This is the second in a series, The Mount Sinai Doctor, that are adapted from the thorough biographical entries located in our Archives catalog, information gathered from This House of Noble Deeds: The Mount Sinai Hospital, 1852-2002, and the unpublished unique material stewarded in our Archives.

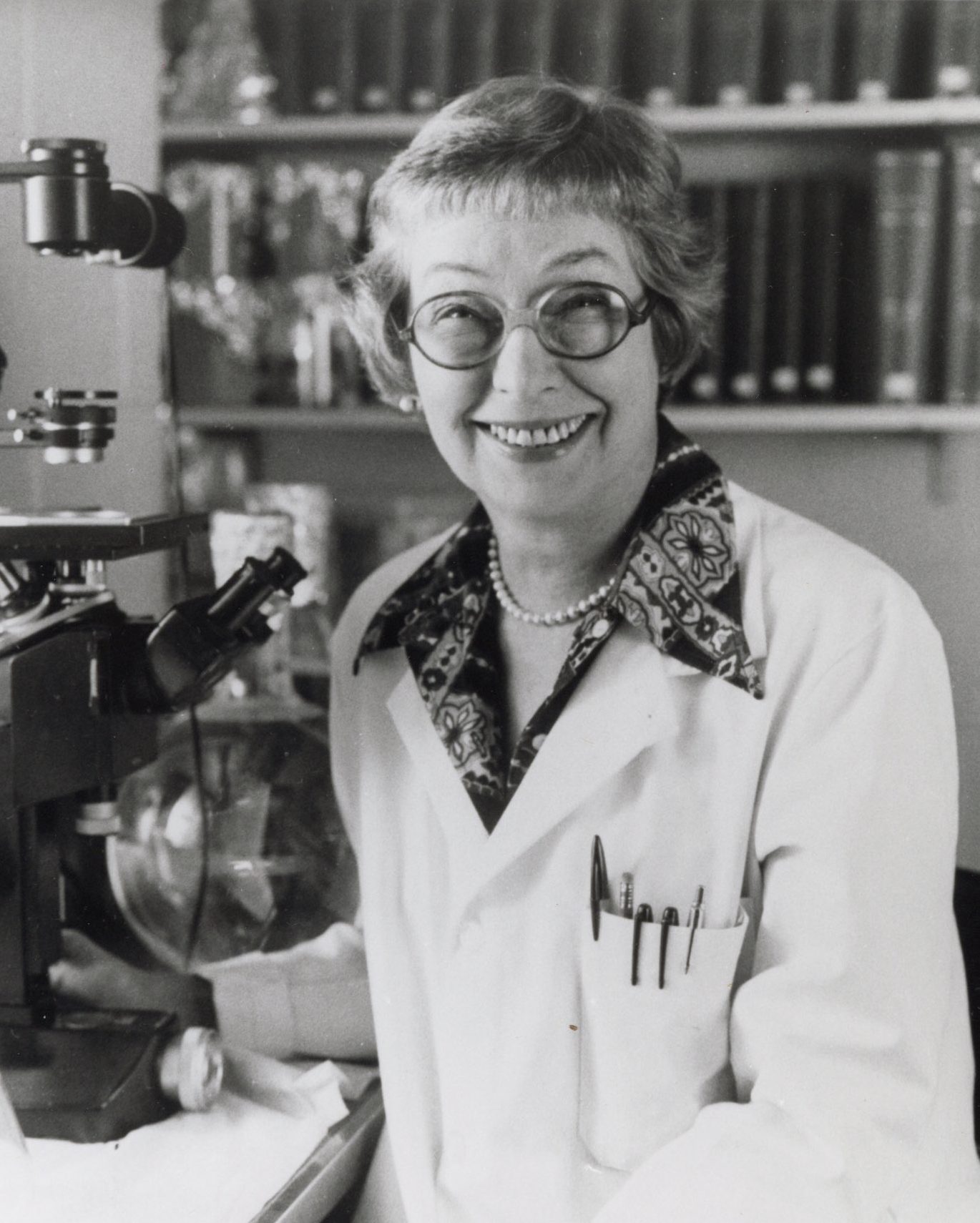

Hailed as a gifted scientist, noted microbiologist, renowned virologist, and exceptional researcher, Dr. Charlotte Friend’s contributions to the field of cancer research continue to be foundational. She was the first and only female full Professor appointed to the Mount Sinai School of Medicine when the faculty was formed in 1966. Among many accomplishments, she is most celebrated for (1) discovering the Friend leukemia virus, proving that viruses can be the cause of some types of cancers, and (2) demonstrating that cancer cells can be stopped from multiplying and revert to being normal cells through a chemical treatment by a compound called dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Early Life

