Jun 24, 2020

The trials of life can crush one’s spirit or force one to overcome and create something exceptional out of the rubble. Mary Breckinridge, a 1910 St. Luke’s Hospital School of Nursing alumna, is a fine example of later. Born into a Kentucky family of influence and means, Breckinridge was well educated and well-traveled. She was married in 1904 and widowed by 1906, at age 26. She then completed St. Luke’s nursing program and worked teaching French and hygiene in an Arkansas women’s college. In 1912, she married the president of that school and had two children with him, but her daughter was premature and did not survive; her son died suddenly two years later at age four.

Additional struggles broke the marriage beyond repair and she left her husband in 1918 and worked as a public health nurse while awaiting a posting with the American Red Cross in France. She arrived there after the armistice of WW I and helped to initiate a program to provide food and medical assistance for children, nursing mothers, and pregnant women. While in France, she also spent time in England, observing the conditions of children and mothers there, and became convinced that American women in rural areas would benefit from the help of trained midwives. Ad educational visit to Scotland demonstrated how to provide medical care to a dispersed population.

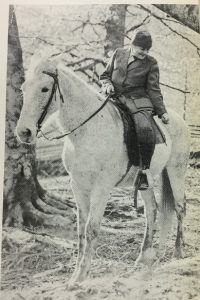

Returning to the United States, she relocated to Leslie County, Kentucky, which had the highest maternal mortality rate in the country. Here Breckinridge, pictured left, introduced nurse-midwives into the region with the founding of The Frontier Nursing Service in 1925, eventually bringing maternal and neonatal death rates down well below the national average. In 1929, The Frontier Nursing Service staff started the American Association of Nurse-Midwives, a precursor of the American College of Nurse-Midwives, and the first American school of midwifery in New York in 1932. Mary Breckinridge served as director of the FNS until her death on May 16, 1965.

Jun 11, 2020

This is a continuation of a guest blog post by Colleen Stapleton. Colleen is a Patient Navigator with the Liver Education and Action Program (LEAP) at Mount Sinai, where she works to improve linkage to care for patients living with Hepatitis C. You can read the original post here.

Scanning

My first day scanning, the team and I addressed the technology involved in making our Mount Sinai News collection available online. I learned about the scanning specifications to best archive our newsletters digitally. These specifications included 300 dpi (dots per inch), “do not scale,” and others particular to our scanner.

I also learned how to navigate the interesting physical space of the IT office, where the scanner was placed in a small kitchenette. Since I was scanning during lunchtime, I saw a few lunches popped in and out of the microwave. I learned that I could go ahead and put the precious paper newsletters on a non-descript plastic yellow barrel drum object, but under no circumstances should papers be placed on the potentially wet nearby water cooler!

Starting with November of 1958, I began electronically piecing together our carefully preserved collection of Mount Sinai Hospital history.

Folding Paper

Gently unfolding each 60-odd year old newsprint was both a physical challenge and delight. I soon fell into the rhythm of scanning the first page, then the second, then switching to scanning the inserted third and fourth pages. Since the newsletters are not stapled, in total I would carefully reverse the seams of two folded pages, then finish up with the back section of the first folded page.

After a few sessions, I noticed that the newsletters were getting considerably longer – some included 12 pages! This 12-page spread would include a total of three seams, and so unfolding and folding would come to resemble the act of taking apart and putting back together a precious Russian doll.

Troubleshooting

My first day at the scanner I became aware that any file containing more than five pages could not be sent via email to our Archives team account. I made the decision at this time to scan four pages at a time, sending the files to the Archives account in pieces. I soon saw the stacks of newsletters flowing from the “un-scanned” to the “scanned” pile.

After each session I would return to my desk and make sure every issue was represented and the scan quality was good. The various parts of each issue were then virtually ‘stitched’ together. Though some months came and went without Mount Sinai Hospital News editions, each newsletter is marked chronologically with issue numbers.

The first Science News insert of the new Mount Sinai School of Medicine

One of my favorite developments in my scanning came with the advent of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Science News, an insert that was developed as the medical school was founded and produced more and more significant scientific discoveries. There was also the Mount Sinai Medical Center News title change in November-December 1969 to correspond with the newly built school of medicine. The history of Mount Sinai was expanding before my eyes and I had to ensure my metadata reflected these changes!

