Jan 10, 2022

In a previous blog post, we looked at Beth Israel Hospital’s role in the 1918 Influenza Epidemic. Since then, we’ve done further research into the World War I correspondence in the Beth Israel records, as well as the Beth Israel Board of Directors and Committee minutes, which both provided rich details to supplement this history.

In early March 1918, influenza had reached New York. By March 25, 1918, an unknown correspondent (likely Louis J. Frank, Beth Israel Hospital superintendent) wrote that there was “quite an epidemic in the City of Grippe,” referring to New York City as literally the “City of the Flu”. As World War I continued on, many Beth Israel workers had joined the war effort, and their correspondence with the hospital describes the epidemic on the front lines. The first wave of the flu was relatively mild, and on May 13, 1918, Dr. Alfred A. Schwartz of the American Expeditionary Force, reported as much from France:

“I have been appointed Otolaryngologist to the contagious disease wards at the camp hospital and altho [sic] the title sounds like work, there must first be complications to the infectious diseases, and secondly…there must be some patients to have the diseases, and fortunately there is little to do.”

As the second, more deadly wave swept the world, the topic of influenza became more pressing in the correspondence, and was increasingly addressed in the Board minutes. In the November 17, 1918, minutes, the Board noted that back on the home front in New York, Beth Israel attended to “50 to 60 cases of Influenza a day during the height of the epidemic and…our records of cures was high, and our record of deaths was very low.” This is a significant deviation from the previous blog post, which stated that only twenty-nine patients total were treated during the epidemic at Beth Israel. Sources conflict on this point.

Staffing was amongst the most pressing issues at this time – with much of the medical staff overseas, Louis J. Frank, himself recovering from the flu, commented in a letter from October 23, 1918: “Our whole force is gone. If you were to come back today, you wouldn’t find a familiar face…From a house staff of 15 we have been reduced to a staff of five, and of the five, three have been laid up on account of influenza.” He goes on to describe the issue of hiring enough nurses, which was making him “frantic.” Superintendent Frank was a proponent of the conscription of women, “especially those women who have the vote,” to counteract staffing shortages in nursing in the war and at home.

The Board of Directors’ minutes reflect similar staffing concerns. The minutes for November 17, 1918, stated: “During the epidemic the Surgical Staff consisted of one man, the others became infected with the disease. On the Medical side we only had two men, the others also sick.” This appears to have resulted in redeployment of other clinical workers, and the Board resolved on “the discontinuance of the work of the Polio Department on account of the epidemic of Influenza and Pneumonia to release the doctors and nurses connected with the clinic for the more important work.” The minutes also noted that the “pupil nurses” from Beth Israel Training School for Nurses (today’s Phillips School of Nursing at MSBI) “after their day’s work was over, did extra work in the district on these cases, spending an hour or two on emergency cases requiring special care.”

The close of 1918 marked a turning point. With the War over, and a dwindling number of cases following the peak of the second wave, the end was in sight. In a letter from November 27, 1918, Superintendent Frank wrote:

“Things are getting into shape at the Hospital. We were considerably upset on account of the War, shortage of help, doctors, nurses, the Influenza epidemic, and the general anxiety, but with victory came a relaxation and we are now awaiting the homecoming of you men who have done so much to achieve this victory.”

The Board also noted, grimly, on November 17, 1918, that Beth Israel was “the only Hospital [in New York City] that didn’t lose a nurse, a doctor, or an employee by death.” On January 19, 1919, the Board moved to give House Staff and pupil nurses bonuses for their contributions and made especial note of the nurses’ service: “pupil nurses…after their trying [work and school] day of 12 and many times 14 hours, went out in the tenement houses and did extra work for several hours. Of course, this work was not for patients of the Hospital, but it was nevertheless our work, for they were the poor sick of our neighborhood.”

On November 23, 1919, the Board made note of the U.S. Public Health Service’s prediction that the influenza epidemic would return. Fortunately, this never came to pass. By 1920, the virus mutated to cause only ordinary cases of the seasonal flu, and the epidemic was effectively over.

