Apr 7, 2022

Woman’s Hospital (1855-1952) is a unique institution in the history of American medicine, in several ways. It has claimed to be the first hospital in the world devoted exclusively to “the problems of medicine peculiar to women.” Founded by a group of well-to-do women in NYC, in conjunction with Dr. J. Marion Sims, this group formed the Women’s Hospital Association, and ran the Hospital themselves for the first several years. It was re-organized and re-chartered as the Woman’s Hospital in the State of New York in 1857, making the drastic change of introducing an all-male Board of Governors, who ran the top-level business of the organization. Considering the limits of female power in 1857 and connections in business and finance needed at that time in order to run a growing medical facility, it makes some sense. (1)

Women did, however, continue to run the majority of the daily business of the Hospital. In the 1880s several of the ‘Lady Managers’ were invited to join the Board of Governors by necessity, to fill several slots that had gone unfilled for a prolonged time. It was a successful experiment and made permanent after about a year, re-creating the Board almost equally by gender. What is a bit odd, considering the strong presence of women in the leadership, is that it took until 1918 for a woman to break into the medical end of the work. However, the woman who did it was as unique and unusual as the Hospital for which she worked.

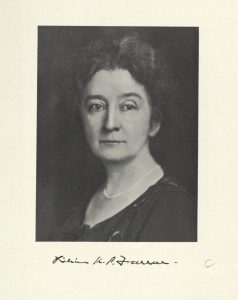

Lillian Keturah Pond Farrar was born in Newton Center, Massachusetts in December 1871 to Jefferson Clinton Farrar Jr., and Sarah D. Pond. (2) She earned her BA at Boston University, and completed her medical education at the Cornell University Medical College. Records there indicate that prior to enrolling she took medical classes at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children between 1896 and 1899. She graduated from Cornell in 1900 at age 29, and returned to the New York Infirmary to take her internship. (3) After that, she spent several years (1901-1904) training in Paris and in Vienna, visiting medical clinics in Paris, Berlin, London, Stockholm, and Rome as well, much like any male physician of that time might do. (4)

Lillian Keturah Pond Farrar was born in Newton Center, Massachusetts in December 1871 to Jefferson Clinton Farrar Jr., and Sarah D. Pond. (2) She earned her BA at Boston University, and completed her medical education at the Cornell University Medical College. Records there indicate that prior to enrolling she took medical classes at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children between 1896 and 1899. She graduated from Cornell in 1900 at age 29, and returned to the New York Infirmary to take her internship. (3) After that, she spent several years (1901-1904) training in Paris and in Vienna, visiting medical clinics in Paris, Berlin, London, Stockholm, and Rome as well, much like any male physician of that time might do. (4)

After her European training was completed, our information about Dr. Farrar jumps to 1918. That year Lilian K.P. Farrar, MD, age 47, became a Junior Attending Surgeon, the first woman physician appointed at Woman’s Hospital. She became an Attending Surgeon in 1927 and Consulting Surgeon in 1935 at age 64. (5)

Relatively unknown today, Dr. Farrar was active in the broader medical community during her working life. She was a woman of firsts: the first woman to serve as an Assistant Professor in Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Cornell University Medical College from 1918 until 1953 (ages 47- 82) and the first woman physician appointed Chief of Clinics (gynecology) there as well. She was the first woman elected as a Fellow of the American Gynecological Society in 1921, and the only woman in the Society for fifty years, as another woman wasn’t welcomed in until 1971 (6). She was the first woman to serve as a Governor of the American College of Surgeons, serving multiple terms between 1925 and 1937. Additionally, she was the first – and only – woman to be a ‘founding Diplomate’ of the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (1930). Her body of articles, published between 1917 and 1937, indicate that she was an accomplished gynecological surgeon, even collaborating with a colleague on perfecting irradiation techniques for treating gynecological cancers. (7)

Outside of professional accomplishments, Farrar, who remained single throughout her life, numbered among the social elite of her time. She is listed in both the New York Social Blue Book for 1930 (8), and the Register of the National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York 1893-1926. (9) The Society requires members be direct descendants of someone, or in her case, ten of them, who “lived in the American colony and rendered it service before July 5, 1776.” (10) Farrar supported the Woman’s Suffrage movement and fostered the acceptance of women as interns at Bellevue Hospital, New York, in 1914 and at Woman’s Hospital in 1920. (11)

Another gap in our information about Dr. Farrar exists between 1953 and her death in the Lake Placid Memorial Hospital on June 22, 1962, attributed to arteriosclerotic heart disease (12), at the age of 90. (13) She is buried in Newton Center, Massachusetts.