Her important contributions to the study of cancer began and ended in New York, a city she loved. She was born March 11, 1921 on Houston Street to Russian immigrant parents. After her father passed away, her mother moved Charlotte and her three siblings to the Bronx. Growing up in the Great Depression, her family received “home relief” from the city to survive. She received a bachelor’s degree from Hunter College in 1944. During World War II, she entered the Navy where she was assigned to help direct a hematology laboratory in California. After leaving the Navy in 1946 and with the support of the G.I. Bill, she began graduate work in microbiology at Yale University. By the time she received her doctorate in 1950, Dr. Friend already had a position in the laboratory of Dr. Alice Moore at the then Sloan-Kettering Institute in New York City.

Career

In 1956, Dr. Friend gave a paper at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research in which she stated that she had discovered a virus that caused a leukemia-like disorder in newborn mice. She was roundly criticized for bringing up what was considered to be the false belief that viruses could cause cancer. Not only was her discovery correct and a watershed moment, the tide of change finally turned in the face of mounting evidence. Dr. Friend spent the following years investigating different aspects of the virus, as did many other researchers.

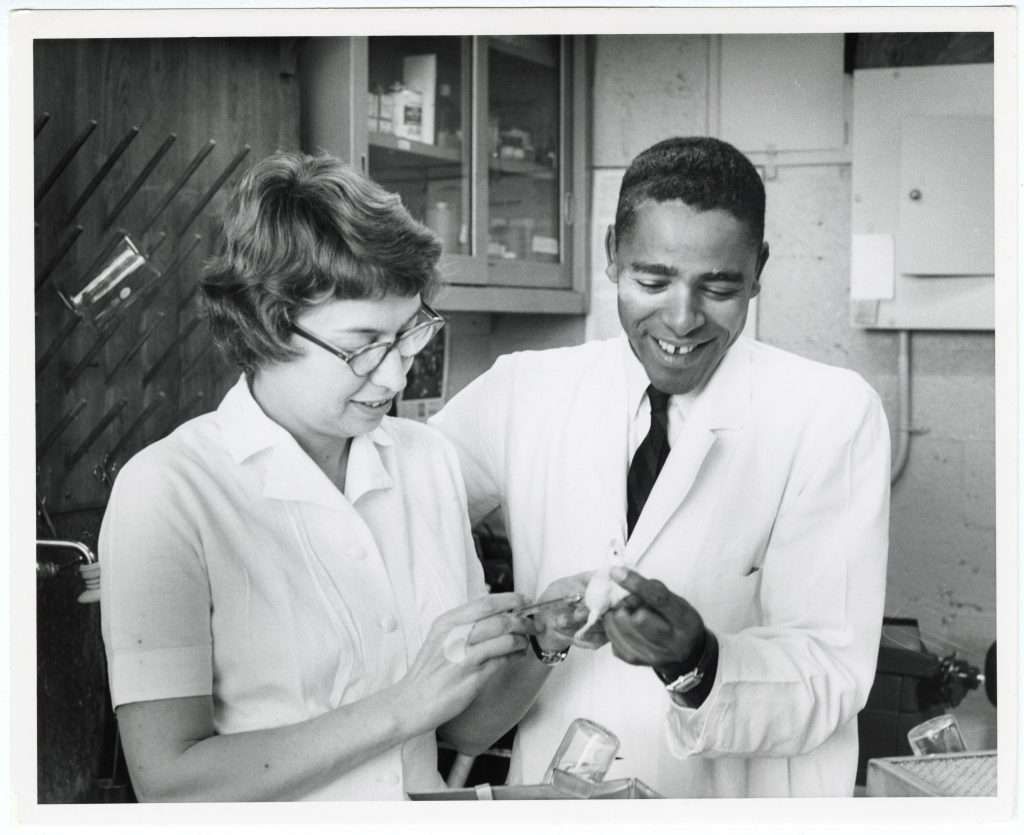

In 1966, Dr. Friend left Sloan-Kettering to become the first Director of the Center for Experimental Cell Biology and a Professor at the still developing Mount Sinai School of Medicine. She also was a Professor in the Graduate School of Biological Sciences. At Mount Sinai, she established her own laboratory that in 1967 was endowed as the Mollie B. Roth Laboratory. Still, there was an unending struggle to find the funding to keep the lab well-staffed and well equipped, a situation that got harder as federal funding began to shrink in the 1970s. The decline in federal funds for basic research led Dr. Friend to write several protest letters to congressmen and others in power. This was a tactic that she often took when a subject that mattered to her was at issue. During her time at Mount Sinai she “helped shape the educational and research philosophy” of the new School of Medicine. Dr. Nathan Kase, a former Dean of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, said “Her presence was a major factor in establishing at the fledgling medical school a balance between emphasis on clinical care and on basic science research.” Dr. Terry Ann Krulwich, former Dean of the Mount Sinai Graduate School of Biological Sciences, noted that Dr. Friend had “a special feeling for students and the larger academic community.”1 To read more about the Mount Sinai School of Medicine’s early days, read about the first Deans, Doris Siegel (the first woman named to an endowed chair), and the opening day.

Advocacy, Service, & Awards

Her discovery of the Friend leukemia virus established her reputation very early in her career. Perhaps because of this, she felt that she herself was not held back by being a woman, except for some wage discrimination. Still, she believed that science truly had been a man’s world and that it would take conscious and steady efforts by women to change this. For her part, this involved nominating women to positions of authority in organizations; suggesting women speakers for programs; speaking out about women’s issues; serving as a role model to young women from grade school to graduate school; and ultimately, by taking time from her own lab to serve in prominent positions in professional associations.

One example of her advocacy was in 1979 when she confronted Francis Crick to adequately recognize that Rosalind Franklin was close to solving DNA structure on her own. He had published an article in The Sciences which he criticized her character as “brisk”, “oversensitive”, and “too stubborn.”2 Attacks on character aside, Dr. Friend wrote to him and pointed out that he “never accepted her as a first-class scientist.”3 Crick replied, “I now see what the trouble is. You apparently believe Rosalind was a first rate scientist. I think she was a good experimentalist but certainly not of the first class… What I object to is the artificial inflation of her reputation by women who do not fully understand her work and often did not know her personally.”4 He only conceded by citing “in particular Dr. Aaron Klug” (a man) as having made the argument to him.5 To this Dr. Friend published a letter to the editors, commenting, “Methinks the gentleman doth protest too much.”6 Her humorous response to sexist discrimination shows Dr. Friend’s perseverance and that she likely frequently employed this strategy to stand up for herself and others when faced with such reprehensible behavior.