Moving Forward with Metadata

After scanning part I of the MSH News archive, the team met with the Aufses Archives’ Digital Archivist to clarify our strategy moving forward. We confirmed our goal of making the Adobe PDFs of the News pages available online, creating a digital index of all MSH News electronic files, as well as providing readers with a search function powered by Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to more easily search the newsletter files.

We identified questions to the tune of “How should we put the PDF files online?” and “how can we most easily create an index to the publication?” We ultimately decided to OCR the PDF documents with Adobe and then dump the words into a database program used by the Aufses Archives called DBTextworks. We started with a few pilot issue files and we identified any necessary metadata fields for our project.

So began an exciting new phase: cleaning and inputting metadata. Unfortunately, this was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to stay home, and we have not been able to continue the scanning. However, the work continues with the efforts of a fantastic new summer intern working remotely — soon all of the scanned issues will be described and searchable.

Stay tuned for more blog installments exploring this digitization project along with coverage of the many unique historical Sinai snapshots found in the MSH News!

Jun 4, 2020

An update to this blog post can be found here.

Founded in 1892, the early history of Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital was decorated with a series of success stories in the treatment of disease. Against the background of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, then affected by poverty, close living quarters, and dangerous working conditions, its residents, largely recent Jewish immigrants, were made vulnerable to many of the contagious diseases of that era. In its first years, Beth Israel contributed research to combat the typhoid epidemic of 1906-1907, established an after-care clinic to children affected by the 1916 polio epidemic, and is credited with finding the cure for trachoma, which had previously been a cause to turn away new immigrants at Ellis Island.

Only twenty-five years after Beth Israel’s opening, the United States was embroiled in the first World War. The Hospital encouraged its medical staff to join the Medical Reserve Corps, with approximately half of its doctors signing up. The Hospital had also encouraged its nurses, physicians and other staff to join the war effort.

This left Beth Israel in a precarious position when the 1918 Influenza epidemic reached New York City. Being chronically understaffed, Beth Israel’s Medical Board contacted the Department of Health for advice. The response was simply: “There is nothing to advise except the use of gauze masks which did not always prevent the disease.” In November 1918, the Hospital eliminated visiting hours, curtailed teaching hours, and turned the Male Medical Ward over to the Department of Health to use as an isolation facility for the pandemic. (The DOH never used the facility because they were similarly understaffed.)

Female ward of Beth Israel Hospital, Jefferson and Cherry Street, circa 1910

Ultimately, Beth Israel was only able to admit twenty-nine influenza patients. (Update: This number is disputed in other sources.) Seven members of the House Staff were awarded $25 (approximately $500 today) for “self-sacrificing services performed” and the Hospital offered special incentive pay to doctors and nurses to help combat the fact that they were understaffed.

Despite the limited patient intake, Beth Israel’s contributions to the 1918 flu pandemic were still impactful. In December 1918, Superintendent of the Hospital, Louis J. Frank, contacted Presidents Roosevelt and Taft to encourage universal nursing training in the education of women, likely in response to the chronic under-staffing at this time. By January 1919, many of the patients in the Hospital were admitted for “post-influenzal complications” leading to the care of many affected by the pandemic.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

May 28, 2020

Mount Sinai physicians have a long tradition of making important contributions to the scientific literature. A good example is the following case from the 1910s, when typhus swept the world, killing thousands of people.

In 1910, Nathan Brill, MD, a doctor in the Department of Medicine, published a description of what he thought was the endemic form of typhus; this became known as Brill’s Disease. (Later Hans Zinsser showed that it was not endemic, but a mild recrudescent form of epidemic typhus and the name was changed to Brill-Zinsser disease.) In 1913, Harry Plotz, MD, an intern working in Mount Sinai‘s Pathology Laboratory, believed that he had discovered an organism that caused typhus. He published a Letter in JAMA in 1914 outlining his research.

