Sep 14, 2021

The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing diploma program officially closed 50 years ago in 1971. At that point, it had existed for 90 years and had graduated 4,700 students, including the one and only  male student in the last class. (A complete history of the School is available here.) Many hospital diploma schools closed during the 1970s, including the St. Luke’s Hospital and the Roosevelt Hospital Schools of Nursing, both in 1974. This wave of closings was due to the schools being fiscal drains on the parent hospitals, as well as the changing educational standards professional nursing organizations championed, including the baccalaureate degree as the best entry-level credential for nurses.

male student in the last class. (A complete history of the School is available here.) Many hospital diploma schools closed during the 1970s, including the St. Luke’s Hospital and the Roosevelt Hospital Schools of Nursing, both in 1974. This wave of closings was due to the schools being fiscal drains on the parent hospitals, as well as the changing educational standards professional nursing organizations championed, including the baccalaureate degree as the best entry-level credential for nurses.

By the mid-1960s, the Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing was at a crossroads, trying to find a way to move forward in the face of these trends. In 1967, the newly formed Mount Sinai School of Medicine affiliated with The City University of New York (CUNY). This triggered a review of other possible interactions between the two institutions. That year, the School of Nursing joined with Hunter College, a part of CUNY, to start offering elective humanities credit to the students, easing their path to an eventual baccalaureate degree.

The next twist appeared in the Hospital’s Annual Report for 1968: “This has been a milestone year for the Department of Nursing. Negotiations with the City University led to the joint announcement of a baccalaureate program in nursing to be launched in September 1969 with the [Mount Sinai] Director of Nursing holding the position of Dean of the School of Nursing. Alumnae, staff and students have all expressed enthusiasm at the forward step. They are particularly pleased at the acceptance of the name, The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing at The City College.”

And so it was, but only briefly. The first class was admitted to the program in fall 1969, along with a sophomore group that had started at Sinai, and a graduation ceremony was held in 1972 for thirteen students. However, the two institutions could not work out long-term arrangements and so the relationship was terminated by 1974.

And so it was, but only briefly. The first class was admitted to the program in fall 1969, along with a sophomore group that had started at Sinai, and a graduation ceremony was held in 1972 for thirteen students. However, the two institutions could not work out long-term arrangements and so the relationship was terminated by 1974.

The closing of the School left behind a saddened but vibrant Alumnae Association that continues to serve its members and The Mount Sinai Hospital today.

Aug 18, 2021

The Upper East Side home of The Mount Sinai Hospital and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai spans continuously from 101st St down to 98th Street, with other buildings arrayed nearby. To achieve this continuous campus, what had once been 99th and 100th Streets between Madison and Fifth Avenues have disappeared. How and when did that happen?

View along 100th St., around 1937

The Mount Sinai Hospital moved to 100th Street in 1904, taking up the whole block between the avenues and up to 101st Street. In 1911, the Hospital started buying lots on the south side of 100th Street in anticipation of a large expansion program. By 1921, those new buildings stretched from Fifth Avenue across but not quite to the end of 100th Street. The street was used for physician parking, and in December 1949, New York City deeded the bed of 100th Street to Mount Sinai. It continued as parking for a few more decades, but with the construction of the Guggenheim Pavilion starting in 1986, the street disappeared into a plaza between the original buildings and the new.

The story on 99th Street is very similar: Mount Sinai had expanded to having buildings spread along the northern side of the block. At the end of the 1950s, when construction of the Klingenstein Clinical Center (KCC), fronting onto the corner of Madison and 99th Street, was being planned, Mount Sinai sought the help of the City, and in August 1958, the road bed of 99th Street was deeded to Mount Sinai.

And what about the former streets? Once the construction on KCC was finished, this area became known as the Hospital Gardens, and graduation ceremonies for our School of Nursing, as well as special events were held out there. The plaza across 100th Street was covered in bricks, and a large sculpture called La Sfera Grande by Arnaldo Pomodoro was placed there in 1974. In the late 1960s, all of the buildings along the former southern side of 100th Street and the northern side of 99th Street were torn down to make way for the Annenberg Building. The Gardens became Ross Park, and today the Sfera Grande sits adjacent to the Nathan Cummings Atrium in the Guggenheim Pavilion. This is only appropriate since Mr. Cummings had originally given Mount Sinai the sculpture.