Sources:

1. Annual Reports of Woman’s Hospital, 1855; 1857; 1918; 1920

2. Family Search website listing: https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/MQQX-JLV/lillian-keturah-pond-farrar-1871-1962

3. Cornell University Medical College Students Register 1898-1907. NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine Medical Center Archives.

4. Dr. Lillian K.P. Farrar. Medical Woman’s Journal (vol. XLIII, page 190, July 1936).

5. Obituary. The Times Newsletter of Woman’s Hospital, Dec 1962, Vol 14, #2 p.11

6. “Gender Ideology in the Rise of Obstetrics.” Naoko ONO. The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 17 (2006)

7. Women in Medicine website: http://obgynhistory.net/miscwomandocs.html

8. NY Social Blue Book: http://bklyn-genealogy-info.stevemorse.org/Directory/Blue/1930.BlueF.html

9. Register of the National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York, 1893-1926 https://www.google.com/books/edition/Register_of_the_National_Society_of_Colo/TdBKAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=the+Register+of+the+National+Society+of+Colonial+Dames+in+the+State+of+New+York.+1893-1926&pg=PA3&printsec=frontcover

10. The National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York website membership inquiries page: https://www.nscdny.org/membership-inquires

11. Dr. Lillian K.P. Farrar. Medical Woman’s Journal (vol. XLIII, page 190, July 1936).

12. Unidentified clipping, from the Elizabeth Bass Collection on Women in Medicine, Rudolph Matas Medical Library, Tulane University Medical Center, LA. https://library.tulane.edu/sites/default/files/media-files/matas/matas_collections_bassindex2014_01.pdf

13. Obituary. The Times Newsletter of Woman’s Hospital, Dec 1962, Vol 14, #2 p.11

Authored by Michala Biondi, Associate Archivist

Mar 16, 2022

An interactive map of Beth Israel historical locations is available here. See the Building Beth Israel series for more information about the history of MSBI.

Mount Sinai Brooklyn is one of the more recent New York hospitals to join the Mount Sinai Health System. Prior to its most recent incarnation, the hospital dates to the 1950s and was a long-time division of Mount Sinai Beth Israel.

Prior to the 1950s, the location was a series of interlocking lots. In 1953, the parcel was created at 3201 Kings Highway for Samuel Berson, MD, a specialist in allergy and immunology, to create a nursing home there. Though the exact timing is unknown, the nursing home was converted into Kings Highway Hospital shortly after with 212 beds. In 1980, King’s Highway Hospital opened its North wing, without an increase in the number of beds. As a small, private, community hospital, not much documentation has survived from those years.

On July 11, 1994, a special meeting of the Beth Israel Medical Center Board of Trustees passed a resolution “that the Medical Center proceed to negotiate the acquisition of Kings Highway Hospital.” By adding Kings Highway to the existing Petrie and North divisions, “on the basis of total admissions per year, the acquisition makes Beth Israel the largest voluntary hospital in New York City and one of the largest in the United States.”

The period following Beth Israel’s acquisition marked a time of rapid renovation and development at the Kings Highway Division. This included renovations at the Surgi-Center (1996); the introduction of three-bed inpatient Acute Dialysis Unit (November 1996); an expansion of the Russian Health Service and other Russian language amenities (1998); and an expansion of the emergency room from six to seventeen treatment slots (Summer 1998). Perhaps most significant was the groundbreaking for the new building starting in May 1998, which included underground parking, a new emergency department, ICU, and five new operating rooms. The new facility, called the Acute Care Pavilion, was built on what was previously the hospital parking lot, and opened in May 2000.

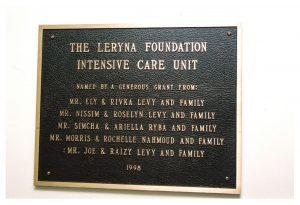

These renovations and expansions continued with significant investment from donors. In February 1997, Beth Israel Kings Highway Division in Brooklyn received a $150,000 gift from the Leryna Foundation, the family foundation of Ely Levy, an electronics distributor and leader of the Sephardic community in Brooklyn. The gift doubled the number of beds in the ICU from six to twelve. In 1997, the Greater Montreal Convention and Tourism Bureau named Kings Highway Hospital as the beneficiary of proceeds for its production of Robert Lepage’s The Seven Streams of the River Ota at the Next Wave Festival of the Brooklyn Academy of Music. And finally, in December 2002, the Louis Mintz Family Waiting Room in Critical Care Unit was endowed.