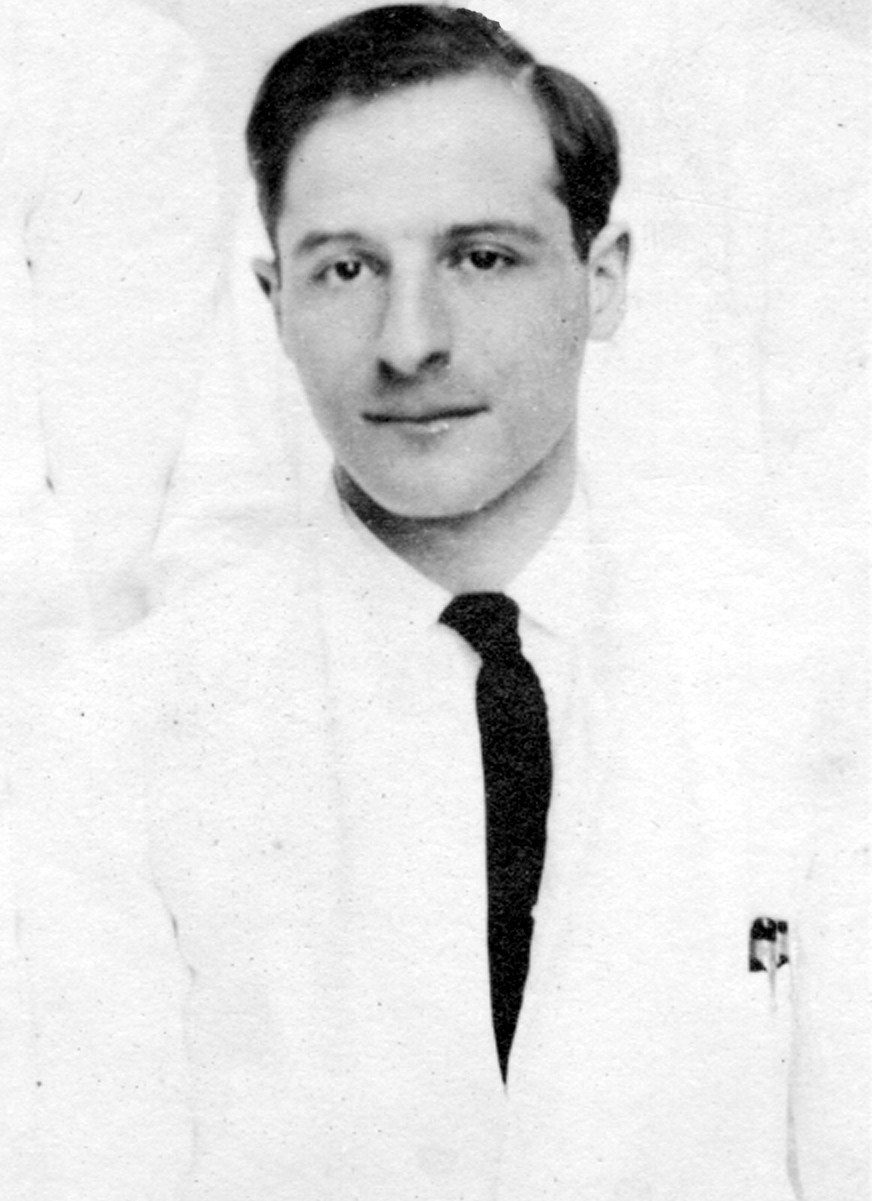

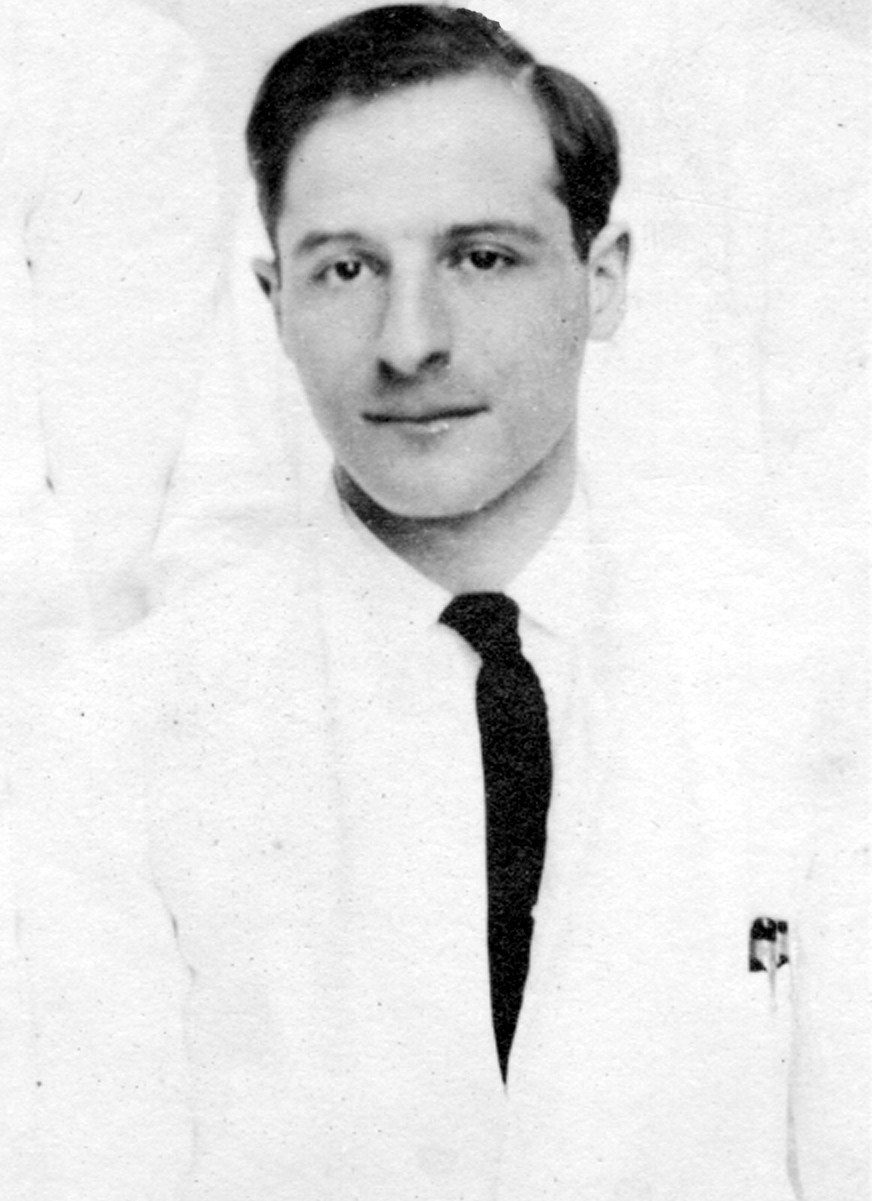

Harry Plotz, MD as a Mount Sinai intern in 1915

Since this was such an important public health problem, in 1915, Mount Sinai’s Trustees took the unusual step of agreeing to fund a trip to gather blood specimens in the Balkans, where there was a typhus outbreak – and the early stages of World War I. As noted in Wikipedia: “disease ravaged the armies of the Eastern Front, where over 150,000 died in Serbia alone. Fatalities were generally between 10% and 40% of those infected and the disease was a major cause of death for those nursing the sick.”

The research results of this trip were described by the physicians Harry Plotz and George Baehr in a 1917 paper in the Journal of Infectious Diseases. The details of the trip itself are described in the 1916 Annual Report of The Mount Sinai Hospital This narrative also describes an additional trip by Dr. Peter Olitzky to Mexico, also funded by Mount Sinai, when the researchers in Europe were taken prisoner by the Austro-Hungarian government. This lengthy quote provides the Trustee President of Mount Sinai’s description of the events of 1915-16:

In pursuance of my remarks of last year in regard to the typhus expedition to Serbia, I wish to state that Drs. George Baehr and Harry Plotz after many difficulties established a laboratory at Belgrade in a hospital directed by the American Red Cross. Thirty-six hours before the bombardment of Belgrade, they left for Uskub and there set up a laboratory in the Lady Paget Hospital, and shortly thereafter the town was occupied by the Bulgarians. Very soon afterwards they were invited by the Bulgarian and Austrian Governments to work under their auspices. They then left for Sofia and afterwards went to Vienna, Lemberg and into Russia….

Because of the fact that Drs. Baehr and Plotz during the first six months of their stay in Europe, practically did not come in contact with typhus fever, it was considered important to send a second expedition into Mexico to determine the cause of the Mexican typhus fever, and to carry on other work which at that time we were not sure could be carried on in Europe. The second expedition consisted of Drs. Peter K. Olitzky and Bernard S. Denzer, accompanied by Mr. Irving Brout, a laboratory helper, and the expedition was under the guidance and care of Dr. Carlos E. Husk, a prominent surgeon attached to the staff of the American Smelting & Refining Co. The expenses of the expedition were defrayed in part by Trustees of the Mount Sinai Hospital and in part by the American Smelting & Refining Co.