Sources:

More resources on Mount Sinai Health System Hospitals and World War I are available here.

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Oct 12, 2021

See Building Beth Israel, Part 1: Foundations and Part 2: Jefferson and Cherry for the first parts of this series. An interactive map of Beth Israel historical locations is available here.

The final years at Beth Israel Hospital’s Jefferson and Cherry Streets location were marked by some of the most defining moments of the early twentieth century. While it’s not clear exactly when conversations in favor of a new hospital began, the Beth Israel Board of Directors began to purchase property on Livingston Place along Stuyvesant Square Park as early as 1915. (Livingston Place would later be renamed Nathan D. Perlman Place after the U.S. Congressman and Beth Israel Vice President.)

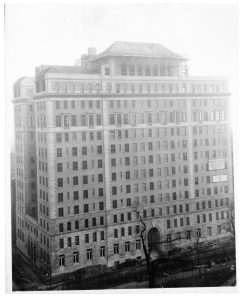

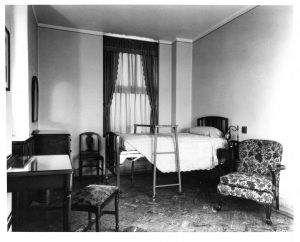

A primary motivation for the creation of what would become the Dazian Pavillion was likely related to hospital capacity – the thirteen-story building opened with nearly 500 private rooms and state-of-the-art facilities, a significant expansion over the 134 beds in wards at the Jefferson and Cherry Streets location. That said, justifications for the new building from the Board of Directors evolved from its earliest phases and its final construction in 1929. These reflect the many historical events of the era: modernization of health care, the introduction of the skyscraper, World War I and its aftermath, mass immigration, and the Influenza Epidemic of 1918.

The Tallest Hospital Building in the World

The Dazian Pavillion was conceived as a highly modern, state-of-the-art hospital building. At thirteen stories, it was the tallest hospital building in the world at that time. According to Islands of Compassion, Beth Israel “was the first to realize that a hospital skyscraper would mean freedom from the city’s noise and congestion.” This is evident in the discussions in the Board of Directors minutes. From March 16th, 1919:

It is of great concern to us to construct the new hospital according to the best methods of building; to provide the patients with as much comfort as possible, to serve them with palatable food, to provide them with fresh air and sunshine, to guard them from undue noise and excitement, and to keep the patient away from the smell and the workings of the Hospital – in a word, we are studying how best to care for the patient…The hospital of the future must be organized for prevention and not so much for cure.

World War I and its Aftermath

World War I was strongly felt at Beth Israel Hospital, with nearly half of the medical staff enlisted in the war effort. This continued throughout the war and beyond its end, and care for veterans presented itself as an early justification for a new hospital building. From the November 18, 1917 Board of Directors minutes:

The War presents the strongest argument for the construction of the new building. The War will last for some time and it is absolutely certain that there will be a great demand for hospital accommodation especially on account of the draft; deformities and disabilities are being discovered which require doctoring and good hospital care. The Beth Israel Hospital will be the only institution in the City to come up to expectations. We must be ready to receive cases on account of the epidemic that will surely follow the War and the new Hospital should stand as a permanent monument.

Beth Israel’s service to those affected by the war did not end with veterans. From the Board of Directors Minutes, October 17, 1920:

Congressman Siegel informed me that there are 200,000 Jews trying to secure passports for the United States. Orthodox Jews from Syria and Greece will come here in large numbers. That there are 15,000 Jews at Danzig awaiting transportation. If there is any doubt at all in the minds of anyone as to the necessity of a 500 bed Beth Israel Hospital for the treatment of Orthodox Jews this statement of Congressman Siegel should dispel them.

If Beth Israel was founded to care for Jewish immigrants in New York, the events following World War I only strengthened this resolve.

