx, and city politics were firmly under the control of Tammany Hall, of which Dr. Messemer was a loyal member. Today, the Chief Medical Examiner of New York City is a highly regarded professional, but in the 1880s the position of City Coroner was considered a “plum” job for Tammany loyalists whose incumbents could draw a high salary with relatively little work. Dr. Messemer became one of the city’s four coroners in 1883. One colleague, Coroner Levy, charged Messemer with spending much of his time in recreational travel, pleading sickness rather than attending to his public duties. Levy remarked sarcastically to a New York Tribune reporter that “I am afraid that the public is skeptical about him.”

New York Times, December 10, 1885

New York Times, December 10, 1885

Dr. Messemer did investigate cases, however. Many of these were widely reported in the popular press, leading to accusations that Dr. Messemer was publicity-hungry and using the office of coroner to promote himself. In 1885, on the death of railroad magnate William Henry Vanderbilt, Messemer rushed to Vanderbilt’s mansion in the company of a reporter to inspect the body for foul play. A colleague accused him of “looking for notoriety,” adding that such an uninvited inspection was “wrong and uncalled for” under the Police Department rules governing suspicious deaths.

New York World, March 3, 1894

New York World, March 3, 1894

Dr. Messemer passed away in 1894 while traveling in Europe. The “widely known New Yorker,” wrote the obituary columnist of the New York World, “was ever willing to help his friends among newspaper men get news, and thereby get notoriety for himself. To-day Messemer furnishes another and a last story.” The will that Dr. Messemer had placed on file in New York left his entire estate to his brother, but his European mistress claimed he had written her into his will on his deathbed. Although she traveled to New York to contest the will in person, the suit was eventually settled in favor of his brother.

New York Evening World, April 23, 1894

New York Evening World, April 23, 1894

Jul 13, 2018

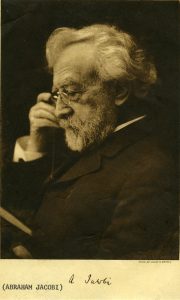

The Arthur H. Aufses, Jr. MD Archives at Mount Sinai is proud to make available two groups of digitized correspondence to and from Abraham Jacobi, MD (1830-1919), the “father of American pediatrics.” Dr. Jacobi was a towering figure both at Mount Sinai, where he chaired the Medical Board for twenty-five years and is the namesake of the Alumni Association’s Jacobi Medallion, and in the broader world of the history of medicine. He was the first Professor of Pediatrics at an American medical school (beginning at New York Medical College and later moving to Columbia), and under his leadership Mount Sinai created the first department of pediatrics at a general hospital in New York City.

This digitized collection is the work of two institutions, the Aufses Archives and the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, which generously made available scanned images of their own collection of Jacobi correspondence. By bringing together two geographically separated collections whose contents overlap in time and subject matter, this digitization project, which includes full transcriptions of all manuscripts, makes Dr. Jacobi’s story more accessible to scholars and the general public. The Mount Sinai letters are available here, and the Historical Medical Library’s letters are available here.

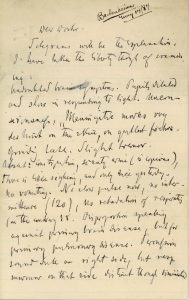

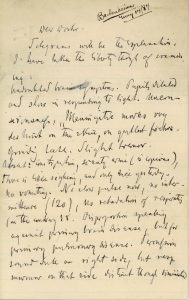

Although the majority of the collection deals with the staffing and administration of The Mount Sinai Hospital and its Out-Door Department (the outpatient clinics), one letter in the collection provides a fascinating glimpse into Dr. Jacobi’s medical practice. In 1884, at the request of an unidentified colleague, he examined an unnamed patient and replied with a brief but dense handwritten note describing his findings. Like modern physicians, Dr. Jacobi used close attention to his patient’s symptoms to perform a differential diagnosis. With no laboratories or high-tech equipment at his disposal, he relied solely on the evidence of his immediate senses, counting the pulse and percussing the chest to make a tentative diagnosis of secondary meningitis brought on by a pulmonary condition.