With Beth Israel’s merger into the Mount Sinai Health System, the Kings Highway Division was renamed Mount Sinai Beth Israel Brooklyn in January 2014, and then was shortened to Mount Sinai Brooklyn in May 2015. It remains part of the Mount Sinai Health System today.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser with research credit to Nicholas Webb

Mar 2, 2022

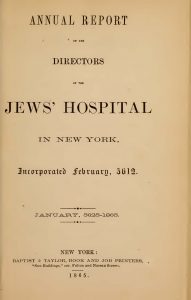

Title page of the 1864 Annual Report of the Directors of Jews’ Hospital in New York

Mount Sinai Hospital’s predecessor institution, Jews’ Hospital in New York, was established in 1852, opened in 1855, and initially admitted only people of the Jewish faith and accident victims. A mere twelve years later in 1864 the Board of Directors decided to open the hospital to all, regardless of faith. Then in 1866, to reflect this new policy, the institution changed its name to Mount Sinai Hospital. But why did the Hospital become non-sectarian? At a point in time when many Hospitals founded by other creeds continued their religious affiliations, Jews’ Hospital broke with tradition. It might come as a surprise that the decision to treat people regardless of faith was influenced by the Civil War and the New York City Draft Riots of 1863, one of the “bloodiest race riots in American history.” The profound devastation wrought upon Black people during the gruesome riots shaped New York as we know it today and had a profound impact on the early days of our health system.

In the introduction to The First Hundred Years of The Mount Sinai Hospital of New York, 1852-1952, the authors posit that Jews’ Hospital, as it was in the geographic center of the riots, was “the asylum for their dead and injured. An eventual result for the Hospital was its adoption of the nonsectarianism which has been its policy ever since.” Which begs the question: who did they treat, and did treating victims of the riots actually persuade the Hospital’s Leadership to change its policy? To answer that question, we need to know what occurred in New York City during the years leading up to the 1864 decision. The United States was in the thick of the Civil War which raged from 1861 to 1865. New York City, while positioned as a northern city allied with the Union, was in fact quite a conservative city due to its financial connections to the south.

Section 1869 map of New York showing the Jews’ Hospital in blue rectangle (map courtesy of Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library)