Influenza Pandemic of 1918

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918 was also a justification for the layout of the new building. The need for private rooms was a strong topic of debate in the years leading up to construction, within both the Board of Directors and the medical profession, considering hospitals largely operated out of shared wards at this time. The pandemic cemented the need for private rooms. From the Board of Directors Minutes, November 23, 1919:

…in respiratory infections…protection can only be obtained by safe-guarding one person from another, that the lesson derived from the severe experience of the recent Pneumonia epidemic is to the effect that such patients are not to be assembled into larged [sic] groups or kept in open wards but should be kept in separate rooms where they and their attendants may be preserved as far as possible from sputum droplet contamination.

The Dazian building would come to feature almost entirely private rooms.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the Dazian Pavillion took more than a decade to come to fruition. While many of the buildings and lots for the future space were purchased throughout the 1910s, there was significant slowdown in building progress due to the influenza epidemic. Building materials were also more expensive due to World War I.

On November 5, 1922 the cornerstone was laid. The ground was broken by Isaac Phillips, and future President Herbert Hoover, then U.S. Secretary of Commerce, were in attendance. The architect for the Dazian building was Louis Allen Abramson.

The building was finally opened in 1929. The Beth Israel Hospital School of Nursing (today the Phillips School of Nursing at Mount Sinai Beth Israel) moved into the 6th and 9th floors. Nearly 100 years after construction began, Dazian continues to be the home of Mount Sinai Beth Israel today.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Sep 28, 2021

See Building Beth Israel, Part 1: Foundations for the first part of this series. An interactive map of Beth Israel historical locations is available here. More archival material about the Jefferson and Cherry Streets location is here.

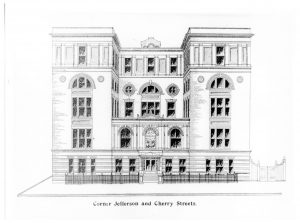

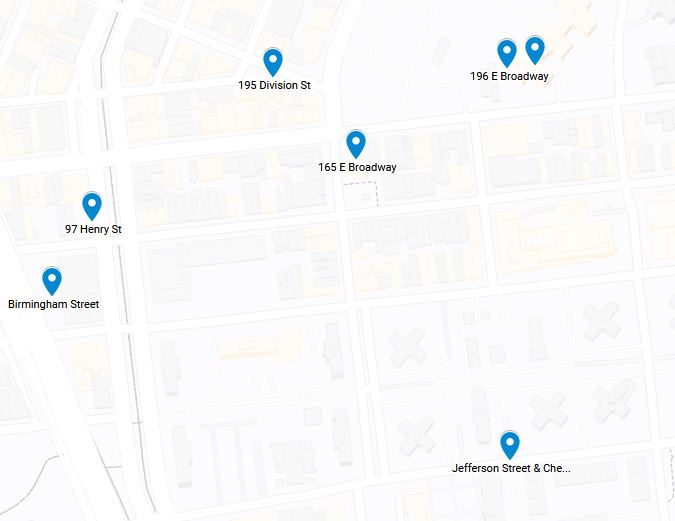

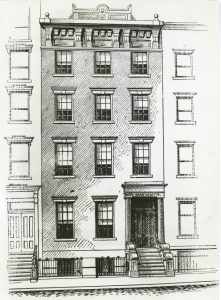

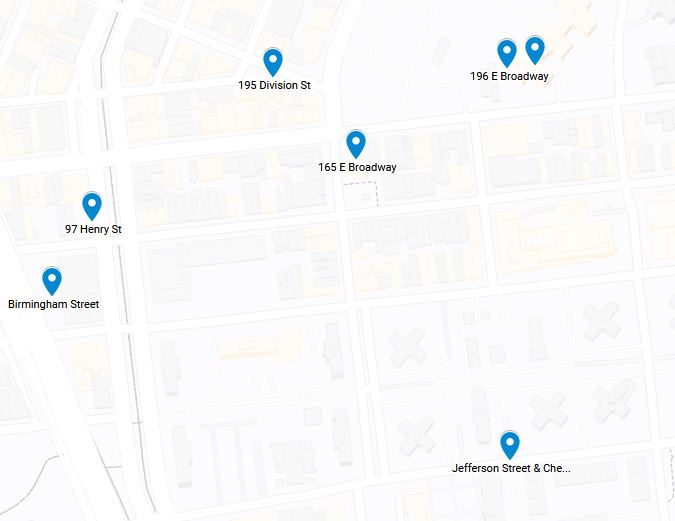

For much of the 1890s, the first decade of its existence, the location of Beth Israel Hospital was a moving target. The hospital moved from a factory loft, to an “old-fashioned parlor floor,” to two different rented hospital facilities. In its final locations during this period, split between buildings at 206 East Broadway and 195 Division Street, Beth Israel Hospital was financially solvent for the first time, enabling it to finally buy land of its own. In 1896, Beth Israel purchased a plot of land at Jefferson and Cherry Streets for the construction of a new hospital building.