Nursing School graduation in the ‘Gardens’ in 1961. Note that KCC is being built in the back left of the image.

Nov 9, 2020

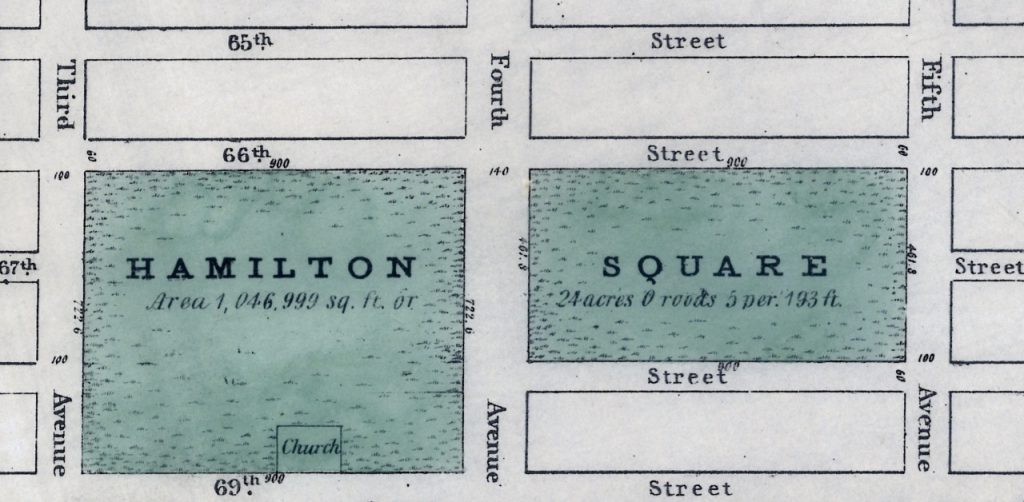

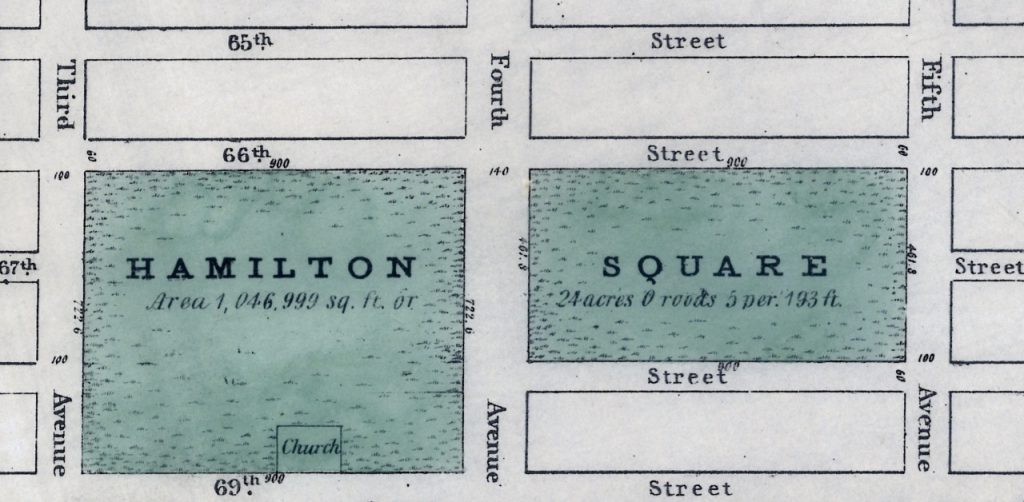

I recently read a piece about Hamilton Square in the Roosevelt Island Historical Society’s From the Archives email. This park, which was named for Alexander Hamilton, existed on the Upper East Side of Manhattan from around 1807-1869. I found this fascinating since The Mount Sinai Hospital moved to Lexington Ave. and 66th St. in 1872. I knew that the City had ‘seeded’ this area with non-profit entities: Hunter College, many hospitals and schools, but I had never heard about the Square itself, which ran from 66th to 69th Streets between 3rd and 5th Avenues. Finally, Mount Sinai had a Hamilton connection, even though he died in 1804, 48 years before the Hospital was created!