Dr. Jacobi comments that the “prognosis [is] bad, it is true — but still, who can tell?” His uncertainty tempered with hope reminds us that in hindsight, the decade of the 1880s was a pivotal time for modern medicine, when therapeutics had not yet caught up with rapid advances in accurate diagnosis. Nothing more is known of this patient or his eventual fate.

Jun 29, 2018

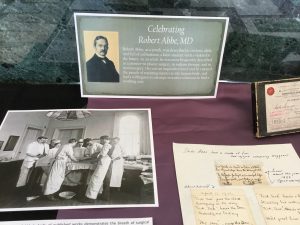

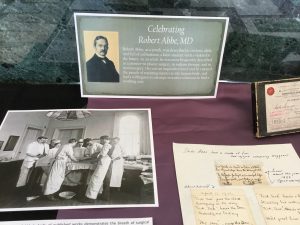

A new exhibit is now on display in the Mount Sinai West hospital lobby. Celebrating Robert Abbe, MD aims to share the many sides of Dr. Robert Abbe: the medical pioneer, the innovator, the artist, and the collector.

A new exhibit is now on display in the Mount Sinai West hospital lobby. Celebrating Robert Abbe, MD aims to share the many sides of Dr. Robert Abbe: the medical pioneer, the innovator, the artist, and the collector.

A native son of New York, Robert Abbe was born on April 13, 1851 and raised on Dutch Street in lower Manhattan. He attended public schools and took evening classes at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art to develop his talents for drawing and painting. He earned an undergraduate degree from the College of the City of New York in 1870 and joined the faculty there after graduation, teaching Drawing, Geometry, and English. He completed an MD degree in 1874 from the College of Physicians and Surgeons, and spent his residency at St. Luke’s Hospital. He later became an Attending Surgeon there, as well as Roosevelt Hospital (now Mount Sinai West), the Cancer Hospital, New York Babies Hospital, Ruptured and Crippled (today’s Hospital for Special Surgery), and Woman’s Hospital.

As a youth, Robert Abbe was described as curious, alert, and full of enthusiasm, a keen student with a vision for the future. As an adult, he was most frequently described as a pioneer – in plastic surgery, in radium therapy, and in neurosurgery. His was an inquisitive mind and he enjoyed the puzzle of repairing injuries to the human body, and had a willingness to attempt inventive solutions to find a working cure.

On view in the exhibit is a small sampling of published articles by Abbe documenting the broad variety of surgeries he performed, including neurosurgery, treatments for various problems of the hand, gallbladder, and cancer of the cheek, jaw, and breast. Later in his career, he wrote on the use of radium in the treatment of various conditions.

Abbe continued to exercise his artistic talents into adulthood, not only as a fine plastic surgeon, but also as a painter. Ever curious to try new things, when the Lumiere brothers of France developed a new method for taking color photos using a glass plate and various salts in 1905, Abbe was quite interested. By 1907 it was available in the US, and Abbe was among the first to experiment with the method by photographing family and friends, producing some lovely images that have a delicate and painting-like appearance. Two of these images are on display in the lobby case.

Another of Abbe’s amusements was collecting documents and photographs of or about famous medical persons. He created scrapbooks on such notables as Louis Pasteur, Benjamin Rush, Edward Jenner, Joseph Lister, and Marie Curie. He also acquired several objects of these notables. Between 1911 and 1923 he donated this collection to the College of Physicians in Philadelphia. On display in the exhibit is a photograph of Marie Curie in her laboratory, and another of the quartz-piezo-electro meter, which she used to determine the strength of electron discharge from radium. In 1921, at Abbe’s prompting, she donated it to the “Abbe Cabinet,” as his collection is called, at the College of Physicians, where it remains on display.

The high esteem in which Abbe was held is documented by his 70th birthday celebrations, which were held at the New York Yacht Club and attended by many friends and relations coming together for a dinner in his honor. On display are two dinner menus for the evening, one of which was autographed on the back by several well-known physicians in attendance. Along with the menu is a bound volume of typed copies of letters he received on the happy occasion conveying best wishes and fond remembrances from colleagues, friends, staff, and former students from around the country. The book is opened to a letter from William J. Mayo, MD of the Mayo Clinic, who was among his students.