In 1899, the Beth Israel Board of Directors chose a design for the new hospital. The cornerstone of the building was laid on April 1, 1900.

Much of the early funding for the new location was put up by Beth Israel’s Board of Directors, which, in addition to a mortgage, allowed for the purchase of the lot. However, the cost for the chosen design was well above initial expectations, and the final estimate was around $200,000 (about $6.5 million in 2021 dollars), requiring a significant fundraising effort.

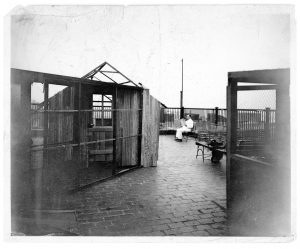

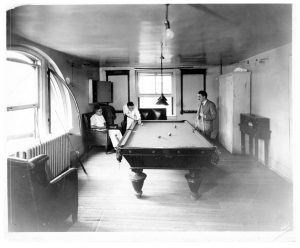

On May 26, 1902, the new Beth Israel Hospital at Jefferson and Cherry Streets was dedicated. It included 134 beds, with male, female, and maternity wards as well as private rooms. It featured a solarium, a common feature for hospitals at that time, in addition to outdoor space on the roof for staff and patient use. The Beth Israel Hospital Training School for Nurses was founded in 1904 and moved into this building. (Today, it is the Phillips School of Nursing at Mount Sinai Beth Israel.)

By August 1912, a physiological chemistry laboratory opened at Beth Israel under the direction of Max Kahn, PhD. The laboratory was located on the top floor and could comfortably hold five people. Additionally, after extensive delays, a children’s ward opened in January 1919, but it was forced to close six months later because of the nursing shortage caused by the Influenza Epidemic of 1918. Both the children’s and maternity wards were closed and re-opened periodically, based on available financial and staff support.

As early as 1915, the Beth Israel Board of Directors began to purchase property on Livingston Place along Stuyvesant Square Park. Plans to move to this new location were delayed first by World War I, and then by the influenza epidemic. Construction began in earnest in 1922, and Beth Israel finally moved to its current location in the Dazian Pavillion in 1929, giving up the Jefferson and Cherry Streets location. While it wasn’t the Hospital’s final location, Jefferson and Cherry Streets is where Beth Israel Hospital came of age and began to resemble the hospital of today.

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Aug 31, 2021

The first meeting related to the founding of Beth Israel Hospital was held on December 1, 1889 at 165 East Broadway. Healthcare was greatly needed in New York’s Lower East Side, whose residents, largely recent Jewish immigrants, were affected by poverty, close living quarters, and dangerous working conditions. From a 1901 essay on early Beth Israel history:

“The origin of the idea of this institution sprang from the poor themselves. So urgent was the need for such a local hospital, that in spite of the lack of support, and even of the discouragement of those in position to assume such a task, the poor themselves, by taxing their hard earned [sic] wages, gained by the sweat of their brows, established the association and undertook to support the Hospital…It serves to demonstrate the noble Jewish heart. These workingmen when they could earn their bread and butter were willing to contribute their 25 cents a month to help their neighbors in distress.”

In the face of “meagre [sic] and uncertain support,” the founders first endeavored to begin a dispensary, rather than a full-scale hospital, and in May 1890, rented a loft in a factory on Birmingham Street. (This street no longer exists, but today would be between Henry Street and Madison Street, just underneath the Manhattan Bridge.) The building was described as “most unsuitable and the accommodations about as poor as can be imagined” but still attracted more patients than could be treated, speaking to the great need for medical care in this neighborhood at the time.