Map of Hamilton Square from the New-York Historical Society

When the Square was broken up, The Mount Sinai Hospital (MSH) was located on W. 28th Street, between 7th & 8th Avenues. It had been founded in 1852 as the Jews’ Hospital in the City of New York (the name was changed in 1866) and had opened its first building in 1855. After the Civil War, the leadership realized that the facility was inadequate and the location less than ideal due to the growth of the City. On November 2, 1867 the Directors authorized the purchase of ten lots of land from 65th to 66th Street on the west side of Park (then 4th) Ave. and later added eight more lots there. But then on October 6, 1868, the City leased Mount Sinai twelve lots of land between 66th and 67th on Lexington Ave. for $1 a year for 99 years. Somehow, over the interim, the City and Mount Sinai had reached an agreement on the Hospital taking over part of the former Hamilton Square. The earlier lots were later sold, saving Mount Sinai thousands of dollars. On May 25, 1870, the cornerstone for the second MSH was laid. The President of the Hospital, Benjamin Nathan, and Mayor Oakley Hall were there. (Within two months, Nathan was murdered in his bed on a ‘dark and stormy night.’)

On May 29, 1872, a dedication ceremony was held for the new Mount Sinai Hospital. When the building opened, it had a greatly expanded capacity of 110 beds. The building was designed by the well-known architect, Griffeth Thomas, and cost $335,000 to complete. It had an operating room in the basement of the north wards, rooms for our newly created House Staff to live in, a meeting room for the Directors, and a synagogue. Lexington Ave. remained unpaved for two more years, and the Hospital never wired the facility for electricity. A telephone was installed in 1882; the number was “Thirty-Ninth St., 257”. It was at this site that Mount Sinai transformed into what we would recognize as a modern hospital, with medical education and research joining its core mission of providing patient care.

In typical Mount Sinai fashion, this facility quickly became too small. Additional buildings were built and major renovations were begun in 1882. In 1890, Mount Sinai added a building across from the Hospital on the north side of 67th St. for our nursing school and Out Patient Department. This building is the only remnant of Mount Sinai that remains there today. It later served as the home of the Neurological Institute, the Polish legation, and finally became a school for the Archdiocese of NY. The Mount Sinai Hospital moved from Lexington Ave. in 1904 to its current East Side location on 100th St., between Madison and 5th Avenues. The name of Hamilton continues on various buildings and neighborhoods of the City, making its most recent appearance on Broadway.

Jul 6, 2020

This started out as a story about Althea Gibson, the first African American to win at Wimbledon, which she did on July 6, 1957. It was also about a summer sport, and being outside – two things people today find important and hopeful. But, as often happens in the Archives, those stories reminded us of other stories, which are, of course, about Mount Sinai.

In 1950, Harlem-born Althea Gibson made her U.S. Open debut at a time when tennis was largely segregated. On July 6, 1957, when she claimed the women’s singles tennis title, she became the first African American to win a championship at London’s All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, aka Wimbledon. (Arthur Ashe was the first African American to win the men’s singles crown at Wimbledon in 1975. Ashe later had quadruple bypass surgery at St. Luke’s Hospital in 1979.) The Associated Press named Althea Gibson Female Athlete of the Year in 1957 and 1958. During the 1950’s, Gibson won 56 singles and doubles titles, including 11 major titles. Gibson retired from tennis and later became a professional golfer. She was voted into the National Lawn Tennis Association Hall of Fame in 1971 and died in 2003.