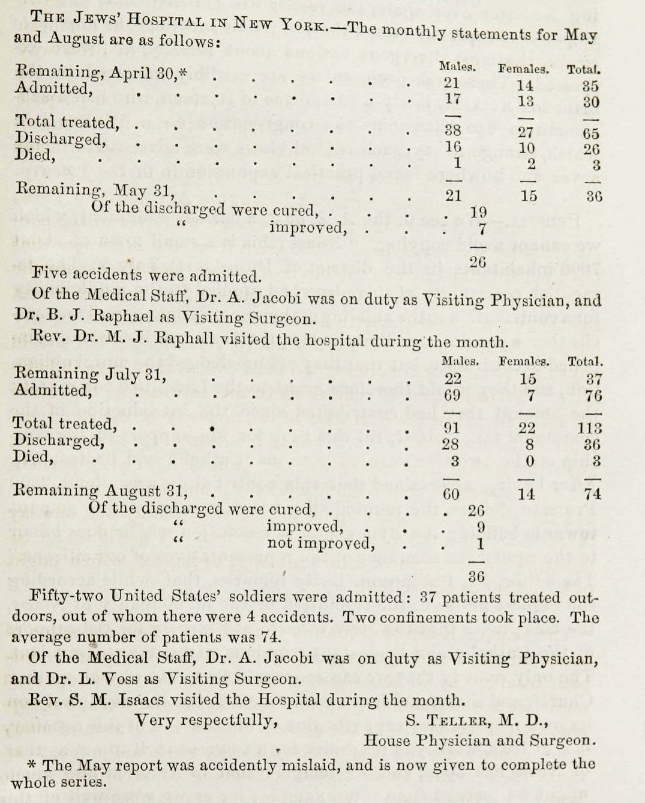

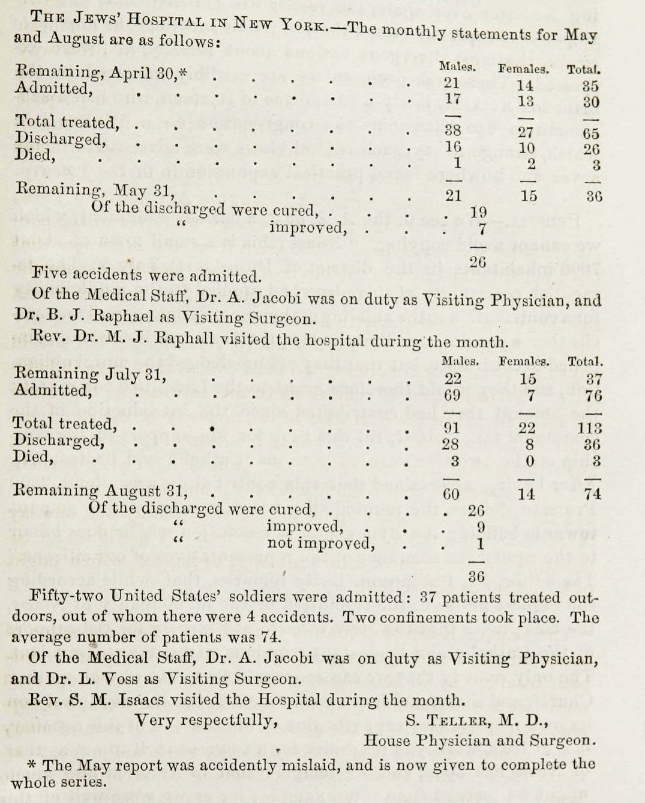

During the Civil War the Jews’ Hospital in New York was located on the south side of 28th Street between 6th and 7th Avenues and admitted on average 30 patients a month. In 1864 the staff consisted of three consulting surgeons, three attending surgeons, four attending physicians, “one resident physician and house surgeon, one superintendent, three nurses, three domestics, and one cook.” Annual reports state that from 1855 to 1860 the Hospital treated 1,285 people. However, during the war years, we are unable to say how many in total were admitted because we do not have annual reports for the years 1861, 1862, and 1863. However, Dr. Teller, House Physician and Surgeon, gave monthly reports on all but a few occasions to The Occident and American Jewish Advocate:

Dr. Teller either did not report the 1863 June and July statistics or the newspaper did not include them. But August, the month after the draft riots, the number of patients treated, 113, is higher than usual.

The Hospital underwent a great transformation during the Civil War. One of its three Attending Surgeons, Dr. Israel Moses, left to serve in the Union Army. Joseph Seligman, who had been on the Hospital’s Board since 1855 resigned his position in 1862 because of his “increasing responsibilities” frequently attending advisory meetings with President Lincoln. The most dramatic change was in 1861 when the Board of Directors resolved to establish a ward for injured Union soldiers, first totaling 48, then 69 beds.

The federal draft law was put into place in the summer of 1863, but it provided an exemption for people who could pay $300 or find someone to take their place. This infuriated the working class, the Irish and other recent immigrants, especially in New York, where Union loyalty was not a given. After the names had been drawn for the first round and published in the weekend’s papers, many New Yorkers were enraged. A large mob formed on the next day, and proceeded to attack and burn down the Provost Marshal’s building, where the draft was taking place. From there the mob moved all around the city, rioting, burning down entire buildings, injuring innocent bystanders, looting and committing outright murder. Described as “bitter street-to-street warfare”, the city was in chaos for four days.

Black people were the primary target of the mob’s atrocious violence due to racism and scapegoating, newspapers having created the narrative that enslaved people, once free, would take jobs from recent immigrants. Mobs lynched eleven Black men, hanging their mutilated bodies from lampposts. The total death count is unknown, but estimates range from over 100 to several hundred. The repercussions of the four days of extreme violence shape New York City even today. Because of the riots, it is estimated that nearly a thousand Black New Yorkers fled Manhattan en masse, seeking permanent refuge elsewhere, leaving behind their homes and communities. In their exodus from what was a racially integrated city, they settled in safer places, such as the historic Black community of Weeksville in Brooklyn (which was a city in its own right at the time). In the aftermath, New York became a more segregated city.