Click here for an interactive map of Beth Israel historical locations

After two months at the Birmingham Street location, the Beth Israel outpatient dispensary moved to 97 Henry Street in July 1890. Described as an “old-fashioned parlor floor,” it was “much better situated” and the dispensary remained there for ten months.

Sketch of the 206 E Broadway location of Beth Israel Hospital, circa 1892-1902.

In May 1891, Beth Israel moved to 196 East Broadway. With twenty beds, this is the first Beth Israel location to include inpatient services in addition to the outpatient dispensary. The hospital includes two house staff: Abraham Hymanson, MD, is the first House Physician, and Wolfgang Kaplan, MD is Assistant House Physician.

Embroiled in a financial crisis, Beth Israel moves again in May 1892, splitting their services across buildings at 206 East Broadway and 195 Division Street. With lower rent and more space, including thirty-four beds, Beth Israel was financially solvent for the first time. The Division Street building was renovated one floor at a time for inpatient and outpatient use.

Beth Israel Hospital remained in this location for over a decade, before moving to its location at Jefferson and Cherry Streets in 1902, and finally its current location at the Dazian Pavillion in Stuyvesant Square in 1929. The history of both of these Beth Israel Hospital locations will be addressed in future posts.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist

Jun 4, 2020

An update to this blog post can be found here.

Founded in 1892, the early history of Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital was decorated with a series of success stories in the treatment of disease. Against the background of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, then affected by poverty, close living quarters, and dangerous working conditions, its residents, largely recent Jewish immigrants, were made vulnerable to many of the contagious diseases of that era. In its first years, Beth Israel contributed research to combat the typhoid epidemic of 1906-1907, established an after-care clinic to children affected by the 1916 polio epidemic, and is credited with finding the cure for trachoma, which had previously been a cause to turn away new immigrants at Ellis Island.

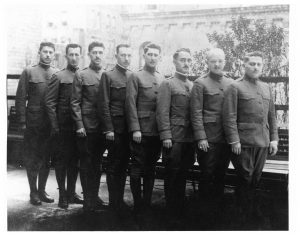

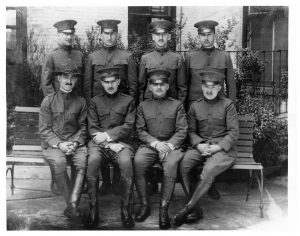

Only twenty-five years after Beth Israel’s opening, the United States was embroiled in the first World War. The Hospital encouraged its medical staff to join the Medical Reserve Corps, with approximately half of its doctors signing up. The Hospital had also encouraged its nurses, physicians and other staff to join the war effort.

This left Beth Israel in a precarious position when the 1918 Influenza epidemic reached New York City. Being chronically understaffed, Beth Israel’s Medical Board contacted the Department of Health for advice. The response was simply: “There is nothing to advise except the use of gauze masks which did not always prevent the disease.” In November 1918, the Hospital eliminated visiting hours, curtailed teaching hours, and turned the Male Medical Ward over to the Department of Health to use as an isolation facility for the pandemic. (The DOH never used the facility because they were similarly understaffed.)

Female ward of Beth Israel Hospital, Jefferson and Cherry Street, circa 1910

Ultimately, Beth Israel was only able to admit twenty-nine influenza patients. (Update: This number is disputed in other sources.) Seven members of the House Staff were awarded $25 (approximately $500 today) for “self-sacrificing services performed” and the Hospital offered special incentive pay to doctors and nurses to help combat the fact that they were understaffed.

Despite the limited patient intake, Beth Israel’s contributions to the 1918 flu pandemic were still impactful. In December 1918, Superintendent of the Hospital, Louis J. Frank, contacted Presidents Roosevelt and Taft to encourage universal nursing training in the education of women, likely in response to the chronic under-staffing at this time. By January 1919, many of the patients in the Hospital were admitted for “post-influenzal complications” leading to the care of many affected by the pandemic.

Sources:

Authored by Stefana Breitwieser, Digital Archivist