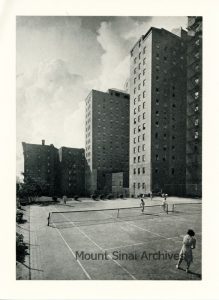

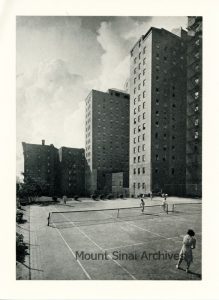

The Mount Sinai Hospital tennis courts on 5th Ave and 99th St, behind 5 E. 98th St., where KP is today.

Tennis has a long, up-and-down history at Mount Sinai. The first tennis court was built at the Hospital in the late 1800’s, back when the Hospital was still located at Lexington Avenue and 67th St. Space was tight, so the court was built between buildings, and the only way to get to it was to climb through a window on one of the wards. (Fortunately, a gong would sound whenever an Attending arrived at the Hospital, so the players were warned to get back inside.) In 1904, Mount Sinai moved uptown to 100th St., and it took 20 years before tennis returned. The growing House Staff asked the Trustees to build tennis courts that they could use for exercise. The Trustees

A small pewter trophy belonging to Noreen McGuire, School of Nursing Class of 1932. The trophy was for winning the tennis tournament in 1929.

eventually agreed in June 1923 and two courts were built on the southeast corner of 99th St and 5th Ave. Mount Sinai had purchased the land for future expansion needs, but had recently completed major additions to the campus and had no immediate plans to build. The courts were used by the Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing for gym classes, and nurses and doctors could sign up to play when a court was free.

The Aufses Archives has a wonderful interview with Gus Burton from 1988. Mr. Burton joined Mount Sinai’s staff in 1948, first as an x-ray file clerk, and then later trained as a technician in the Dept. of Radiology. What initially attracted him to work at Mount Sinai was because there was a tennis court. Here is how he described it:

Burton: …Back in those days the buses that ran along Fifth Avenue were owned by a company called the Fifth Avenue Bus Company. They had double deckers. The top deck was so that you could ride the bus for a nickel. At the time I was a student at NYU and sometimes I would take the bus down because the classes were at Washington Square. It was almost like a bus tour going down Fifth Avenue, seeing all the different places, and I saw the Hospital. I wasn’t impressed with the hospital so much, but where Klingenstein is there used to be tennis courts. At that time I was an avid tennis player, and I could see these people playing tennis. I thought it was very, very interesting, because I had found that there weren’t many places to play tennis in New York and here these people were running around playing tennis. Eventually, one day I was coming back home and I got off the bus. It was approaching the end of the semester and I said I need to find some kind of work for the summer. It was raining pretty hard, so I ran under the canopy that they had by the [Guggenheim] Pavilion. So I said, let me just check in here and see what’s going on. In those days, they didn’t really have what you call a personnel office. I guess they called it an employment office. They had about one or two clerks and the person who ran it, a Mr. Kerr (?). I just walked in and asked them if they had any jobs available. Said Mr. Kerr, “we may have some available in the radiology department. We’ll refer you to the person there who is looking for somebody and see what happens.”

So I went over and I was interviewed by a Dr. Joan Lipsay. She was the second in command in the radiology department. She was just really impressed that I came along and, sure, we’ll take you and they hired me as an X-ray file clerk. So I have always said in the years since then, that I had enough sense to come in out of the rain.

Interviewer: Did you ever get to play tennis?

Burton: Well, I found out after I started working here that those tennis courts were for the professional staff, the doctors and the nurses, and they were the ones I had seen playing on them. It so happened that one of the radiologists on our staff was an avid tennis player, he used to play out there frequently so I was able to get with him and I did get a chance to play on those tennis courts.

Unfortunately for Mr. Burton, the tennis courts were closed later in 1948, when Mount Sinai began the process of building the Klingenstein Pavilion along 5th Ave. It would be 65 years before tennis came back to Mount Sinai, but this time it was in a much different form. In 2013, it was announced that The Mount Sinai Medical Center was now the official medical services provider for the United States Tennis Association (USTA) and the U.S. Open. In addition, Alexis C. Colvin, MD, from the Leni and Peter W. May Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, would serve as the USTA’s Chief Medical Officer. In 2020, this continues to be the case. Every now and then, a mini-tennis court is built in the Guggenheim Pavilion lobby to showcase the Hospital’s role with the USTA, and for a brief moment, tennis is played again at Mount Sinai.