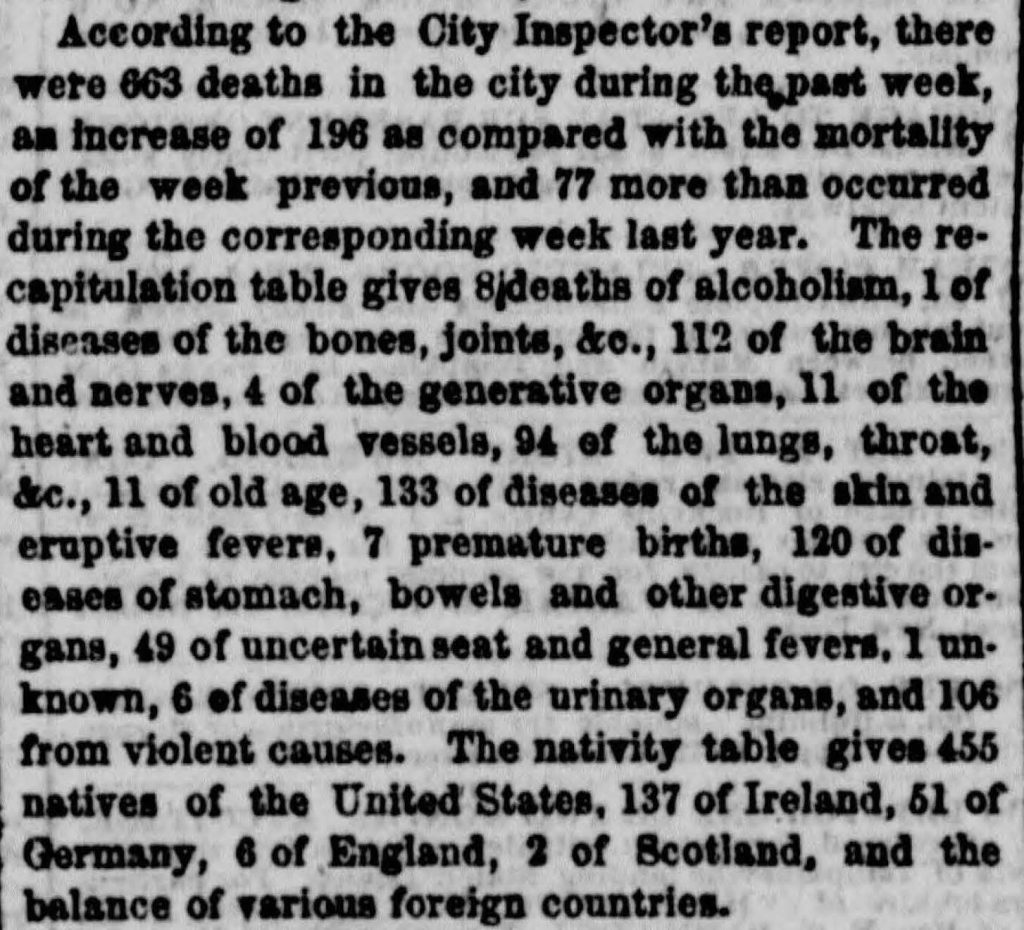

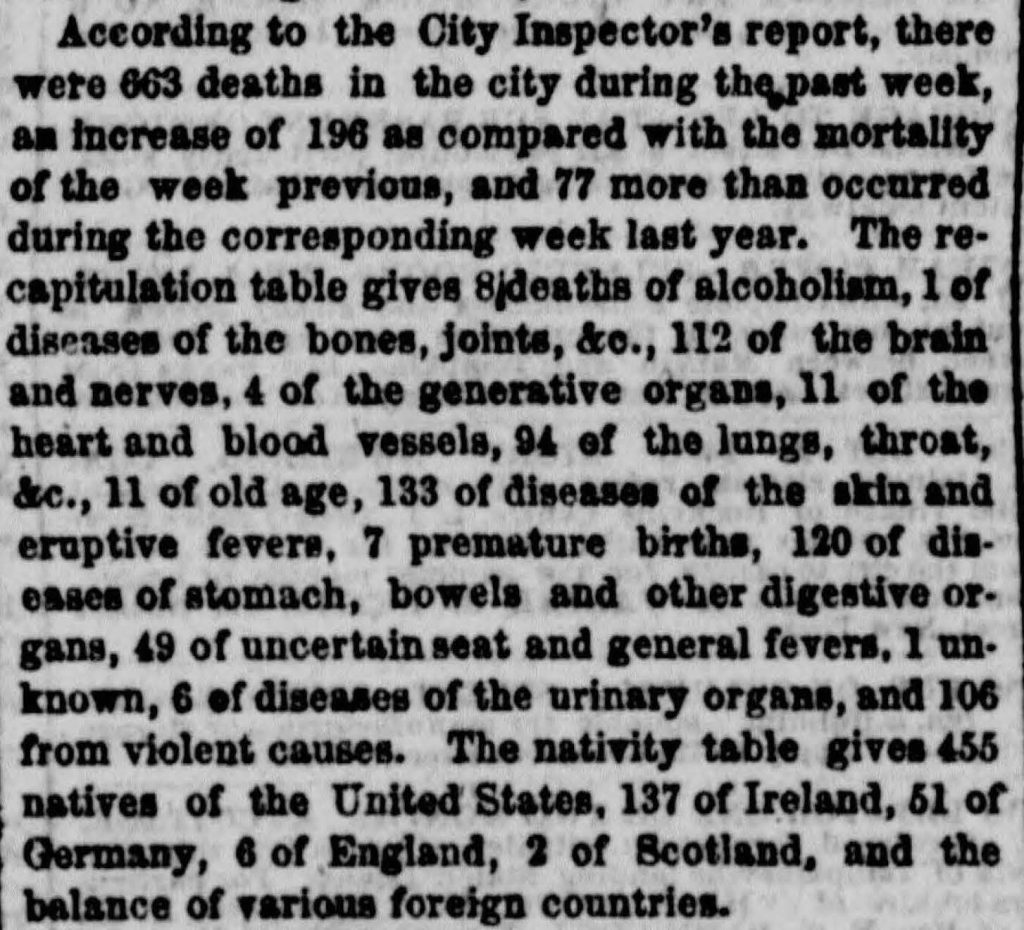

Excerpt from the July 21, 1863 edition of The New York Herald showing 106 deaths from violent causes, presumably the Draft Riots.

One early Mount Sinai doctor recalled:

In the early [1860’s] the hospital must have had its share of the casualties from the draft riots which occurred in the neighborhood, and of which I was in part an eyewitness: the burning of the colored Orphan Asylum in 40th Street, the attack on the Provost Marshall’s office on Broadway and 28th Street, the hanging of a [Black man] to a lamp post at 6th Avenue and 33rd Street, and the escape of frightened colored men, women, and children from the mob to the State Arsenal at 35th Street and Seventh Avenue under protection of a squad of soldiers.

Do we know how many people were treated at the Jews’ Hospital? While the Archives does not possess the case books from that era, we know that, “the geography of the rioting was such that Jews’ Hospital was frequently the center of its fury, and during the bloody days that ensued, it became the sanctuary of the sick and the wounded.” The newspapers of the time described multiple extremely violent events that took place only a few blocks from the Hospital. In all likelihood, the Hospital treated dozens of riot victims and the staff would witness the particular terror and brutal violence inflicted upon Black people.