During his later years Abbe spent summers in Bar Harbor, Maine where he developed an interest in the Native American population of the area. He began collecting Native American tools and Stone Age artifacts he found. He dreamt of creating a museum to display his extensive collection, raised funds to do so and designed many of the exhibits himself. The museum opened only five months after his passing in 1928. A pamphlet from the museum is included in the exhibit.

Please stop into the lobby at Mount Sinai West and browse the display, which is on view through October.

Please stop into the lobby at Mount Sinai West and browse the display, which is on view through October.

Jun 21, 2018

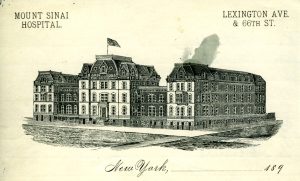

The second site of the Hospital on Lexington Avenue

This is an excerpt from the minutes of the Board of Directors of The Mount Sinai Hospital, March 11, 1888. It is a report from Mr. De Witt J. Seligman, a Director, concerning the proper verification of deaths occurring in the Hospital. The punctuation has not been changed. It provides an interesting view into what was then – and now – a very important issue: how to determine when someone is, in fact, dead.

“Mr. Seligman who was appointed a committee of one…read the following report:

To the Board of Directors of Mount Sinai Hospital:

Having been appointed at the last regular meeting of your Board a Committee of one to look into the matter of certifying to deaths I beg to submit the following report.

In getting at the facts of this matter I have seen three doctors of our visiting staff, the Pathologist of the New York Hospital, the House Surgeon and the House Physician of Mount Sinai Hospital and the Superintendent of Mount Sinai Hospital. There can be no doubt that it happens at times that patients are declared dead before life has become extinct. The Superintendent of our Hospital informs me that on one occasion a nurse told him that her patient was dead and that she was going to announce it to the doctor. The superintendent, Mr. Hadel, went to the Ward and found the alleged dead man sitting bolt upright.

A man informed our Superintendent, Mr. Hadel, that when he was a patient at Blackwell’s Island he was being carried from the Ward to the dead house. On the way they passed through the open air and the effect was that the man on the stretcher became revived and lived to tell this tale of carelessness to our Superintendent. Only this winter a relative by marriage of my wife was, I am informed, declared dead by a physician, but today that same man is as lively as a cricket. Had he been a patient of the Mount Sinai Hospital might he not under our present rules, have ·been hurried from his warm bed in the Ward into the death house and there frozen to death in a short time?

The Pathologist of the New York Hospital informs me that the Ambulance surgeon of the New York Hospital has been repeatedly in doubt as to whether a patient was dead or not and the same Pathologist of the New York Hospital tells me that a certain Dr. Ridlow thought a patient was dead and but two hours later the patient showed life; on the following day Dr. Ridlow again thought that the same patient was dead but even after that on the second day the patient showed life. There was in this case trouble with the heart. An intelligent gentleman connected with the Mount Sinai Hospital as a Director informs me that he and his wife have a mutual agreement by which in the case of the supposed death of one of them, the survivor is to carry out the following agreement: the word of the family physician is not to be taken that death has come but an outside physician is to be summoned to apply the death tests. After that is done no ice is to be placed on the body for 8 hours and the burial is not to take place for three days. In a large institution like ours where deaths are naturally occurring continually, the question arises, what method shall we adopt to avoid the possible mistake of hurrying a supposed corpse into the dead house where in case some life is still in the body it would soon by the sudden change of temperature be frozen out of the body.

One of our visiting physicians whom I saw suggested that the supposed corpse be placed in a warm room for 6 hours and that after 6 hours a second examination be made and then if no sign of life be found place the corps in the dead house. If decomposition has already set in this 6 hours additional precaution, the said visiting physician thought, ought not be taken, nor ought it be taken in warm weather when the cool temperature of the dead house would even aid to revive the flickering flame of life.