May 12, 2020

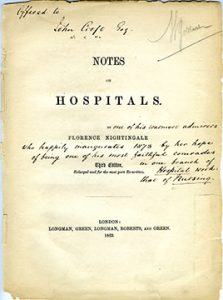

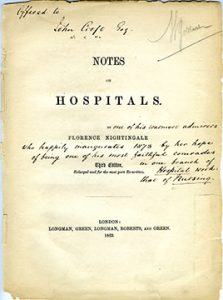

This year the world marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Florence Nightingale (1820-1910.) Her name is known around the world and nurses everywhere enjoy the fruits of her labors today. She lived a long time ago in a very different world, but she enunciated the basic philosophy of modern nursing, and introduced statistics into the study of disease.

The Aufses Archives has copies of two of Miss Nightingale’s books: Notes on Nursing and Notes on Hospitals. The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing, which existed from 1881-1971, had a small collection of Nightingale letters that they had gathered over the years. Some of these were given to the Columbia University School of Nursing in 1953, as shown in the image below.

From the Aufses Archives

Hospitals, schools of nursing, archives, and history of medicine collections will be marking the 200th anniversary of Florence Nightingale this year with celebrations, blog posts, exhibits and lectures. Here are links to just a few of those celebrations going on this year:

Nightingale: Lady and Legend at the National Library of Medicine: https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2020/05/12/nightingale-lady-and-legend/ This includes this note on sources: The National Library of Medicine’s holdings of Nightingale materials are (unsurprisingly) extensive, with over seventy printed titles and editions. In addition, the Library holds a group of Nightingale letters written between 1845 and 1878, all of which may be read as part of the Florence Nightingale Digitization Project, and a copy of an oral history interview conducted by M. Adelaide Nutting (herself a giant in the history of nursing) in 1890. A transcript is available at http://oculus.nlm.nih.gov/2935116r.

A blog post on the University of Maryland, Baltimore School of Nursing ties to Nightingale: https://www2.hshsl.umaryland.edu/hslupdates/?p=4177

A blog post at the UCLA Library about the Elmer Belt FN Collection and other Nightingaleiana we have and use: https://www.library.ucla.edu/blog/special/2020/05/11/happy-birthday-florence-nightingale

Finally, there is a special exhibit at the Florence Nightingale Museum in London called Nightingale in 200 Objects, People & Places https://www.florence-nightingale.co.uk/200objects/ Sadly, the Museum is closed due to the pandemic and is struggling financially. As they note:

Nursing, washing your hands and evidence based-healthcare, pioneered by Florence Nightingale, have become more important than ever before and we’re calling upon our friends and supporters to help us preserve her story and legacy.

male student in the last class. (A complete history of the School is available here.) Many hospital diploma schools closed during the 1970s, including the St. Luke’s Hospital and the Roosevelt Hospital Schools of Nursing, both in 1974. This wave of closings was due to the schools being fiscal drains on the parent hospitals, as well as the changing educational standards professional nursing organizations championed, including the baccalaureate degree as the best entry-level credential for nurses.

male student in the last class. (A complete history of the School is available here.) Many hospital diploma schools closed during the 1970s, including the St. Luke’s Hospital and the Roosevelt Hospital Schools of Nursing, both in 1974. This wave of closings was due to the schools being fiscal drains on the parent hospitals, as well as the changing educational standards professional nursing organizations championed, including the baccalaureate degree as the best entry-level credential for nurses. And so it was, but only briefly. The first class was admitted to the program in fall 1969, along with a sophomore group that had started at Sinai, and a graduation ceremony was held in 1972 for thirteen students. However, the two institutions could not work out long-term arrangements and so the relationship was terminated by 1974.

And so it was, but only briefly. The first class was admitted to the program in fall 1969, along with a sophomore group that had started at Sinai, and a graduation ceremony was held in 1972 for thirteen students. However, the two institutions could not work out long-term arrangements and so the relationship was terminated by 1974.