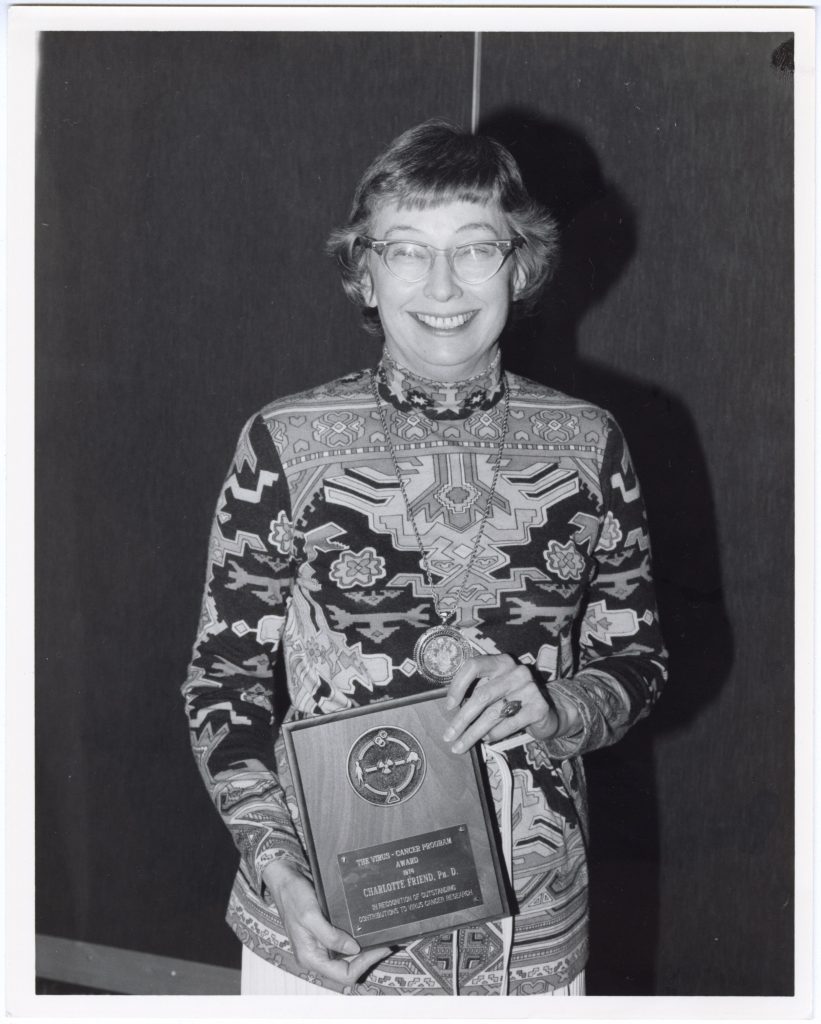

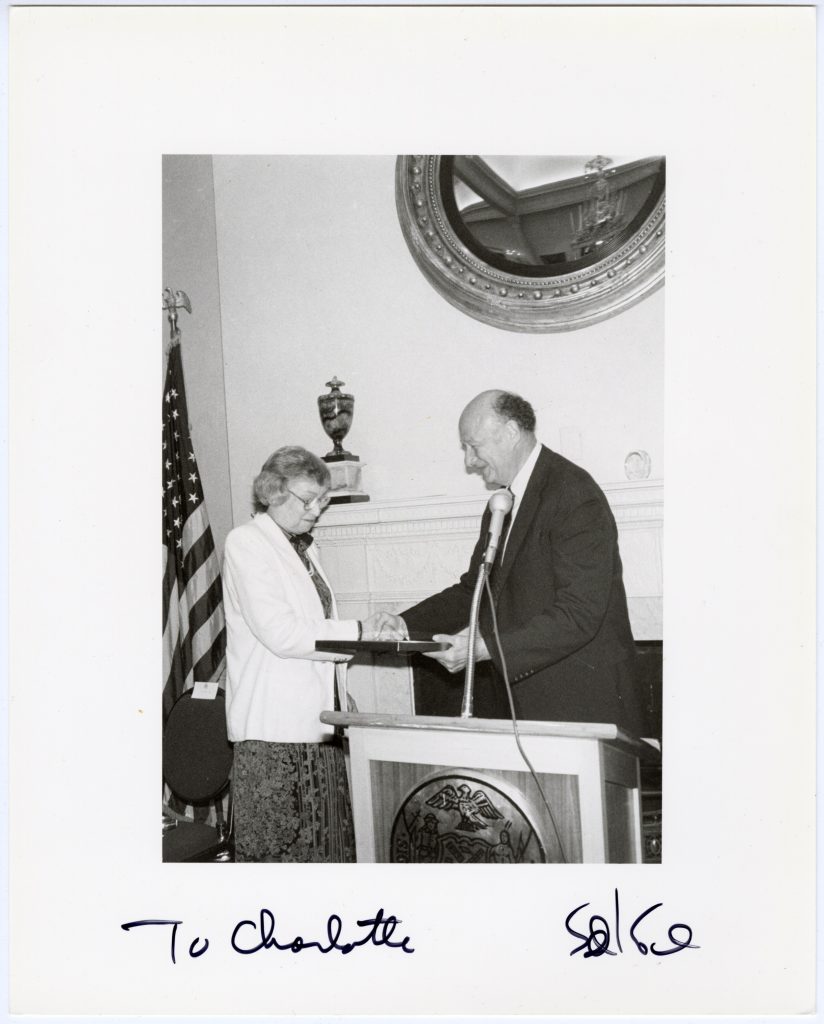

In the 1970s, when many associations ‘discovered’ their female members, Dr. Friend was asked to assume leadership roles in several organizations including: chairman of the Gordon Conference (1973); member of the Board of Directors (1973-76) and president (1976) of the American Association for Cancer Research; president of the Harvey Society (1978/79); and president of the New York Academy of Sciences (1978).

Accomplishments, Collaboration, & Recognition

Dr. Friend’s papers are in the Aufses Archives’ collection and provide insight into the world of cancer research during an important era, one which Dr. Friend herself helped propel. This was the time, starting in the 1950s, when scientists gradually turned to an acceptance of viruses as cancer causing agents in humans. The evolution of the field may be traced through the programs of conferences that Dr. Friend attended, the journal articles that she reviewed, as well as through correspondence and her own research. These papers also show the intimacy of the cancer research community itself, at least at the level at which Dr. Friend operated. Her papers provide information on women’s role in science.

She wrote about many things, including support for Israel, against anti-abortion measures, and in defense of women’s rights. In 1971, Dr. Friend published another landmark paper, this one titled “Hemoglobin synthesis in murine virus-induced leukemic cells in vitro: Stimulation of erythroid differentiation by dimethyl sulfoxide.” The co-authors were William Scher, J.G. Holland, and Toru Sato. This paper described research on leukemia cells that had been made to differentiate, or take another step in the maturation process to become erythroid cells, thus stopping their cancer-like multiplication. Research continues today by many others in the field trying to make this a reality in cancer care.

A frequent collaborator with other scientists, she often took part in international research efforts. Dr. Friend loved to travel and formed many long-term friendships with colleagues in Europe. Her sabbatical years (1963 and 1975) were spent working in laboratories in Australia, Israel, France, and Italy. She attended many international meetings and was very active in various associations and in outside professional activities, such as grant reviewing and serving on editorial boards and advisory councils.