It was first decided to go to Aguascalientes, but after the expedition reached Matehuala it was determined to remain there, as even at that distance from the border the danger, because of dis- turbances of international conditions, was very great. Early in March, because of the increasing danger in which the men were placed, they were requested to return. The members of the expedition did not, however, leave, because Dr. Olitzky had been stricken with a severe attack of typhus fever. Very shortly thereafter, the plants of the American Smelting & Refining Co. throughout Mexico were closed down, and Dr. Olitzky had to be removed to Laredo, Texas. Just before the departure Dr. Husk, who had been of the greatest aid in the accomplishment of a remarkable piece of work within four weeks, also fell ill of typhus fever, and was brought into Laredo in a very serious condition. Dr. Olitzky after going through a most dangerous attack of the disease, recovered, but unfortunately it proved impossible to save Dr. Husk’s life.

During the course of this expedition the same germ was found in the typhus fever cases in Mexico as had been found in New York and as was found by the members of the European expedition in Serbia, Bulgaria, Austria and Russia. Apart from that, the typhus germ was cultivated repeatedly from lice, which have in recent years been considered the agent in transferring typhus fever from one person to another. Some further scientific studies were made, and vaccination done on a rather large scale. The results of the vaccination cannot be determined at the present time because of the unsettled conditions in Mexico.

In the end, no successful vaccine has been developed for typhus, but antibiotics and public health measures have made it a treatable, rarely fatal disease in the U.S.

The story of typhus and Mount Sinai is important because it shows the institution’s commitment to research and developing new treatments during times of crisis. As shown here, this commitment is not solely from the medical and scientific staff, but also from the Trustees and supporters of Mount Sinai. When times are dire, as in today’s COVID-19 pandemic, Sinai finds a way to enable the work to get done to advance medical knowledge and improve the treatment of patients.

May 12, 2020

This year the world marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Florence Nightingale (1820-1910.) Her name is known around the world and nurses everywhere enjoy the fruits of her labors today. She lived a long time ago in a very different world, but she enunciated the basic philosophy of modern nursing, and introduced statistics into the study of disease.

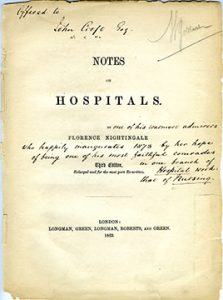

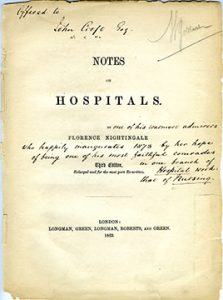

The Aufses Archives has copies of two of Miss Nightingale’s books: Notes on Nursing and Notes on Hospitals. The Mount Sinai Hospital School of Nursing, which existed from 1881-1971, had a small collection of Nightingale letters that they had gathered over the years. Some of these were given to the Columbia University School of Nursing in 1953, as shown in the image below.

From the Aufses Archives

Hospitals, schools of nursing, archives, and history of medicine collections will be marking the 200th anniversary of Florence Nightingale this year with celebrations, blog posts, exhibits and lectures. Here are links to just a few of those celebrations going on this year:

Nightingale: Lady and Legend at the National Library of Medicine: https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2020/05/12/nightingale-lady-and-legend/ This includes this note on sources: The National Library of Medicine’s holdings of Nightingale materials are (unsurprisingly) extensive, with over seventy printed titles and editions. In addition, the Library holds a group of Nightingale letters written between 1845 and 1878, all of which may be read as part of the Florence Nightingale Digitization Project, and a copy of an oral history interview conducted by M. Adelaide Nutting (herself a giant in the history of nursing) in 1890. A transcript is available at http://oculus.nlm.nih.gov/2935116r.

A blog post on the University of Maryland, Baltimore School of Nursing ties to Nightingale: https://www2.hshsl.umaryland.edu/hslupdates/?p=4177

A blog post at the UCLA Library about the Elmer Belt FN Collection and other Nightingaleiana we have and use: https://www.library.ucla.edu/blog/special/2020/05/11/happy-birthday-florence-nightingale

Finally, there is a special exhibit at the Florence Nightingale Museum in London called Nightingale in 200 Objects, People & Places https://www.florence-nightingale.co.uk/200objects/ Sadly, the Museum is closed due to the pandemic and is struggling financially. As they note:

Nursing, washing your hands and evidence based-healthcare, pioneered by Florence Nightingale, have become more important than ever before and we’re calling upon our friends and supporters to help us preserve her story and legacy.