In reading the minutes’ book entries of the subsequent months, there seems to be no end to the mundane issues the Board of Directors addressed. Rarely is there an explanation of motive or greater historical context included with a decision recorded in such matter of fact reports. However, in the months following the riots, the Hospital’s Board of Directors were:

Sensitive to their obligations to the country and the community during this period, the Board of Directors was also preparing the ground for the nonsectarian policy which has distinguished the Hospital ever since. Accident patients of all nationalities, races and religions had been accepted since the first day of the Hospital’s existence. But the national crisis crystallized the Board’s determination to rise above sectarianism and abolish it completely. In 1864, the Executive Committee had reported, “The Committee deem it proper to observe that many of those admitted to the Hospital were not of our faith, no distinction ever being made as to either the nationality or the religious belief of the sufferer.”

References

Albon P. Man. “Labor Competition and the New York Draft Riots of 1863.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 36, no. 4, 1951, pp. 375–405. https://doi.org/10.2307/2715371.

Hirsch, Joseph and Doherty, Beka. The First Hundred Years of the Mount Sinai Hospital of New York, 1852-1952. Random House: New York, 1952.

Jews’ Hospital in New York. Annual Report of the Directors of the Jews’ Hospital in New York, 1860. https://archive.org/details/annualreportofdi1860jews/page/18/mode/2up

Meyer, Alfred. “Recollections of Old Mount Sinai Days.” Journal of the Mount Sinai Hospital, vol. 3, no. 6, 1937, pp. 295-307.