In all, she published 163 papers, 70 of which she wrote by herself or with one other author. She won several awards, including: the Alfred P. Sloan Award in Cancer Research in 1954, 1957, and 1962; the Jacobi Medallion in 1984; first-ever Mayor’s award in Science and Technology in 1985; and an Honorary Doctor of Science from Brandeis University in 1986. Throughout her career, she was consistently generous in distributing her virus (FLV) and her cells (FELC) to others who wanted to work with them. Dr. Friend remains outstanding for having made two major contributions during her career.

Although diagnosed with lymphoma on her 60th birthday in 1981, she told few of her illness. She continued to go about her work with all the energy she had, writing grants, serving on many committees, and working in the lab. Charlotte Friend died in January 1987.

Works Cited

- 1.Schmeck Jr. HM. CHARLOTTE FRIEND DIES AT 65; RESEARCHED CANCER VIRUSES. The New York Times. January 16, 1987:18.

- 2.Crick F. How to Live with a Golden Helix. The Sciences. 1979;19:6-9. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/101584582X462

- 3.Friend C. [Letter to Francis Crick]. The Francis Crick Papers. Published September 11, 1979. Accessed March 28, 2023. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/101584582X227

- 4.Crick F. [Letter to Charlotte Friend]. The Francis Crick Papers. Published September 18, 1979. Accessed March 28, 2023. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/101584582X367

- 5.Crick F. [Letter to the Editor of The Sciences]. The Francis Crick Papers. Published October 2, 1979. Accessed March 28, 2023. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/101584582X225

- 6.Friend C. [Letter to the Editor of The Sciences]. The Francis Crick Papers. Published December 1979. Accessed March 28, 2023. http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101584582X463

This post was authored by J.E. Molly Seegers, based upon the biographical note written by Barbara Niss.