Mar 26, 2021

Women have been active contributors to Mount Sinai Beth Israel since its founding in 1890. From the Ladies’ Auxiliary formed in MSBI’s first year of operation, to the first female House Staff member Dr. Nettie Shapiro in 1909, to so many on our front lines today, women’s contributions have always been essential to the operation of the hospital. This year for Women’s History Month, we’ll be featuring Dr. Marie Nyswander (1919-1986), a psychiatrist and an early leader in methadone maintenance in the treatment of heroin addiction.

Dr. Nyswander was born in Reno, Nevada, and graduated from Sarah Lawrence College (1941) and Cornell University Medical College (1945). From there she joined the Public Health Service in Lexington, Kentucky, where she first worked with patients with addiction issues. She later received psychiatry training at New York Medical College, and published a book, The Drug Addict As A Patient, in 1956. The book was among the first which argued for treating addiction as a medical problem, rather than a moral failing, likely influenced by the dramatic increase chemotheraputic treatments for psychiatric disorders in the 1950s. She went on to chair the New York City Mayor’s Advisory Board on Narcotics in 1959 and worked at a clinic in East Harlem throughout the early 1960s, alongside her own private practice.

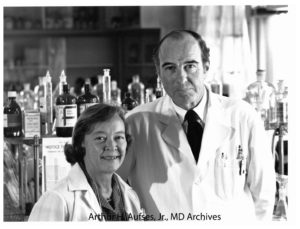

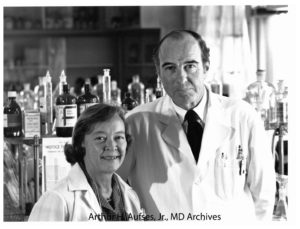

Photograph of Drs. Nyswander and Dole

In 1964, she was invited by Dr. Vincent Dole, a physician at Rockefeller Hospital, to join a study on the biology of addiction, which ultimately led to the discovery of methadone as a treatment for heroin addiction. Drs. Nyswander and Dole married in 1965. From the late-1960s until her death in 1986, she was affiliated with Beth Israel Hospital, where thousands were eventually treated through the Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program. She also served on the President’s Advisory Board for Mental Health during the Carter administration. Both she and her work with Dr. Dole received many honors.

Article from January 20, 1969 issue of “Drug Topics”

Dr. Nyswander was a fierce defender of what has been a controversial treatment since its inception. Though detractors argue that methadone replaces one opioid addiction for another, Nyswander and Dole saw that abstinence-focused treatments were not always effective and that the symptoms of withdrawal caused by detoxification were needlessly challenging and painful for the patient. Methadone, an opioid itself, prevents drug cravings and blocks the ‘high’ of heroin.

Dr. Nyswander passed away in 1986 at the age of 67.

Sources:

Courtwright, David T., “The prepared mind: Marie Nyswander, methadone maintenance, and the metabolic theory of addiction,” Addiction 92, vol. 3 (1997): 257-265. Accessed March 23, 2021.

Dole, Vincent, Biographical photographs, Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

“Dr. Marie Nyswander Dies at 67; Expert in Treating Drug Addicts,” The New York Times (New York, N.Y.), April 21, 1986. Accessed March 23, 2021.

Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program clippings, AA088.S003.SS001.B003.F029 – AA088.S003.SS001.B003.F047, Mount Sinai Beth Israel collection, Arthur H. Aufses, Jr., MD Archives at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Jun 4, 2020

An update to this blog post can be found here.

Founded in 1892, the early history of Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital was decorated with a series of success stories in the treatment of disease. Against the background of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, then affected by poverty, close living quarters, and dangerous working conditions, its residents, largely recent Jewish immigrants, were made vulnerable to many of the contagious diseases of that era. In its first years, Beth Israel contributed research to combat the typhoid epidemic of 1906-1907, established an after-care clinic to children affected by the 1916 polio epidemic, and is credited with finding the cure for trachoma, which had previously been a cause to turn away new immigrants at Ellis Island.

Only twenty-five years after Beth Israel’s opening, the United States was embroiled in the first World War. The Hospital encouraged its medical staff to join the Medical Reserve Corps, with approximately half of its doctors signing up. The Hospital had also encouraged its nurses, physicians and other staff to join the war effort.

This left Beth Israel in a precarious position when the 1918 Influenza epidemic reached New York City. Being chronically understaffed, Beth Israel’s Medical Board contacted the Department of Health for advice. The response was simply: “There is nothing to advise except the use of gauze masks which did not always prevent the disease.” In November 1918, the Hospital eliminated visiting hours, curtailed teaching hours, and turned the Male Medical Ward over to the Department of Health to use as an isolation facility for the pandemic. (The DOH never used the facility because they were similarly understaffed.)

Female ward of Beth Israel Hospital, Jefferson and Cherry Street, circa 1910

Ultimately, Beth Israel was only able to admit twenty-nine influenza patients. (Update: This number is disputed in other sources.) Seven members of the House Staff were awarded $25 (approximately $500 today) for “self-sacrificing services performed” and the Hospital offered special incentive pay to doctors and nurses to help combat the fact that they were understaffed.

Despite the limited patient intake, Beth Israel’s contributions to the 1918 flu pandemic were still impactful. In December 1918, Superintendent of the Hospital, Louis J. Frank, contacted Presidents Roosevelt and Taft to encourage universal nursing training in the education of women, likely in response to the chronic under-staffing at this time. By January 1919, many of the patients in the Hospital were admitted for “post-influenzal complications” leading to the care of many affected by the pandemic.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

May 13, 2016

As the Mount Sinai Archives continues processing and cataloging the records of the Beth Israel Medical Center (today’s Mount Sinai Beth Israel), we continue to discover interesting images and ephemera from Beth Israel’s history.