Authored by J.E. Molly Seegers

Jan 31, 2022

Since the 2013 merger of the Continuum Health Partners into the Mount Sinai Health System, medical students working in the System’s hospitals have earned their MDs from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Newer staff and students may be unaware that prior to 2013, the Continuum Health Partners, made up of St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital, Beth Israel Medical Center and the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, now all a part of Mount Sinai’s System, played host to medical students attached to a different medical school. In fact, from very early days, Roosevelt Hospital and her sister institution, St. Luke’s Hospital, were associated with Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons (P&S), though Roosevelt’s ties are closer. How did this come to be exactly?

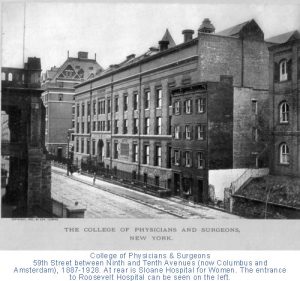

In 1885, P&S was located on East 23rd Street and Fourth Avenue, now known as Park Avenue South. William H. Vanderbilt, an American businessman and philanthropist, died in December of that year. He left a legacy of $300K and a plot of land on West 59th Street between Ninth and Tenth Avenues to P&S for the express purpose of building a new medical school, the largest donation to a medical school up to that time.

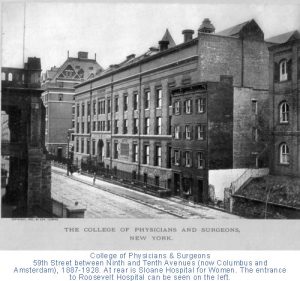

The College of Physicians and Surgeons on West 59th Street across from Roosevelt Hospital. You can see the Hospital’s Administrative Building port-cohere front column to the left in the image. (Photo source: Archives & Special Collections, Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

It just so happened that the Roosevelt Hospital, which had opened its doors several years earlier, was across the street from the new building. Of the twelve physicians chosen to be the first clinical staff of the Hospital, almost all of them were P&S alumni and held teaching positions there. It probably was no surprise to the staff to see medical students from P&S coming over to observe their professors’ clinics and surgeries.

By 1914, P&S students received bedside teaching on patient wards; by 1936, fourth-year students were allowed into the operating rooms. In 1928, the College of Physicians and Surgeons moved to the newly constructed medical center campus at 168 Street in Washington Heights, but their students continued to travel to clinical training at Roosevelt, and a number of other hospitals in the area.

Surprisingly, in over sixty years of P&S student training at Roosevelt Hospital, there was only a ‘handshake’ agreement between the medical school and the Hospital. However, by the late 1940s, there was discussion on the subject, and on October 24, 1951, the Board of Trustees put into place a formal affiliation with Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, allowing the students of the medical school to work at the hospital as part of their formal training. The agreement was signed by all parties on May 12, 1952. In 1971 it was renewed and expanded.

Medical studies aren’t the only tie between Columbia and Roosevelt Hospital, however. In 1964, an affiliation agreement between Columbia University’s School of Dental and Oral Surgery and Roosevelt Hospital was signed allowing dental students in to the surgery. That same year a two-year program in anesthesiology for the registered nurses was established at Roosevelt to help end the shortage of practitioners in this area. This program moved to Columbia University’s School of Nursing after the Roosevelt Hospital’s School of Nursing closed, and the loose ends of Roosevelt’s program merged with Columbia’s. The CRNA program – Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists – continues there to this day.

With the 2013 merger of St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center into the Mount Sinai Health System, ties to Columbia University’s programs may have come undone, but the history and influence of each institution upon the other remains, in the drive to produce outstanding medical professionals.

Jan 10, 2022

In a previous blog post, we looked at Beth Israel Hospital’s role in the 1918 Influenza Epidemic. Since then, we’ve done further research into the World War I correspondence in the Beth Israel records, as well as the Beth Israel Board of Directors and Committee minutes, which both provided rich details to supplement this history.

In early March 1918, influenza had reached New York. By March 25, 1918, an unknown correspondent (likely Louis J. Frank, Beth Israel Hospital superintendent) wrote that there was “quite an epidemic in the City of Grippe,” referring to New York City as literally the “City of the Flu”. As World War I continued on, many Beth Israel workers had joined the war effort, and their correspondence with the hospital describes the epidemic on the front lines. The first wave of the flu was relatively mild, and on May 13, 1918, Dr. Alfred A. Schwartz of the American Expeditionary Force, reported as much from France:

“I have been appointed Otolaryngologist to the contagious disease wards at the camp hospital and altho [sic] the title sounds like work, there must first be complications to the infectious diseases, and secondly…there must be some patients to have the diseases, and fortunately there is little to do.”