This idea seems to me the best idea that was suggested provided it be conscientiously carried out at the Hospital. But whatever rule you may make, one thing is sure and that is that no one but the House Physician on his side and no one but the House Surgeon on his side ought to make the death tests and in each and every case the House Physician or the House Surgeon ought to feel and bear the whole responsibility. To this end I would recommend that we have printed slips which shall run about as follows:

Mount Sinai Hospital, N. Y.

This is to certify that I have this day carefully examined __________________________

a patient of Mount Sinai Hospital in Ward No.____ Bed No.____ and found (him or her) dead.

These slips are to be signed only by the House Surgeon on his side of the Hospital and all these slips are to be kept by the Superintendent of Mount Sinai Hospital in a book for that purpose. In consultations with Drs. Rich and Walsh, the House Surgeon and House Physician of this Hospital, I find that there are no rules as to who shall declare that life has left a patient. Dr. Rich informed me that he always attended to this but Dr. Walsh informed me that in nearly all cases he did and in the remaining cases he left the investigation of the alleged corpse to any doctor, it mattered not which one.

The Pathologist of the New York Hospital informs me that at the New York Hospital the House Physician or the House Surgeon and nobody else testifies to death and even if he has been but a short time previous to death say three times at the bedside said House Physician or House Surgeon is personally compelled to go to the Ward and examine the patient after he has been declared dead. Even at night at the New York Hospital the House Physician or the House Surgeon is compelled to go to the body and examine it.

It may be of interest to you to know that at the New York Hospital every single corpse is washed and put in a shroud and as this operation usually takes half an hour or more, in the opinion of the Pathologist of the New York Hospital who gave me this information, is an additional safeguard against treating the patient as dead before life has left the body.

A great deal more could be written on this important subject, but I think I have written enough to make it clear that this Hospital should have the most stringent rules that can possibly be made in the matter of death certification.

Respectfully submitted

(signed) DeWitt J. Seligman

Mr. [Isaac] Wallach moved that the report of Mr. Seligman dated March 11, 1888 be spread on the minutes in full and that the recommendations contained in said report that the House Physician and House Surgeon must examine persons supposed to have died and sign certificates of death and no one else, in the manner suggested in said report.

That a book be provided for the purpose by the Comm. on Printing.

That the suggestion to place alleged dead persons for 6 hours in a warm room from and during cold months before such bodies are placed in the dead house be referred to the Executive Committee to provide the room if possible.

These provisions are intended as safeguards to prevent the slightest possibility of patients being placed in Dead House who may be apparently dead but not actually so. This whole motion of Mr. Wallach was adopted.

May 25, 2018

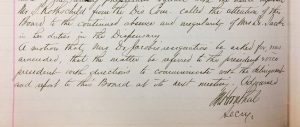

In 1875, The Mount Sinai Hospital selected Mary Putnam Jacobi, MD (1842-1906) to be the Chief of the newly established Children’s Clinic. Abraham Jacobi, MD, her husband, was an important member of the Mount Sinai medical staff and is today considered the Father of Pediatrics in this country. Still, the Trustees did not want him to be in charge of both the inpatient and outpatient services, so Mary Jacobi was appointed. All was well for some years, but in May 1884, the Board of Trustees’ minutes record the “continued absence and irregularity of Mrs. Dr. Jacobi in her duties in the Dispensary.” There was a motion seeking her resignation, but this was amended to instead send the president and vice-president of the Board to speak with “the delinquent” and report back. The subsequent meeting does not have a report on the visit with “Mrs. Dr. Jacobi,” but it is known that she resigned from the staff in October of 1886, more than two years later. Did being “Mrs.” Jacobi save her appointment? Perhaps. The very few other female doctors on staff were known as just Dr. The fact that Mary Putnam was married to Abraham Jacobi probably loomed large in the eyes of the Mount Sinai trustees. He remained associated with the hospital until his death in 1919.

The minutes of the Board of Trustees of The Mount Sinai Hospital, May 1884

May 18, 2018

By some remarkable coincidence, many Mount Sinai Health System buildings have been dedicated or opened in May.

The Beth Israel Hospital opened its first facility in a rented loft in May 1890 and then moved to 196 Broadway the next year. In May of 1892 they moved again, this time to 206 E. Broadway and 195 Division St. Beth Israel remained at this location until the completion of the Jefferson & Cherry Street building in 1902. Beth Israel did not have another May opening until May 15, 1966 when the Linsky Pavilion opened.