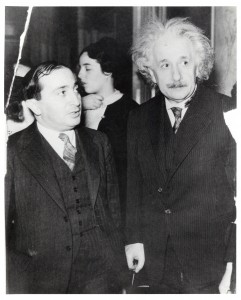

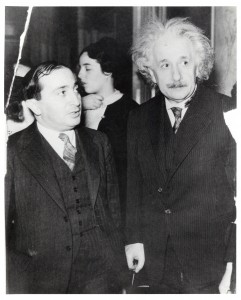

The photograph above shows Albert Einstein with Adolph Held (1885-1969), editor of the Jewish Daily Forward and brother of Dr. Isidor W. Held, a longtime member of the Beth Israel Hospital medical staff who served as President of the Medical Board from 1936 to 1938. (Update June 2017: When we first discovered this photograph in the collection, it had been incorrectly identified as a photograph of Dr. Held rather than his brother Adolph. Thanks to the family member who contacted the Archives with a correction.)

Dr. Held, a gastroenterologist, was involved in Jewish refugee aid in the aftermath of World War I, and during the rise of Nazism he became active in the movement to help medical and scientific emigres escape from Nazi Germany and its conquered territories, raising funds and publishing articles on behalf of persecuted Jewish physicians. These activities brought him into contact with Albert Einstein, who was himself a refugee from Nazi persecution and a vocal activist on behalf of other potential emigres.

This photograph is the only item in the Beth Israel collection that documents the relationship between Einstein and Dr. Held, but the Einstein Archives Online, a comprehensive directory of Einstein’s manuscripts, includes numerous entries for letters to and from Held and his wife Fanny. In 2006, a 1938 letter from Einstein to Held discussing the situation in Germany was sold at auction; the catalog listing includes a translation of the letter, which discusses their unsuccessful attempts to help an internist named Rudolph Ehrmann escape the “German gangsters.” (The following year, they were successful in obtaining passage to New York City for Dr. Ehrmann, who opened a private practice and became one of Einstein’s personal physicians.)

Dr. Held passed away in 1947. In addition to his legacy as an administrator, clinician and teacher of house staff, and the lives he saved as a refugee advocate, his posthumous impact at Beth Israel included an important annual lecture series endowed in his memory, which lasted until at least the late 1980s and brought numerous prominent physicians to BI’s downtown campus.

Mar 25, 2016

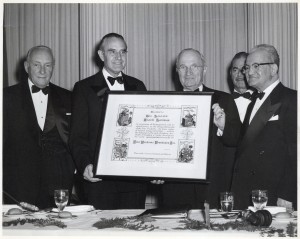

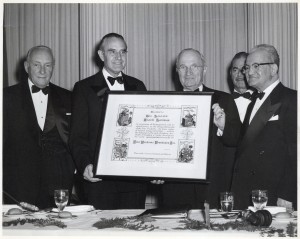

The Mount Sinai Archives continues to process a recently received collection of records and photographs that document the history of the Beth Israel Medical Center, today’s Mount Sinai Beth Israel. Among the many fascinating documents in this collection are a collection of photographs and news clippings that document the life of Charles H. Silver, who served for 35 years as the Chairman of Beth Israel’s Board of Trustees. The child of an impoverished Romanian Jewish immigrant family on the Lower East Side, Silver left school at age fifteen to become an office boy at the American Woolen Company, where he worked his way up the sales ranks and eventually retired as Vice President and Director.

Alongside his role as a hospital philanthropist, Silver was active in interfaith relations and worked to strengthen the relationship between New York City’s Jewish and Catholic communities, becoming a close confidante of Francis Cardinal Spellman, Archbishop of New York, and his successor Terence Cardinal Cooke. In 1948 Silver served as chairman of the first Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner, which raises funds for Catholic charities. In gratitude for his exceptional fundraising efforts, the proceeds of which would help support New York City’s Catholic hospitals, Cardinal Spellman presented him at the dinner with a surprise donation to Beth Israel. The Al Smith Dinner remains an important event in national politics, as it is traditionally the last event at which the two major-party candidates for President of the United States share a stage before the election.

Above: Charles H. Silver, Governor Averell Harriman, President Harry Truman and others at a ceremony in honor of Harriman.

Above: Charles H. Silver, Governor Averell Harriman, President Harry Truman and others at a ceremony in honor of Harriman.

Above: Richard Nixon, Charles H. Silver, Hubert Humphrey, Terence Cardinal Cooke, President Lyndon Johnson, Margaretta “Happy” Rockefeller and Governor Nelson Rockefeller at the 1968 Al Smith Dinner.

Above: Richard Nixon, Charles H. Silver, Hubert Humphrey, Terence Cardinal Cooke, President Lyndon Johnson, Margaretta “Happy” Rockefeller and Governor Nelson Rockefeller at the 1968 Al Smith Dinner.

In addition to his medical and political interests, Silver was a strong advocate of public education and served for six years as Chairman of the New York City Board of Education. The Silver collection in the Mount Sinai Archives includes photographs of Silver with every U.S. President from Truman to Carter, two of which are presented here. No full-length biography of Silver has yet been written, but his eventful career is an important part of the story of New York City in the twentieth century.