As the second, more deadly wave swept the world, the topic of influenza became more pressing in the correspondence, and was increasingly addressed in the Board minutes. In the November 17, 1918, minutes, the Board noted that back on the home front in New York, Beth Israel attended to “50 to 60 cases of Influenza a day during the height of the epidemic and…our records of cures was high, and our record of deaths was very low.” This is a significant deviation from the previous blog post, which stated that only twenty-nine patients total were treated during the epidemic at Beth Israel. Sources conflict on this point.

Staffing was amongst the most pressing issues at this time – with much of the medical staff overseas, Louis J. Frank, himself recovering from the flu, commented in a letter from October 23, 1918: “Our whole force is gone. If you were to come back today, you wouldn’t find a familiar face…From a house staff of 15 we have been reduced to a staff of five, and of the five, three have been laid up on account of influenza.” He goes on to describe the issue of hiring enough nurses, which was making him “frantic.” Superintendent Frank was a proponent of the conscription of women, “especially those women who have the vote,” to counteract staffing shortages in nursing in the war and at home.

The Board of Directors’ minutes reflect similar staffing concerns. The minutes for November 17, 1918, stated: “During the epidemic the Surgical Staff consisted of one man, the others became infected with the disease. On the Medical side we only had two men, the others also sick.” This appears to have resulted in redeployment of other clinical workers, and the Board resolved on “the discontinuance of the work of the Polio Department on account of the epidemic of Influenza and Pneumonia to release the doctors and nurses connected with the clinic for the more important work.” The minutes also noted that the “pupil nurses” from Beth Israel Training School for Nurses (today’s Phillips School of Nursing at MSBI) “after their day’s work was over, did extra work in the district on these cases, spending an hour or two on emergency cases requiring special care.”

The close of 1918 marked a turning point. With the War over, and a dwindling number of cases following the peak of the second wave, the end was in sight. In a letter from November 27, 1918, Superintendent Frank wrote:

“Things are getting into shape at the Hospital. We were considerably upset on account of the War, shortage of help, doctors, nurses, the Influenza epidemic, and the general anxiety, but with victory came a relaxation and we are now awaiting the homecoming of you men who have done so much to achieve this victory.”

The Board also noted, grimly, on November 17, 1918, that Beth Israel was “the only Hospital [in New York City] that didn’t lose a nurse, a doctor, or an employee by death.” On January 19, 1919, the Board moved to give House Staff and pupil nurses bonuses for their contributions and made especial note of the nurses’ service: “pupil nurses…after their trying [work and school] day of 12 and many times 14 hours, went out in the tenement houses and did extra work for several hours. Of course, this work was not for patients of the Hospital, but it was nevertheless our work, for they were the poor sick of our neighborhood.”

On November 23, 1919, the Board made note of the U.S. Public Health Service’s prediction that the influenza epidemic would return. Fortunately, this never came to pass. By 1920, the virus mutated to cause only ordinary cases of the seasonal flu, and the epidemic was effectively over.

Sources:

More resources on Mount Sinai Health System Hospitals and World War I are available here.

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Lillian Keturah Pond Farrar was born in Newton Center, Massachusetts in December 1871 to Jefferson Clinton Farrar Jr., and Sarah D. Pond. (2) She earned her BA at Boston University, and completed her medical education at the Cornell University Medical College. Records there indicate that prior to enrolling she took medical classes at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children between 1896 and 1899. She graduated from Cornell in 1900 at age 29, and returned to the New York Infirmary to take her internship. (3) After that, she spent several years (1901-1904) training in Paris and in Vienna, visiting medical clinics in Paris, Berlin, London, Stockholm, and Rome as well, much like any male physician of that time might do. (4)

Lillian Keturah Pond Farrar was born in Newton Center, Massachusetts in December 1871 to Jefferson Clinton Farrar Jr., and Sarah D. Pond. (2) She earned her BA at Boston University, and completed her medical education at the Cornell University Medical College. Records there indicate that prior to enrolling she took medical classes at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children between 1896 and 1899. She graduated from Cornell in 1900 at age 29, and returned to the New York Infirmary to take her internship. (3) After that, she spent several years (1901-1904) training in Paris and in Vienna, visiting medical clinics in Paris, Berlin, London, Stockholm, and Rome as well, much like any male physician of that time might do. (4)