Beth Israel’s Jefferson and Cherry Street location

The Linsky Pavilion, which opened in May 1966

On May 17, 1855, a religious service was held to inaugurate the opening of The Jews’ Hospital in the City of New York, which became The Mount Sinai Hospital in 1866. Presiding at the inauguration was Rabbi J.J. Lyons, with Rabbis Leo, Sternberger, Rubin, Cohen, Waterman, Schickler and Tebrich serving as cantors.

The original building of The Mount Sinai Hospital

The second site of the Hospital

When Mount Sinai had outgrown this site, the Trustees decided to move uptown to the block of Lexington Avenue between 66th and 67th Streets. The cornerstone for the new hospital was laid on May 25, 1870 and the completed hospital was opened on May 29, 1872.

The 1904 building along 100th Street

Within 25 years, the Hospital had again filled its site and decided to move to its current home next to Central Park, between 100th and 101st Streets. The Park ensured that the hospital would not again get surrounded by the bustle of the City’s streets. The cornerstone for this new hospital was laid on May 22, 1901. In May 1922, Mount Sinai marked the completion of a massive expansion project that extended the hospital across 100th Street down to 99th Street. This included 1184 5th Avenue, which today is the oldest building on the Mount Sinai campus.

On May 23, 1952, The Mount Sinai Hospital celebrated the dedication of the Klingenstein Pavilion on 5th Avenue.

This was built as Mount Sinai’s Maternity Pavilion, and remains the home of our OB-GYN department. At the same event, the Atran Laboratory and the Henry W. Berg, MD Laboratory buildings were both dedicated as well.

The Klingenstein Pavilion on 5th Avenue

Vice President Ford and Walter Annenberg looking at the portrait of Mrs. Annenberg at the dedication in 1974

And finally, in perhaps Mount Sinai’s biggest dedication, on May 26, 1974, the new Mount Sinai School of Medicine welcomed Vice President Gerald Ford and the Annenberg family to celebrate the formal dedication of the Annenberg Building. When this building opened, it was the thought to be the largest space in this country devoted to medical education.

St. Luke’s Hospital on 5th Avenue

The Mount Sinai Hospital was not alone in its fascination with May for buildings. On May 21, 1857, the St. Luke’s Hospital chapel opened at the Hospital’s first site and a year later (May 13, 1858) the hospital itself opened at 5th Ave between 54th and 55th Streets.

The Woman’s Hospital in the State of New York, which became the Women’s Division of St. Luke’s Hospital in 1952, also had a May dedication tradition. On May 4, 1855 the Woman’s Hospital was opened at 83 Madison Avenue. Almost 50 years later, on May 17, 1904, the cornerstone was laid at a new site at Amsterdam Avenue and 110th Street.

The first home of the Woman’s Hospital

The 1904 west side Woman’s Hospital building

Finally, on May 25, 1965 the Woman’s Hospital opened in a separate building on the St. Luke’s campus on Amsterdam Avenue and 114th Street.

Apr 24, 2018

As the spring very slowly arrives, the tired mind often screams for relief from the challenge of processing complex information. So, here is some Mount Sinai trivia that is guaranteed to interest without straining the brain.

Did you know:

…that in the 17th century there were Native Americans living in East Harlem and there was a stream flowing where the Icahn building now stands?

…that the first year The Mount Sinai Hospital was opened (1855-56), we admitted 216 patients, only five of whom were born in the US, and three of them listed their careers as comedians?

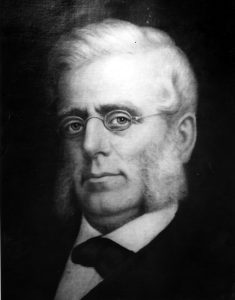

Mount Sinai founder, Benjamin Nathan

…that The Mount Sinai Hospital had a well regarded nursing school that existed from 1881-1971 and that 5 E. 98th Street was the School of Nursing dorm/educational building?

…that when the Hospital moved to its second site at Lexington Ave. and 66th St. in 1872, the Trustees built a large synagogue upstairs and a small operating room in the basement?

…that a Mount Sinai founder, Benjamin Nathan, was murdered in his sleep on a stormy night, and members of his family are still on the Board to this day?

…that Mount Sinai did not have an obstetrical service for the first century of its existence, only offering an OB Service when the Klingenstein Pavilion opened in late 1952?

…that there is a time capsule buried under the directory in the Annenberg Lobby that is scheduled to be opened in 2074, 100 years after it was placed there?

…that Jonas Salk and Henry Heimlich both served their internships at Mount Sinai, Salk graduating in 1942 and Heimlich in 1948?

…that in 1964, Mount Sinai had 1,326 beds, 200 more than we have today?

…that when the first ICU opened at Mount Sinai in 1962, it had five beds and was located in 1184 Fifth Ave., on the 7th floor?

…that in 1993 Mount Sinai School of Medicine became the first in New York State to graduate a class with more women than men?

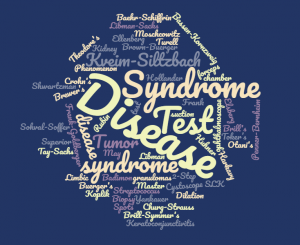

…that there are at least 43 diseases, syndromes, tests, instruments and phenomena named after Mount Sinai physicians and scientists?

Apr 6, 2018

The photograph above shows the house staff of the Beth Israel Hospital in 1913. By that year, Beth Israel had been active for 24 years, and since 1902 it had been located on Jefferson & Cherry Streets, where this photograph was taken. (The hospital moved to its current location on Stuyvesant Square in 1929.) Although Beth Israel was still a relatively young hospital, it was already a state-of-the-art medical facility, with modern operating rooms, a radiology department, and laboratories for pathology and physiological chemistry. The hospital had a house staff, the precursor of the modern residency system, on which recent medical school graduates would spend two years living at the hospital and acquiring clinical experience.

When the Aufses Archives first acquired this photograph, the identity of the woman standing in the back row was unknown. There were two prints of the photograph in the collection, and they were labeled with conflicting dates, neither of which seemed correct. One print was labeled 1929, but this could not be right, since the clothing appeared wrong for that date and the photograph was clearly taken at the Jefferson Street location. Another was labeled 1908, but in this case, who could the woman have been? The earliest known female doctor associated with Beth Israel was Nettie Shapiro, MD, who served a one-year term as a non-resident extern in 1909, but a comparison with other photographs of Dr. Shapiro showed that it wasn’t her.

The identity of the woman in the photograph remained a mystery until recently, when we discovered a newspaper article in a collection of clippings that provided the answer. The woman in the photograph is Sophie Rabinoff, MD, who was the first female member of the Beth Israel house staff. Born in Russia in 1889, the same year Beth Israel was founded, Dr. Rabinoff came to the United States as a baby with her immigrant parents. She grew up in New York City, where she attended Hunter College before receiving her MD degree from the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia.

Like other female medical students of her time, in addition to the challenge of mastering the med school curriculum, Dr. Rabinoff had to overcome prejudice against women to continue pursuing a medical career. As the article describes, before taking the competitive examination for the Beth Israel house staff, she had to persuade the hospital management to allow her to sit for the exam. It was only after she came in first out of 31 candidates, ahead of 30 men who also took that year’s examination, that she was admitted. Unlike her predecessor Dr. Shapiro, who as an extern did not live in the hospital or serve the full two-year term, Dr. Rabinoff became a full member of the house staff, with all the accompanying responsibilities and privileges. Unfortunately, 1913 is one of the few years for which the Aufses Archives does not have the minutes of Beth Israel’s trustees or medical board, so we have no record of the debates that might have accompanied her admission.

The photograph in the newspaper article was clearly the same person as the woman in the photograph, confirming that this was an image of Dr. Rabinoff and the rest of the 1913 house staff. A search for additional information on Dr. Rabinoff revealed that she went on to a distinguished career in public health, as documented by her entry in the Jewish Women’s Archive Encyclopedia. After her time at Beth Israel, Dr. Rabinoff served with a Hadassah medical mission in Palestine before returning to New York and becoming a public health officer. She worked for two decades for the Department of Health, where she was responsible for overseeing public health programs in various parts of Manhattan and the Bronx, before joining the faculty of the New York Medical College in 1939. At her passing in 1957, she had recently retired as Director of the College’s Department of Public Health and Industrial Medicine.

Mar 23, 2018

A new finding aid for The Col. Henry H. M. Lyle Collection of World War I Photographs and Documents, 1916-1943, was recently published and made available to researchers on-line (http://icahn.mssm.edu/about/ait/archives/collection/henry-lyle). The collection includes 200 photographs from World War I, maps and documents used during the war, some correspondence, and reprints of articles by Lyle.

A new finding aid for The Col. Henry H. M. Lyle Collection of World War I Photographs and Documents, 1916-1943, was recently published and made available to researchers on-line (http://icahn.mssm.edu/about/ait/archives/collection/henry-lyle). The collection includes 200 photographs from World War I, maps and documents used during the war, some correspondence, and reprints of articles by Lyle.

The heart of the collection is the photographs taken in France during World War I, which depict often dramatic or surprising images of the war. There are views of hospital stations, barracks, and outdoor equipment (some include large defensive weapons), transportation of wounded soldiers, field dressing stations, supply trains, and troops on the battlefields. Interior views document soldiers, patients, operating rooms and special treatment rooms. A number of the images display the effects of mustard gas and other brutal wounds sustained by soldiers, while others capture the unit compound against the French countryside in an oddly artistic fashion. Still others provide a view of everyday life in the compound – washing clothes, unloading shipments of supplies and such, but which brings to life the challenges of a large group of people living in one spot at that point in time. Laundry meant picking lice off of clothes; unloading supplies meant huge piles of boxes; transporting wounded soldiers sometimes meant walking through ankle-deep mud. The collection also captures images of foreign soldiers in national uniforms, some riding horseback, a lifestyle that is very different from the standard U.S. soldier’s, which adds an interesting, and occasionally humorous, side to the war.

Henry Hamilton Moore Lyle, MD, was a noted surgeon and decorated soldier. He was born in Northern Ireland in 1874. His family immigrated to Ontario, Canada when Lyle was a boy. He graduated Cornell in 1896, and went on to Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, graduating in 1900. He took an internship at St. Mary’s Hospital for Children and at New York Hospital and a year’s surgical internship at St. Luke’s Hospital (1901-1902) before joining St. Luke’s surgical staff in 1904 and where he remained on staff until his death.

It appears that Lyle spent the year between his internship and surgical appointment traveling abroad, visiting clinics in Great Britain, France and the German-speaking countries. This familiarity with Europe may have led to his voluntary enlistment in World War I two years before the U.S. was formally involved in the conflict. In 1915 he took leave from his private practice and hospital positions in New York and spent six months as Chief Medical Officer of American Ambulance Hospital B, Juilly, France.

In 1916 he again took a leave and returned to France to serve for several months as Chief Surgeon of Ambulance d’Annel (Longueil, France). In April 1917 when the US entered the conflict, he joined the U.S. Army Reserve and in May was ordered to active service. In June he organized the United States Army Evacuation Hospital No. 2 at Camp Benjamin Harrison, and was appointed its commander when it left for France in January 1918.

In September 1918, Lyle was made Director of Ambulances and Evacuation of the Wounded for the First Army. During the ensuing Meuse-Argonne offensive, over 125,000 sick and wounded were brought to the railhead hospitals under his supervision. In recognition of his outstanding service, particularly during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, where the Evacuation Hospital No. 2 played a major role as one of two front line hospitals established in the Zone of Combat, he was decorated with the Distinguished Service Medal (U.S.). Lyle was also awarded the British War Medal and the British Victory Medal.

When the war ended Lyle returned to New York and medical practice at St. Luke’s Hospital, where his reputation as an outstanding surgeon followed his successes in battle. Lyle retired from medical practice in 1938, though remained a Consulting Surgeon at St. Luke’s until his death from coronary thrombosis on March 11, 1947.